The original Sakha is given for some terms in parentheses.

Photographs provided by Mitrofan kyyha Varvara Egorova-Dygyia, Susan Crate, and Kathryn Yegorov-Crate.

Yhyakh (ыһыах) is the Sakha people’s annual summer festival during which Sakha make offerings to sky deities known as aiyy (айыы) and make merry before the laborious hay-cutting season. Yhyakh is often rendered in English as the “Sakha New Year” or “Sakha Summer Solstice Festival.” The Sakha Republic is regularly cited as the coldest inhabited place on earth. Thus, the summer festival here takes on a special significance in celebrating the warmer weather and in preparing for the next long winter.

Origins and Development of Yhyakh

Today’s yhyakh festivals incorporate many of the myths surrounding the ethnogenesis of the Sakha. Legend holds that over half a millennium ago Elley Bootur (Эллэй Боотур), the mythic founder of Sakha culture, created the yhyakh festivals when he first prayed to Urung Aar Toyon (Үрүҥ Аар Тойон), the Creator. It was not until the arrival of European explorers in the early 1600s that accounts of yhyakh were recorded and, even then, these accounts provided incomplete pictures of the intricate festival. Thus, the form and structure of early yhyakhs can only be approximated.

Cultural connections between the Sakha and other Turkic-speaking peoples of Siberia and Central Asia can be seen in the commonalities held between yhyakh and Central Asian pastoralist festivals. These include a similar calendar, reverence of horses and cattle, the drinking of kymys (fermented horse milk), as well as similarities in the sacred architecture, traditional regalia, rituals, mythology, and beliefs.

The festival can also be seen as similar to other major festivals worldwide. It is the major expression of the ancient religious and cosmological beliefs of the Sakha, but also firmly tied to agricultural production and physical survival. Throughout its celebration, the Sakha appeal to the benevolent aiyy (sky spirits) for the right weather conditions to ensure the success of the harvest and herd as they prepare for the long, harsh winter. Yhyakh was, in fact, mainly practiced among the more southern Sakha who bred horse and cattle.

Yhyakh also served as time when wider communities of Sakha would come together. In the Sakha homeland, this was particularly important. Prior to collectivization in the 20th century and with the exception of Sakha who lived in port towns, Sakha families lived in geographically compact and remote units known as alaas (алаас). Alaas literally translates to “meadow in the forest,” and generally consists of a permafrost-based ecosystem composed of a cryogenic lake surrounded by meadows that transition to taiga (boreal) woodlands. Each alaas would generally support a single family and today, while few Sakha still live in these units, ancestral alaas are central to modern Sakha identities.

The alaas system meant that yhyakh was traditionally the year’s only time for mass social interaction and was thus the perfect justification to don one’s finest clothes, to visit with friends and extended family, and for young folk to meet, court, and marry.

The vast geographic area the Sakha inhabit meant that there were and are many different yhyakh festivals held, with the specific celebratory form varying from clan to clan. Nevertheless, central aspects and functions of the festival were and are similar.

Changes to Yhyakh Over Time

Yhyakh has undergone significant transformations, particularly over the course of the turbulent 20th century.

Under Soviet leadership the festivals progressively took on an ideological and political form and content. The principal function of sovietizing yhyakh was to change the festival’s symbolic meaning to one informed by the myth of voluntary collectivization. In diminishing the “national character” of yhyakh, Soviet authorities aimed to transform the sacred holiday into a public Labor Holiday.

Ritual ceremonies that often relied on significant improvisation became Soviet ceremonies with strict, set schedules. The opening ceremony resembled a formal meeting during which reports of labor achievements were read and awards presented to top-producing workers. This was typically followed by some concerts and performances. Even in this pared down form, yhyakh was generally permitted only in rural areas of the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Yakut ASSR) and was prohibited in urban areas, namely in the capital of Yakutsk. However, despite these mandated changes and repression, yhyakh remained a central part of the culture.

With the fall of the USSR, Sakha society, like all of those that once lived under the USSR, experienced significant sociopolitical transformation. During the 1990s, interest in Sakha national history and cultural heritage was reinvigorated, which ultimately led to the rehabilitation of the yhyakh festival as a central ethnic tradition. It was established as an official holiday in the Sakha Republic in 1991 with many traditional elements revived.

