Russia and Eurasia offer what can seem to be a bewildering selection of dairy products in their transnational food cultures. An area of special note, and often one of the strangest to Westerners, is the seemingly never-ending assortment of fermented milk drinks in the Russian gastronomic repertoire. To cut down on the brow-furrowing and sometimes taste-bud-curdling excursions to your local Russian store, we’ve produced the following short but fairly comprehensive guide to the Russian fermented milk market.

Prostokvasha

(Простокваша)

To start, it is probably most instructive to begin with prostokvasha. Prostokvasha is actually not one product, but rather a blanket term for a variety of fermented milk products that, as the Russian “просто” (simple) implies, are quite simple to ferment, which is what the “кваша” portion of the name refers to: “сквашивание” (souring or fermenting).

The simplest prostokvasha is made simply by allowing milk to sour in a warm place. However, this can be dangerous, as the fermenting microbes in this case come from the atmosphere and can therefore contain any bacteria, even harmful ones. Without regulating the bacteria or the souring process, the taste of the final product is also hit-or-miss. Therefore, most milk products considered prostokvasha are made by first boiling whole or otherwise unprocessed milk and then heating it for several hours (4-8) while adding selected cultures. Prostokvasha is mostly used for drinking, often for its healthful dietary properties: healthy bacteria can improve digestion and dairy fats provide a good source of energy.

Kefir

(Кефир)

Kefir is probably the most widely-known of Russia’s fermented milk drinks. Кефир is drunk throughout Eastern and Northern Europe, but has also been popular in South America since immigration from the former Ottoman Empire and Eastern Europe carried it there. Kefir has also been introduced to the wider Western world in recent years as globalization continues and scientific research has shown kefir to have several health benefits.

The name “kefir” comes from the Turkish köpür, a variant of the word for foam. This is an apt name, as the drink itself is carbonated from the fermentation process. Fermentation also gives the drink small amounts of alcohol, usually ranging from 0.5 to 1%. The alcohol content, however, can range from 0.06 to nearly 3%, with higher levels occurring when the container is airtight, shaken more frequently during fermentation, and with longer fermentation periods.

Kefir has the consistency of a thin yogurt with a sour taste (the intensity of which is also directly correlated with the length of fermentation).

Kefir is traditionally made by fermenting milk (of any kind, including soy) with “кефирные зерна” (kefir grains). These are symbiotic cultures of yeasts and bacteria encapsulated in a shell of fats, proteins, and sugars. The practice of making them began with shepherds in the northern areas of the Caucasus, who, upon discovering that the milk they carried with them would often ferment into a frothy, yummy mixture, began to create the drink intentionally by isolating the grains that were responsible for the fermentation and adding them to batches of milk. So, the process is not unlike making sourdough bread, where pieces of dough are kept to ferment the next batch with the same microbes – in this case, those common to the Caucasus Mountains. You can buy кефирные зерна on Amazon.

Eventually, production of kefir left the shepherd’s pouch, and today the homemade version calls for any loosely covered container able to withstand the acids of fermentation. The milk and kefir grains are introduced into the container, leaving some space at the top for the expansion of the liquid created by the chemical reactions that will take place, and stored in a dark, room-temperature environment. After about 24 hours, during which one must shake the container at least once, the kefir mixture is ready for the final step – sieving out the kefir grains. These grains, which actually grow during the fermentation process, can then be extracted and used to make fresh batches of kefir and can even be sold (unless you are a Caucasian shepherd, it is very unlikely that you have the preconditions necessary to generate kefir grains on your own; you must buy your first grains).

Russians often take production of kefir to a second stage by introducing the mixture produced from the first phase into a separate batch of fresh milk and letting this new combination sit for another 12 to 18 hours. This allows for a larger, evenly fermented batch with a slightly stronger flavor, but also allows the grains to be harvested before adding flavoring such as lemon or sugar, which can make a more flavorful product, but which can, in some cases, harm the precious grains.

Modern, mass-produced кефир, by the way, does not actually use grains anymore. Instead, a scientifically precise mix of bacteria and yeasts are used in order to maintain uniform consistency and flavor.

Regardless of its method of production, kefir can be enjoyed as a beverage or used in cooking (it is an especially good substitute for buttermilk). Some prefer to set newly-made кефир aside for a while in order to allow further thickening and souring of the mixture. Beware, however, as the unrefrigerated lifespan of kefir is only two to three days.

Toplenoe Moloko

(Топлёное Молоко)

This next milk product is actually not fermented, however it is found in the same store section as its brewed brethren and is the basis for another fermented milk product, ryazhenka (see below). Toplenoe moloko, often rendered in English as “baked milk” is not quite what its common translation suggests. The persistence of the bad translation is perhaps not surprising as it is not a drink well-known outside of Slavic countries. Топленое literally means “rendered” or “clarified,” and in fact “clarified milk” gives one a much better understanding of the actual nature of the product, as топленое молоко is made from whole milk that has been boiled and heated in much the same way as clarified butter; the heating process allows the separation and evaporation of water and some milk fats.

