There are few essential things to know about Kyrgyzstan. One of these is the country’s folkloric hero, Manas. You’ll find nearly everything in Krygyzstan is named after him: the main airport, national parks, major streets in nearly every city and town, and even karate clubs and movie theaters, not to mention the statues of him in just about every town big enough to have placed a statue of any kind.

Manas is Kyrgyzstan’s literary and spiritual hero. He is a foundational figure in Kyrgyzstan’s national narrative. He is a man known for courageously fighting against external foes and reuniting the 40 tribes of the Kyrgyz people. He is also the ultimate symbol of Kyrgyz cultural identity, which is expressed all over Bishkek, from his looming statue in Bishkek’s central square, to his image plastered on Coca Cola billboards. Just how big a hero are we talking about? Put it this way. The Manas epic poem, which has more than 80 versions and has been translated into more than 39 languages, is the longest epic poem in the world. At close to half a million lines, it is 20 times longer than the Odyssey and the Illiad combined. Welcome to Kyrgyzstan; Welcome to the Land of Manas.

The Origins and History of the Manas Text

Now, like that of Odysseus, Hercules, or Paul Bunyan, the true existence of Manas is not entirely certain. Like most myths, stories of him may have been originally based on fact, then got elevated to larger-than-life, legendary status after a few centuries of storytelling. In Kygyzstan, this storytelling is the realm of highly trained manaschi, bards who have dedicated themselves to memorizing almost innumberable lines and chanting the verses of his story.

The stories themselves may have originated a millenia ago. Traditions of manaschi passing the tales down as a cultural institution likely began in the 16th century. This was well after the man, if real, was long dead, and before writing came to Kyrgyzstan. The first to actually begin to write the epic down were actually Russian ethnographers who arrived in the 19th century. Since then, it has been written down more than sixty times from various bards, creating a different version each time.

Although translated on several occasions many translations have not been based on the original Kyrgyz, but rather relied on Russian translations. These, many say, distort the original meaning. Only in 2005 did a scholar from Kyrgyzstan, Elmira Köçümkulkïz, then a Ph.D Canidate at the Univeristy of Washington, produce the first English translation of a few excerpts of the original Kyrgyz text. She used recordings from Saiakbay Karalaev, a manaschi that lived from 1894 to 1971 and is now regarded as the best manaschi of our time and possibly of all time. The text is available for free online and likely holds truest to the original meaning, although the poetic qualities of the language are largely lost in the non-native English translation.

The Epic of Manas in World Literature Context

Manas is a hero of supernatural strength who united the forty clans of Kyrgyzstan against their enemies, the Uyghers, to build a Kyrgyz state. At the time, in the early 9th century AD, the Uyghers held one of the world’s great empires spanning much of Central Asia (including Kyrgyzstan), Mongolia, and parts of Russia and China.

The poem begins with the ancestry and birth of the hero, which is first prophesied and surrounded by unusual portents. His father, an aging though wealthy and generous leader of his people, is without a son or heir. He visits a holy place, prays for a son and soon after his wife becomes pregnant. She develops cravings for tiger meat. The proud father-to-be spares no effort getting it. Care is taken to keep the pregnancy a secret from the Uyghers as it is feared that the Kyrgyz heir might be targeted while still in the womb for political reasons. All the while, wise men describe the deeds Manas will accomplish and the armies he will lead. When he is born, he leaps from the womb and lands on his feet, ready to fight those who would stand against him and threaten his people.

The epic continues, like most epics do, with a rousing and fantastic adventure story. The poetic language, with its rhythm, repetition, and dramatic foreshadowing of coming events, is meant to draw the reader into the story and feel as if they were there themselves. The poetry is reasonably complex: each line is seven to eight syllables, with end rhyme and internal alliteration.

The birth of Manas has much in common with some western heroes. Hercules was also born with super-human strength, partly received from his father, the god Zeus, and partly from being suckled by a goddess. Manas, it is implied, seems to have gotten some of his strength from the tiger meat eaten by his mother. John, the great biblical prophet, was born to an aging father who showed piety in a holy place. Moses was born fated to unite his people and lead them to freedom. Manas too is born after his aging father prays in a holy place, fated to become a legendary leader and defeat the enemy that surrounds him.

Part of Manas’ strength is drawn from the animal spirits protecting him: there is a lion at his side and a giant hawk flying overhead. This gives the tale an eastern flavor and even draws some similarities to many Native American myths.