Today yhyakhs happen across the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), which is part of Russia. The festivals, which often last one to two days each, occur in mid-to-late June with many cities, towns, and villages all holding their own festivals. The staggering allows for people to travel to different yhyakhs—a practice that has recently increased with the institution of the Yhyakh Olongkho, named for the Olongkho, the national epic of the Sakha. The itinerant Yhyakh Olongkho travels between the republic’s various districts.

The capital city of Yakutsk holds the largest festival, the Yhyakh Tuymaada, which often draws up to 200,000 festivalgoers. This celebration is held yearly in Us Khatyng, an enormous glade and a Sakha sacred site where, according to myths, Elley performed the first aiyy-worshipping ceremony centuries before.

Opening Morning and the Ohuokhai

The Yhyakh Tuymaada and other larger two-day yhyakhs are typically structured similarly. The morning of the first day, festivities commence with the archy tuhulgete (aрчы түһүлгэтэ), a ritual purification and blessing of the festival guests. This is done as they walk through the aan aartyk (aан aартык), the festival grounds’ ceremonial entrance arches. The archway represents the boundary between the world of aiyy and the mortal realm. Greeters are purified as they enter this new world by greeters who lightly brush them with a horsetail known as a deibiir (дэйбиир).

Festivalgoers then often go to pray at the Aar Kuduk cherchi mas (Аар Кудук чэрчи мас), the sacred tree of life. The opening ceremony starts at midday. A shaman begins the ceremony by lighting a fire. He then offers kymys, which is fermented horse milk, alaadjy (алаадьы), which is a type of pancake, and salamaat, which is a mixture of butter and flour, to the aiyy sky deities via the fire. The shaman sprinkles the kymys while exclaiming the name of the festival: “yhyakh!” This word comes from the Sakha verb ys, which means “to spray” or “to sprinkle.”

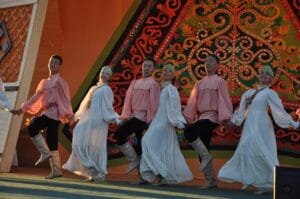

In this process, the shaman is accompanied by seven girls dressed as white cranes and eight boys dressed as booturs (боотур), which are traditional Sakha warriors. They assist him in feeding the fire.

After this, a ritual call-and-response prayer is led by the shaman. This results in a spiritual self-cleansing known as archy (арчы). Then more alaadjy and kymys are passed around to the audience in addition to horsemeat.

At this point, regional or local leaders often make speeches, wishing everyone a good Yhyakh.

Next, the first ceremonial circle dance, known as an ohuokhai (оhуохай), is held. Ohuokhai frames the whole festival and is danced throughout the festivities and well into daybreak the next day. Ohuokhai is one of a small number of Sakha traditions that have been continuously maintained and is commonly, although ununiformly, shared among all Sakha. Interestingly, the Sakha word for dance, unkuu (үнкүү) comes from the verb unk (үнк), “to pray” or “to worship.”

To perform the ohuokhai, participants form a circle, link arms and interlock fingers; then they begin moving in a clockwise direction around a wooden hitching post – a traditional symbol of cow and horse breeding, which is central to Sakha traditional livelihood. Dancers step with the left foot forward and right foot back.

The leader of the dance, known as the ohuokhaidjyt (оһуохайдьыт) sings out seven-syllable, improvisational, poetic verses and participants echo the leader’s lines. When the ohuokhaidjyt is finished weaving their story, they cue a new ohuokhaidjyt to take over.

According to Sakha belief, the power of language is so great that it has its own spirit, or ichchi (иччи). This spirit empowers the words to fulfill their own meaning when they are uttered during the ohuokhai, giving the dance a word-to-flesh supernatural aspect. Many Sakha speak of the ohuokhai as an intense force that draws its otherworldly, and sometimes healing, powers from the expressive language and entrancing collective rhythm. Tales are told of people dancing ceaselessly for hours, old folks who could otherwise barely walk would transform into sprightly youth again, and people who enter the circle are charged with energy for the forthcoming winter.

