(The Soup that Makes a Man as Strong as a Wall: from the Old Silesian saying “Ze żuru, chłop jak z muru” (Literally: from żur, a man is like he’s made from wall)

Żurek is a sour soup made from fermented rye flour with sausages, potatoes, eggs, and spices. It is popular across Poland in a variety of regional tweaks. Żurek is also eaten in Belarus (as Жур) and in slightly different forms in Slovakia (as kyslóvka) and the Czech Republic (as kyselo). In Poland, it is usually eaten in its full form (with sausage, etc) on Easter, although it is also eaten during Lent (by traditional families) without meat and usually only flavored with salt and garlic to symbolize fasting, sacrifice and self-denial. On special occasions it is served in a bread bowl. It is considered a strong part of Polish culture and has been eaten in Poland since at least the Middle Ages.

How Żurek Got Its Name

(Dlaczego “żurek” jest tak nazywany?)

Żur, as the soup is sometimes referred to (“Żurek” is just a Polish diminutive of Żur), is probably derived etymologically from the Old High German “sur” (modern German “sauer,” a cognate of modern English “sour”), according to Aleksander Brueckner’s etymological dictionary of the Polish language. Brueckner argues that the word “żur” was borrowed from the German and became widespread in the 15th Century in Western Slavic languages (Polish, Slovakian, Czech, and Sorbian) and then later gained currency in Russian from the Western Slavic languages. There is some debate about this, however, with some scholars arguing other origins.

Żur is also closely related to “barszcz biały” [bahrshch byawy] (white borscht). “Barszcz biały” uses wheat flour for its base instead of rye flour and doesn’t always contain sausage. This technical differentiation, however, is really just that. There is in fact more variety between regional takes on Żurek than there is between the archetypal żurek and the archetypal “barszcz biały.” In the northeast of Poland, for example, it is more common to use buckwheat (rather than the typical rye flour) in żurek as the base, whereas oat flour is more common in the south of the country.

Most Polish sources seem to agree that today the two names are more or less used interchangeably to refer to sour fermented soups with a flour base. Historically, however, the two soups were different. Apparently “barszcz biały” was once made from fermented leaves of hogweed, rather than wheat flour. Needless to say, that historical recipe long since gone out of vogue.

When and How Żurek is Eaten

(Kiedy Polacy jedzą żurek?)

In Poland today the soup has become a widespread staple of Polish cuisine and is usually offered on a daily basis at Polish workers’ cafeterias or milk bars (bar mleczny). Traditionally, however Żurek is eaten in its most extravagant form (with ample amounts of Polish sausage (kielbasa and potatoes) on holidays, especially Easter.

According to Maria Dembińska’s Food and Drink in Medieval Poland, many Polish peasants used to keep (until quite recently actually) a ceramic pot especially for making “zakwas” (the sour base) for żurek. The pot was not washed, which allowed the fermentation from the previous batch to act as starter for the next. “Zakwas” is derived from the Polish word for “to ferment” (and is related to the Russian word “закваска,” which also refers to something fermented and is commonly found when referring to the preparation of Russian dairy-based beverages).

As aforementioned, during Lent the soup would only be flavored with basic spices and thus the soup came to eventually occupy a cultural symbolic space in Polish literature as a metaphor for sacrifice and self-denial. Indeed, at the end of Lent, the “zakwas” pot would be symbolically “killed” by either smashing or burying it. Apparently, Polish archeologists have uncovered a number of such pots in medieval finds in Poland, providing material evidence for the longevity of this tradition.

Cooking Traditional Żurek

(Jak odpowiednio ugotować żurek?)