Though toplenoe moloko is made industrially through a somewhat complicated process involving pasteurization and constant stirring and skimming, it is really quite simple to make at home. The creamy, caramel-tasting, beige-colored drink has been traditionally made in Slavic countries for centuries using the traditional “Russian” oven, which is extremely well-suited to the task due to its renowned ability to evenly distribute heat.

The first step is to boil whole milk. Then the milk must go through a period of strong, even heating, preferably as hot as one might achieve without inducing the milk to boil again. There are two general ways of doing this: 1) pour the boiled milk into a thermos that has been rinsed out with very hot water and let it sit for 4-6 hours, or 2) heat the milk externally in a closed dish for no less than an hour and a half.

There are potential pitfalls to either method; making топленое молоко the first way requires a truly well-sealed and heat-retaining thermos, otherwise the whole process will be for naught, and making it the second way runs the risk, if the heat is not even, of either evaporating the milk or destroying some of the proteins that give the treat its special taste.

What gives toplenoe moloko its special taste and coloring properties are the chemical interactions between the sugars and amino acids in whole milk that result from long heating (but not boiling). These interactions produce compounds called melanoidins, which are brown and quite weighty by molecular standards, giving toplenoe moloko its beige color and creamy texture. Also, because of these chemical reactions, the product preserves very well and can be kept at room temperature for up to five days, much longer than milk at either of its previous stages – whole and boiled. Although it is mostly saved for drinking, toplenoe moloko also has uses in cooking, such as baking “пироги” (Russian equivalent of turnovers) or making creams and sauces. It can also be fermented to make another Russian treat – ryazhenka.

Ryazhenka

(Ряженка)

Ryazhenka is basically fermented toplenoe moloko, and in taste and texture is very much like unsweetened yogurt. Its origins are likely in the lands that now comprise Ukraine, where it has long been a staple of civilization there. It was originally made in special earthenware pots called “глечик” (glechik), in which milk and cream would be heated until they lost the beige color characteristic of toplenoe moloko. Then, as is still done today when making homemade ryazhenka, a bit of sour cream would be added to the mix and it would be set aside to ferment for 3-6 hours.

This process differs a bit from industrially made ryazhenka, in which fermentation is induced through the addition of thermophilic streptococci bacteria and cultures of Lactobacillus bulgaricus, a bacteria widely used in making yogurt. By the end of fermentation, ryazhenka gains a brownish-yellow color and the sharp, sour taste of most fermented milk products.

Snezhok

(Снежок)

Source: www.100best.ru

Snezhok is essentially very sweet prostokvasha, created by heating sterilized milk with the addition of the same bacteria used to make ryazhenka and sour cream. To complete snezhok, however, generous amounts of sugar and/or berry-flavored fruit syrups are then added. As such, this is one of the more popular fermented milk products among children, and is a favorite among all ages for breakfast. This may also help explain its rather cute name; “snezhok” means “snowball,” and is so named because the end product, so long as only white sugar is added, is as white as snow.

Tan

(Тан)

Tan is not Russian – but is well-known in Russia and widely available there. Originally an Armenian drink, it can be made with either cow or goat milk. It is made with same bacteria as sour cream and ryazhenka, but also adds lactose-fermenting yeast to the mix. The final difference from a traditionally Slavic prostokvasha like ryazhenka is the addition of salt, and often salt water, making it nearly the polar opposite of snezhok!

The popularity of tan in Central Asia and the Slavic countries into which it has infiltrated is only increased by the fact that the drink has a unique combination of health benefits due to the nutrients provided by the salt addition and their interactions with the very biochemically active fermenting agents. It is widely used as a cure of an upset stomach and is a popular hangover cure.

Kumys

(Кумыс)

Kumys is actually Central Asian in origin, but is not unknown in Russia and is perhaps just too cool to pass up in our discussion of fermented milk.

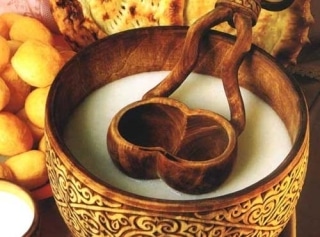

Kumys is traditionally made from horse milk. It is drunk widely among the tribes of the Central Asian steppes. In fact, its importance to Kyrgyz history can be seen in the fact that Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, is named for the spoon used to churn kumys as it ferments. The name “kumys” probably comes from the name of the Turkic peoples called Kumyks (a major ethnic group in modern-day Dagestan and Northern Ossetia). Like the Turkic peoples of Central Asia, kumys is ancient, with references to the drink in the Greek historian Herodotus’ famous 5th century BCE work, The Histories.