Further, ohuokhai have functioned as public forums where ohuokhaidjyt freely speak their minds. Social and political issues can arise, and this dialogue passes from song leaders to participants. Allowing for ceremonial dissent, even in societies where taboo or censorship are common, has been part of many societies’ festivals. Soviet authorities also attempted at times to co-opt the tradition, holding formal contests for singers, and requiring that all song texts be composed in advance and submitted for approval. This, of course, stifled the innate creative improvisatory quality of ohuokhai and stripped it of its function as a public forum. Nevertheless, in outlying provincial areas further from central authorities’ gaze, ohuokhai endured, more or less in its traditional form.

The Yhyakh Grounds

Aside from the aan aartyk (aан aартык) ceremonial entrance arches, the sacred tree of life, and a large, open area for ohuokhai, yhyakh fair grounds often have several other specific areas and buildings. For example, there are often exhibition buildings for showcasing the works of metal and wood masters. Sometimes there are traditional housing units erected like balaghan (балаҕан), a wooden house, or a uraha (ураһа), a summer tent-pavilion. These both showcase Sakha heritage in and of themselves, and also sometimes house exhibitions such as a recounting of the lives of important Sakha elders.

There are also other spiritual places, such as for areas for worshipping the Earth Goddess, Aan Alakhchyn Khotun aiyy sitime (Аан Алахчын Хотун айыы ситимэ) and for the kunu korsuu (күнү көрсүү), which is the greeting of the sun ceremony and which will be described below.

The festival eating grounds are known as a khorchuoppa (хорчуоппа) and usually feature both picnicking pavilions and food vendors. There are special places for collective kymys drinking and usually multiple stages and arenas for performances and sporting competitions.

While there are some times when everyone gathers for a single event, such as ohuokhai, or to greet the sun, events are often run concurrently and festivalgoers move between them, taking in what interests them most.

Yhyakh Traditional Foods

After the opening ceremonies, people gather to eat with family and friends at the khorchuoppa (хорчуоппа).

Many of the foods traditional to yhyakh are made from dairy products. Summer is a time of milk abundance, when cattle and mares graze in green pastures. Thus, kymys is drunk but so is byrpakh (бырпах), which is fermented cow’s milk, and suorat (суорат), which is kefir. Suogei (сүөгэй) or fresh cream, is also popular as is salamaat (саламаaт), the food made from flour mixed with butter or suogei. Although less frequent now, there were customarily kymys– and butter-drinking contests. In fact, the traditional holiday greeting, Urung tunakh yhyaghynan egherde! (Үрүҥ тунах ыһыаҕынан эҕэрдэ) translates to something like “dairy products yhyakh, congratulations!”

Meat and fish products are also heavily consumed. In addition to horse meat, other staples on offer include carp, cow tongue, and uos tardar (үөс тардар), a dish of boiled meat.

Various types of sausage can be found like khaan (хаан), which is a blood sausage, and simii (симии), which is made from meat and offal. Delicacies are eaten like tansyk (тансык), which is minced raw foal meat mixed with fat and spices, and chokhochu (чохочу), which is thinly sliced beef or foal liver). Other delicacies include kharta (харта), which are boiled colt intestines served either hot or cold, and silii (силии), which is marrow.

Various breads are eaten. In addition to the alaadjy, leppieske (лэппиэскэ), a flatbread, and vafly (вафли), or waffles are common. Bereski (бэрэски), which are Russian meat buns, are also eaten during the festival.

Yhyakh Sports and Performances

As is also common to many festivals, contests and performances are held throughout the day. The number and diversity of contests correlate to the size of the overall festival itself, but staple competitions often include best national cuisine, best national regalia, best examples of different folk arts, and a wide array of performance-based and sports-based competitions.

There are also performances given for the sake of performance, such as children performing skits, singing songs, or reciting poetry or bits of the olongkho, the Sakha national epic. Local singers and choirs sing songs about yhyakh or their homeland. People also compete for best ohuokhaidjyt as well as in playing the khomus (хомус), a traditional Sakha mouth harp. Toiuk [тойук], a solo improvisational song, and chabyrghak (чабырҕах), a fast composition weaving together stories and jokes in tongue-twister fashion, are also traditional Sakha art forms in which competitions are often held.

