The original Sakha is given for some terms in parentheses.

The Sakha Republic, or Sakha Sire (Саха сирэ), is the largest republic in Russia, more than 4.5 times the size of the American state of Texas. Its territories are a mixture of mountains, broad plateaus, and river and coastal lowlands. Although summers can be quite hot, its winters are the most severe of any permanently inhabited place on Earth. The entire Republic is located in the permafrost zone, making the capital city of Yakutsk the largest city in the world to be built on continuous permafrost.

Pre-Soviet Sakha housing and homesteads were designed to accommodate the traditional seasonal activities of Sakha, which ultimately ensured the survival of the Sakha people.

Historic Sakha Homesteads

Horse and cattle herding are central to traditional Sakha livelihoods. Summers, which can actually be quite hot, were customarily almost entirely dedicated to preparation for the impending winter. From June to mid-August families toiled in the hayfields where they cut, dried, gathered, and stacked fodder for their livestock. Women were also responsible for milking and tending to the cattle as well as gathering and preserving foodstuffs like berries, grains, and wild herbs to fill a family’s winter stores. Men were the primary hunters and meat and fish would be dried and also stored.

Sakha often lived on large expanses of land called alaas (алаас). These homesteads had a permafrost-based ecosystem comprised of a cryogenic lake surrounded by meadows that change to boreal woodlands. Pre-revolution and pre-collectivization Sakha lifestyles revolved around the alaas. Sakha lived in extended clan homesteads on their own alaas where they held separate summer and winter dwellings, kept livestock, and often maintained ancestral memorials like kihi unguogha (киhи уҥуоҕа), a Sakha cemetary, and groves filled with various familial serge, which are wooden posts carved with family insignia, names, and important dates. Few, if any, Sakha now live on their ancestral alaas. Nevertheless many Sakha actively remember their familial alaas and make pilgrimages to them. The alaas remain crucial for Sakha identity formation.

Saiylyk – The Sakha Summer Homestead

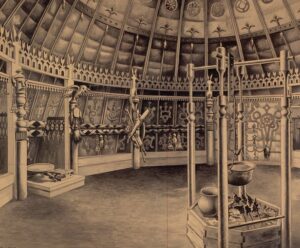

The most ancient known summer home among the Sakha is called an uraha (ураha), a conical tent made from poles covered with birch bark which the Sakha traditionally lived in from May to August in the open-air meadow section of the alaas. Uraha varied in size depending on the number of inhabitants and their wealth and social status. The moghol uraha (моҕол ураhа) was the largest in size, used often by wealthy Sakha to entertain guests. Middle- and lower-class Sakha lived in dallar uraha (даллар ураhа) and the even smaller xhodjol uraha (ходьол ураhа). On the inside of all uraha, the exposed wooden poles featured ornate carved decoration and stained a reddish-brown color using alder extract. In the middle of the floor was an open hearth and above the hearth was an opening in the birch bark, which allowed for smoke to escape and light to filter into the uraha. Bunks lined the inside of the uraha and were used for seating and sleeping. The door to uraha was a softened birch bark curtain. The dirt floor of the uraha, coupled by the airflows created by the conical shape, cooled the interior of the dwelling greatly during the hot summer months.

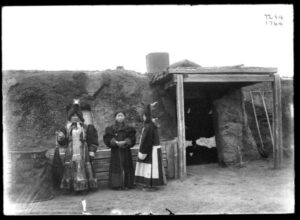

The uraha was common up until the end of the 19th century. Then, due most likely to increasing Russian influence at the time, it was replaced by the saiylyk djie (сайылык дьиэ). This was a log cabin with a flat, grassy roof was the main house in the summer housing complex where families slept, spent time together, and ate. It had a chimney, which most likely connected to a komuluok (көмүлүөк), a Sakha style open-hearth stove, or, later a russkaya pech’ or Russian stove, which is a large stove used both for cooking and heating. Summer mornings and evenings remained chilly and the stove remained important.

