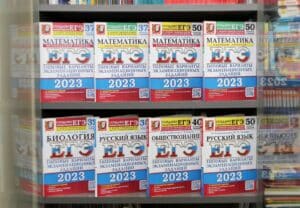

The exit exams that Russian students take to exit high school are known as the Unified State Exam (USE), also known as the “EGE” (ЕГЭ – Единый государственный экзамен) in Russian. The USE to replace the previous system of entrance exams for higher education institutions and was intended to work like the SATs in the US.

Olga Dmitraschenko took these exams in Moscow in 2006, after completing her high school experience via home schooling. She wrote of her exam experience in the text that follows as part of a series of free Russian lessons sponsored by SRAS called Olga’s Blog, which documents – in simplified, modern Russian – her experience finishing high school, starting college, and living life in Moscow in 2006. The text, links, and format of this resource were last updated in 2023.

Briefly About The Unified State Exam

The USE is a standardized test that assesses students’ knowledge and skills in a range of subjects. Students are currently required to pass mathematics and Russian language. They can also choose from fifteen other subjects including foreign languages, physics, chemistry, biology, history, social studies, and literature. These are chosen, usually based on the student’s strengths (what they can score highest on) and what degree program they intend to apply to (what they need to show competence in). Students typically take the exams in their final year of high school, with the results being used to determine eligibility for admission to universities and other higher education institutions.

The exams, introduced in 2001, are administered centrally and are typically held over a period of several weeks in the spring. The format of the exams varies by subject, but typically includes multiple-choice questions, short-answer questions, and essays.

They are graded on a scale of 1 to 100, with passing scores varying for each subject. Grading is complex, with each question weighted separately and the end result calculated by a computer algorithm. The exams were developed and are administered by Russia’s Federal Institute of Pedagogical Measurements, which also develop and administer several other standardized tests.

The USE has been controversial in Russia. It is a high stakes exam that causes considerable anxiety with students and parents not only because of its singular importance to a student’s future, but also because of confusion about how it is graded. It has also not erased the culture of cheating that it was meant to. Indeed, it is considered standard for students to cheat and for proctors to turn a blind eye. Some critics have also pointed to the considerable costs associated with creating and administering the exams. Nevertheless, the USE remains a key component of the Russian education system and is an important part of the process for students to exit high school and pursue higher education.

Russia’s Unified State Exams: Simplified Russian Text from Olga’s Blog

This is Lesson 2 of Olga’s Blog, a series of free intermediate Russian lessons.

Note that:

- All of the bold words and phrases have annotation below.

- Red words and phrases indicate the subject of this blog entry’s grammar lesson.

- *Asterisks indicate slang.

Дорогие друзья! Снова привет!

Сегодня давайте поговорим про самое страшное и ужасающее – экзамены.

Экстернат дает опыт сдачи экзаменов – здесь очень часто бывают зачеты и устные ответы. И к началу вступительных испытаний старшеклассники не парятся* по этому поводу. Несколько раз в неделю в классах проводятся тесты и опросы, и если ты хорошо отвечаешь на уроках, зачет по предмету тебе ставят автоматом. Экстернат помогает снять перегрузки и сохранить здоровье – как физическое, так и психическое. За последние лет десять число учащихся в экстернатах увеличилось почти в двадцать раз. Думаю самая главная причина этого – возможность заниматься самостоятельно и самому планировать свое обучение.

Но в экстернате не легче учиться, чем в школе. Здесь приходиться тоже много работать, чтобы получать высокие оценки. Система оценивания в России отличается от систем во многих других странах. Расскажу об этом подробнее:

В России при окончании школы выдается аттестат – маленькая книжка с оценками по всем предметам. Оценки у нас отличаются от тех, которые ставят вам в Америке, например. У нас не буквы – A, В, С, D, F, а цифры – 5, 4, 3, 2:

5 – отлично

4 – хорошо

3 – удовлетворительно

2 – неудовлетворительно.

Иногда ставят оценку “единица,” но это в том случае, если учитель очень недоволен твоей работой. Это бывает редко, но бывает. Обычно после этого ученик пересдает работу, поэтому ничего страшного. Ведь любую оценку, при желании, можно исправить.

