History of Central Asian Weaving

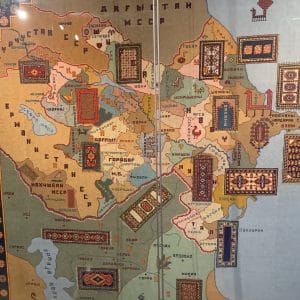

Central Asia has one of the world’s oldest traditions of carpet weaving. The oldest known carpet, dating back 2,000 years, was found in the Pazyryk Valley—located in present-day southern-central Russia near the Kazakh and Mongolian borders. At the time, the valley was inhabited by the Scythians, nomadic tribes who roamed Central Asia before the Mongol conquest. Some scholars believe the carpet may have been made by Armenians or Persians, whose sedentary lifestyles better supported the complex infrastructure required for rug weaving. Regardless of its origin, the carpet’s presence in the Pazyryk Valley reflects both the use of woven rugs by nomadic peoples and the sophistication of regional trade networks even in ancient times.

Farther south, interactions between nomadic and sedentary groups continued to shape the craft and economy of rug weaving. Among the Kyrgyz and Kungrat tribes of Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, respectively, carpets, both woven and felt, were fully integrated into daily life. Rugs served both practical and decorative purposes in yurts: insulating floors, serving as folded furniture, or hanging to divide the large yurt space into rooms. Rugs also enhanced the yurt’s appearance, providing warmth and beauty in what could be a harsh climate. A bride’s dowry traditionally included rugs she had created. Their craftsmanship reflected her skill and readiness for married life.

In major cities like Samarkand, rug weaving developed into a thriving industry, especially under the generous patronage of Amir Timur. Spanish ambassador Ruy González de Clavijo, writing of his visit to the Timurid court in 1404, described silk rugs embroidered with gold thread.

In the 19th century, as Russian imperial forces expanded into Central Asia, carpet weaving became part of the empire’s efforts to study and classify the region’s diverse peoples. Russian scholars published academic works that asserted intellectual authority over local knowledge, displacing traders and artisans in shaping the narrative. These publications and exhibitions brought Central Asian carpets to a broader audience in Russia and abroad.

Under the Soviet Union, rug weaving was repurposed to fit socialist ideals. Factories replaced homes as the main sites of production, and portrait carpets (kovry-portrety) featuring Lenin and Stalin became popular as cults of personality arose. As art historian Vera-Simone Schulz notes, these rugs were celebrated as a way for Turkmen and other groups located on the edges of the country to participate in Soviet visual culture. Traditional weaving continued, but the process was industrialized and collectivized.

Today, both local and international organizations are working to revive traditional rug weaving as a cultural and artistic heritage practice.

Technical Details and Design

Rugs in Central Asia generally fall into two categories: flat weave and pile. Flat weaves are made with long, continuous strands that create a tight, smooth surface, while pile rugs have cut fibers that give them a fur-like texture. Flat weaves are quicker and cheaper to produce and are typically used as floor coverings, while pile rugs, with their softer and more luxurious feel, are often used as wall décor.

Rug making begins with forming the base—the structural foundation made from cotton, camel wool, or goat wool, all valued for their strength and low elasticity. The weave, worked through this base, is made from sheep wool, which is softer, more flexible, and better at absorbing dyes, making it ideal for crafting detailed patterns and comfortable textures.

The material is first cleaned, brushed, and spun into thread using vertical looms, which allow fibers to be stretched and twisted into even, durable strands. This process, typically done by hand and often by women, requires both strength and skill to ensure the thread is even and strong enough for weaving. The spun thread is then woven on horizontal looms, usually laid flat on the ground. The warp threads are stretched across the frame, while the weft is woven through them to create flat weaves or tied into knots to form pile.

Large carpets can be woven in sections and stitched together. Natural dyes made from roots, flowers, and fruit juices were once used—for instance, black was created by boiling iron or walnut peels with pomegranate rinds.

Often, women work in groups. A pair of National Geographic journalists traveling Turkmenistan in 1973 described the process: “A weaver…knots a strand of wool around a thread of warp, cutting the ends with the sickle-shaped knife. After each row she tamps the line with a heavy comb. Finally, using shears, she clips several inches of shaggy tuft to an even height. The weavers work with every ounce of their energy, burying their joys and sorrows alike in their carpets, forgetting even the baby in its hammock hung above the loom.”

Zoomorphic and phytomorphic designs are popular motifs that likely began as detailed depictions of real beings rooted in local shamanistic beliefs, but gradually simplified into geometric shapes. In Kyrgyzstan, in regions near the Ferghana Valley, common decorative motifs include the curl (kaykalak), hoof (tai tuyak), wolf’s eye (boru gozu), knife tip (bychak uchu), star (jyldyz), and dog’s paw (ala monchok). The octagonal “kalkaanushka” emblem, originating with the Oghuz tribes between the Caspian and Aral seas, appears across Turkic carpets—including Azerbaijani—highlighting migration and cultural exchange. Historically, carpet emblems served as tribal coats of arms, a significance that endures today: Turkmenistan’s flag features five emblems representing its main tribes—Salor, Yomut, Tekke, Chaudor, and Saryk. This tradition is so central to national identity that Turkmen Carpet Day is celebrated annually on the last Sunday of May.

Carpets are a means of learning about Central Asia’s history, culture, and economy. It is an integral part of Kyrgyz identity, Uzbek identity, and many others. A trip to the region would be incomplete without a tour of a crafts museum or applied arts workshop such as these in Bishkek!

You’ll Also Love

Navruz, Nooruz, Nowruz: The Ancient Spring New Year of Central Asia

Navruz is a spring solstice celebration that marks the beginning of the New Year according to the traditional Persian calendar. It has been a beloved holiday for some 3,000 years, surviving cultural change caused by centuries of tumultuous history. It was once celebrated on the vernal equinox but is now celebrated on the set date […]

Chak-chak: A Glorious and Celebratory Fried Honey Cake

Chak-chak (Чак-чак) (chak-chak) is a dessert food made from deep-fried dough drenched in a hot honey syrup and formed into a certain shape, most commonly a mound or pyramid. It is popular all over the former Soviet Union. In Russia, chak-chak is especially associated with the Tatar and Bashkortostan republics, where it is considered a […]

Victory Day in Russia and Other Countries: Vocabulary and History

Victory Day is a holiday of significance in many Eurasian cultures, but particularly stands out in Russia. People pay homage to veterans and remember the sacrifices that were made for the sake of victory in WWII. While Victory Day is deeply ingrained in Russia’s national identity, its observance across Eurasia reveals nuanced changes or adaptations […]

Plov: A Central Asian Rice Staple

Plov (Плов) is a hearty dish made from deep fried meat and vegetables, over which rice is cooked. Plov is considered a national dish in many countries of Central Asia and the Near and Middle East ‒ Iran, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Afghanistan. It is generally popular over most of the area that the Soviet Union […]

Halva, Halwa, Helva: A Hundred Sweets from Dozens of Cultures

Halva, the rich dessert well-loved across many cultures, is so densely filling it almost manages to feel like a meal – and not an entirely unhealthy one at that. There are more than one hundred varieties of halva, an ancient dish whose base can be flour, ground seeds or nuts, or fruit, depending on where […]