Sabantuy (Сабантуй) is the traditional Volga (Kazan) Tatar summer festival. It dates back to pre-Islamic, pagan times and originally was a ritual that asked the gods for a plentiful harvest. Today, however, the festival can best be understood as a national Tatar celebration of their culture and traditions.

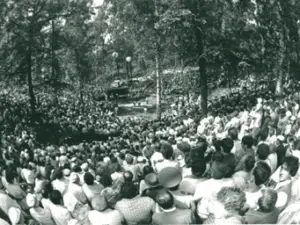

Sabantuy are inclusive, community-building events. In Tatarstan, villages will host smaller celebrations, followed by larger regional centers, followed a grand final celebration in Kazan, the capital. This creates a festive travel season in which relatives and old friends find reason to visit each other and new connections can be made.

Further, other Turkic groups in Russia have similar festivals. The Bashkir, for instance, have a festival named Habantuy (Һабантуй) and the Chuvash have Akatuy (Акатуй). It is common to find booths and stalls at Sabantuy and other Turkic celebrations that present each other’s cultures as well. Likewise, celebrations welcome all attendees. In major cities with a large Turkic diaspora, there is often one large celebration organized and attended by all.

Origins and History of Sabantuy

The name Sabantuy has Turkic roots and can be translated as “Festival of the Plow.” The name Sabantuy is made up of two parts: “saban” (сабан) which means “plow” and “tuy” (туй) which means “festival” (or “wedding”).

Sabantuy dates back to well over a thousand years ago and has pagan roots. Prior to the Volga Bolgars accepting Islam in the 10th century, the festival had a religious purpose and was celebrated prior to the sowing of crops in hopes of bringing about a successful harvest.

Many of Sabantuy’s traditions, however, likely came from those developed over the Tatars’ much longer history as a nomadic people before they settled into the powerful kingdom of Volga Bulgaria. Indeed, there are other, similar traditions still practiced by other Eurasian peoples who share a similar Turko-Monologian Tengrian heritage, such the Sakha, whose Yhyakh festival also shares some traditions with Sabantuy.

The first written account of Sabantuy was by the Arab Muslim traveler Ahmad ibn Fadlan in 921-922. The Volga Bolgars had recently converted to Islam at the time and thus Fadlan arrived to document their current customs.

After the conversion to Islam, the festival gradually lost its pagan religious significance and, during the Soviet period, the date of celebration was moved from before the sowing of crops to after the sowing and before the harvest.

The several ethnographic records of the celebration of Sabantuy made since the 10th century show that the celebration in the many regions in which Tatars lived was far from identical. Only in the 20th century would Sabantuy begin to be understood as a unified Tatar celebration, resulting in some, such as the Siberian Tatars, beginning to celebrate Sabantuy for the first time. During this period the multi-stage custom of celebration came about with first the small individual Tatar villages celebrating Sabantuy, then the larger regional cities in Tatarstan, and finally Tatarstan’s capital city, Kazan, celebrating to top off the festival.

While this festival has no set day or month, it tends to take place after the sowing of crops, so generally in late May or June.

In the early 20th century as well, Sabantuy began being celebrated outside of the traditional homelands of the Tatars in major Russian cities like Moscow and Saint Petersburg as the Tatar diaspora in these cities grew. Today, festivals can be found as far afield as London and New York. For diaspora communities, the festival has taken on a new meaning as it helped these Tatars far from their homeland to hold on to and celebrate their culture. If you are looking to potentially attend the celebrations, note that dates outside of Russia can vary particularly widely.

Sabantuy Games, Competitions, and Preparations

Especially in smaller villages, the celebration can take place over several days as the preparation for the festival is considered part of the celebration as well. These preparations are highly diverse. In some places, children collect and paint eggs. These can be used as prizes in competitions or might be sold to help fund the festivities.

In other places, rituals include offering others a kasha (кашa) known as karga botkasi (карга боткасы) or zere botkasi (зэрэ боткасы). This ritual of preparing the kasha, involves a village collectively preparing porridge with each household contributing some grain.

In many places, preparation also includes gathering prizes, which are often fabrics with intricate needlework. Needlework made by women who were married within a year prior to Sabanatuy are particularly valued.

The part of Sabantuy which takes place on the maidan (a word that refers to a public square or place) is defined by boisterous games and competitions.

The horse races are almost always held first. Tatars have been historically known for their horsemanship and continue to highly prize horses, so horse races mark most Tatar celebrations. In villages, young boys from the age of 8 to 12 participate in the horse races for Sabantuy. The competitors (and there tend to be many) leave the village and go several miles down the road to the start line. They then race from that point back to the village where the villagers await to celebrate the victor. The winner of the race is awarded the best embroidered fabric and celebrated as a local hero.