Вот еще что интересно – если ученик заканчивает школу со всеми оценками пятерками, ему выдают золотую медаль. А если с одной или двумя четверками, он получает серебряную медаль. Именно ее я и получила, потому что у меня была одна четверка по литературе. Как это случилось? Думаю, вам будет интересно подробно послушать про школьные экзамены. Если ученик хорошо занимается в течение года, и при окончании школы у него нет двоек, то он сдает пять экзаменов – два обязательных (сочинение, математика) и три устных экзамена по выбору (любые три предмета из школьной программы).

Я выбрала английский, русский язык и географию. С предметами по выбору было легко – на английском нужно было пересказать текст и рассказать тему, по географии рассказать про любую страну мира, по русскому устно сделать грамматическое задание к тексту. Основные же экзамены – письменные и долгие. Экзамен по математике состоял из 6 заданий, и длился четыре часа. Сочинение длилось шесть часов, потому, что считается самым сложным экзаменом. Но мне оно показалось не очень страшным, потому, что литература – мой любимый предмет. Только вот поставили за него четверку. Ведь письменные экзамены медалистов проверяли пять комиссий (двадцать учителей) в Департаменте образования города Москвы, и любая маленькая неточность считалась ошибкой. Но, во время обязательных экзаменов нас кормили едой из Макдоналдса, так что нам очень повезло.

Не обошлось, конечно, и без шпор.* Одни прятали их в ботинки, другие писали на руках, а самые сообразительные выходили в «туалет» и звонили своим репетиторам. В этот раз, никого не пропалили.*

И хватит кошмаров, в следующий раз будет кое-что повеселее… присоединяйтесь!

Vocabulary and Cultural Annotations

Париться: slang term meaning to worry or get upset (literally – to sweat or steam). Standard words to use in situation are волноваться or переживать.

Тесты и опросы: tests and oral examinations. Russian education often uses both written and oral testing; Опросы are always oral. Other words for “test” include экзамен (exam) and зачет (test, but usually a large or important one – like a final).

Ставят автоматом: “automatically placed.” In the Russian system, if the student has passed all examinations, the student need not take the final (зачет) to pass the course.

Лет десять: about ten years. In Russian, if the number is set before the word it describes, the figure is exact. If the number is set after, it is approximate.

Оценка: grade. The word is also used to mean “appraisal” (as in a house appraisal).

Система оценивания: grading system. Russia uses the same grading system once used across the USSR and in most Eastern Block countries. The world has a surprising array of grading systems – see Wikipedia for more information.

Аттестат: basically a diploma and a transcript placed in one bound document.

Оценка “одиночка:” A “one” (grade). A one is an unofficial grade which is no different, academically, from a two. Teachers use it to express extreme displeasure with a student or a student’s work. Imagine if teachers in the US could give an “F-” to particularly incorrigible students! A “2” is considered failing in the Russian system.

Пятерка: A five (referencing the grade or numeral). Other grades are read as follows: четверка; тройка; двойка; and одиночка. Forms of these words are also often used by teachers amongst themselves to refer to students. For an example, an “A” student would be known as a “пятерочник” (male) or a “пятерочница” (female). A poor student is a “двоечник” or a “двоечница.”

Серебряную медаль: silver medal. The medals, which are actually gold- or silver-plated, are produced by the federal government of the Russian Federation and distributed locally at the schools.

Школьные экзамены: essentially, these are “exit exams.” Upon completion of their secondary education, Russian students must pass a set of government exams in order to graduate. The exams may not be taken if the student has any failing marks (“2″s or “1”s) on his/her record. The grades received on these exams are included on the student’s аттестат.

Сочинение: writing/composition. Note that this is now part of the wider Russian Language exam that is now required. Things have changed a bit since 2006.

Шпора: slang term meaning “crib sheet,” a sheet of paper (or other material or object) with test answers written down in advance. Literally, a шпора is a spur, the device worn on the heels of boots to make horses run faster. It sounds like another word in Russian, also slang but more widely used and accepted, “шпаргалка,” which also means “crib.”

