Russian, like most languages, is full of idioms. Some of these are very close to those used in other languages while others are quite specific to Russian. Many have been in use for so long that their origins are now unclear while some have clear origin – or at least probable. The following article is meant to assist students studying Russian with SRAS abroad as well as anyone else interested to better understand a few of these colorful phrases.

We’ll focus on three main origins: idioms derived from French, from professional jargon, and from the cold or winter weather.

I. From the French

In the 18th and 19th centuries, French culture was perhaps the world’s most highly respected. French became so widely spoken across the globe that we still say that a language is a “lingua franca” when it is used by large number of people as a second language to communicate in. At that time, it became widely used as the main language of the Russian aristocracy, used to set themselves apart from commoners and display their education and cultured upbringing. This led to the adoption of many words and popular expressions from French or developed with words that were originally French.

(Incidentally, if you are interested in how Russian has been influenced by other languages, check out this article on the Mongol influence that can be seen in modern Russian.)

Вешать лапшу на уши

The expression “вешать лапшу на уши” means “to lie to someone” or, literally, “to hang noodles on ears.” This phrase most likely came from the French “La Poshe” which means “the pocket” and was nickname for pickpockets who, as part of their scam, would sometimes clap people on their shoulders and quietly steal from them while asking some mundane question.

Perhaps misunderstood by Russians that did not know the French very well, or perhaps simply used in jest, the word morphed into a single Russian word that sounds very similar to the French “La Poshe”: “лапша,” which means “noodles” in Russian. The full phrase then likely evolved as an attempt to place the oddly-used word in some context that made sense.

In criminal slang, “лапша” also came to mean a case which was fabricated to imprison someone when there was not enough evidence.

Вернемся к нашим баранам – Back to the Sheep (Point)

“Вернемся к нашим баранам” is another phrase that entered Russian through French influence. It means “let’s get back to the point,” and literally translates to “we return to our sheep.”

The phrase originated in a French court in the Middle Ages. Apparently, sheep had been stolen and the defendant’s attorney had not paid the plaintiff for some fabric. The hearing kept switching to the issue of the fabric, when the case at hand actually concerned the sheep. It eventually became comical when the judge was forced to admonish those present to “please get back to the sheep.”

Дело в шляпе – The Deal is in the Hat (Bag)

The word “шляпa” also came from French, where the word for “hat” is “chapeau.” The (morphed) word entered Russian at the end of the 1500s, and was originally used to refer to most types of non-Russian hats. The word’s meaning eventually expanded to include any hat.

The Russian idiom “дело в шляпе,” a phrase that means “it’s in the bag” or, literally, “the deal is in the hat,” has several likely origins.

One of the most likely is that “гонцы, чтобы не потерять важные бумаги, зашивали их под подкладку шапки или шляпы” (“messengers, in order not to lose important papers, sewed them up into lining of their cap or hat”). Particularly those messengers coming from abroad would have reason to want keep the messages safe over a considerable time and perhaps keep them secret as well.

Another possible origin comes from the fact that sometimes, “чиновники, разбиравшие дела, брали взятки в шляпы” (“officials who heard cases would accept bribes placed in their hats”).

And still another version holds that the idiom comes from a tradition of settling arguments or deciding issues by drawing lots from a hat. The person who drew the winning lot would be granted the right to, for instance, trade in a certain product in a particular location or would win a government contract.

“Дело в шляпе” in modern Russian can also have more general meanings such as “всё будет в порядке” (everything will be all right), “дело почти сделано” (work is about to be done / the deal is about to be concluded), or “дело удается” (things are going well).

II. From Professional Work

Russian also has several expressions connected with professions and professional behaviors. These include both those that that express respect and those that deride.

Точить лясы – Carve Spindles (Idle Talk)

One popular expression was once positive in meaning and later became derogatory. “Точить лясы” (wag one’s tongue) literally means “to carve spindles.” Traditional Russian wooden houses are famous for their woodwork, often with delicate lattices around windows and over the roofs. The handrails on the porch are often supported with intricate wooden spindles as well. Those “лясы” (also called “балясы” in Russian and “balusters” in English) are “точеные фигурные столбики перил у крылечка” (decoratively carved handrail pillars). Those that could create this type of woodwork were highly respected.