Some saiylyk djie had mica windows and most featured an awning on the front where people sat and conversed. This area faced an outside firepit called a kholumtan (холумтан) where people would make offerings to the ichchi (иччи). Ichchi is used to collectively refer to the spirit-masters of things, natural phenomena, and certain places. According to Sakha belief, all of nature is living and thus each aspect of nature has an ichchi. Feeding or making offerings to the fire, called uotu ahaatyy (уоту аhааты), is a central ritual for the Sakha and is carried out before many important events.

The log house was the center of the summer complex, which all together was known as saiylyk (сайылык). To the side of the house was the uut khospogho (үүт хоспоҕо), a small building where milk and milk products were stored. The kitchen was in a separate building called the babaaryna (бабаарына, from Russian поварня, or “cook”), which took the form of a six or eight-sided small log cottage. The ampaar (ампаар, from Russian амбар) or storehouse was where a family kept their foodstuffs like grain, berries, and dried fish and meat. As a rule, the icehouse, called a buluus (булуус), was near the ampaar. Buluus were dug down in the ground until nearing the permafrost. In a well-built buluus, the ice stayed frozen year-round.

Also part of the saiylyk complex, a little ways from the main house and its auxiliary buildings, was the livestock area where there was a titiik (титиик) or an open barn-like shelter similar to a lean-to, and a dal (дал), which was a cattle pen.

All throughout this complex, protecting the family and livestock, small piles of dried manure would be piled. These are called tupte (түптэ) which, when lit, produced billows of smoke that staved off the throngs of mosquitos common in summer in these meadow areas.

Further away from the saiylyk than the livestock area was the family’s haying grounds, called ottuur sir (оттуур сир) or khoduha sire (ходуһа сирэ), which both mean “haying area.” Here men would cut hay using one of two styles of scythe. The first is a sakha xotuura (саха хотуура), a Sakha scythe that slightly resembles a sickle, although its handle is curved and longer. The second is a Russian scythe called nuuchcha xoturra (нуучча хотуурa), which has a much longer handle. Women and children would follow behind the men and rake up the cut hay and stack it in a small pile called a bugul (бугул). Buguls were transported two at a time on a wooden sled pulled by an ox to the area where young men were stacking a massive haystack called a kebihiileex ot (кэбиhиилээх от). Because hay cutting is such a central aspect of traditional Sakha livelihoods, the Sakha language includes very specific vocabulary for every aspect of the hay cutting process. For example, the individual tasked with loading buguls onto the sled is called a bugul ugaachchy (бугул угааччы), the top of the massive haystack is called ot tuhe (от түhэ), and hay rolled into cylinders is called suburgha (субурҕа). Extended kin would assist with this vital, labor-intensive work, a tradition that endures among the waning numbers of families who keep cattle.

Kystyk – Winter Homestead

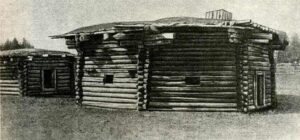

The traditional Sakha winter estate is called the kystyk (кыстык) and was usually located near the forest edge or in the forest itself. The main dwelling, called a balaghan (балаҕан), is a log structure covered in layers of dried cow manure which insulates the house. Balaghans occasionally had mica windows, but most often people would make small panes out of ice, replacing them with fresh panes three or four times during the winter season.

Near every balaghan was a huge stockpile of chopped firewood, which had to be cut, seasoned, and stacked well in advance of the first snowfall in late September or early October. The door of every balaghan was thick, extremely heavy, and well-padded to keep out the cold. By every balaghan door was a large, flat wooden snow shovel. In order to do anything outside of one’s balaghan – tend to the livestock, use the outhouse, get ice to melt for water, etc. you had to be prepared to shovel your path through the thick blankets of snow.

Close to the balaghan was the cowshed, called a khoton, which, like the balaghan, was insulated with layers of dried manure. Many years ago, khotons were attached to balaghans so that people and livestock would share heat. The kybyy (кыбыы), or hay pen, is adjacent to the khoton for people to easily bring their cows new hay twice daily, and the khahaa (хаhаа), or stable and cattle pen, were on the other side of the hay pen. The kystyk, like the summer saiylyk, also had a separate ampaar, the storehouse, and buluus, an icehouse.

In winter, people would spend the bulk of their time in their balaghan and only leave it for very short periods when necessary. A bench-like structure was built into the entire inside perimeter of the balaghan, which provided seating in the daytime and was converted into beds at night. People slept on animal hide mattresses made from bear or reindeer.

