Easter breads such as kulich, paska, choreg, and nazuki are delicious Easter traditions. Easter is by far the most important religious holiday for those practicing Eastern Christianity. In addition to church services and egg dying, the holiday is also marked across the cultures by ritual bread baking.

Despite the wide geographic area covered by Eastern Christianity and the diversity in history and cultures to be found there, most recipes for Easter breads are remarkably similar brioche recipies, differing mostly in presentation and added flavorings.

The sweetness and richness of the breads are meant to symbolize the joy of the resurrection. However, most of these foods also pre-date Christianity and also pay homage to the older pagan traditions that Easter subsumed in these cultures. Thus, they also mark the rebirth of nature during spring and express hope for fertility and bounty in the coming agricultural season.

The Many Names of Easter Bread

All of the breads named below can be found online referred to as “Easter breads” in English, usually with a preceding adjective indicating the country of origin. The names used in the original languages, however, vary widely and come from many different sources.

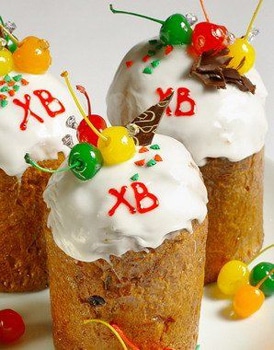

The kulich (кулич) is a major symbol of Easter in Russia and parts of Belarus, Ukraine, and Georgia. Its name is most often cited as originating from the Greek word “kollix,” which simply means “a loaf of bread.” However, the proto-Slavic “kolach” (kolačь), which refers to something round, is also very close phonetically to the Russian word and is still used in many Slavic languages to refer to round pastries and breads. The top of each kulich in Russian is called a “корона” (crown). It is usually topped with a powdered-sugar frosting which is often allowed to drizzle down the sides of the cake. The spikes created are meant to be vaguely reminiscent of Christ’s crown of thorns.

Armenia’s choreg (չորեկ) had its name derived from either Greek or Turkic, from a word that refers specifically to “round bread.” Choreg dough is baked as a wound snail-shell shape, a braided circle, or, most often, a braided oblong shape. This dish was once called bastir (պսադիր), a now-archaic Armenian name that referred specifically to Christ’s crown of thorns. It’s unclear when the linguistic shift occurred.

In the Balkans, Bulgaria’s kozunak (козунак) is related to the Bulgarian word for hair (коса), and refers to its trademark braided formation. The breads found in Serbia (pogača) and Croatia (pinca) have their names derived from the Latin “focaccia” and “pinsa,” respectively. Both sources refer to bread. Interestingly, Croatia also has pogača, but there the term refers to a puff pastry.

Paska is the term used in both Georgian (პასკა) and Ukrainian (паска) for their Easter bread. Paska is derived from “pesach,” the Hebrew word for the Passover, which is celebrated around the same time as Easter. The Russian word for Easter, “Paskha” (Пасха) comes from the same source. Meanwhile, Ukraine uses the term “Великдень” (The Great Day) to refer to Easter, similar to the Polish “Wielkanoc” (The Great Night). Interestingly, Russia also has an Easter-related food called “paskha” (пасха), although this is a sweetened mixture of quark, butter, dried fruit, nuts, and sometimes spices that is eaten on Easter, often as a spread for kulich.

Georgia also has an older and more native (although now rarer) Easter bread called “nazuki” (ნაზუკი), whose name, descended from Persian, translates roughly as “delicate.”

The Many Tastes and Presentations of Easter Bread

Despite the wide variety of names applied, nearly all of these recipes can be understood as variations of brioche. All are heavy on eggs and dairy fats. They are yeasted and allowed to rise at least twice to make the bread lighter and fluffier. They are produced in stylized forms, are lightly sweet, and often contain nuts, candied or dried fruit, zest, and/or various spices.

Interestingly, more distinct differences can often occur between families of one culture than occur between different cultures. Not only can the flavorings differ from family to family, but wide differences can be found in the ratios of flour to milk, butter, yeast, eggs, etc.

Yet there are also certain identifying factors, such as a specific presentation or certain flavorings, that mark a recipe as belonging to a specific type of Easter bread.

