Dr. Michael Denner: You can tell a lot about a cuisine and culture by the way they eat their milk… That’s the point I tried to make in our latest Georgian Cooking Club meeting, waving about a gallon of milk, sheathed in its translucent plastic carapace. My students were confused at first…

Georgian Milk

Milk. I think a lot about milk when I’m travelling through Georgia. Does any country consume more milk than Georgia?

Milk is an obligatory part of every Georgian table. I’ve never seen a Georgian adult drink milk…. But there are always slices of suluguni, Georgian pasta-fillata cheese (like mozzarella), at every meal. That’s just the beginning… Matsoni, nadugi, chkinti-kveli, girbzhalo, borano… So many basic dishes in the Georgian tradition are riffs that start with fresh cow’s milk.

Milk is an obligatory part of every Georgian table. I’ve never seen a Georgian adult drink milk…. But there are always slices of suluguni, Georgian pasta-fillata cheese (like mozzarella), at every meal. That’s just the beginning… Matsoni, nadugi, chkinti-kveli, girbzhalo, borano… So many basic dishes in the Georgian tradition are riffs that start with fresh cow’s milk.

And anyone who’s travelled to Georgia will tell stories about… cows. They are everywhere. Mostly, though, it seems they spend their lives standing in the middle of the highway, in large herds, distractedly swatting at flies, while you uselessly honk and shout from your stopped car. I’ve seen herds of cows in urban regions, too: right in downtown Zugdidi! And I’ve made way for a lowing herd to pass me while hiking a trail high up in the isolated Mtirala National Park, between the Black Sea and Achara mountain system. I’ve seen them eating grass at the edge of glaciers high in the Caucasus Mountains of Svaneti.

Cows. Everywhere.

Each heifer can produce six or seven gallons of milk per day, while it’s milking. And that milk stays good for, maybe, a day or two without refrigeration. And even with refrigeration, what are you going to do with all that milk in a country with fewer than four million residents, a country famous for its mountain passes and difficult roadways? I don’t know what percentage of Georgian milk is consumed domestically, but I guess nearly all of it. So, obviously, Georgians have devised ways to eat their milk, turning that white liquid into something munchable, using varieties of alchemical wizardry.

The easiest trick for turning milk solid is yogurt, which is really nothing but milk solidified by bacteria and yeast. It happens naturally, with the addition of just a little old yogurt to a gallon of milk and a few hours, a process called “backwashing.” In Georgia, yogurt is called matsoni, and it was Georgia’s most famous contribution to world food cultures during the twentieth century… “In Soviet Georgia” was a Dannon commercial series from the 1970s depicting really old Georgians gobbling up yogurt… These commercials – I remember them well – were largely responsible for the popularization of yogurt in the United States, which until the mid-1970s was a niche product. Why a company founded in Catalonia by a Sephardic Jew and based in Paris was advertising yogurt to America using examples from Soviet Georgia… that’s a story for another time. Suffice it to say, when I was a kid growing up, everyone knew that “in Soviet Georgia” they loved yogurt. But I assure you, they did not eat Dannon. They ate matsoni.

Georgian Cheese

In our latest Georgian Cooking Club meeting here at Stetson University, I demonstrated how easy it is to make cheese by making Imeretian cheese, a cheese from the region Imereti, in central-western Georgia. It is easy: heat milk to about 130 degrees fahrenheit, add a few drops of rennet, wait forty-five minutes, scoop out the curds, drain the curds in the refrigerator for a few days, and you have… Cheese!

Cheese is, essentially, nothing more than curds separated from the whey, using enzymes to coagulate milk solids (fats and proteins). The curds form a solid mass, what in Russian is called “сырная масса” “cheese mass.” The cheese maker cuts them with a long thin knife into manageable pieces, harvests them, and drains away the remaining whey. The whey is just what’s left over: Little Miss Moffet was eating essentially the result and the byproduct of cheesemaking.

Now, here’s where it gets interesting. What do you do with all that whey that’s left over? You boil it and make more cheese! Every cheese making culture has a different word for the product of this second culling… The Italians call it ricotta, which means “recooked,” referring to the second cooking that the whey undergoes. In Russian it’s “творог” (tvorog). In Georgian, it’s nadugi, which means more or less the same things as ricotta: “cooked” or “boiled.” One gallon of milk makes about a pound of fresh cheese, and another cup or two of nadugi.

When we finished making our Imeretian cheese, our Georgian Cooking Club brought the remaining whey to a boil and produced about a cup of nadugi. You just skim the fine curds from the top of the bubbling whey using a spoon. If the whey after this initial boiling remains white, indicating that there are still a lot of “milk solids” left, you can add a tablespoon or two of distilled vinegar to the whey, bring it to a boil again, and harvest the rest of the nadugi that floats to the top.