Initially, “точить лясы” meant “вести изящную, причудливую, витиеватую беседу” (to have graceful, fancy, florid conversation). Eventually, the term began to be more often used ironically and, over time, started to refer to “пустая болтовня” (idle talk).

Большая шишка – The Big Pinecone (Cheese)

For example, the expression “большая шишка” means “важный человек, большой начальник, босс” (an important person, manager, or boss) but literally translates to “big pinecone.” The pinecone, as the vessel of pine seeds, was known as the creator of the mighty forests that both provided ancient Russians with food and building materials but also with many sources of danger (wild beasts, poisonous plants, and occasionally thieves and invading armies would come through the forests). The pinecone thus was an important symbol of fertility and power in pagan times and retained its powerful symbolism even well into tsarist time, particularly among poor peasants and workers.

The specific expression “большая шишка” as it is used today originated from the language of бурлаки (barge haulers) who began to refer to the puller in the lead position as the “шишка.” This person carried the biggest and most important load while hauling a vessel. He was thus generally the strongest and most experienced of the group and, in fact, the earnings of the entire group depended on just how strong and skillful this person was at quickly and safely hauling the barge to where it needed to go. Calling this person by the name of an ancient talisman was considered a compliment and, most likely, a way of wishing good fortune upon the group.

Тертый калач – Kneaded Loaf (Tough Nut)

Another positive expression is “тертый калач” (a kneaded loaf). The term refers to an “очень опытный человек, которого трудно обмануть” (a very experienced person who is difficult to be deceived/tricked).

A калач (kalach) is a traditional bread usually formed as a ring and often braided. A тертый калач is made from special dough and kneaded for an exceptionally long time. This type of калач is a favorite as the extreme work produces a loaf that is extremely soft, delicious, and thick.

In the Russian language, the verb “тереть” usually means “grate” or “rub” but can more generally refer to the action of “to run to and fro onto the surface with hard pressing” (водить взад вперед по поверхности с большим нажимом). The expression uses the verb “тереть” metaphorically and assures us that life’s “kneading” makes one’s character stronger. For those interested, the Russian TV show Galileo covered this phrase and the particular loaf in a 7.5 minute segment. It’s in Russian, but relatively slowly spelled out and with a lot of visuals to aid understanding.

Incidentally, a person who made калачи became known, as a profession, as “калачников” or “калашников.” This, in turn, eventually became a last name handed down to ancestors (just like “Baker” in English) and is thus a source of the name a famous Russian automatic weapon. The Kalashnikov is named for its inventor, Mikhail Kalashnikov.

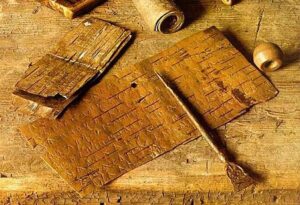

Филькина грамота – Filkin’s Letter (Semiliterate Writing)

Finally, an example of such an expression with an entirely negative meaning is “Филькина грамота.” This specific expression is likely still popular because writing in Russia, especially for anything expected to have professional or legal weight, is expected to be letter-perfect and without corrections. Anything less should be thrown out and begun again from scratch.

“Филькина грамота” refers to any document that is “невежественный, безграмотно составленный или неправильно составленный документ” (written ignorantly, with many mistakes in spelling or grammar, and/or not having legal weight).

In ancient times in Russia, Филя or Филька was a name often used by common people. To call anyone from the ruling classes by this name would have been an insult. It was often used, particularly by the nobility, to refer to anyone deemed gullible, naïve, or stupid.