The Winter Hearth and the Importance of Fire

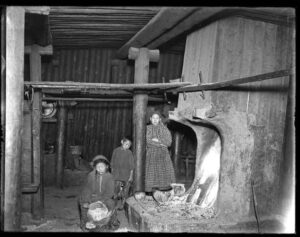

In one corner of the balaghan stood a table where people ate, read, and played tabletop games like khabylyk (хабылык), which consists of throwing and picking up sticks, and baaia (баайа), a game where players bet on a spinning wooden top. This area was generally partitioned from the other side of the balaghan where the komuluok, the Sakha-style fireplace, burned. The komuluok vented through the roof, via a chimney, and had an open hearth called simii ohokh (симии оhох). The simii ohokh was actually fairly poor at retaining heat. However, in winter, the komuluok was the center of all things—it was a source of heat, functioned as a stove for cooking, and served as the site where everything interesting happened. In the evenings, families gathered around the komuluok to chat or do sewing, mending, and other handicrafts. Often, children would play or listen to their elders recite stories and legends.

According to the beliefs of the Sakha Aar Aiyy iteghele (Аар Айыы итэҕэлэ) or Aar Aiyy religion, fire is one of the five realms, or eige (эйгэ). The fire realm serves as a kind of mediator or translator between the higher spirits and ordinary mortals. Legend holds that Urung Toion (Үрүҥ Тойон), the supreme deity in Sakha cosmological belief, had seven sons, the youngest of whom, Tankha Djaralaksy (Танха Дьаралаксы) was the Spirit of Fire. Tankha Djaralaksy bestowed the gift of fire to humankind who inhabit the Middle World and therefore, the spirit of the fire is believed to protect a household from misfortunes and unhappiness. To thank Tankha Djaralaksy and other deities, Sakha often say prayers and give offerings via their fires. Typically this important responsibility fell to the woman of the house who cared for and venerated the fire every day.

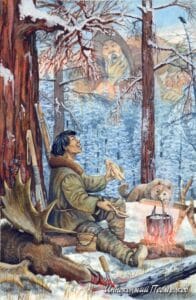

It is also said that long ago before an important event, before traveling or making a big decision, the Sakha would sit before of the fire and listen for a premonition from the spirits. Supposedly, if the fire crackled more than usual, whatever endeavor one was about to embark on was fated to go awry. Sakha also appeal to other gods using fire as a medium. They fed the fire with kymys, fermented mare’s milk, and pancakes called alaadjy, and to cleanse themselves before the hunt, they also burned horsehair and smudged themselves with juniper.

Fire was used to communicate with other major spirts as well. Before hunting, hunters will feed the fire and appeal to Baai Baianai (Баай Байанай), the spirit-master of the forest and animals, and the patron of hunters. If a hunter fails to make an offering appealing to Baai Baianai for a successful hunt, or if they committed a taboo while hunting, bad luck is destined to befall them.

Housing Today

In modern times, the Sakha Republic has undergone urbanization along with the rest of the world; more than 65% of the population is urban.

Housing in modern cities in the Sakha republic are modern constructions. However, in Yakutsk, the permafrost layer is extremely thick, making it difficult to construct large buildings. Before a structure can be built, massive concrete pillars are driven into the ground and are observed for a number of years. If, after a few years, the pillars remain in their original positions, construction can continue. However, if the pillars moved, are uneven, or as can sometimes happen, are in drastically different positions, there is little hope of carrying on with construction.

In the city’s center, most Sakha live in apartments. While it seems that new apartment complexes are constantly being built, Soviet-era Khrushchyovkas, the inexpensive pressed concrete or brick three- to five-floored apartment buildings built in the 1960s, and Brezhnevkas, low-cost buildings of nine to seventeen floors built in the 1970s and 1980s, are still very commonplace.

The further from the city center you go, the more often you will see small, single-family houses. In the suburbs of Yakutsk, single-family homes can be quite large. Many are new constructions using industrially produced imported precut timber, cement, concrete, insulation, and metal and/or plastic siding. Some families also have adopted the Russian custom of having a dacha, a small cottage in the suburbs or the countryside.

