The history of coffee in Russia has long reflected the country’s wider history. Originally a western import brought by Peter the Great, coffee culture has risen and fallen with the country’s revolutions and wars, and with its economic developments and collapses. Today, an increasingly thriving coffee culture can be found across Russia as record amounts of bean are imported and a range of shops and chains specializing in espresso-based drinks rapidly grow.

The Coffee of the Tsars

The history of coffee in Russia is traced back to Tsar Peter the Great, who discovered the bitter drink in the Netherlands and brought it home for his people in the early 18th century. Its initial reception was not favorable – many aristocrats called it “dirty syrup.” Nevertheless, Peter served the drink frequently at his court in St. Petersburg. Eventually, as is often the case for coffee, people began to acquire a taste for it, and it slowly evolved into an accepted alternative to, although never as popular as, tea.

Tsarina Anna Ivanovna, whose reign came shortly after Peter’s, also appreciated the drink, reportedly drinking a cup of coffee every morning. Russia’s first coffee house, called “Четыре фрегата” (Four Frigates) opened in the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg in either 1720 or 1740 – which would put its founding under either Peter or Anna, but the sources differ on the date. Opened in large part to welcome sailors from the Netherlands who frequented St. Petersburg, it was named for a celebrated Russian military victory in the Northern War (1700-1721), when Russian ships were able to board four enemy frigates near the Swedish coast. A Petersburg-based coffee brand bearing this name can be found in Russia today.

Catherine the Great also was said to have enjoyed coffee for the caffeine as well as its warm bitter flavor. In fact, Catherine loved very strong coffee – one source notes that she would instruct her cooks to brew 400g of ground coffee for five cups. This is about 10 times stronger than most American coffee today and would have likely resembled espresso.

Throughout the eighteenth century, coffee remained somewhat rarer than tea, and was still a luxury only afforded by the upper class. Typically, the coffee from this time period was imported from Africa – the birthplace of coffee. Unfortunately, Russia’s conflicts with the Ottoman Empire, collectively known as the Russo-Turkish wars, helped physically block Russia from many African trade routes, making coffee scarcer. Meanwhile, the Franco-Russian war boosted the popularity of coffee in Russia in the 1700s. Many of the Russian soldiers who had fought Napoleon came to love coffee while abroad. Upon returning home, many sought it out and began to establish its nascent popularity amongst the middle class.

Throughout the eighteenth century, coffee was still a luxury only afforded by the upper class. Typically, the coffee from this time period was imported from Africa – the birthplace of coffee. Unfortunately, Russia’s conflicts with the Ottoman Empire, collectively known as the Russo-Turkish wars, helped physically block Russia from many African trade routes, making coffee scarcer. Meanwhile, the Franco-Russian war boosted the popularity of coffee in Russia in the 1700s. Many of the Russian soldiers who had fought Napoleon came to love coffee while abroad. Upon returning home, many sought it out and began to establish its nascent popularity amongst the middle class.

Coffee and other imported luxuries such as tea and tobacco become relatively well known, if not widely available or affordable. Consumption of these imported goods became symbols of living a well-off life and they increasingly served as symbols of such in the art and literature of the time. One particularly early and striking example of this comes from Gavrila Derzhavin, noted statesman and poet, who wrote in his 1782 Felitsa:

And I, having slept until noon,

smoke tobacco and drink coffee.

Turning everyday into a holiday, I

circle my thought in chimeras.

As the 1800s progessed, Russia experienced unprecedented economic growth and integration with world markets. As coffee imports edged up, the famous Tula samovar makers began also making coffee services. These were similar in appearance to samovars, but were heated by an alcohol burner from beneath rather than the regular and much higher-temperature pipe filled with hot coals or embers inside the tank. Various publications also turned their attention to coffee recipes, recommending mixing coffee with various liqueurs or floral extracts such as rose hip, orange blossom, or lavender. Buttered and salted coffee seems to have also been popular.

As the years progressed, however, the rarity of coffee did not really change. In contrast, tea became much more readily available. After the 1917 Revolution especially, Russia became almost “tea-total.” In addition to the rarer Chinese tea, several of the Caucuses regions, including Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Krasnodar, began producing (a lower quality) tea of their own. In addition, Ivan Chai, a Russian brew made primarily from fireweed collected in Russia’s wide forests, was also common and also sometimes exported. Meanwhile, nowhere in the Russian Empire can coffee be grown, as the plant requires a very specific climate.

Coffee Supplies in the USSR

After the revolution, Russian coffee consumption practically disappeared. In 1913, about 12,500 tons of coffee was imported to Russia (about 72 grams per capita). In 1938, this had recovered to only about 1200 tons (about 7 grams per capita). At first, the reason was simply the ruined economy, which made imported luxuries less accessible to all. However, the trend continued because the communist command economy prioritized importing industrial equipment over consumer goods like coffee, which were then seen as a bourgeois luxury.

