Pryanik (Пряник), commonly described as “Russian gingerbread” or “Russian spice cookies,” is a sweet bread or cookie flavored with spices and sometimes filled with jam, sweetened condensed milk, or caramelized milk. Spices used can include cardamom, cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, cumin, and anise, but recipes can vary fairly widely and many Russian regions have specific Pryanik recipes and forms that are beloved local traditions.

Pryanik (Пряник), commonly described as “Russian gingerbread” or “Russian spice cookies,” is a sweet bread or cookie flavored with spices and sometimes filled with jam, sweetened condensed milk, or caramelized milk. Spices used can include cardamom, cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, cumin, and anise, but recipes can vary fairly widely and many Russian regions have specific Pryanik recipes and forms that are beloved local traditions.

Why It’s Called “Pryanik”

(Почему они носят такое название?)

When the precursor of pryanik was first baked in the 9th century, it was made with rye-flour, honey and berry-juice, and known simply as “медовый хлеб” (honey bread). It was only in the 12th-13th century, when Russian trade with the Middle East and India first began, that spices were added, bringing the recipe closer to the gingerbread recipe that had been enjoyed in Western Europe since at least the 11th century.

Gradually, the smell and taste of the spices came to characterize the bread, and recipes featuring spices became the prevalent form of the food by the 15th century. However, it was only in the 17th and the name “медовый хлеб” was replaced with “pryanik,” which comes from the root word “пряность,” meaning “spices.”

Interestingly, this shift in name came at the same as Russia was pushing its borders and influence further south and securing positions along the Silk Road – the trade route that long supported commerce between Europe and the Orient. Among other things, Russia’s expansion into the route gave it increased access to silk, porcelain, and, of course, spices.

However, while pryanik became widespread in Russia, the use of spices did not, so it remains a fairly unique taste in Russian cuisine. Perhaps because of this, it has also found its way into a vast array of “пословицы и поговорки” (proverbs and sayings).

For example, Russians often use “кнут и пряник,” (literally: whip and pryanik) where an English speaker might use “stick and carrot.” When Russian peasants first heard of the quote “let them eat cake,” they apparently phrased it as “хлеба не станет, будем пряники есть” (there will be no bread, but we will eat Pryanik).

If someone wouldn’t do something for a million dollars, you might say that «и пряником не заманишь» (you couldn’t tempt (the person) even with Pryanikк). If something is music to your ears in English, in Russian it is «как пряник в ухе» (like pryanik in your ear). Someone can tell you to give yourself a pat on the back by telling you to «купи себе пряник» (buy yourself пряник).

Even the harder lessons in life can be shown with pryanik. For example, «без работы пряников не купишь» (you can’t buy a pryanik without working) tells us that we must work for what we want. «Ломается как дешевый пряник» is what you might say about someone who can never give in when arguing (as a cheap pryanik is often more like a brick than a cookie). However, sometimes that is how the cookie crumbles.

Pryanik can be baked as a larger loaf, or as smaller cookies, in which case the plural “пряники” is usually used to describe them.

When and How to Eat Pryanik

(Как правильно есть пряник?)

Pryanik, like most sweet things, were once baked only for special occasions. There is record that pagans in some parts of Russia once baked honey bread or pryanik in the shape of birds or animals and hung the cookies off of trees on certain holidays. This tradition lives on in certain northern areas of Russia and Scandinavian countries with gingerbread ornaments baked for Christmas trees (ёлки).

According to Russian TV program «Галилео», pryanik was used in the past as a marriage proposal: A young man would offer a lady a pryanik as an indication of his love. If she accepted the pryanik, wedding bells would ring!

Today, пряник is mass-produced and is served most often as a snack with tea or coffee. However, it can still signify a special occasion. For example, one cannot go to the Russian city of “Тула” (Tula) without bringing back a fresh “тульский пряник” (Tulskii pryanik), renowned for its elaborate embossed patterns and messages. In fact, probably no city takes its pryanik more seriously than Тула, which also has a whole museum dedicated to its tasty confections.

The tulskii pryanik and some other types of elaborate pryanik can be purchased at stores throughout the country and are sometimes used as “съедобные открытки” (edible cards), and presented to friends and family as gifts on holidays and celebrations. Interestingly, government officials in the Tula region once prepared a ballot box of their famous tulskii pryanik and presented it to the head of Russia’s central elections commission when he visited there.

How to Prepare Pryanik

(Как правильно готовить пряники?)

There are many types of pryanik, which can be differentiated just by their appearance. The normal, classic is simple in form – round with a white glaze. “Печатные пряники” (printed pryaniks) are made with the help of wooden or metallic pastry molds. These include the Tulskii pryanik from Tula, and “городецкий пряник” (Gorodetskii pryanik) from Gorodets in the Nizhny Novgorod region.