In rural areas, very few Sakha maintain traditional seasonal homesteads. Rural families usually have a home they live in for the bulk of the year. Sometimes it is a Russian-style log house with moss filler for insulation. However, new rural houses are increasingly built with modern materials, as in the suburbs. If a family continues to hold cows, they will often have a khoton near their regular place of residence and a small cottage on the premises of their haying lands where they stay during the haying season. Again, this more in the Russian style, similar to a dacha which can be used for agricultural purposes as the khoton is. Hunters will also have an izba (изба) or log hut tucked away in their usual hunting grounds. And again, an izba is typically regarded as Russian-style.

Today, the remains of the dilapidated pre-collectivization structures that still stand are known as otokh (өтөх), which can be loosely translated as “ruins.” However, some constructions live on, and new constructions sometimes made, often for educational purposes, reminding Sakha of how their ancestors once lived. These traditional domiciles can be found at museums, ethno-parks, and yhyakh grounds. As with national dress, modern yhyakhs facilitate interest and understanding of long-established Sakha traditions. In recent years, many communities have invested in erecting new renderings of these traditional dwellings in their yhyakh areas, often attempting to follow the conventional construction practices as closely as possible. New balaghans and urahas also house art and culture centers. There is yet to be a movement to return to actually living in these buildings as new building practices and materials prove more cost efficient and less labor-intensive.

The traditions alaas estates, although not lived on, still hold great significance for many Sakha, who often know and maintain strong relationships with their birth or familial alaas. According to Sakha belief, if someone is visiting their alaas and the otokh after a long absence, they must carry out a ritual to appease the spirits of the alaas and those who linger in the otokh. Typically, this involves looking at one’s alaas through a hole in a stone, and lighting and feeding a fire in the hearth. If one fails to perform this ritual, they are fated to become victims of the otokh abaahyta (өтөх абааhыта), an evil spirit that resides in otokh. Because Sakha believe that spirits reside in these buildings, it is generally deemed taboo to erect new houses on the sites occupied by otokh. Thus, the otokh are allowed to stand for as long as they can and any new activity is often built around them, often giving them wide space.

Traditional Sakha dwellings were built to provide comfort and safety in the extreme seasons. Today scarcely any Sakha elders who were born on and spent some of their youth living on an alaas remain. Nevertheless, the generations who have only known life in the villages created during collectivization and the cities that have grown since the Soviet era still know their ancestral alaas, which continues to embody important cultural and spiritual significance for Sakha.

More About The Sakha

Dacha and Banya: Day Trip from Irkutsk

Dacha – a summer house with rich cultural and economic history – is an integral part of Russian life. To help students get familiar with its peculiarities, regular visits are organised by SRAS to dachas outside of Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Irkutsk. Here, we asked our students from all of those locations to share their […]

The Surprising Story of Russian Buddhism: Моя Россия Blog

In this text, Tajik blogger Roxana Burkhanova describes, in Russian, the history and current status of Buddhism in Russia. Buddhism is a small but historically important minority faith in Russia, especially in the Southern regions of Tuva, Buryatia, and Kalmykia. The material below details both the challenges that Buddhists have faced in integrating to wider […]

5 Ways To Experience Buryat Culture in Irkutsk

Today there are approximately 500,000 people that identify with the largest indigenous group living in Siberia, the Buryats. The Buryats are a group of people descendent of various Siberian and Mongolian people that inhabited the Lake Baikal area, where most of the ethnic group is still concentrated, with many continuing to engage in traditional ways […]

Christianity and Paganism in Russia: Моя Россия Blog

In this text, Tajik blogger Roxana Burkhanova describes, in Russian, the history and current status of Christianity and paganism in Russia as well as touches upon issues of religious freedom. While Orthodox Christianity is the most popular and politically powerful religion in Russia, pagan traditions still survive and other Christian faiths exist. This is part […]

Tengeri Shaman Center in Irkutsk

Shamanism is the common name for the traditional religions of a number of native Siberian peoples; the word describes a system of beliefs in which a large number of spirits, gods, and ancestors affect daily life on earth and can be called upon and influence by specially gifted individuals called shamans. While groups such as […]