Demand remained, however. In St. Petersburg, a famous café called “Nord” survived the revolution and continued serving coffee, although it was considered a grand luxury. In Moscow and St. Petersburg, the coffee kept flowing in similar locations of pre-revolutionary luxury such as the Eliseevsky Grocers.

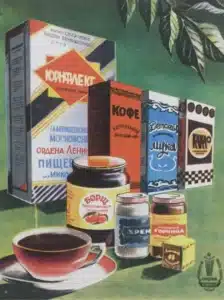

Surrogate versions of coffee abounded. Ground chestnuts, acorns, chicory, barley, and buckwheat were all used to create various recipes approximating coffee. Interestingly, these surrogate versions, particularly chicory, were also commonly served to Soviet kindergarteners. The surrogates would sometimes be sold as “coffee drinks” when mixed with a little instant or even ground coffee (usually imported from India or Brazil).

Perceptions of coffee began to change around WWII, when coffee was supplied by the government to the troops, and particularly to pilots who, it was felt, would benefit from the increased attention and energy.

Supplies of real coffee began to grow after decolonization and accelerating development in the “third world” meant that many countries, some of them coffee-producing, were now looking to import cheap arms and industrial machinery. The USSR had both to sell and often bartered them for locally-produced goods, including coffee.

Thus, in 1959, coffee imports suddenly surged to about 13,000 tons, abruptly restoring and surpassing the height of tsarist-level imports. Coffee imports maintained a relatively consistent climb until about 1975, when they hit a peak of 60,000 tons and then plateaued. In 1989, however, even with the country’s economic and political systems on the verge of collapse, the government still managed to import a sudden record surge of 113,000 tons of coffee. This translates to about 358 grams for every man, woman, and child – enough to make about 30 “double small” coffees for each by the Soviet standard of 12 grams per cup.

How Coffee was Consumed in the USSR

As supply rose, the Soviets looked for ways to integrate more coffee into their centrally planned economy. In the early 1960s, the Hungarian People’s Republic, then part of the Soviet bloc, began to produce Omnia espresso makers for the first time. In 1963, the first maker reached the USSR. It was installed in St. Petersburg, which was then still considered to be Russia’s true coffee capital. Specifically, it was located in the Eliseevsky Grocer on Malaya Sadovaya, a part of town known for intellectuals and artists. In 1965, the USSR opened Shokolodnitsa in Moscow, its first attempt at a modern, European-style coffee house. Omnia espresso makers were used there as well. Shokolodnitsa has survived today as a privately-held chain and remains Russia’s best-recognized coffee-related domestic brand.

Espresso-based drinks remained, however, a delicacy mostly available in Russia’s capitals or major port cities. Most of the country remained drinking either instant or coffee surrogates. To supplement this, the USSR’s first domestic production of instant coffee was begun in Dnepropetrovsk in 1972, using the rising imports of beans. It would soon spread to other Soviet cities as well. Most, however, continued to seek out Indian or Brazilian imports as by-far the better quality instant crystals. Roasting facilities were founded too to produce fresh coffee, although it was generally agreed that imported roasts were better.

Interestingly, production of canned sweetened condensed milk with coffee was also begun – and can still be found on store shelves today. This could be added to coffee surrogates to achieve a more authentic aroma. But this was also never particularly popular.

The 1970’s also saw the beginnings of home brewing start to develop. There were several brewing methods produced – from geyser brewers to filter coffee machines – but most of these were either rare or extremely rare. Most commonly, home brewing was done with an ibrik – a Turkish brewing pot. Very finely ground coffee was added to the ibrik with cold water and then heated to boiling, usually over the gas flame which was most common in soviet kitchens. The result was one to two very small cups of fairly strong coffee whose grounds had to be sipped around as the coffee was drunk.

Coffee after the USSR

The collapse of the USSR led to a collapse of coffee imports as the economy struggled. In the crisis year of 1998, for instance, just five tons were recorded as entering the market.

The 1990s were still marked by the prevalence of instant coffee – although the standard quickly became Nescafe as the giant western company moved quickly to enter and dominate the new market. Foreigners were also instrumental in opening what would be some of Russia’s first true coffee chains: Coffee Bean in Moscow and Traveler’s Coffee in Novosibirsk, for instance, which have both survived through today. For more on Russia’s current large domestic coffee chains, see this article on PopKult.

As Russia’s economy recovered in the 2000’s, coffee imports suddenly recovered in 2008, returning the levels of the mid-1970s, and have grown rapidly ever since. By the mid-2010s, Russia was importing a record 160 tons of coffee annually. Volume and availability again caused the economy to shift to absorb more of the product in diversified ways. This time, however, the result was local chains and specialty roasters.

