Sharing common roots, Russian and Ukrainian, at first glance, look very similar. This is not so. In reality Russian and Ukrainian have more differences than similarities.

The following is an article that originally appeared on Russian7.ru (Русская Семерка). The original can be read here. The following translation to English has been provided by Lindsey Greytak, who studied abroad with an SRAS internship.

From the Same Roots

Fact: In total, there are about 35 to 45 million Ukrainian speakers in the world. Native Russian speakers number around 260 million.

It is well known that Ukrainian and Russian belong to the same group of Eastern Slavic languages. They have a common alphabet, similar grammar, and significant lexical uniformity. However, the particularities in the development of cultures of the Ukrainian and Russian people led to noticeable differences in their language systems.

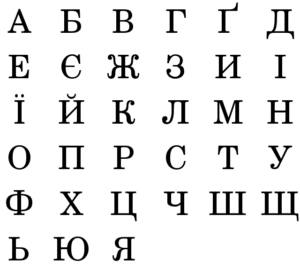

This first difference between Russian and Ukrainian is apparent in the alphabet. The Ukrainian alphabet took shape at the end of the 19th century, and it differs from Russian in that Ukrainian does not use the letters Ёё, Ъъ, Ыы, Ээ, but does have Ґґ, Єє, Іі, Її, which are not present in Russian.

Consequently, uncharacteristic in Russian pronunciation are some sounds of the Ukrainian language. Thus, absent in Russian is the letter “Ї”, which sounds closer to “ЙИ”, the “Ч” is pronounced more harshly in Ukrainian, like in Belarusian or Polish, and “Г” is produced with a guttural, fricative sound.

For more on Ukrainian pronunciation, see this Talking Ukrainian Phrasebook.

Close Languages?

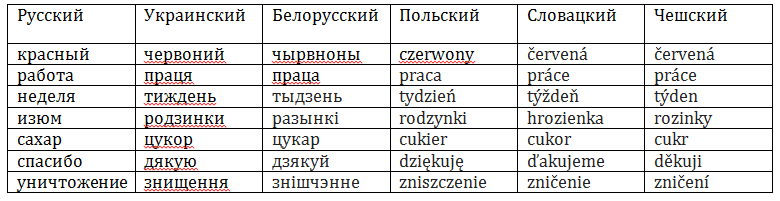

Modern research shows that the Ukrainian language is closer to other Slavic languages: Belarusian (29 common characteristics), Czech and Slovak (23), Polish (22), Croatian and Bulgarian (21), and only 11 common characteristics with Russian.

Some linguists, on the basis of these facts, even place doubt that Russian and Ukrainian should be placed in a single language group.

Statistics show that only 62% of words shared between Russian and Ukrainian have common characteristics. Therefore, the Russian language in relation to similarities with Ukrainian, sits at fifth place behind Polish, Czech, Slovak, and Belarusian. To note in comparison, English and Dutch are lexically more similar at 63% in shared common characteristics, which is more than Russian and Ukrainian.

As they are both Slavic languages, students who have studied Russian often have an easier time learning Ukrainian.

Divergence of Paths

Fact: Only 62% of words have common characteristics between Russian and Ukrainian.

The differences between the Russian and Ukrainian languages are largely due to the particularities between the formation of two nations. The Russian nation centralized its formation around Moscow, which led to the dilution of its lexicon with Finno-Ugric and Turkic words. The Ukrainian nation was formed by the unification of Slavic ethnic groups, and therefore the Ukrainian language to a considerable degree has retained its ancient origins.

By the middle of the XVI century, Ukrainian and Russian already had significant differences.

Texts of that time in the Old Ukrainian language are generally understandable to modern Ukrainians, but for example, documents from the the epoch of Ivan the Terrible are more difficult to understand by modern Russians.

Even more noticeable discrepancies between the two languages began to develop with the beginning of the formation of the Russian literary language in the first half of the XVIII century. The abundance of Church Slavonic words in the new Russian language made it hard to understand for Ukrainians.

For example, Old Russian takes the Church Slavonic word «благодарỳ/blagodaru» thank you, and is known to Russians today as «благодарю/blagodaryu». The Ukrainian language, on the other hand, preserved the old Russian word «дáкую» for thank you, which now looks like «дякую» in modern Ukrainian.

From the end of the 18th century, the Ukrainian literary language began to take shape, which being on course with other pan-European languages, gradually broke away from its ties to the Russian language.

In particular, a rejection of Church Slavonicism occurred, instead there was a focus on folk dialects, as well as word borrowing, primarily from other Eastern European languages.

The following table visually shows how much closer the basic vocabulary of Modern Ukrainian is to other Eastern European languages and how far it is from Russian.

Also important, especially in Ukrainian, is its dialectical diversity. This is a result of individual regions in Western Ukraine having been part of states such as Austria-Hungary, Romania, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. So, the dialect of a resident from the Ivano-Frankivsk Region in western Ukraine is always understood by someone from Kyiv, while a Muscovite and a Siberian also speak the same dialect.

