Halloween is seen around the world as an American holiday. While it has gained more global popularity in recent years, it is still really only celebrated in the US, the UK, and Canada. In most other countries, including most Slavic countries, it is regarded at most as a reason to host costume parties or perhaps as an unwanted or even dangerous cultural intrusion.

One of the most interesting things about learning more about other cultures is the opportunity to learn more about your own. Interactions with other cultures can not only give us a view of those cultures, but also the opportunity to see our culture through the lens of another.

The following bilingual text is meant to not only explore cultural differences, but to help you build your Russian-language vocabulary by providing Russian phrases within English text.

Viewing Halloween from the Outside

Every culture is different, and what is acceptable or even fun in one culture can seem вульгарным и оскорбительным (vulgar and offensive) in another. The ideas behind these cultural differences are often very difficult to translate, and instead of explaining something using one word, you must often explain the history or theory behind a concept to make it more understandable. For example, Хэллоуин (Halloween) has long been a staple of American culture. In Russia, however, на него часто смотрят с скептицизмом или даже отвращением (it is often looked on with skepticism or even disgust), because, looking at the tradition from the outside, она воспринимается как одержимая смертью и, возможно, даже сатанинская (it is seen as obsessed with death and possibly even satanic).

Much of Russian folklore and belief centers around protecting oneself from evil and misfortune – by keeping it as far away as possible. Directly immersing yourself in the worst imaginable horrors goes directly against these sensibilities. To illustrate this cultural difference, consider that America has had several horror movies with cult followings produced in every decade since at least the 1950s. Meanwhile, the USSR’s very active film industry only ever produced one true horror movie: Vii, which was adapted from a classic story by Nikolai Gogol. While post-Soviet Russia has produced some horror films, they have remained marginal at the box office. The most successful, such as Night Watch, are often closer to sci-fi, fantasy, or thriller rather than what most Americans would consider horror.

When explaining America’s observance of Halloween to Russians, it’s often helpful to understand the tradition in terms of both its христианских и языческих корней (Christian and pagan roots). It is also helpful to understand the holiday in terms of the widespread folkloric phenomena of пороги и карнавал (thresholds and carnival). Lastly, it is helpful to think about какие ценности несет в себе традиция (what values the tradition now carries) that make it a strong part of modern culture.

In other words, when discussing one’s culture with some from a different culture, it is best to deeply understand your own culture and to be able to see your own culture from outside perspectives.

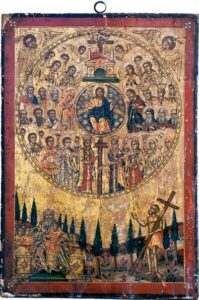

All Hallow’s Eve: The Christian Roots of Halloween

“Halloween” is actually a сокращение (abbreviation) of the name of a religious festival. All Hallow’s Eve is the full name and it occurs the night before All Saints Day – also called “All Hallows Day.” The somber Catholic holiday, День всех Святых – время памяти, почитания и молитвы за тех, кто недавно был принят в рай (All Hallow’s Day is a time to remember, honor, and pray for those who had recently been received in heaven).

Канун Дня всех Святых (All Hallow’s Eve), meanwhile, became a time for remembering all those who had not attained entrance to heaven; it was thought that молитвы могут помочь заблудшим душам пройти через чистилище (prayers could help lost souls pass through purgatory).

Because it was a day when worlds could speak to each other, All Hallow’s Eve was spent praying by graves and at special church services. At night, prayers would be held at the local charnel house – a special place for keeping the remains of those not yet buried or too poor to be buried. Russians also believe that непогребенные не могут обрести покой в загробном мире (the unburied cannot find peace in the afterlife) – at least, not without help.

Halloween as a Threshold

Halloween is thus a порог (threshold). The threshold is a pivotal concept in all cultures, both Christian and pagan. It represents a time or place where there are blurred lines between two things that are thought to be separate, thus allowing a way to pass between or connect them.

The power of Halloween is that it is a time when стирается барьер между физическим и духовным мирами (the barrier between the physical and spiritual worlds is blurred).

The concept of the threshold can be seen across cultures. Many thresholds have been believed in for millennia and deeply ingrained in human belief. For instance, the hour of midnight and the break of dawn are оба примера перехода из одного временного измерения в другое (both instances of passing from one time frame to another). In addition, it is believed that оба времени невероятной силы (both are times of incredible power) in the folklores of many countries, including Russian.