How And When to Eat Nadugi

In Georgia, nadugi is the king of cold appetizers. It’s sometimes mixed with fresh mint, a combination that was a real revelation for me when I first tried it. It’s often served, a tablespon per serving, wrapped in a cone of thinly-sliced suluguni, another type of Georgian cheese. Imagine a miniature ice cream cone, with the piece of suluguni playing the role of the cone, and the nadugi as ice cream.

My students were reluctant… I mean, mint and cheese? But, trust me, it’s a revelation! For a cup of nadugi, add a heaping tablespoon of finely-chopped mint and a teaspoon of coarse salt. (I like the crunch of salt in the tender texture.) Then, form the nadugi into pretty shapes on plates, as Tina proposes below. (I haven’t tried the orange variation, but I bet it’s lovely.)

Finally, because I wanted to make a point, I made a pile of Russian “блины” (bliny) from the remaining whey: “блины из сыворотки,” blini from whey. Georgians eat bliny all the time, but I believe they think of them as a Russian dish, which makes perfect sense: Georgian foodways are global. Russia has exerted, for better or worse, enormous influence on its smaller neighbor on the other side of the Caucasus.

The recipe for bliny couldn’t be simpler: For every cup of whey, use one egg and one cup of flour. Mix well, add a few pinches of salt, a few pinches of sugar, maybe a big pinch of baking soda if you want… Then make your pancakes! There’s something special about whey-based bliny that makes them better.

So, one gallon of milk yielded us a pound of cheese, a cup of nadugi, and a pile of bliny. That’s how we ate our milk. Enjoy!

The recipe below is my translation and adaption of the recipe in Лобио, сациви, хачапури, или Грузия со вкусом (Lobio, Satsivi, Khatchapuri, or Georgia with Taste) by Tinatin Mzhavanadze.

SRAS: Before moving on to the recipe, I feel the need to interject that, indeed, adults drinking milk is considered an odd thing, it seems, across Eurasia. Although dairy makes up a substantial part of many of the national diets, and although it is common to give kids milk, adults are expected to have grown out of drinking fresh milk and moved on to drinking kefir or any of the fermented milk drinks that Eurasians drink in dizzying variety. The look I’ve often gotten from locals in Eurasia, seeing me drinking straight milk, especially cold from the refrigerator, is similar to the expression you might develop seeing someone eat sour cream with a spoon straight from the container. PS – I’ve seen people here eat sour cream straight from the container…

Tinatin Mzhavanadze Recipe (English)

(as translated and adapted from Russian by Dr. Michael Denner): There’s no competition, I think: The champion of cold appetizers is nadugi. In Georgian, the word means something like “boiled” or “cooked.” nadugi looks a bit like old-fashioned cottage cheese or ricotta: a mass, white as snow, with a mild dairy flavor and slightly grainy texture.

It is, however, not exactly cottage cheese, as it’s a whey-cheese, made from boiling the milky whey that’s left over from cheesemaking, until recently practiced almost universally in home kitchens in Georgia. It is the simplest of milk products, with practically no fat.

Wherever nadugi is sold, you’ll always find thin slices of Georgian suluguni cheese and fresh mint… Mint and nadugi go together like Paris and the Eiffel Tower.

Such a simple, delicious, and versatile appetizer. It’s best served with corncakes (mchadi), or with corn porridge (gomi)… or whatever you like, so long as they are in bite-sized morsels. I’ve been on many diets in my day and nadugi was salve for my soul, especially spread on bread and sprinkled with bran.

From the American Kitchen: While you likely won’t find nadugi outside Georgia, there are a number of perfectly acceptable substitutions, the easiest of which is low-fat ricotta available widely in supermarkets. You can also use homemade yogurt cheese, which has a different texture but a very similar flavor: Line a large, fine strainer with cheesecloth. Add 4 cups of plain, low-fat yogurt, and place the strainer over another bowl to catch the liquid. Refrigerate for 8-10 hours, until reduced by half. (The whey will drain into the second bowl and can be reused.) You should end with about 1 pound.

The suluguni in this preparation is sliced paper thin, and serves mostly as a vehicle to transfer the nadugi to your mouth without the added complication of a utensil… You can really use any mild, white cheese, especially provolone. Ask your deli counter to cut it as thinly as possible.