The competitions and games have been varied and many that were not initially part of Sabantuy later were incorporated into the festivities during the 19th and 20th centuries. Some of what are understood to be original competitions include foot races, jumping competitions, archery, and arm wrestling.

Other competitions and games which are considered to be traditionally Tatar arguably came to Sabantuy from Russian fairs. These include bean bag races, racing with an egg on a spoon, walking on a swinging, loosely-tied beam, racing while carrying a yoke and two buckets of water, climbing a wooden pole (a prize is often hung on top), three-legged races, tug-of-war, trying to break a pot on the ground with a stick while blindfolded, and hitting each other with sacks while balancing on a beam.

The latter two competitions are particularly enduring and popular as they provide for many comic scenes. The first sees the competitor blindfolded, handed a stick, and led 10-12 steps away from a clay pot, and turned 180 degrees around. The competitor then attempts to break the clay pot with the stick and those who are able to win a prize. The second is a glorified and complicated pillow fight of sorts. Two competitors sit on a beam that is several feet off the ground (high enough that their feet won’t touch the ground) and are handed sacks or pillowcases filled with hay. The competitors then hit each other with the sacks of hay, simultaneously trying to knock their opponent off the beam while not falling off themselves. Another popular game is to try to find a coin in a bowl of qatiq (катык), a fermented milk product, without using one’s hands.

By far, the most popular (and considered the mostly ethnically Tatar) of the competitions remains the traditional style of wrestling, kuresh (tat. көрәш, rus. куреш). When and how kuresh originated is uncertain, but it remains a sport popular among most Turko-Mongolian cultures.

Wrestling itself is an ancient sport and training discipline used to prepare fighters for war. Within the Mongol-Turkic nomadic groups, wrestling was connected to prized traits such as courage, strength, and masculinity. The more traditional competitions such as kuresh and horse racing were generally limited to male participants, while the modern games and competitions would see both men and women compete. Among Tatars, kuresh is usually associated with celebrations such as Sabantuy and only recently, in the past century, has become more official with regional, state, and world championships in kuresh being held since the Soviet era.

While there are many individual styles of wrestling among these cultures, Tatar kuresh distinguishes itself in its use of a towel or a length of fabric. Competitors face each other with a piece of fabric loosely wrapped around each of their waists. Holding on to the fabric, each competitor tries to throw their opponent to the ground so that their shoulder blades touch the mat. Depending on the age of the competitor, a round lasts between 2 to 4 minutes. In Sabantuy, the competitions usually start with the youngest competitors (but occasionally the oldest) and do rounds based on age and/or weight groups. The most exciting part would be when two undefeated wrestlers face each other in a final round. The winner of this round is proclaimed the strongest batyr (tat. батыр), a Turkic word meaning “warrior,” of the Sabantuy and traditionally is awarded a ram which he then often hoists to his shoulders in another show of strength. In more recent years, particularly in the cities where one would find little use for a live ram, prizes have been different and included expensive items like cars.

Music and Dance in Sabantuy

Music and dance are a big part of any celebration and Sabantuy is no different, with traditional Tatar music and dance featured throughout. Traditional Tatar music comes in several forms with some more fast-paced songs for dancing, while others are slower for sing-alongs or religious purposes. Tatar music often uses traditional instruments such as the Tatar/Bashkir flute, known as a quray (курай). The Russian bayan, a type of accordion, can also be expected to be featured prominently at Sabantuy.

Large Sabantuy festivals will today feature professional singers and artists. These performances may be of traditional songs that most in the audience would recognize or even modern Tatar music that incorporates more Western instruments and motifs.

Dance is performed by troupes of both children and adults. The dances one may see at Sabantuy contain both elements of modern urban and traditional rural dances. As dancing developed among Tatars as a form of art, dance troupes were established and dances choreographed with elements pulled from traditional Tatar dances as well as Russian and other Eastern styles. Originally performers would dance solo although now more group dances are popular. Often dances were created to fit specific traditional songs or vice versa.

In villages, dances reflected labor and military activities and expressed the qualities important to Tatars. In these dances, men and women have different movements. Male dancers are active and supposed to show courage and masculinity; male dancers move their hands freely and perform quick jumps and turns. Female dancers were expected to show more modesty with an emphasis on the hands of the female moving from either her apron or her scarf, therefore almost protecting an almost “forbidden zone.”

The impact of village life and duties on dance can be seen in the popular traditional song and dance “The Goose Feather” or kaz kanaty (tat. каз канаты, rus. гусиное перо). This dance, in which the hands replicate the movement of birds, was developed based on the eponymous song kaz kanaty. The song came from folk songs sung during the annual plucking of geese in the fall and developed from there.

Tatar performers often visit cities where there is a significant diaspora. In Saint Petersburg, for example, there have been three performance stages: one stage for local Tatar performers from the Saint Petersburg area; the second stage for performers from Bashkortostan (in Saint Petersburg the Tatar Sabantuy and Bashkir Habantuy are celebrated together); and the final stage is for performers from Tatarstan.