Another trope shared with world literature is that the story rotates through cycles of death and rebirth, a motif common to all the world’s cultures, as Joseph Campbell’s The Power of Myth. Manas traces its story across three generations (Manas, his son, and grandson); at the end of each episode, save the last, the hero dies, his kingdom is destroyed, and his young son is left to grow up and rebuild. In one version of the tale, sung by a bard in western China, the process is traced through seventeen generations.

Real or not, Manas defines the Kyrgyz spirit. Today, Kyrgyz people still say to each other, “I wish the soul of Manas to protect you” when they want to wish each other well.

Performing Manas: The Ancient Craft of the Manaschi

Manas has long been recited by professional bards. Originally, they were known as jomokchu (from the Kyrgyz “jomok,” or “tale”). Today they are known as manaschi (from the title: Manas), as most specialize only in the Manas epic. Many consider their job a religious calling and have elaborate tales of how they were “touched by Manas” and became able to recite the poetic tale for hour upon hour while keeping their audience enthralled. However, again, while the scope of the manashi profession is impressive, it is not so unusual in the context of world culture and history. Homer was said to recite tales for days at a time. In Western Europe, as late as the 16th century, towns sponsored week-long dramatic marathons to present the major stories of the Bible, mostly for the benefit of those who could not otherwise read it. This function of remembering and reciting was vital to most cultures before the event of widespread literacy.

The presentational style of the manaschi is partially conventionalized, a trait more common in Asian theater than Western. Many sources describe the bards as speaking in a strongly rhythmic tone for the dialogue portions and a rapid, declamatory tone for the narrative. However, the manaschi are also expected to improvise if they are to be remembered as “masters” of their art. They embellish the story with extra description and explanation, and even answer questions from the audience without breaking their poetic structure.

In this way, the poem has remained an integral, flexible part of Kyrgyz culture. When the Kyrgyz adopted Islam in the 12th century, Manas became infused with its ideals, although he did not lose his pagan strength. His name is said to be built from the M in Mohamed, the N from Nabi (prophets), and the S is the crooked tail of a lion, the animal spirit of Manas. This might seem odd at first, but it is highly reflective of Kyrgyzstan’s unique version of Islam. Much like when Russia adopted Christianity, the new faith was grafted over the old, creating a sort of “double faith” (in Russian, this has a specific name, as it is fairly common in Eurasia: двоеверие – dvoeverie).

Bards use the poem to comment on modern politics; the fall of Soviet Union, an important event for the poem, has crept into the lines of some versions. During the Soviet Period, the poem and its performance were often censored as “bourgeois nationalist.” Officially, it was presented only in short fragments and with commentary comparing the forty tribes to the peoples of the USSR and how they should be unified. However, the full poem survived in private homes, with individuals continuing to learn and recite hundreds of thousands of lines of poetry by ear. Most people today say that they know of Manas through the stories their grandparents or parents taught them.

Manas remains potent and pertinent in Kyrgyzstan for many reasons. Kyrgyz families still trace their roots back to one of the forty tribes that Manas united. The official flag of the republic bears a sun with forty rays, representing those tribes, emanating from a tunduk, a symbol referencing the traditional yurt of Kyrgyzstan. The Tulip Revolution was fought in part because it was perceived that the president was too deeply entrenching his own tribe into politics and the economy at the expense of other tribes.

The Uyghers, incidentally, also still exist as a people. They are based mostly just across the Kyrgyz border in Western China, but also constitute 1.1% of the population of Kyrgyzstan. Relations with these minorities seem to be placid, however, and Uygher food is fairly widely available and well-liked in Kyrgyzstan.

Interview with a Manaschi, Nazarkyl Seydrakmanov

Interview taken by Eirene Busa in 2013. It has been excerpted and included in this resource.

As part of their study abroad program in Kyrgyzstan, SRAS studeants met with one of Kyrgyzstan’s most famous manaschis, Nazarkyl Seydrakmanov. During this meeting, Nazarkyl discussed his personal life story, the artistry of his craft, and gave an impromptu performance. He was above all else charming and captivating.

Wearing a soft kalpak, or traditional Kyrgyz felt hat, while leaning back into his chair with an unassuming demeanor and gentle smile, Nazarkyl entertained SRAS students for well over an hour at the London School. He patiently answered our questions in Kyrgyz and maintained friendly eye contact while his answers were translated into English. Now, to be sure, anyone who would so generously give up his time in the middle of the day, in the middle of the week, to talk to American students about a Kyrgyz tradition, would have been a rock star in my book. The fact that Nazarkyl has the title of Best Modern Manaschi in Kyrgyzstan Since Manaschi Legend Sayakbai Karalaeev made Nazarkyl my hero.