False Friends in Russian and Ukrainian

Fact: In Ukrainian the word «жаль» (pity/sorry) may also be used as a noun. «Ой настала жаль туга да по всій Україні» (It was such a pity for all of Ukraine).

Despite the fact that Russian and Ukrainian have many common words, and even more words similar in pronunciation and spelling, they nevertheless often possess different semantic nuances.

Take, for example, the Russian word «иной» (different/other) and its related Ukrainian word «iнший» (another). The sound and spelling of these words are similar, but their meanings have noticeable differences.

A more accurate correspondence to the Ukrainian word «iнший» in Russian would be «другой» (other), but it is somewhat more formal and does not bear such emotional and artistic expressiveness as the other Russian word «иной».

Another word, «жаль» (pity/sorry), is identical in both languages in spelling and pronunciation, but there are differs in its semantic meaning. In Russian the word is used as a predicative adverb. Its main task is to express regret for something, or pity for someone.

In the Ukrainian language, when used as an adverb, the word «жаль» has a similar meaning to Russian. However, it can also be a noun, and as a noun its semantic nuances are noticeably enhanced in accordance with words such as grief, bitterness, and pain. «Ой настала жаль туга да по всій Україні» In this context, the Russian version of the word «жаль» is not used.

Divergent Grammar in Russian and Ukrainian

It is it often possible to hear from foreign students that Ukrainian is more closely related to other European languages than to Russian. It has long been noticed that translating from French or English into Ukrainian is in some respects simpler and easier, than translating into Russian.

Everything has to do with certain grammatical structures. Linguists have a certain joke that in European languages one says «поп имел собаку» (The pope had a dog), and only in Russian «у попа была собака» (With the pope was a dog). Indeed, in Ukrainian in similar cases, along with the verb «есть» (is), the verb «иметь» (have) is also used. For example, the English phrase “I have a younger brother” in Ukrainian can be said like «У мене є молодший брат» (With me is a younger brother), but also, with equal meaning, «Я маю молодшого брата» (I have a younger brother).

Fact: The name of the «Українська мова» (Ukrainian language), a common language throughout the entire ethnic territory, was spread and consolidated only in 20th century.

The Ukrainian language, in contrast to the Russian language, adopted modal verbs from other European languages. So, in the phrase «Я маю це зробити» (I have to do it), the modal verb is used with the meaning of obligation – like in the English “I have to do it.” In Russian, this function of the verb «иметь» “to have” has long since disappeared from use.

Another indicator in the differences in grammar is that the Russian verb «ждать» (to wait) is transitive, but in Ukrainian «чекати» (to wait) is not transitive. Thus, in Ukrainian the verb is used with a preposition «чекаю на тебе» (I wait for you) – like in English. In Russian the verb is used without a preposition «жду тебя» (literally: “I wait you”).

However, there are cases when Russian borrows from other European languages and Ukrainian does not. Thus, the names of the months in Russian are copied from Latin: for example, «март» is March in English, martii in Latin, März in German, mars in French. Here, the Ukrainian language has retained the connection with its original Slavic vocabulary using the word «березень» (berezyen’) for the month. This name is actually taken from the word for “birch tree.”

Additional Resources for Understanding Ukrainian

Ukrainian Holidays 2026: A Complete Guide

Ukrainian holidays are a reflection of Ukrainian’s recent political history and shifting identity. They feature a range of secular and religious holidays. Some holidays have been celebrated for thousands of years and some, particularly patriotic and Western-influenced holidays, have been recently added to the line up. See below for descriptions of these Ukrainian holidays, their […]

Kupala: Ancient Slavic Midsummer Mythology and its Modern Celebration

Kupala is an ancient Slavic holiday celebrating the summer solstice, or midsummer. Once part of a series of annual rituals, it marked and was believed to sustain agricultural cycles—essential to early human survival. Held as vitally important, these pagan traditions remained deeply rooted even after Christianization, technological change, and centuries of oppression tried to dislodge […]

Kulich, Paska, Nazuki: The Easter Breads of Eastern Christianity

Easter breads such as kulich, paska, choreg, and nazuki are delicious Easter traditions. Easter is by far the most important religious holiday for those practicing Eastern Christianity. In addition to church services and egg dying, the holiday is also marked across the cultures by ritual bread baking. Despite the wide geographic area covered by Eastern […]

Maslenitsa, Masliana, Meteņi: Spring Holidays of the Slavs and Balts

Rites of welcoming spring and saying goodbye to winter are some of the oldest holidays preserved across Slavic cultures. In the Baltics, the celebrations were nearly lost after being suppressed by Catholic and imperial dominance. Today, Russia’s Maslenitsa is by the far the best-known, but multiple versions exist across the diverse Slavic landscape. In the […]

Pierogi, Pīrāgi, Varenyky: A Tour of Pastries and Dumplings

The dumplings and pastries of Europe’s northeastern flank have a story to tell. Their recipes, etymologies, and related traditions are intertwined in a complex historical knot. There are so many ancient connections that it is almost impossible to say which influenced the next. And yet, each dish is held up as a unique and integral […]