Matchmaking at Sabantuy

In addition to the merrymaking, Sabantuy is also important for those looking to find love. Meeting one’s partner during Sabantuy has been traditionally considered to be a good omen and those married during Sabantuy have been believed to have the strongest marriages.

In diaspora communities, Sabantuy has been crucial in bringing about marriages. Many ethnic minorities in Russia emphasize marrying someone from your own ethnic group in order to have cultural and religious continuity. While times have changed and people have become more accepting of interethnic marriages, Sabantuy remains a great opportunity for many young Tatar men and women in diaspora communities to meet and spend time with people from a similar cultural background.

Tatar Traditional Clothing

In the past, everyone might have been wearing traditional Tatar clothes. However, now as most Tatars wear modern, Western clothing, Sabantuy is a time when many people, performers, and ordinary visitors, choose to dress in at least some elements of traditional clothing. The undoubtedly most popular and extensively worn element is the tubeteika (tat. түбәтәй, rus. тюбетейка). The tubeteika is a traditional, ornate skullcap worn by Tatar and Bashkir men and women. Similar caps are popular in Central Asian cultures under various names and in other Muslim regions of the former Soviet Union. These tubeteikas tend to differ in shape, design, color, and material by region. Tatar tubeteikas, even those worn by men, tend to be of a velvety material and sewn over with patterns of silky threads and beading.

While many Tatar women wear the tubeteika as well, the traditional headpiece for women is the kalfak (калфак). The kalfak is almost like a stocking hat and, like the tubeteika, made of a velvety material and ornately decorated with patterns embroidered in silky threads. The kalfak is specific to Tatar female dress and continues to be worn to show belonging to the Tatar community and national pride. The kalfak can also be worn in different ways. Some choose to wear it under a scarf or shawl, while others wear it on its own as a cap.

Tatar Traditional Food and Drink

No celebration would be complete without food. As with other elements of Sabantuy, one can find a mix of traditional Tatar recipes as well as imported favorites. While many families may bring their own food, even in small villages, Sabantuy is a good excuse to indulge in the Tatar treats which may be sold there.

Playing a very special role is a particular pride for Tatars, a sweet treat called chak-chak (tat. чәк-чәк, rus. чак-чак) is king. This dessert of fried dough pieces held together with honey is one usually eaten at special celebrations, so it is not surprising to see chak-chak at a Sabantuy. Frequently, chak-chak plays a role in the communal aspect of Sabantuy as it is a treat that can easily be made in large quantities and formed into decorative presentations (in Nizhny Novgorod in 2016, approximately 440 pounds or 200 kilograms of chak-chak was made for Sabantuy) and offered to visitors.

In many villages a type of fragrant, mint-flavored cookie, kyzyl bille (кызыл билле), was especially popular alongside other sweet treats. The Tatar kitchen has numerous unique recipes for baked goods and sweets that may be simple with just a honey or sugar coating or may contain meat, vegetables, fruits, or other fillings. An example of such a pie would be gubadia (tat. гөбəдия, rus. губадия). Gubadia is multi-layer pie that is traditionally served only at special occasions usually with tea. Some popular fillings include rice, raisins, eggs, meat, dried apricots, prunes, and kurt (tat. корт, rus. курут) a product made from dried fermented milk.

Another popular Tatar food is the triangle-shaped echpochmak meat pie (tat. өчпочмак, rus. эчпочмак/треугольник) and treats like horse-meat sausage (Rus. конская колбаса), called qazylyk (казылык) or simply qazy (казы). Both echpochmak and qazy speak to the nomadic roots of Tatars and the importance of horses. Back when Tatars were still nomadic, echpochmak was popular as it was an easy dish to cook and would not require a long rest break. If closed, they also traveled quite well. Echpochmak also can contain horse meat, although it usually is made with lamb or beef.

The food options are not limited to Tatar food. Sabantuy may also have food like Uzbek pilaf or plov (tat. пылау, rus. плов) and Caucasian shashlik (shish kabab) or European candies for the children, and more.

Popular Tatar drinks vary but are similar in their emphasis on milk. A drink specific to Tatars and other Turkic groups is kumis (tat. кымыз, rus. кумыс), a fermented mare’s milk drink believed to have healing qualities. Ayran (tat. әйрән, rus. айран) is another popular drink; it is made from yogurt and water. Lastly there is the previously mentioned qatiq, a thicker drink which plays a special role as a part of the games of Sabantuy.

Personal Experiences with Sabantuy

As someone with Tatar heritage but who grew up outside of Tatarstan, Sabantuy was my first brush with Tatar culture. In my childhood, my family went several times to the Sabantuy held in the Bay Area by the Tatar diaspora in California. It seemed to me even then to be a celebration oriented towards children with games, sweets, and prizes. For the older generation, however, Sabantuy meant so much more.