Nazarkyl’s story is the stuff of manaschi legend. He was born in 1951 in Talas, a small city in western Kyrgyzstan where Manas is supposedly buried. When he was eight years old, he had a dream about Manas, which, for many manaschis, is the equivalent of getting “the call.” But he did not think too much of his dream at the time. It was not until a few years later when he was asked to read to the old men in his village newly published versions of the Manas epic poem that he returned to the stories of Manas and discovered he was an exceptional storyteller. He began to memorize the Manas texts. While in the Soviet Army, he told the Manas stories to his comrades. After serving, he returned to his village in Talas and gained the reputation as one of the finest Manas storytellers around. In 1976, at the encouragement of his village, he participated in the “Competition of Manaschis and Akyns” in Bishkek and won first prize.

Nazarkyl has enjoyed a successful career. For 27 years, he served as a soloist-manaschi at the Kyrgyz State Philharmonia of Toktogul Satylganov, the prime venue for performance artists in Bishkek. He traveled to places like Germany, France, Iran, and Switzerland as the representative of the Kyrygz manaschi tradition. In 1995, he was the guest manaschi at Kyrgyzstan’s 1,000-Year Anniversary of the Manas Epic Poem in Talas, his hometown. To date that celebration is still Kyrgyzstan’s largest post-independence celebration. Nazarkyl has also performed on the TV program Babalardan kalgan soz (“The Heritage of Ancestors”) for three years. Now, at 61 years old, he teaches future manaschis in Bishkek at the Kyrgyz National Conservatory. In 2012, Nazarkul took part in a 41-day festival of manaschis, poets, writers and akyns (Kyrgyz bards) in Sonkol. He shows no signs of slowing down.

The most impressive thing about Nazarkyl is that despite his world-renowned career, he does not have a flashy personality. He is low-key and calm with an assuring smile that makes others around him feel immediately at ease. As SRAS students did their lightning round of questions during the Q&A session, he leaned back into his chair with almost a look of amusement. Here are some of his answers. They have been paraphrased from the rougher sequential translation.

What makes a manaschi a real manaschi?

A real manaschi has to believe that Manas is real. A real manaschi has to have a pure heart and pure soul. And like any artist or performer, a real manaschi has to work, work, work.

When did you know you “made it” as a real manaschi?

Winning first prize in a 1980s manaschi competition in Bishkek that looked for Kyrgyzstan’s greatest modern manaschi since Sayakbai Karalaeev. The competition, which was was organized by the Academy of Science’s Department of Research of Manas, was called “Who after Sayakbai Karalaeev can recite the three volumes of Manas.” (“Кто после Саякбая Каралаева сможет рассказать 3 тома эпоса Манас”).

Who are your favorite manaschis of all time?

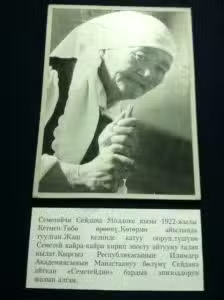

Sayakbai Karaleev (1894-1971) and Seidene Moldokeeva (1920-2006). They had two very different styles. Sayakbai, who was also known as the “Homer of the 20th Century,” was emotional, tender, and loud. Seidene, who was one of the few female manaschis, was softer. When you listened to her, you felt like you were sitting on a river bank.

Are there any performance rituals of the manaschis?

Before performing, manaschis can pray to the soul of Manas for protection. Or they can ask the ancestors for help. Sometimes manaschis offer good wishes to the audience. Often they will say, “I wish happiness and prosperity to my country.”

Do you have a favorite Manas episode?

No. The beauty of every episode depends on the manaschi himself.

Have you ever forgotten the lines?

It happens. But when it does, you just look around you, laugh with the audience, and then wait for inspiration to return. Losing contact with the spiritual world is like losing cell phone service. You just have to wait for it to come back. It always does.

In manaschi competitions, what criteria do the judges use?

Manaschis are judged according to voice, performance style, artistry, memorization, tempo, professionalism, and the quality of their answers in response to judges’ questions about Manas.

What can manaschis do to not lose their voice?

Manaschis control the musical contours and rhythms of their performances. Manaschis therefore should take care to not sing too fast or too loud. Manaschis should also pray to the spirit of Manas to protect them.

Has your style changed over time?

Of course styles change and develop, not only with time, but with the audience. Everything has to be matched.