Other types of pryanik could be flat, shaped, or even molded and are often glazed or iced. As an example of the Christmas-tree pryanik mentioned above, there is a specific type of pryanik from the Arkhangelsk and Olonets regions of Northern Russia known as “козюли” (kozuli) or “лепные пряники” (molded pryanik). Coming from pagan origins, their shapes depict the figures of animals, usually taking the form of a horse, which was a symbol of the sun and a guard against evil, or a deer, the protector and a symbol of the continuing cycle of life. Traditionally, they were made by molding the pryanik dough to form the 3D-shaped cookie, but some are baked in 2D shapes, and decorated with icing to paint the features of the animal. Today, kozuli are used as Christmas decorations, and as ornaments for the yuletide tree. Kozuli derive their name from the Russian word for “goat,” which was once a powerful symbol of fertility and which is still a common shape for the cookies to take.

There are many different styles of pryanik, and a myriad of recipes for each style. Feel free to tweak the amount and types of spices used to flavor the pryanik. Concentrated juice can be used to color the dough and glaze. Add nuts or berries to fillings if you so please. A true “прянишник” (pryanik bakers; this was once a full-time profession in Russia!) should have their own secret recipe.

Pryanik Recipes!

(Давай приготовим!)

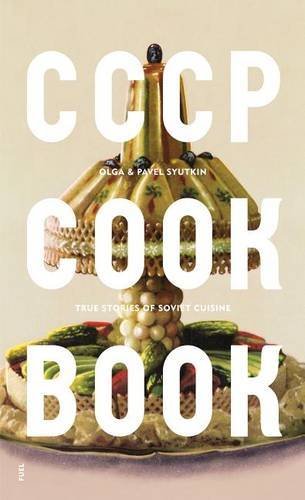

See below for a free recipe for various Russian pryaniki. See also the free videos online. If you are interested in cooking from Russia, Ukraine, Georgia, and other places in Eurasia, make sure to see our full, free Eurasian Cookbook online! You might also be interested in the following specialized cookbooks we’ve enjoyed:

|

|

|

|

| Домашние тульские пряники | Home-made тульский пряник |

Ингредиенты для теста:

Ингредиенты для глазури:

Способ приготовления:

|

Ingredients for the dough:

Ingredients for the glaze:

Method:

|

| Козюли | Kozuli |

Ингредиенты для теста:

Ингредиенты для глазури:

Приготовление

|

Ingredients for the dough:

Ingredients for the glaze:

Preparation

|

Our Favorite Videos about Pryanik

Make a pryanik cake with Russian celebrity chef Alexander Seleznev. He offers lots of good pointers for making a truly tasty pryanik.

Observe the making of a mass-produced pryanik with a range of toppings, designs, and fillings. This is promotional video for a Russian delicatessen chain called “У Палыча” that can be found in many places in western Russia.

“Покровский Пряник” (Pokrovskii Pryanik) is a company from the city of Vladimir that specializes in making pryanik. This promotional video takes you into their bakery, and shows the different types of pryanik, and the various fillings used.

This video from «Галилео», a television program on Russia’s СТС channel, provides a great introduction to tulskii pryanik, from the origins of its name, to the processes in which the molds and pastry are made. The video gives an interesting glimpse into how the intricate molds are carved, and the pryanik baking process.

You Might Also Like

Olga here turns her attention to the modern Russian circus, describing what it is like to attend a contemporary performance, from the atmosphere inside the circus building to the acts that still draw enthusiastic audiences today. Written in simplified, modern Russian, her account offers a firsthand glimpse into how a traditional cultural institution continues to […] Russians have typically gotten nearly three weeks off a year just for holidays. This has changed in recent years and especially since the start of the war in Ukraine, as Russia has pushed for greater effeciency in its economy. While the long New Year holidays remain, most others are now more modest, with often with […] I originally titled this piece “Ghosts of Holidays Past,” way back in 2006. It was an early project I completed for SRAS, written after just three years with the company. Looking back nearly twenty years later, I can see the youthfulness in my writing. While the boundless optimism of that period has been tempered by […] In Russian, New Year is the major celebration of the year. Picture it as Christmas, New Year, and the Fourth of July combined. There are presents, decorated trees, a mythical bearded gift-giver, fireworks, toasts, food, and the grand New Year countdown celebrated at midnight – all associated with this one holiday. Russians are even typically […] Russia and Central Asia offer what can seem to be a bewildering selection of dairy products in their transnational food cultures. An area of special note, and often one of the strangest to Westerners, is the seemingly never-ending assortment of fermented milk drinks and products in the gastronomic repertoire. To cut down on the brow-furrowing […]

The Circus in Russia: Olga’s Blog

Russian Holidays 2026: A Complete Guide

A History of Russian Holiday Ornaments

New Year Holiday Celebrations: Vocabulary and History

The SRAS Guide to Fermented Milk