In the coffee world, the shift that occurred in Russia at this time is part of the “three waves” of coffee history. In the first, coffee is rare and often drunk more for energy, stimulation, and focus. The caffeine, not the taste, was the main reason to consume it. In the second wave, coffee culture is popularized by chains producing espresso based drinks, often sweet, milky, or refreshing, on a large scale. Coffee then becomes consumed for the taste as well as its effects on the body.

As the second wave of coffee made its way to Russia, it became apparent that its success and expansion were rooted in reverence for western brands, particularly after the arrival of Starbucks in 2007. Irina Blank, training manager at Double B Coffee and Tea in Moscow, notes that during this period, “It was fashionable and if you were drinking coffee from Starbucks, you were automatically cool.” Although this sentiment may not have held true for everyone, Irina notes that younger people were the ones being drawn to this style of coffee because “Drinking coffee was seen as cool because tea was so common and [seen as] for parents.”

The third wave in Russia is only just starting. The defining characteristic of this period is the use of lighter roasted, specialty grade (Arabica) coffee beans. Baristas use these beans to manually brew single cups of coffee and pull nuanced shots of espresso. These methods produce drinks that are increasingly sought after and discussed in a way not dissimilar to conversations about wine.

Drago Lakic, director at Soyuz Coffee Roasting, estimates that there are over 150 specialty coffee roasters in Russia today – companies that are using specialty grade beans and paying close attention to the intricate details of their roasts. This is seen especially in bigger cities. Five years ago, for instance, St. Petersburg only had two specialty coffee shops. Today, it has more than thirty. Additionally, Russia has now developed into the eighth largest consumer of coffee in the world, importing about 1.5 kilograms of coffee per capita.

Anastasiya Chekhovich, Head of Sales at Laboratoria Coffee Roasters in Moscow notes that customers’ attitudes towards coffee have also developed. She notes that, “The size of a normal cappuccino changed from 300 ml to a 180 ml (a less milky, more espresso-forward version). It used to be ‘is this coffee is good? It’s from Italy!’ then ‘this coffee is good, it’s Arabica.’ And then it was ‘this coffee is good, it’s Ethiopian.’ Now, people ask where the coffee is from.”

Filter coffee, many Americans may be surprised to hear, is only now really beginning to make its way into the Russian coffee scene. Something traditionally referred to as “watered-down coffee” is now growing into one of the best ways to taste the distinct and nuanced flavors of specialty beans. Many places offering it are often American-branded diners or high-end, Russian-owned shops such as Skuratov Coffee and ABC Coffee Roasters – businesses aiming to offer the types of drinks and service found within third wave shops.

Conclusion: Russia’s Growing Coffee Culture

Since 2014 especially, Russia’s coffee scene has exploded with new brands and formats. Even provincial cities are now dotted with convenient places to get a decent cup of coffee. Store shelves everywhere offer a range of brands and brewing methods. And, in larger cities, a growing number of specialty third-wave shops and roasters are catering to an increasingly coffee-literate population. These shops are a perfect example of how the Russian coffee scene is evolving – embracing the third wave and making it their own.

You Might Also Like

Fitness and Health in the Russian Language

In recent years, gym and fitness options have proliferated across Eurasia. Travelers interested in maintaining their fitness regimen while abroad – whether they are visiting Latvia, Georgia, or even Kyrgyzstan, should have no problem doing so. It does help to know a bit about these gyms and it pays to know some of the Russian […]

Russian MiniLesson: The Russian Soul and Related Russian Vocabulary

Many well-known people from various countries have acknowledged that Russia and the Russians have unique features that can be difficult to explain. For example, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill once said that “Россия – это головоломка, завернутая в тайнувнутри загадки” (Russia is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma). A part of this mystery is […]

Russian MiniLessons: Death in Russian Folklore and Culture

The following bilingual Russian MiniLesson is meant to build your vocabulary by providing Russian phrases within English text. Hover over the bold Russian to reveal its English translation. Russians are often superstitious and regard discussions of death or illness as unpleasant or even dangerous. However, as with all cultures, death does play a significant part […]

The Language and History of Caviar: Olga’s Blog

Olga below describes the place of caviar in Russian food culture. In simplified Russian, she describes where the delicacy is harvested from, the major types of caviar, and how the types differ in cost and quality. We also provide an English primer below discussing more of the history of caviar, how it is eaten and […]

Recommended Books for Learning Russian

From Folkways Editor-in-Chief Josh Wilson: With Internet access and apps now saturating even most of the post-Soviet space, books are becoming somewhat archaic in learning Russian, even for those studying abroad. I remember my new pocket dictionary and copy of 501 Russian Verbs becoming softened and gently stained fairly quickly on my first time abroad. […]