Thresholds represent power but can also represent danger. In Russian folklore, for instance, сохранилась традиция русских женихов переносить невесту через мост (the tradition for Russian grooms to carry their bride across a bridge has been preserved.) The belief began from a fear that crossing a bridge (a physical threshold) on one’s wedding day (a threshold time) was dangerous – and невеста может быть похищена водяными духами, скрывающимися внизу (the bride could be snatched away by water spirits lurking below). There are also many Russian folktales where злой дух прогоняется петушиным криком на рассвете (an evil spirit is chased away by a rooster’s crow at the break of dawn).

In the case of Halloween, the danger comes in the logic that если действия на Земле могут влиять на события в чистилище, то и чистилище может влиять на события на Земле (if actions on earth can affect events in purgatory, then purgatory could also affect events on Earth).

Samhain: The Pagan and Agricultural Roots of Halloween

Many holidays, including Easter and Christmas in the western tradition, include elements of the pagan cultures that preceded the Christian cultures.

Modern Halloween traditions came about from the merging of the traditions of All Hallows Eve and an ancient pagan Celtic holiday called “Samhain.” Самайн включал в себя очистительные ритуалы и акты благодарения (Samhain involved cleansing rituals and acts of thanksgiving). This holiday was one of ritual fires, divinations, and focusing on the power of vegetation. In some ways, it was not unlike the Slavic tradition of Ivan Kupala, although it was held after the harvest rather than after planting.

Samhain came as winter’s approach was eminent. Many cultures developed traditions around this threshold time – when the world was passing from a time of abundant life to a time of cold death. These traditions often благодарили за урожай и с уважением встречали смерть в надежде, что она отнесется к вам с добром (gave thanks for the harvest and greeted death with respect in the hope that it would treat you kindly).

During Samhain, it was believed that души близких могли возвращаться домой, ища гостеприимства (the ghosts of loved ones could return home seeking hospitality). If the spirits were offended, however, they could cause misfortune to come upon the house. Around this belief came traditions of mumming – when people would go door to door, chanting rhymes or songs and asking for food or drink and often while in costume.

This was the beginning of trick-or-treat – and it survived into the Christian era as representative of Christian acts of charity.

Not only the spirits of loved ones, but also spirits in general – both good and evil – also gained power on this night. Going out was considered dangerous and thus protections were developed. The jack-o-lantern was one of these. Although now carved from pumpkins and left on the doorstep or in a window, the jack-o-lantern was originally carved from an easier-to-carry turnip and was used by those traveling at night on All Hallows Eve to light their way and act as a талисман (talisman) to protect them from dangerous spirits.

Another tradition that comes directly from the Celts is bobbing for apples, still often played at modern Halloween celebrations. In this game, яблоки помещаются в ванну с водой, и участник должен достать яблоко, используя только зубы (apples are placed in a tub of water and the participant must retrieve an apple using only their teeth). To protect costumes, a version of this game can be played where apples are hung from strings and must be bitten using only the teeth with no assistance from the hands.

Other modern traditions also continue to focus on agricultural themes – which are common in most ancient traditions. For instance, кукурузные лабиринты вырезаются из частей убранных полей (corn mazes are carved from parts of harvested fields). Similarly, hayrides, where участники катаются на свежем сене в прицепе, запряженном трактором (participants ride on fresh hay in a trailer pulled by a tractor) are popular.

Carnival: Merriment and Troublemaking

Carnival is another concept important to understanding many traditions in many cultures. Карнавал – время веселья, часто с переодеваниями, и время, когда авторитеты, как светские, так и духовные, могли быть поставлены под сомнение (carnival is a time of merrymaking, often with disguises, and a time when authority could be questioned, both secular and spiritual). Sociologists theorize that such times allow “venting” in society and thus actually contribute to overall stability.

Elements of carnival likely existed in Halloween from very early on. Costumes to conceal one’s identity and the presence of “spirits” to otherwise blame for one’s actions likely made such misbehavior tempting. In the Russian tradition, this is perhaps best symbolized in the character of Иван-дурак (Ivan the Fool), a simpleton everyman who is allowed to speak truth to authority because he is regarded as both безумный и божественный (crazy and divine).

Elements of carnival were greatly strengthen in Halloween in the sixteenth century after Queen Elizabeth, then Head of the Church of England, attempted to ban All Hallows Eve. The peoples of Scotland and Ireland, for whom традиция была глубоко укоренившейся частью их идентичности (the tradition was a deeply ingrained part of their identity), responded by making their celebrations even larger and mixing acts of protest with their merrymaking.