- 1 pound nadugi or skim-milk ricotta or yogurt cheese (see above)

- 10 very thin slices mozzarella or other mild, white cheese

- 1 small bunch mint roughly chopped (2 1/2 ounces)

- 1 clove garlic, optional

- Small piece of cooked carrot, optional

Serves: 8-10 as an appetizer

At the market, buy a pound of nadugi, ten thin round slices of suluguni, and a bunch of mint. Head home, where you carefully wash the mint, shake it thoroughly dry, and place it on the cutting board. Take out the nadugi and, using a spoon, transfer it to a prep bowl. The last tablespoonful goes straight into your mouth. Now lick your lips with the passion of a gourmand.

Using a sharp chef’s knife, mince the mint finely, rendering it into a fine dust. Add it to your mortar along with a pinch of salt—for what it’s worth, I add a clove of garlic to entice the hungry wolves to the table—and then pound the mix until you have an smooth, even texture. Using a clean spoon or silicone spatula, scrape the mortar clean of all the mint and salt, adding it to the nadugi in the bowl.

The sky’s the limit now. Time for pure, unadulterated creativity. You can…

- Mix the green and white masses together, and end up with a speckled variant;

- Dump the nadugi and mint into the blender jar, and give it a whizz for a few seconds. Your nadugi will have a fine, light consistency, and it will take on the bright, light green of Expressionism, not unlike the green of fresh lettuce;

- If you add a bit of cooked carrot on the blender jar, you’ll end up with an orangish accent… the carrot adds no flavor, just vivacious color.

- You may choose to add some ground black pepper for zing.

I’ve heard some people even add ground walnuts… oh, these days! People have no respect for tradition… And so on. Let’s not go too far. The original, authentic recipe has stood the test of time.

Your nadugi is finished, but your art has only just begun… Here are some ideas: You can place it prettily on little plates and style it into waves, swirling it with the back of a spoon. Or make parallel marks on the surface using a knife, and then decorate it with some sprigs of mint. You can wrap the nadugi in the thin slices of cheese, and then the magic really starts: How about jellyrolls? Or stuffed envelopes? And beggar’s purses, like they serve in fancy restaurants? Tied neatly with a single chive. Very elegant!

SRAS: The above translation and adaptation differs from the original not only in converting the measurements from metric to imperial units (as used by Americans), but also in codifying and more distinctly spelling out the processes that the original author more breezily lays out for an audience more familiar with the food. While giving less instruction, she does give more discussion of variations on the food, for instance. The adaptation by Dr. Denner relies on both the original text and experience traveling to meet the original author and make the recipes with her – making this particular translation and adaptation effort extraordinarily collaborative. We include the original text below for comparison.

Tinatin Mzhavanadze Recipe (Russian)

На мой взгляд, на грузинском столе среди холодных закусок бесспорный чемпион – надуги. В буквальном переводе это слово означает «кипяченый, уверенный».

На вид надуги выглядит, как деревенский творог: белоснежная масса с нежным сливочным вкусом и мелкозернистой текстурой. Однако это не совсем творог, потому что получается он путём кипячения сыворотки, оставшейся от молока после изготовления сыра. Таким образом, это легчайший молочный продукт, в котором почти нет жира.

На вид надуги выглядит, как деревенский творог: белоснежная масса с нежным сливочным вкусом и мелкозернистой текстурой. Однако это не совсем творог, потому что получается он путём кипячения сыворотки, оставшейся от молока после изготовления сыра. Таким образом, это легчайший молочный продукт, в котором почти нет жира.

Произносится слово так: представьте себя парижанином и грассируйте «г» (но ударение все-таки на втором слоге). На любом базаре надуги продается вместе с тонкими лепешками сулугуни и свежей мятой: мята и надуги неразделимы, как Париж и Эйфелева башня. Вы покупаете полкилограмма надуги, штук десять сырных лепешек (это сулугуни, только сделанный в один слой толщиной в полимиллиметра), пучок мяты и топаете домой.

Там вы тщательно моете зелень, встряхиваете, кладёте на доску для нарезания, потом вытаскиваете надуги, задумчиво перекладываете его из пакета ложкой в миску, последнюю полную ложку отправляете в рот и облизываете со всем пылом гурмана.

Острым ножичком кромсаете в пыль мяту, пересыпаете её в ступку и добавляете крошечку соли (я, к примеру, добавляю ещё зубчик чеснока – для дополнительного возбуждения и без того волчьего аппетита), потом толчёте и растираете до получения однородной кашицы.

Ингредиенты:

(на 10 порций): надуги (или рикотта, или нежирный творог) – 0,5 кг лепёшки сулугуни – 10 шт. (по желанию), мята – пучок, соль, чеснок – по вкусу

Берёте чистую ложку, выскребаете из ступки мяту с солью и вмешиваете в надуги.