Like tan, kumys is made using yeast as well as cultures of Lactobacillus bulgaricus. However, the process for making kumys is more akin to making butter than to making prostokvasha; unpasteurized mare’s milk and bacterial agents are mixed and left to ferment, and are often stirred and churned to ensure the progression and evenness of the fermentation process. In earlier times, kumys was often strapped to the saddles of the nomadic steppes tribesman so that the movement of horses could do the work of agitation. Another method utilized was to hang skins partially filled with the pre-kumys mixture on the doors of houses, and passersby, knowing what these skins signaled, would give them a good punch to ensure continued successful fermentation.

In the modern day, mare’s milk is a scarce commodity, even where kumys is popular, so industrial production of the drink often uses cow’s milk fortified with extra sugars, in order to simulate the amount of fermentation sugars produced by the higher lactose concentration in mare’s milk.

Kumys has a light but sour flavor, emphasized by the bite of the alcohol it contains. Kumys typically has more alcohol than any of the products discussed here (usually 1 – 2.5%). This is due to the higher sugar content in mare’s milk and the constant agitation of the fermenting mixture. Comparable to a regional beer, kumys is mostly served cold or chilled in small bowl-like, handle-less cups called pivala, and is an essential part of Kyrgyz guest-right rituals. It is traditional at the end of each kumys-sipping session to pour the dregs from one’s pivala back into the container holding the reserves of kumys in order to waste nothing and ensure that your hostess has enough remaining for guests yet to come.

Fermentation for Preservation and Taste!

Clearly, fermented milk is a big deal in Russia and the surrounding areas… a really big deal! While there is no definitive answer as to exactly why this maybe, a key to the puzzle most likely lies in the fact that fermentation, like pickling or salting, is just another means of preservation. In times before commercial refrigeration, when most were living at a subsistence level, one had to keep produce as long as one could to reap its benefits to the fullest. The fermentation of milk can add a few days to the shelf life of milk by at least controlling the natural fermentation process that will naturally occur.

Slightly spoiled ryazhenka or kefir can also still be used to make baked products like “пироги” (stuffed pies) and “блины” (bliny). Some say these slightly spoiled products, in fact, make the best versions of these traditional dishes, as the carbonation can make for a very light and fluffy dough while the baking process kills the bacteria present.

For many Westerners, most fermented milk products will be an acquired taste to say the least. For starters, though, maybe go with some toplenoe moloko, which, as you now know, is not actually fermented and has a rich, caramel taste. If you like that, why not dip both feet in and try some snezhok, which is nice and sweet and probably the mildest introduction to actual fermentation? Keep building up your tolerance and branching out, and soon you may join the ranks the Russians as a lover of fermented milk!

Our Favorite Fermented Milk Videos

Video about the industrial production and health benefits of kumys.

Video investigating the production and properties of a well-made snezhok and providing a recipe for “оладушки” made from this product.

You Might Also Like

Kupala is an ancient Slavic holiday celebrating the summer solstice, or midsummer. Once part of a series of annual rituals, it marked and was believed to sustain agricultural cycles—essential to early human survival. Held as vitally important, these pagan traditions remained deeply rooted even after Christianization, technological change, and centuries of oppression tried to dislodge […] Easter breads such as kulich, paska, choreg, and nazuki are delicious Easter traditions. Easter is by far the most important religious holiday for those practicing Eastern Christianity. In addition to church services and egg dying, the holiday is also marked across the cultures by ritual bread baking. Despite the wide geographic area covered by Eastern […] Below, Tajik blogger Roxana Burkhanova describes, in Russian, the place of St. Petersburg in Russian culture. She discusses the city’s history as well as its literary heritage, its nightlife, and even how people from Petersburg speak their own, slightly different dialect of Russian. The text was originally written in 2015 and thus references times before […] Rites of welcoming spring and saying goodbye to winter are some of the oldest holidays preserved across Slavic cultures. In the Baltics, the celebrations were nearly lost after being suppressed by Catholic and imperial dominance. Today, Russia’s Maslenitsa is by the far the best-known, but multiple versions exist across the diverse Slavic landscape. In the […] This extensive list of web resources to assist students learning the Russian language was developed by SRAS and is now hosted on Folkways, part of the SRAS Family of Sites! Disclosure: Some of the links below are affiliate links. This means that, at zero cost to you, we will earn an affiliate commission if you […]

Kupala: Ancient Slavic Midsummer Mythology and its Modern Celebration

Kulich, Paska, Nazuki: The Easter Breads of Eastern Christianity

Off to Petersburg, Russia’s Cultural Capital: Моя Россия Blog

Maslenitsa, Masliana, Meteņi: Spring Holidays of the Slavs and Balts

Resources for Students of Russian