For my grandparents, as part of the Tatar diaspora in Saint Petersburg, Sabantuy was an opportunity to celebrate their culture, to speak their native language in a city in which they were otherwise inundated by Russian language and culture. In the 1970s, when my grandparents began going, the celebration was very informal with Tatars gathering at a location in the countryside outside of Saint Petersburg with shared food and music. For my mother and her aunt, Sabantuy was the event to which their parents dragged them as their mother implored them to find a nice Tatar malay (tat. малай), a boy.

I had the opportunity to attend Sabantuy in Saint Petersburg in 2019. It was wildly different from what I had experienced in California or heard about from my grandparents both in scale and content. The performers were professional and on-stage, a change from the sing-alongs my grandparents told me about. There were thousands of people, many of whom were not even ethnically Tatar.

The Tatar food, which was such a big part of my childhood recollections of Sabantuy, was largely on show for the thousands of visitors and not for sale. What had been a celebration of Tatar culture by Tatars and for Tatars had become a display of that same culture by Tatars for everyone. This change had made the festival more accessible to others and universal, allowing everyone from Tatars to Russians, Central Asians, and people from the Caucasus to enjoy a day in the fresh air and revel in spirit of Sabantuy.

In 2022, I again attended Sabantuy in California. After two years of COVID-19 cancellations, the Tatars of Northern California were finally able to meet and celebrate together again. As someone who had gone to Sabantuy several times as a child, it was an opportunity to see familiar faces as well as meet new people who had come to the USA more recently. In many ways the event was more joyous as after two years of lockdowns and COVID restrictions, people were finally able to catch up in-person in their native language. In childhood, my interests had centered around the Tatar food and the traditional games we would play, but this time, as though for the first time, I noticed the diversity among the Tatars who came. While there were the usual Tatars from Kazan and Tatarstan, there were also many from other parts of Russia such as Bashkortostan and even Central Asian countries.

I also personally found it an interesting linguistic experience. For somebody who with some relative confidence would tell people that she could understand Tatar but not speak it, interacting with other Tatars dealt a major blow to that confidence. I realized for the first time that many of my relatives who spoke to me in Tatar would extensively mix Tatar and Russian words allowing me to understand broadly what they were talking about. However, at this Sabantuy there were many Tatars who spoke Tatar and English fluently, but not Russian, and did not mix the languages as much if at all.

The Tatar community in California had existed from before the 1960s when Tatar families who had emigrated to China, Japan, and Korea after the Russian Revolution came to the United States. The descendents of these families maintained their Tatar culture and language through events such as the annual Sabantuy, but, unlike the more recent immigrants, they did not speak Russian.

The other parts of Sabantuy were very much how I remembered them. There was a lot of food, both Tatar and other. The games were lively and kept the children busy. There was even a pinata which, while not being traditionally Tatar, is a common sight at celebrations in California and certainly fits the joyous and inclusive spirit of Sabantuy.

You Might Also Like

Yhyakh: A Summer New Year in the Coldest Place on Earth

The original Sakha is given for some terms in parentheses. Photographs provided by Mitrofan kyyha Varvara Egorova-Dygyia, Susan Crate, and Kathryn Yegorov-Crate. Yhyakh (ыһыах) is the Sakha people’s annual summer festival during which Sakha make offerings to sky deities known as aiyy (айыы) and make merry before the laborious hay-cutting season. Yhyakh is often rendered […]

Halva, Halwa, Helva: A Hundred Sweets from Dozens of Cultures

Halva, the rich dessert well-loved across many cultures, is so densely filling it almost manages to feel like a meal – and not an entirely unhealthy one at that. There are more than one hundred varieties of halva, an ancient dish whose base can be flour, ground seeds or nuts, or fruit, depending on where […]

Religion in the USSR: Моя Россия Blog

In this text, Tajik blogger Roxana Burkhanova describes, in Russian, the history and religions under the USSR. Despite the state’s officially athiestic policies, multiple religions existed within the USSR. Since that empire’s demise, all of those religions are now experiencing a revival. The material below details how this came to pass. This is part of […]

Islam in Russia: Моя Россия Blog

In this text, Tajik blogger Roxana Burkhanova describes, in Russian, the history and current status of Muslims in Russia. Islam is the largest minority faith in Russia and Muslims are a growing and important demographic there, especially among immigrants from Central Asia. The material below details both the challenges that Muslims have faced in integrating […]

Lagman: The Noodles of the Silk Road

Lagman is a dish that is very common in Central Asia, China, and many Middle Eastern countries. It can also be found in Russia and the Caucasus and is a popular dish among the Crimean Tatars. The basic recipe, which combines noodles with meat, has hundreds of variations. In Uzbekistan, the dish tends be a […]