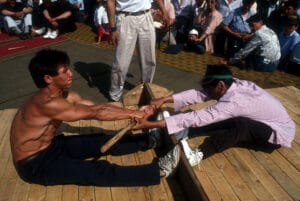

National sports contests often begin in the late afternoon. The most popular is wrestling. Sakha wrestling, which has its own rules and was once used primarily to train warriors, is known locally as khapsaghai (хапсаҕай), which literally means “a contest in agility.” The sport is a beloved part of the Sakha national heritage. Stick-wrestling is another unique form usually on display and is known as mas tardyhyy (мас тардыhыы). In stick-wrestling the opponents sit facing each other with a board separating them. Holding a single stick between them, they must pull the other over the board to win. Freestyle wrestling matches are also often held.

There is also an assortment of “strongman” sport disciplines. Us togul us (үс төгүл үс), which literally means “three times three,” features three kinds of jumping: on one leg, long jumps on alternating legs, and flatfooted jumps from both feet. And, of course, you can’t get more strong man than taahy kotoghuu (тааһы көтөҕүү), a sport of boulder carrying.

Archery and long distance running typically round out the list and the game competitions culminate with equestrian games known as at suuruute (ат сүүрүүтэ) in the evening.

Long ago these sporting competitions were reflections of the clan-based social character of yhyakh. Men competed to demonstrate their capabilities as warriors and for clan heads to assess the strength of their regiments. Today, participants compete in the hopes of winning prizes, the biggest of which is typically for khapsaghai, Sakha wrestling.

Greeting the Sun

Activities continue throughout the night. It never becomes completely dark during summers in the Sakha Republic, but in areas south of the Arctic Circle, the sun dips below the horizon for a while, creating a twilight in the middle of the night. Then, around two in the morning, twilight fades and glowing red streaks begin to spread across the sky and people will raise their arms, their palms facing the rising sun in a ceremony known as kunu korsuu siere-tuoma (Күнү көрсүү сиэрэ-туомa), or The Greeting of the Sun. This is thought to reenergize people for the approaching nine months of winter. Then an ohuokhai is danced and, if the festival is on its last day, the festivalgoers will often head home. However, it is at this point that the next day of festivities, if they are planned, will flow straight from the first for multi-day festivals.

Personal Notes on Yhyakh

My favorite yhyakh is hosted by my paternal village, Elgeii (Элгээйи), and held at the bucolic glade of Ugut Kuol (Угут Күөл) a place name which translates to “The Great Lake.” People who grew up in or around this area have deep attachments to Elgeii and often return yearly for the festival. At Ugut Kuol, I know most everyone I come across and relish frequent stops to visit with ebeler (эбэлэр) and emeekhsinner (эмээхсиннэр), which are affectionate terms for older women. They still pinch my cheeks and tell me all about their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

The wrestlers who compete in khapsaghai are local young and middle-aged men from my village that, in many cases, I know and can root for. The grand prize, often a car, is then seen and recognized around town for years to come. I feel a greater connection to the folks whose fingers are locked with mine during ohuokhai, which is danced on the same land where my grandfather Mitrofan, a renowned ohuokhaidjyt, wove his poetic verses.

I have also attended other yhyakh festivals, including the enormous Yhyakh Tuymaada. Here, the crowds can often reach up to 200,000. They not uncommonly are used to set Guinness World records in things like “largest ohuokhai dance,” which happened in 2012 when 15,293 people, all dressed in traditional costume, formed thirty-six concentric circles and were led by the great ohuokhaidjyt Aleksandr Vasilyevich Savvinov.

While I enjoy the spectacle of the thousands of yhyakh-goers and the numerous events happening simultaneously, and often the opportunity to see big name performers on stage, I personally find the larger yhyakhs to be quite overwhelming. Familiar faces are few and far between in and feeling spiritual connections can be difficult when trying to maneuver these crowds in weather that often exceeds 32ºC/90ºF.

In recent years, Yhyakh Tuymaada has become a popular tourist destination and tours from Europe stand out with their earpieces and tour guides brandishing flags and microphones. Although it can be a bit jarring to see so many newcomers at yhyakhs, it is gratifying to know there is such interest in the Sakha people’s most important religious holiday.

Yhyakh today, in cities, municipalities, and villages, is a living tradition that is simultaneously reflective of the past, in that it is a long-standing custom, and of the future, considering its ongoing evolution and continuous enrichment.