Репетиторам: coach, trainer, or private tutor. Private tutors are often hired in preparation for exams. It is common primarily because teachers’ salaries are so low they will readily take on the extra work at low rates so as to make ends meet.

Пропалить, запалить: slang terms meaning “to catch someone (in the act of doing something wrong).” As in “Его родители пропалили, что он курит.” Interestingly, “палить” is literally “to burn” or to “to shoot (a gun).”

Присоединяйтесь!: join us! Literally, this translates to “unite with us!” This type of phrasing was greatly popularized under the soviets by the constant repetitions of the last lines of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto, which read in Russian as: “Пролетарии всех стран соединяйтесь!” (Workers of the world, unite!) It remains popular as a jovial or sometimes humorous manner of speech.

Grammar Focus: Present Active Participles

This is the second part of this grammar focus. This installment covers cases without referents. The first installment was a general introduction.

“Ужасающее” is a example of a present active participle.

Ужасать (to horrify) – ужасают (they horrify) – ужасающий (horrifying)

However, notice that in this case the participle is used slightly differently. In the first example: Экстернат – это образовательная программа на платной основе, позволяющая школьнику пройти курс обучения за короткий срок, the participle позволяющая has a clear referent: программа. However, in today’s example: (Сегодня давайте поговорим про самое страшное и ужасающее –экзамены), the participle ужасающее has no specific referent. This type of usage is perfectly acceptable in Russian. Today’s phrase may be translated as “Today, let’s talk about the scariest and most horrifying (thing) – examinations.”

If an adjective (including a present active participle used as an adjective) is used without a referent in Russian, it refers generally to anything that adjective can describe. So, in this case, ужасающее is used to refer to all that which is horrifying. Adjectives used in this manner are most often used in the neuter form if they refer to something inanimate or abstract.

Examples from Literature and the Press

Самое страшное – это чувство бессилия. Н. Меликова

Самое интересное еще впереди. Common saying.

“Самое лучшее” – “The Best” (common album title – see this one by A. Герман)

Adjectives can also be used to refer to groups of people or things. In this case, they appear in plural form.

Желтое, козлиное лицо лежащего на полу существа изменилось, огромные черные глаза ужасающе запали. Г. Лавкрафт (in translation)

В итоге наш товарищ выступил в самом конце, в зале оставались, напомню, самые стойкие и непоколебимые. Б. Игнатов

Люди нюхают – / запахло жареным! / Нагнали каких-то. / Блестящие! / В касках! В. Маяковский

More Free Russian Lessons From Olga’s Blog

The Language and History of Caviar: Olga’s Blog

Olga below describes the place of caviar in Russian food culture. In simplified Russian, she describes where the delicacy is harvested from, the major types of caviar, and how the types differ in cost and quality. We also provide an English primer below discussing more of the history of caviar, how it is eaten and […]

Mushrooms in Cultures and Cuisines: Olga’s Blog

Olga below continues her discussion of the deeply held place that mushrooms have in Russian culture. In part one of this discussion, she focused on how and where and find the mushrooms. In part two, below, she discusses how the mushrooms are preserved, prepared, and consumed. A staple of the regional diet for centuries, mushrooms […]

Mushroom Season Has Begun! Olga’s Blog

Olga below discusses the deeply held national tradition of mushroom gathering. An important part of Russian food tradition for many centuries, Russian children are taught in school from an early age to tell the difference between various types of native mushrooms. Many, like Olga, will go with relatives and friends to the woods to put […]

Study Abroad in America for Russians: Olga’s Blog

As part of her major program in international relations at Moscow State University, Olga applied to study abroad in the United States in 2007. As was not uncommon for students applying for study abroad in either direction, Olga hit several bureaucratic snags. What is perhaps most remarkable about the below text, however, is the description […]

What is the First Day of University Like in Russia? Olga’s Blog

Below, Olga discusses what a first year freshman experiences on day one of their college education. The day offers no classes. It is instead filled with speeches, handshakes, and status symbols. All of this is highly indicative of the role of formality and ceremony in Russian education and Russian society. This resource is part of […]