After these questions, Nazarkyl gave a short performance from the second volume of the Manas epic, Semetei. (Semetei was Manas’ son.) He told a tale of how Semetei’s wife, Aichurok, turned herself into a swan and then stole her husband’s falcon. What was really fascinating for us, however, was watching him enter the “zone.” It was like watching the face of a runner about to embark on a marathon, or a politician about to make a speech. He wiggled around a bit in his chair first. He laughed nervously. He drank a cup of water. He looked out the window. Then he sat in silence for what seemed like a few minutes. As he did this, I thought about how nice it was that even a world-famous storyteller still had some performance anxiety.

But then inspiration struck — manaschis always have to wait for inspiration to strike — and, boom, he dove right in. The energy of the room changed immediately. He gave a rhythmic, pulsating performance, emphasizing every fourth beat with his right fist. First he started softly with a regular tempo. Then he got louder, faster, and the beats became more irregular. Sometimes he stretched the tempo, but then he would pull it back in for a regular beat. Then he stretched it again, only to pull it back in. It was as if he was making musical lagman noodles, stretching those rhythms and then slapping them back on the table with a steady beat.

At the end of the performance, the room burst into enthusiastic applause. Nazarkyl grinned. Then he concluded that an entire life would not be enough time to know or open all the secrets of the Manas epic. Even the ancient manaschis who told the Manas stories for three-month marathons could not cover everything. Indeed, the work of a manaschi is but a “little sand in a large desert.”

But Nazarkyl did not show a hint of despair. And for the first time I understood the deep spirituality of the manaschis. Manaschis don’t just memorize texts for the sake of art, but for a higher purpose — for the love of Manas, the love of our protective ancestors, the love of a history that defines and unites a people. It is all for love. And if you look into Nazarkyl’s face when he performs, that is exactly what you will see.

Manas Ordo: A Tribute to the Hero and His Legacy

Kyrgyzstan’s main Manas pilgrimage site is Manas Ordo, about five hours west of Bishkek in Talas Valley. SRAS students in the past have visited this site as part of the Russian as a Second Language and Central Asian Studies programs. For those planning to go on their own, doing it as a weekend trip is probably best, as a marshrutka from Bishkek’s Western Bus Station will take 5-6 hours to reach the Talas. Air service is also available between Bishkek and Talas.

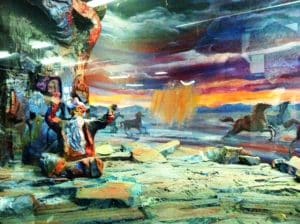

Manas Ordo is a partly open-air museum complex dedicated to Manas’ legacy, including his (supposed) tomb, a watchtower, cemetery, hippodrome, rose garden surrounded by statues of Manas’ 40 soldiers, a museum, and spruce trees donated by current and past Kyrgyz presidents, as well as visiting foreign delegations. Spruce trees are ubiquitous in the Tian Shan Mountains.

The complex was built in 1995, when Kyrgyzstan celebrated the 1,000-year anniversary of the Manas epic poem. To date, this celebration was Kyrgyzstan’s largest national celebration since independence. The Kyrgyz government pumped what is, for a small, poor, agricultural country, a fairly amazing eight million USD into the event. It was meant to showcase Kyrgyzstan as a newly independent state reviving its native culture. A major dramatization of the myth, involving hundreds of actors and technicians, was enacted. UNESCO also helped fund the event, recognizing the poem as a world heritage treasure.

Today, the biggest draw of the complex is Manas’ tomb, or gumbez, as it is known in Kyrgyz. Built in 1334, the tomb is a simple architectural brick beauty. Supposedly, the builders were instructed to inscribe words on the tomb saying that it was a mausoleum for a young girl to deter potential looters. Surrounding the tomb are gardens and benches, where visitors pray, reflect, read from their Quran, or just enjoy a time of quiet and tranquility. Indeed, the peaceful locale is so optimal that some locals pay a visit to the tomb at least once a week. While it is not a specifically Islamic site, it is certainly considered a spiritual one. And after seeing many Muslims hold up their hands in prayer, close their eyes, and then rub their face with a look of content and deep satisfaction, it is easy to understand why.

Manas Ordo is also popular for its mountain watchtower, Karool choku, which takes about 15 minutes to climb. At the top is a bright blue flag (with an image of Manas on top of a horse), and benches for more prayer, reflection, and enjoyment of Talas Valley’s stunning natural landscape. From its vantage, you can also see the rest of the complex, as well as roving sheep and goats on the mountains, an eerie amount of squawking ravens (why there are so many ravens there, no one could explain to me), and strolling wedding parties that come for wedding photos. Indeed, Manas Ordo is a popular photo destination, and in the summer and fall there are as many as three or four wedding parties at any given time.

