Dr. Michael Denner: It would be difficult to imagine Georgia without maize, what Americans call corn, though of course corn came from South America, and could only have been introduced to Georgia after Columbus brought it back from the New World… so in the sixteenth century at the earliest.

Mchadi and Corn In Georgia

My friend and cookbook collaborator Tina Mzhavanadze, jokes that, Georgians being Georgians, they all believe that corn originated in Georgia. There’s also a version of food history that proposes that corn came to Georgia earlier than to the rest of Europe, via China early in the sixteenth century… I doubt its veracity, but  who knows? In the sixteenth century, Georgia belonged to the Persian empire of the Safavids, and was far removed from Western European influences and trade routes. I could maybe imagine a Ming merchant wandering across Transoxiana and the Caucasus, sowing corn like Johnny Appleseed…

who knows? In the sixteenth century, Georgia belonged to the Persian empire of the Safavids, and was far removed from Western European influences and trade routes. I could maybe imagine a Ming merchant wandering across Transoxiana and the Caucasus, sowing corn like Johnny Appleseed…

There’s a line somewhere through the middle of Georgia, not too far from Tbilisi, that divides the “corn belt” from the “wheat belt.” West of the line, it’s hot and rainy, especially in Imereti and Samegrelo. Corn grows everywhere there, and the everyday bread is mchadi, skillet-cooked corn muffins. East of the line, the climate turns more austere, sterner, drier: The perfect climate for wheat, and so poori, Georgian “lavash” bread made from wheat, finds its place on the plate.

Georgians will tell you that authentic, real mchadi are only made from cornmeal and water, and are fried in a large dried cast-iron skillet, or better yet, in a k’etsi, a micaceous earthenware cooking vessel. Maybe. In the homes and restaurants where I’ve had mchadi, they’ve always been “modern” mchadi, with salt, sugar, some baking soda, and fried in oil. In any case, mchadi are the classic accompaniment to lobio, bean soup: you break the mchadi into pieces and sprinkle it over the top of the lobio, quickly spoon the mix into your mouth, chew thoughtfully, and wash it down with some Georgian white wine. Yum!

With my students here at Stetson, we prepared the first recipe below, “modern mchadi.” I was introducing my students to Georgian cooking, and I wanted to make several points, including the idea that Georgian cuisine was international. Exhibit A was the New World corn, without which contemporary Georgian cooking would be unthinkable. But Georgia is also multiethnic, and shares a heritage of cooking with the other nations of the Caucasus, Armenia and Azerbaijan. About five percent of the Georgian population self-identifies as Armenian; mostly the Armenians live in Samtskhe-Javakheti, in the south of Georgia near the Armenian border. Historically, though, Armenians have represented a much larger proportion of the population of Georgia. Therefore, to accompany our mchadi, I served Armenian tan, a drink made from yogurt thinned with water and the addition of salt, very similar to ayran, the Turkish national drink. Southerners will comfortably recognize its kindredness with buttermilk.

We also drank green tea grown in Batumi, near the Turkish border.

As a southerner, I admit to liking my cornbread slightly sweet and salty. I’ve made the recipe with and without baking soda, and could not decide which I prefer. For oil, as always I recommend a mix of toasted sunflower seed oil mixed with a neutral vegetable oil, which closely approximates the unrefined sunflower oil used in Georgia. Olive oil would overwhelm the subtle flavor of these cakes.

These recipes are my translation and adaption of recipes in Лобио, сациви, хачапури, или Грузия со вкусом (Lobio, Satsivi, Khatchapuri, or Georgia with Taste) by Tinatin Mzhavanadze.

Modern Mchadi

| Tinatin Mzhavanadze (as translated and adapted from the Russian by Dr. Michael Denner): | Tinatin Mzhavanadze (original text): |

| As a small child, I didn’t care for mchadi, Georgian cornbread… Can you imagine? My grandmother, on the other hand, always ate mchadi. She made the simplest type, just cornmeal and water, cooked on a dry skillet. She always served them with cheese, preferably the firm and ripe kind we called “factory” cheese… it was dense, slightly salty, and had a yellowish color. And she always served it with a lot of fresh green herbs.

Or she served mchadi with smoked fish. Anyway, later in life I understood the “secret” taste of mchadi. When I moved far-far away from home, and became heartsick for the flavors of your motherland… It was the fresh, clean taste of of cornbread that I missed: It’s the perfect foil for salty and spicy flavors. The flavor of mchadi embraces them, and lends a bit of its ascetic nobility. That said, you can also make a much lighter variety of mchadi with the addition of a bit of baking soda and milk, appropriate when you want to try out a recipe for the first time. Ingredients: (serves 4-6, making 12-15 small cakes)

Preparation

|

В глубоком детстве я не любила кукурузный хлеб, представляете? А бабушка ела только мчади, причем пекла самые простые – мука и вода, на сухой сковородке, только обязательно нужен был сыр – лучше, конечно, зрелый, который называют «заводским» — плотный, солоноватый, с желтизной. И много свежей зелени.