The kulich, for instance, is baked as a distinctive upright cylinder typically formed by baking the bread in aluminum cans or special store-bought paper forms. Nuts, raisins, vanilla, and/or a mix of chopped, candied fruits providing an array of colors are typical additions to the dough. The kulich is topped with royal icing and sometimes with nuts, dried fruits, or sprinkles for added color. Spices are almost never used, with turmeric perhaps the most common and added largely for color. The letters “ХВ” traditionally top the cake. They stand for “Христос воскрес,” or “Christ is risen,” the traditional greeting among Russians and Ukrainians at Easter. The response to this greeting is “Воистину воскрес” in Russian and “Воістину воскрес” in Ukrainian.

Paska, meanwhile, is sometimes identical to kulich in Ukraine. A second version, however, is typically wider than it is tall, although still thick and round. This version usually has no additions to the dough. The top of the bread is decorated with designs made from the bread itself, often a cross of braids, an “ХВ,” or other pattern. As it is rather plain, it is often served with condiments like butter and fruit preserves.

Paska and kulich are baked only for Easter. The breads below are baked for other special occasions as well or even throughout the year as regular dinner breads.

Pogacha is also typically baked without additions to the dough and baked year-round. However, for Easter it is usually baked in a braided or pull-apart formation with the individual pieces soaked in butter and the top brushed with egg before baking.

Kozunak is typically made from braided dough in an oblong, rectangular, or circular shape. The top of the loaf is brushed with egg, dusted with sugar, and often sprinkled with slivered almonds before baking. The dough is most commonly flavored with vanilla, lemon juice, and/or lemon zest. Raisins soaked in rum or brandy are also common additions. Sometimes a filling is placed between the braids that may contain nuts, chocolate, poppy seeds, dried fruit, Turkish delight, quark, cocoa, marmalade, and/or honey.

Choreg is highly distinctive by its use of spices. Mahleb (a spice made from ground cherry pits) is always added to the flour. Nigella seed (sometimes called black caraway or black cumin) either ground and added to the flour or sprinkled on top with sesame seeds before baking is also typical. Less common spices to add include mastika, fennel, anise, ginger, and/or others.

Nazuki varies greatly in shape and contents. At its simplest, it is just a sweet bread, baked as a round or oblong loaf. Sometimes it contains raisins and spices like cinnamon and cloves. Some recipes call for rather generous amounts of honey or a honey glaze. Others do not. It is traditionally baked in a tandir oven, which will give it a slightly smokey flavor, but it can be baked in a regular oven as well (but will not have that additional flavor).

All of the cultures these recipes come from have many other foods and, in a particular, other deserts (cakes, pastries, bars, etc.) that are associated with Easter.

The Symbolism of Easter Bread

For Eastern Christianity, Easter marks the end of the great Lenten fast. Thus, foods associated with Easter are typically given great importance as people return to their regular diets.

Easter breads are baked before Easter, often on the preceding Friday. They are then taken in a basket to church on Saturday with other foods meant to be consumed on Easter. Brightly colored hardboiled eggs are usually in the basket along with perhaps dairy fats, meats, and other items that had been forbidden to the faithful during Lent. The church holds a special service on the Saturday before Easter in which a priest blesses the basket of foods. Often, the breads, eggs, and dairy are eaten for breakfast on Easter – a good way to reintroduce fats to the digestive system before what is usually a heavy feast for Easter dinner.

That Saturday is one of the busiest for most Orthodox churches in Eurasia. It is said that the shape of the cylindrical kulich represents the tomb of Christ, while the white color of the bread symbolizes his purity and resurrection. Some cultures believe lower, circular breakfast breads represent Golgatha, the hill on which Christ was crucified. Kozunak, choreg and other braided breads often have three strands, representing the Holy Trinity. Sometimes the woven braid is cited as a symbol of eternity or of cycles like those found in nature.

The act of breaking and sharing bread is also reminiscent of Christ and the disciples and an act of unity for the family. Many breads, like pogachi, are made specifically to be pulled apart and shared.

The Russian kulich is often served with a beeswax church candle burning in the middle. This is a reminder of the Holy Spirit, part of the Holy Trinity.

Although today heavily associated with Christianity, the tradition of ritual spring breads dates back to ancient, pre-Christian times. In Russian mythology, the goddess of spring and fertility, Lada, is said to have baked kulich as a symbol of the renewal of life. Similarly, in Ukrainian mythology, the goddess of fertility and harvest, Marzanna, is said to have baked kulich to celebrate the arrival of spring.

Georgian nazuki is descended from a Persian food once associated with Navruz, the ancient Zoroastrian holiday still celebrated in many places in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and elsewhere. In fact, Georgians often present their Easter breads with freshly sprouted wheat grass, a distinct tradition also descended from Navruz celebrations.