Finally, Manas Ordo is popular for its comprehensive history museum. There, the story of Manas is brought to life through colorful dioramas, clothing items, horse accessories, and knowledgeable guides who can speak English and translate the Kyrgyz and Russian exhibitions. The most interesting exhibits for me were the ones about the manaschi, those who can recite the Manas epic from memory while adding their own improvisational style and musical rhythm. As I saw the black-and-white photographs and wax sculptures of famous manaschi devoting their lives to reciting the story of this mythological character, I appreciated Manas even more. He was more than a man, but a cultural muse who is still inspiring real people generations later to create unique artistic traditions and rituals. He also inspired people to act almost religiously. People would not only engage in the act of “praying” to him for help, assistance, and protection, but would also imitate styles of prayer. For instance, when I heard that the most famous manaschi, Sayakbai Karalayev, recited the Manas epic for 24 hours without stopping, I thought of Sufi whirling dervishes, who would whirl and whirl and whirl in trance-like meditation. How beautiful it must have been to witness these manaschi whirl the words of the Kyrgyz language with such grace and ferocity.

So, for me, the Manas legend and legacy is fascinating and dynamic. I’ll be curious to see how the Manas “brand” — or as some would call it, Manas “mania” — develops as the Kyrgyz government continues to develop its post-Soviet, post-Russian cultural identity. Or maybe the Manas “mania” will soon saturate. Whatever happens, I encourage you to join in the current fervor by driving out to Talas Valley and paying a visit to Manas Ordo. Being amidst the snow-covered Ala-Too mountains, reflective pilgrims, curious tourists, and the architectural beauty of Manas-inspired monuments, you will feel all the richer, both intellectually and spiritually.

Conclusion

The Epic of Manas is more than just a literary work—it is the foundation of Kyrgyz national identity, a living tradition that continues to shape and reflect the culture and identity of the Kyrgyz people. Whether through the monumental presence of Manas in Kyrgyzstan’s urban landscapes, the oral recitations of dedicated manaschi, or the ways in which his legend has adapted to historical and political changes, Manas remains central to Kyrgyz life.

At its core, the Manas tradition bridges the past with the present, demonstrating how oral epics and mythology serve not only as entertainment but as dynamic expressions of cultural identity. The dedication of manaschi like Nazarkyl Seydrakmanov ensures that the epic remains an evolving, living narrative rather than a relic of the past. Through their performances, they pass down history, values, and a shared sense of belonging, making Manas as relevant today as it was centuries ago. Manas endures as the ultimate symbol of Kyrgyzstan, a figure whose legacy continues to inspire and shape the nation’s future.

You’ll Also Love

Lagman: The Noodles of the Silk Road

Lagman is a dish that is very common in Central Asia, China, and many Middle Eastern countries. It can also be found in Russia and the Caucasus and is a popular dish among the Crimean Tatars. The basic recipe, which combines noodles with meat, has hundreds of variations. In Uzbekistan, the dish tends be a […]

Banyas in Bishkek – Cultural Experience

Banya (a washing house) has remained a part of the Russian culture since ancient times, carrying all sorts of traditionally obtained meanings including religious, symbolic and medicinal. The banya was officially endorsed by the Soviets as a health facility and its use spread throughout Eurasia. It remains popular for health and recreation throughout the post-Soviet […]

Kyrgyz Horse Games – a Day Trip from Bishkek

This year elections for the Issyk-Kul region were coming. This does not affect life much as a temporary student in Kyrgyzstan except that it means that the Бир Бол political party set up the Horse Games with free entrance for anyone! This was only a half hour walk outside of Cholpon-Ata. The games started about […]

Fortune Telling in Bishkek

Recently, a colleague and I went to a yasnovidyashi, a Kyrgyz fortuneteller (the name actually translates to “Clear Seer”), for the first time. Why? We’ve never done it before, we were looking for a new experience, and we were curious to know more about these infamous women of Bishkek with the “dangerous” reputation of hypnotizing […]

Samsa Traditions in Bishkek

I have always admired the “one cook, one dish” tradition. To paraphrase food critic Anthony Bourdain, this is the tradition where one lone artisan, or family of artisans, makes the same wonderful dish year after year, generation after generation, and by doing so, forms a close identification with the dish that ensures it is always […]