Или с копчёной рыбой, например. Это потом я поняла секрет вкуса мчади — когда уехала далеко-далеко от дома и соскучилась по родной еде: пресный на первый взгляд вкус кукурузных лепешек – как загрунтованный холст для ярких соленых и острых кушаний, он раскрывает их и оттеняет своим аскетическим благородством. А пока можно сделать гораздо более «мягкий» вариант мчади, пригодный для того, чтобы распробовать непривычный вкус, — надо прежде всего взять белой кукурузной муки тонкого помола и просеять в миску. Ингредиенты: (на 12-15 маленьких лепешек или 1 большую)

Приготовление

Можно есть с чем хотите, но мой вам совет – холодная жареная рыба, камбала к примеру, и свежая зелень. И запивайте чаем. Впрочем, можно и белым вином.

|

Traditional Mchadi Recipe (Russian)

(Мчади: традиционный рецепт)

Но раз уж мы рассматриваем все возможные варианты, давайте я вам расскажу про совсем простой, деревенский мчади – как его делает моя мама.

На слабый огонь ставится большая толстенная сковородка и долго-долго греется, пока от капли воды не полетят брызги.

Тем временем просеянная кукурузная мука заливается в миске теплой водой и месится.

Месится-месится, долго и тщательно, пока тесто не будет одним большим шаром. Тут важно угадать степень его влажности: если воды меньше, мчади потрескается, если больше – развалится на куски. А раз мука кукурузная, подсказать консистенцию трудновато – не знаю, с чем сравнивать. Оно не жидкое – это совершенно точно, ближе к глине, готовой для изготовления кувшина – вот!

Итак, сковорода нагрелась, тесто готово: теперь этот кругляш надо аккуратно выложить на прокалившуюся поверхность и мокрыми руками «растоптать» в толстый, сантиметров пять, ровный блин, но лучше между лепешкой и бортами сковородки оставить хоть миллиметр зазора.

Огонь пусть будет по-прежнему маленький, но не совсем сдыхающий, и пусть одна сторона печётся с открытой крышкой минут двадцать, а то и полчаса. Когда верхняя поверхность подсохнет, а внизу образуется корочка, легко отстающая от сковороды, — можно переворачивать.

О, это целое искусство! Даже опытная хозяйка может споткнуться и разломать блин – что уже говорить о салагах. Мама как-то хватает этот огнедышащий краешек пальцами и – хоп! – он уже перевернут. Не переживайте: я беру длинный плоский нож, подвожу снизу, другой рукой придерживаю салфеткой горячий край и, пыхтя, провожу операцию «кувырок» вполне сносно.

Вторая сторона тоже должна пропечься до толстой корочки – теперь можно и задвинуть крышку на некоторое время, для пропарки.

Ну что, пришло время вынимать наше солнышко-мчади? На столе уже есть сыр, толстый омлет с сыром – борано и красная капуста. Можно и копченой ветчины отварить, и вино поставить. Да, еще с хамсой, тушеной в листьях, — неповторимо.

Тогда вываливаете круг кукурузной лепешки на полотенце, пусть отдышится минут пять – и можно ломать на куски.

Для особо светских – режьте ножом, так и быть.

А есть еще сванский вариант, чвиштари называется: похоже на обычные маленькие мчади, жареные на масле, но внутрь кладется брусочек сулугуни, и получаются кукурузные хачапури.

А еще можно пофантазировать: вмесить в тесто тертый сыр, мелко нарезанную мяту, немного тархуна или специй…

Traditional Mchadi Recipe (English)

SRAS: Although the original cookbook contains only the discussion on “modern mchadi,” Dr. Denner plans to include a second section devoted to a more traditional recipe he learned from the cookbook author while in Georgia. That recipe follows.

Dr. Denner: So long as we’re on the subject of mchadi and their variations… I’ll share a recipe for the simple mchadi they make in rural Georgia, the kind Tina’s mother made.

Dr. Denner: So long as we’re on the subject of mchadi and their variations… I’ll share a recipe for the simple mchadi they make in rural Georgia, the kind Tina’s mother made.

Tinatin Mzhavanadze (as translated and adapted from Russian by Dr. Michael Denner): Place a large, heavy cast-iron skillet on very low heat, and let it heat for a very long time, until a drop of water jumps and skates across it surface. Do not add oil! Sift around a pound of cornmeal into a large bowl, and in the microwave or in a small pan, heat 8 ounces water until warm, about 105*. The water should be warm to the touch.

While the skillet is heating, mix the sieved cornmeal with warm water in a large bowl. Knead it a very long time until it becomes a smooth ball. You’ll know if you’ve added too little water if the mass is shaggy, and if there’s too much water, the ball won’t come together and will come apart in little pieces. It’s hard to specify how the dough should feel, as this is cornmeal (which varies greatly depending on the corn itself, how it’s ground, how long it’s been stored, and so on). The dough shouldn’t be wet, that’s for sure… it’s like the consistency of clay that you’ve prepared for making pottery. Like in so many things, experience is your best guide…

So, your skillet is hot and the dough is ready. Now, carefully take that ball of dough and place it on the heated surface of the skillet, and with moistened hands, pat it out into an even cake, about 2 inches thick. Ideally, the cake should cover most of the surface of the skillet, practically to the edges of the skillet if you’re using one.