In some cultures, the breakfast breads once carried other meanings as well. For instance, Russian peasants in tsarist times often baked several kulich breads for Easter. At least one would be for the family to eat, but another would be given to the local priest as a tithing and others fed to farm animals to ensure their health and virility. Still another might be baked and left in honor of dead relatives in a traditional “красный угол,” or “red/beautiful corner,” where Russian houses traditionally kept icons. Some also believed that the kulich could prophesize the family’s fate for the coming year. If the kulich rose well and formed nicely, the family would do well. But if the dough did not rise, or if the kulich crust cracks, then the family could expect misfortune. Russian peasants typically baked simpler kulich breads than those eaten today, with local fruits and no frosting, marked only with a cross cut in the top.

Today, it is common to not bake your own Easter breads in many cultures. Instead, you can place an order at a local bakery or, perhaps more commonly, simply buy one from the stacks that appear at grocery stores or even roadside stands.

In any case, Easter breads are ancient traditions that still play a strong role in the cultures of Eastern Christianity today. This Easter, try to make one yourself!

Let’s Cook!

Kulich (Russian Tradition)

Ingredients

- Kulich paper forms or similar high ceramic baking molds.

- 100g – dried fruits (raisins or chopped, dried apricots are most traditional)

- 100ml – room tempature water

- 160ml – warm milk

- 25g – raw yeast (may substitute 10g of dry yeast, but raw yeast is preferable)

- 200g – sugar

- 5 egg yolks

- A pinch of salt

- Vanilla to taste

- 450g – Flour

- Butter (soft) – 100 g

Preparation (Dough)

- Put the dried fruits in room temperature water and set aside.

- Pour the warm milk into a bowl, add 50g of sugar and the yeast, whisk well and let stand for 15 minutes to let the yeast activate.

- In a bowl, combine egg yolks, vanilla, and salt with the rest of the sugar and the activated yeast mixture. Combine well.

- Gradually add 350 g of sifted flour. Knead the dough for about five minutes.

- Now add 100 g of soft butter and another 50 g of flour and knead the dough for about 10 minutes.

- Let rise for about 2 hours. It is recommended to set your oven to 90 degrees and let it rise in the oven.

- Drain the dried fruits in a colander, coat them in 50g of flour and knead them into the risen dough.

- Fill your molds about halfway with dough. Cover, and allow to rise for one hour (again, in an over at 90 degrees is preferable).

- Increase the oven temperature to 180 degrees and bake for another 25-30 minutes. You may need to adjust this based on your molds. Bigger molds will cook longer, smaller molds a shorter time. If you can push a bamboo skewer through the center of the bread and have it come out clean, the bread is done.

Preparation (Icing)

- Wait for the the bread to cool, then, lightly whisk one egg white until frothy (not stiff).

- Gradually add the sifted powdered sugar, a little at a time, whisking continuously until smooth.

- Add the lemon juice and whisk again until the icing is thick and glossy.

- Use immediately.

Paska (Ukrainian Tradition)

Ingredients

- Paska paper forms or similar high ceramic baking molds. Your will want something wide to leave room for the decorations.

- Bamboo skewers

- 0.5l warm milk;

- 30g fresh yeast (may substitute 10g dry yeast, but fresh is preferred)

- 150g sugar

- 5 egg yolks

- 200g butter

- 850g sifted flour

- A pinch of salt

- 30g vegetable oil

- 200g raisins.

Preparation

- Mix warm milk, 2 tbsp. sugar, and yeast. Whisk well. Add 1/2 cup of flour and whisk well. Cover and set aside in a warm place for 30 minutes.

- Combine soft butter, sugar, salt, and egg yolks and beat until smooth. Add the yeast mixture and gradually add the rest of the flour. Knead the dough just until it gets sticky and stretchy.

- At this point, put the mixture on an oiled surface and knead very well. This will require about 30 minutes by hand or 15 in a dough mixer. The dough will be elastic and not sticky at all.

- Cover and return the dough to its warm place for an hour and a half.

- Soak the raisins in boiling water for 15 minutes. Drain and dry them. Then coat with 2tbsp of flour.

- After the dough has risen, punch it down and separate a quarter. To other batch, add the raisins, knead well to incorporate. Return both batches of dough to their warm place to rise for another hour.