This expression was popularized by Tsar Ivan the Terrible when Philip II, Metropolitan of Moscow, sent a letter to Ivan denouncing the tsar’s creation of a secret police force and that organization’s subsequent imprisonment and torture of many people who were suspected of being traitorous. Ivan the Terrible called the letter “Филькина грамота” and then had the Metropolitan arrested and killed.

While the fate of a modern producer of a “Филькина грамота” is certainly not likely be as harsh, the term is still popularly used and can be thought of as the speaker giving the document’s writer an “F.”

III. From the Cold

Russian also has many sayings that reference cold or winter activities to make their point.

If the influence of cold on the Russian language interests you, definitely check out the article on our site entitled “Winter Wear as a Cultural Phenomenon in Russia.”

Любишь кататься – люби и саночки возить – Love to Sled, Love to Pull

Ok, so this one is technically a proverb, but it’s one of our favorites…

The phrase любишь кататься – люби и саночки возить is commonly used among Russians to reference the value of hard work during moments of winter fun with their children. It can also be used to remind someone in any context that one must work to obtain the things one desires.

The phrase literally translates as “(if) you love to sled, (you must) also love pulling the sleigh (uphill).”

Лёд тронулся – The Ice Has Broken

In English, “to break the ice” has a very specific meaning – referring to an action that can bring two previously separate people together in some way.

In Russian, “лёд тронулся” generally refers to any breakthrough. Perhaps the most well-known use of the phrase is in the famous story The Twelve Chairs. In that story, the main character, the con artist Ostap Bender, says it whenever he feels he’s getting closer to the loot he seeks.

The word can also refer to that moment when a person becomes emotional or starts to show their feelings. For instance, the pop song “Лёд тронулся” speaks of the moment that two people touch and passion ignites. (Лёд тронулся, когда ты до меня дотронулся).

The phrase is very often used when something that has been worked for or long-awaited happens, particularly referring to a scientific breakthrough or a business reaching a milestone. Лёд тронулся. Дело началось. (The ice broke and the business was launched.)

Как снег на голову – Like Snow on the Head (Out of the Blue)

One idiom that is particularly easy to visualize is “как снег на голову.” It refers to something that hits you like a large amount of snow falling on or hitting your head. This is usually used in the same context as the English “out of the blue” and usually refers to something that is, in addition to happening suddenly, also shocking to the person affected.

For instance, coming home and finding your house full of guests, going to the store and finding the prices much higher than expected, or the sudden appearance of any problem can be described as “как снег на голову.”

You’ll Also Love

Russian MiniLessons: Thankfulness

The following bilingual Russian MiniLesson is meant to build your vocabulary by providing Russian phrases within English text. Hover over the bold Russian to reveal its English translation. This topic is doubly pertinent this month, as has just passed, but also because many are likely to be affected by the new law on NGOs. The […]

International Women’s Day: Local Culture and Celebrations

International Women’s Day was first celebrated in St. Petersburg in 1913, declared by activists there and celebrated with rallies that demanded more rights. It did not become an official state holiday and day off, however, until 1965. In that year, March 8th was chosen as it marked the day when, in 1917, women again marched […]

Russian MiniLessons: Death in Russian Folklore and Culture

The following bilingual Russian MiniLesson is meant to build your vocabulary by providing Russian phrases within English text. Hover over the bold Russian to reveal its English translation. Russians are often superstitious and regard discussions of death or illness as unpleasant or even dangerous. However, as with all cultures, death does play a significant part […]

Russian Greetings Through the Ages: Vocabulary and History

Greetings are an important part of Russian culture. These greetings have evolved through the ages, reflecting first pagan worldviews and then Christian. Modern Russian greetings are rooted deep in a tradition of showing respect, building community, and often offering blessings of health. Let’s take a look at how greetings have changed in Russian over time. […]

Russian MiniLesson: The Russian Soul and Related Russian Vocabulary

Many well-known people from various countries have acknowledged that Russia and the Russians have unique features that can be difficult to explain. For example, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill once said that “Россия – это головоломка, завернутая в тайнувнутри загадки” (Russia is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma). A part of this mystery is […]