The Modern Values Carried by Halloween and Similar Traditions

Today, Halloween is mostly associated with merriment. Many critics of the holiday complain that it is deeply consumerist, encouraging people to buy and consume things that they otherwise don’t really need. While consumerism is undeniably deeply ingrained in American traditions, Halloween also carries other values.

The most important of these are традиции признания и смелости в отношении того, чего мы боимся (traditions of acknowledging and braving that which we fear). Small children are taught on this holiday to not fear the unusual or frightening images around them – that they can be braved and even interacted with. For many Americans, as they grow, this becomes almost a competitive sport – with groups gathering for Halloween to pass through haunted houses or watch horror movies – to be able to take experiences of fright and turn them into exciting jolts of adrenaline.

While Halloween is a distinctly consumerist example, it is directly related to the desire of humans to understand and come to terms with death – one of the most timeless, mysterious, and frightening forces of nature. Other holidays which also attempt to understand, control, or otherwise normalize death have arisen independently across diverse cultures.

Mexico’s Day of Dead is one of the most similar holidays to Halloween, with its roots also embedded in All Saint’s Day. День мертвых (Day of the Dead) is very popular in countries like Mexico, Spain, and Brazil and is even a государственный праздник (state holiday) in those countries. Although similar, including in its widespread use of costumes and imagery featuring death and skeletons, Day of the Dead focuses much more heavily on honoring dead relatives. This is done primarily by maintaining graves and eating at the grave site to share a meal with the deceased. Small gifts and the departed’s favorite food will often be left on a small alter or at their grave.

Qingming in China and many other East Asian countries and Merelots in Armenia also carry these traditions of remembering and honoring the dead by maintaining graves and bringing food into cemeteries to reconnect with the dead across the threshold in the next world.

Conclusion: Halloween in Global Context

Modern Halloween has ancient roots. Many Halloween traditions can be traced back to America’s roots in ancient England and reflect a culture that can question authority, values agriculture, and accepts or tries to accept death as a normal or at least unavoidable part of the cycle of life. However, Halloween, in touching on the subjects of death and evil, can itself seem scary and dangerous, especially to those who were not raised in its traditions. While Halloween is gaining a wider following in Russia, particularly among young adults, many Russians are deeply offended by Halloween’s imagery and traditions. Thus, cultural sensitivity should be used when discussing the holiday abroad.

You Might Also Like

Новый Год по-русски – A Russian New Year: Language Lesson

The following bilingual Russian MiniLesson is meant to build your vocabulary by providing Russian phrases within English text. Hover over the bold Russian to reveal its English translation In most of the Western world, Christmas is celebrated on December 25 and is one of the most popular holidays of the year. Families gather to . […]

Wigilia: Polish Christmas Eve as a Reflection of History and National Identity

By the end of November, the cold cobblestone streets in Polish villages and cities are lined with Christmas markets selling traditional Polish cuisine, handcrafted souvenirs, and traditional amber handicrafts. Christmas is one of Poland’s largest celebrations. The main festivities occur over the course of three days from December 24 to 26. The 25th and 26th […]

Vinegret: The Salad is in the Chopping

While most Westerners know vinaigrette as an oily dressing, often of the raspberry or balsamic variety, in Russia and other countries of the former Soviet bloc, the word has a very different meaning. In these countries, “винегрет” (vinegret) is itself a salad, composed traditionally of boiled, diced beets, potatoes, and carrots mixed with diced pickles, […]

Yhyakh: A Summer New Year in the Coldest Place on Earth

The original Sakha is given for some terms in parentheses. Photographs provided by Mitrofan kyyha Varvara Egorova-Dygyia, Susan Crate, and Kathryn Yegorov-Crate. Yhyakh (ыһыах) is the Sakha people’s annual summer festival during which Sakha make offerings to sky deities known as aiyy (айыы) and make merry before the laborious hay-cutting season. Yhyakh is often rendered […]

Maslenitsa: Student Observations

Maslenitsa is ancient holiday that still takes many Slavic nations by storm every spring. Celebrations are held to mark the imminent end of winter with mountains of hot, delicious blini and revelry. Originally a pagan holiday celebrated as early as the 2nd century A.D., Maslenitsa has been somewhat folded into Orthodox Christian traditions and is […]