Keep the flame under the skillet very low, and let the corncake bake slowly, uncovered, for 20 to 30 minutes. You’ll know it’s done on the first side when the exposed side begins to dry out a bit and on the underneath has turned golden brown. Now, you need to flip it.

This cake flipping, it’s an art! Even an experienced cook can make a mess of it, breaking the cake in two, and when you’re a rookie… My mom just reached under the cake with her bare fingers, the hot surface notwithstanding, and… POP!… the cake was flipped. Keep your wits! Here’s how I do it: I take a long flat knife or offset spatula, slide it under the cake, and with my other hand I use a napkin to hold onto the hot cake from above, with an even and smooth motion I execute a “somersault” operation on the cake.

The second side should cook until it, too, is golden brown and crusty… Once it’s browned, put the top on the skillet and let it steam a bit, for 5 minutes.

Flip the mchadi into a clean kitchen towel, fold the edges of the towel over it, and let the mchadi rest and cool a bit. To serve, break the mchadi into pieces by hand. (I suppose if you want to be all city about it, you can use a knife.)

Serving time! Whether it’s modern or old-fashioned mchadi, on the table with your corncakes, you’ve got some cheese, a fat leek omelet, maybe a borano (a traditional Georgian cheese omelet), and some fermented red cabbage. Perhaps a bottle of red wine. A perfect Georgian vegetarian meal.

Come to think of it, there’s a Svann version of this dish, prepared in the Caucasus Mountains in the north of Georgia, where they’re called chvishtari. Make small mchadi using the above method, dividing the dough into pieces about the size of walnuts. Flatten the balls, and stick a very small piece of suluguni or fresh mozzarella inside. Fold the dough over the cheese and pat the mchadi flat. Fry them in butter… and you get cornmeal khatchapuri! Or we could make some fantasy mchadi, perhaps kneading grated cheese and finely minced mint into the dough, perhaps a little tarragon or some Georgian spices, too…

Our Favorite Mchadi Videos

A beautiful video in English showing Mchadi being made (and then stuffed with cheese).

You Might Also Like

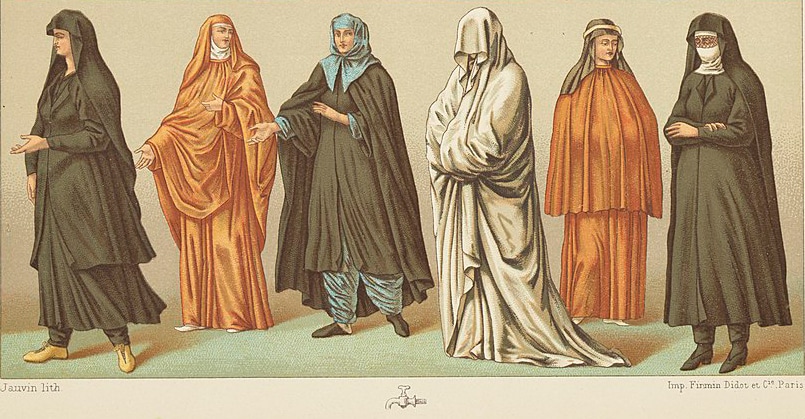

The Talking Phrasebook Series presents useful phrases and words in side-by-side translation and with audio files specifically geared to help students work on listening skills and pronunciation. Each entry below, divided by category, features an English word or phrase in the left column and its Georgian translation in the right. The Georgian is presented in […] Georgian holidays strongly reflect the country’s unique traditions and its demographics. First, as more than 80% of Georgians identify with the Georgian Orthodox Church, the strong influence of the church can be felt in the preponderance of Orthodox holidays. Georgia also has several holidays celebrating its statehood and independence, which have been hard-won. We can […] Fruit leather is simple, ancient food. Like bread and roasted meat, it likely independently evolved in several places. At its most basic, it is simply mashed fruit smeared to a sheet and left to dry in the sun. The result is a flavor-intensive food that travels well and can keep for months. The oldest known […] This guide to travel in Georgia is tailored for Jewish-American university students preparing to study abroad in Georgia. We navigate the historical depth and modern vibrancy of Jewish life in this culturally rich country. Discover key historical sites, engage with local Jewish communities, and find practical tips on maintaining kosher practices and observing Shabbat while […] Despite their cloistered livelihood, nuns have found their way into many veins of popular theater and movies. However, their usual depiction, wearing black habits with a veil and carrying a rosary, is not accurate for all nuns. It is true that the symbolic meaning of the habit is consistent across both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox […]

The Talking Georgian Phrasebook

Georgian Holidays 2025: A Complete Guide

Tklapi, Pastegh, Lavashak: One Ingredient Fruit Leather from the Caucasus

Jewish Georgia: A Brief History and Guide

The Habits of Nuns in Catholic and Orthodox Traditions