Preparing żurek in the traditional way takes literally days, so don’t expect to be able to make it for dinner without the help of modern “cheats.” The first step in cooking żurek is preparing the “zakwas” or sour base that gives żurek its signature tang. If this is your first batch of “zakwas” or if you’re using a clean jar, you’ll need a starter to help the fermentation process along. Typically the crust of a piece of rye bread is used (the yeast and bacteria in the bread will start the fermentation process). Although a number of different regional preferences for bases exist, the typical choice is rye flour. The rye flour is then mixed in a jar with water and the fermentation starter or with the residue of former zakwas batches and left to ferment in a warm place (around 70-80⁰F) for two to six days, depending on the level of sourness desired (the longer the zakwas ferments, the more sour it will be). If bread has been used as a starter, it should be removed from the surface of the water after a couple of days before mold starts to form on the bread. If you’re in a hurry, you can also use a prepackaged powder base (sold by Knorr in Poland, for example, as instant żurek or barszcz biały), instead of fermenting your own “zakwas.”

Let’s cook!

(Gotujmy!)

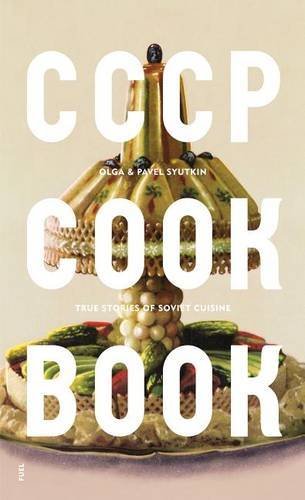

See below for a free recipe for żurek. See also the free videos online. If you are interested in cooking from Russia, Ukraine, Georgia, and other places in Eurasia, make sure to see our full, free Eurasian Cookbook online! You might also be interested in the following specialized cookbooks we’ve enjoyed:

|

|

|

|

| Żurek | Żurek |

| Składniki

Zakwas

Żur

Przygotowanie

|

Ingredients

Sour Base

Sour Soup

Preparation

|

Our Favorite Żurek Videos

This is a great video in Polish that shows the entire process of making homemade Silesian żurek ‒ from preparing the “zakwas,” to cooking the soup, to showing how to serve the final product in a bread bowl. Just a note, though: this version of żurek uses mashed potatoes instead of the standard pieces of boiled potato. The use of mashed potatoes and bacon is typical of Silesian żurek, common around the Wrocław area in South-Western Poland.

This Polish-language video demonstrates every step in making “zakwas.” It also includes a useful onscreen list of ingredients as a reminder and shows the removal of the solid matter (bread, garlic) from the “zakwas” after a few days of fermentation.

This video shows famous Polish chef Magdy Gessler making “barszcz biały,” a tasty analogue to żurek.

You Might Also Like

Polish holidays are heavily steeped in Catholic tradtion. They all have a distinctly Polish flair to them, however, in their foods, colors, and celebrations. Note that in Poland nearly everything closes for public holidays! Everyone will be celebrating! Find out more about Polish holidays, their history, cultural significance, and related days off below. Days Off […] What shapes Polish national identity? The answer is complex and personal, but one key element is the Polish national narrative. This includes the heroes and pivotal events taught in schools, the places central to the nation’s collective memory, and the language and beliefs that frame its worldview. A national narrative goes beyond history: it is […] Catholic Mass in Poland is not only a religious ritual but also a reflection of the nation’s history, culture, and identity, shaped by centuries in which Catholicism anchored Polish society through partitions, war, and communism. Today, around one-third of Poles attend Mass weekly and 71% identify as Catholic, making Poland one of Europe’s most religious […] The Talking Phrasebook Series presents useful phrases and words in side-by-side translation and with audio files specifically geared to help students work on listening skills and pronunciation. Each entry below, divided by category, features an English word or phrase in the left column and its Polish translation in the right. In the center column for […] Polish food is hearty, flavorful, and deeply rooted in tradition. It is also experiencing a revival, re-inventing itself in major Polish cities as the country celebrates its heritage and embraces the latest trends and inspirations from world cuisines. Today, while dishes like pierogi, kielbasa, and bigos (hunter’s stew) are one you must try while visiting […]

Polish Holidays 2026: A Complete Guide

Poland’s Story of Identity: Heroes, Memory, and Meaning

Attending Catholic Mass in Poland as an American

The Talking Polish Phrasebook

Dictionary of Polish Food