- Fill the molds with dough about 1/4 full. From the dough without raisins, make decorations. A braided cross is fairly easy and very traditional. Keep in mind that this dough will rise again, so do not make the decorations to big. Run a bamboo skewer upright through the center – this will help the dough rise evenly without disturbing the decorations.

- Once the dough has risen again by about 200%, coat the top with beaten egg yolk and bake in the oven at 160-170°C for about 40-50 minutes.

Choreg (Armenian Tradition)

Ingredients

- 250ml whole milk (warm, about 40–43°C)

- 25g fresh yeast

- 110g granulated sugar

- 2 large room tempature eggs

- 115g unsalted, softened butter

- 1tsp salt

- 1½ tsp ground mahlab

- 1tsp ground nigella seed

- Sesame seeds

- 550g all-purpose flour

- 1tbsp warm water

- 1 egg yolk

Preparation

- In a small bowl, crumble 25 g fresh yeast into the warm milk (250 ml) with 10g sugar. Whisk well and let sit for 10–15 minutes until frothy.

- In a large mixing bowl, beat 2 eggs and 100g sugar until well combined and slightly frothy. Stir in the softened butter (115 g), salt, mahlab, and nigella seed. Add the activated yeast mixture and stir, gradually adding in the flour.

- Once thick and sticky, turn onto a floured surface or knead for about 10 minutes. Place the dough in a lightly greased bowl. Cover and place in a warm place for 1.5 to 2 hours, or until doubled in size.

- Punch down the dough and divide into three equal parts. Roll these into long cylinders, braid them, and transfer to a parchment-lined baking sheet. Cover and let rise again for 45–60 minutes, until nearly doubled.

- Mix egg yolk and water until lightly frothy. Brush this over the top of the loaf. Sprinkle with sesame seeds.

- Bake for 25–30 minutes in a preheated 350°F oven.

Nazuki (Georgian Tradition)

Ingredients

- 1kg flour

- 350ml warm milk

- 300g sugar

- 200g sour cream

- 4 eggs

- 20g dry yeast

- 75g oil

- 1/4 tsp ground cloves (optional)

- 1/2 tsp ground cinnamon (optional)

- Vanilla to taste (optional)

Preparation

- Mix the yeast with 100ml warm milk, 1tbls of sugar, and let sit for 15 minutes or until frothy.

- Whisk two eggs, the rest of the milk and sugar, the sour cream, oil, and any flavorings you are using together with the activated yeast mixture.

- Gradually add the flour. Once all flour is added, knead for 10 minutes until smooth, soft, and just slightly tacky.

- Cover in an oiled bowl and let rise for 1.5 to 2 hours, until doubled in size.

- Punch down the dough and divide into equal portions, forming them into circles or kidney shapes. Transfer them to a parchment-lined baking sheet, cover, and let rest for 45 minutes.

- Beat the remaining two eggs and brush across the tops.

- In a preheated, 350F oven, bake for 25-30 minutes.

You’ll Also Love

SRAS has developed the test below to help you gauge your Russian language skills! Anyone interested in gaining more knowledge should check out the the resources under “language” on our main menu including especially our Resources for Students of Russian and the Russian Talking Phrasebook. You can also sign up to study Russian online or […] The following TORFL reading comprehension practice test has been developed by SRAS based on the official TORFL test to help you gauge your knowledge of the Russian language! Anyone interested in gaining more knowledge should check out the the resources under “language” on our main menu including especially our Resources for Students of Russian and […] The following TORFL grammar and vocabulary practice test has been developed by SRAS based on the official TORFL test to help you gauge your knowledge of the Russian language! Anyone interested in gaining more knowledge should check out the the resources under “language” on our main menu including especially our Resources for Students of Russian […] The below test has been developed by SRAS to help you gauge your knowledge of the Russian language! Anyone interested in gaining more knowledge should check out the the resources under “language” on our main menu including especially our Resources for Students of Russian and the Russian Talking Phrasebook. You can also sign up to […] Olga here turns her attention to the modern Russian circus, describing what it is like to attend a contemporary performance, from the atmosphere inside the circus building to the acts that still draw enthusiastic audiences today. Written in simplified, modern Russian, her account offers a firsthand glimpse into how a traditional cultural institution continues to […]

Advanced Russian Language Test

Free Online TORFL Practice Test: Reading Comprehension

Free Online TORFL Practice Test: Grammar and Vocabulary

Basic Russian Language Test

The Circus in Russia: Olga’s Blog