Далее открывается простор для чистого, незамутнённого корыстью искусства:

- вы можете экспрессивно перемешать зелень с белой массой и получить вариант в крапинку;

- вы можете смешать их в блендере до ровного салатового оттенка – в духе импрессионисто;

- вы можете добавить оранжевые акценты с помощью кусочков отваренной моркови – вкуса никакого, зато сколько живости!

- вы даже можете сыпануть молотого чёрного перца для готичности.

Я слышала, что в надуги даже вмешивают молодые грецкие орехи – о времена! О нравы! Ну и так далее – но слишком далеко от оригинала тоже отходить не стоит.

Так вот, надуговая (или надужья) масса готова, но творчество продолжается.

Можно красиво выложить его на маленькие тарелочки и сделать волны ложкой или насечки ножом и украсить веточкой мяты, а можно завернуть в салфеточки-сулугуни! И как завернуть – о господа, это чистая радость дизайнера!

И рулетиком! И конвертиком! И котомочкой!

И перевязать пёрышком лука-резанца – изящно и кокетливо.

Вы посмотрите, что за красота!

Лёгкая, аппетитная, эстетичная холодная закуска, которую полагается есть либо с мчади, либо с гоми, либо как хотите – хоть целиком отправляя в рот. Во время нескончаемых диет надуги – услада моей души: особенно намазанный на хлеб с отрубями на завтрак.

Специалисты говорят, что итальянская рикотта концептуально изготавливается так же, как надуги.

Если в пределах досягаемости нет надуги, возьмите молоко и кальций и створожьте сами, чего уж там.

Хотя есть очень простой способ получить похожий по вкусу продукт, даже ещё более нежный: надо взять свежее мацони – примерно пол-литра, налить в чистую марлечку и подвесить котомкой стекать на ночь над миской.

Our Favorite Nadugi Videos

A clear video in Russian.

You Might Also Like

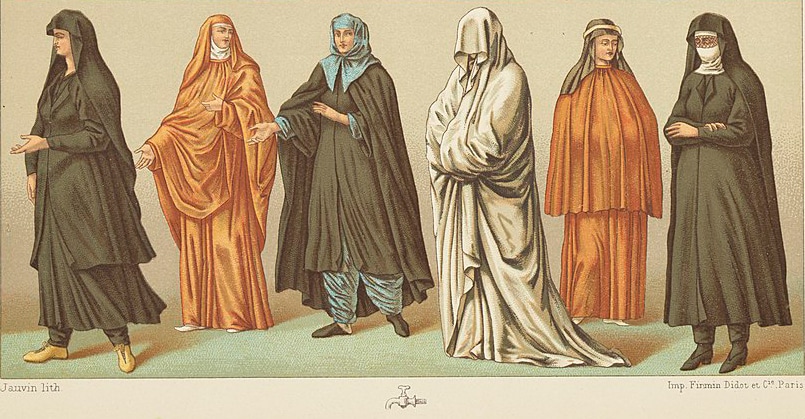

The Talking Phrasebook Series presents useful phrases and words in side-by-side translation and with audio files specifically geared to help students work on listening skills and pronunciation. Each entry below, divided by category, features an English word or phrase in the left column and its Georgian translation in the right. The Georgian is presented in […] Georgian holidays strongly reflect the country’s unique traditions and its demographics. First, as more than 80% of Georgians identify with the Georgian Orthodox Church, the strong influence of the church can be felt in the preponderance of Orthodox holidays. Georgia also has several holidays celebrating its statehood and independence, which have been hard-won. We can […] Fruit leather is simple, ancient food. Like bread and roasted meat, it likely independently evolved in several places. At its most basic, it is simply mashed fruit smeared to a sheet and left to dry in the sun. The result is a flavor-intensive food that travels well and can keep for months. The oldest known […] This guide to travel in Georgia is tailored for Jewish-American university students preparing to study abroad in Georgia. We navigate the historical depth and modern vibrancy of Jewish life in this culturally rich country. Discover key historical sites, engage with local Jewish communities, and find practical tips on maintaining kosher practices and observing Shabbat while […] Despite their cloistered livelihood, nuns have found their way into many veins of popular theater and movies. However, their usual depiction, wearing black habits with a veil and carrying a rosary, is not accurate for all nuns. It is true that the symbolic meaning of the habit is consistent across both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox […]

The Talking Georgian Phrasebook

Georgian Holidays 2025: A Complete Guide

Tklapi, Pastegh, Lavashak: One Ingredient Fruit Leather from the Caucasus

Jewish Georgia: A Brief History and Guide

The Habits of Nuns in Catholic and Orthodox Traditions