Georgia is home to one of the world’s most diverse selections of native grape varieties. Evidence suggests it’s the oldest winemaking region in the world and it retains unique and ancient winemaking technologies to this day.

Over millennia, winemaking has become deeply integrated into Georgian cuisine, tradition, and identity. It is present at elaborate feasts known as supras and a central theme at holidays like Giorgoba and festivals such as Berikaoba.

Ancient Background: Qvevri

In the autumn of 2017, scientists published findings from an excavation of Gadachrili Gora (გადაჭრილი გორა), a large hill in the region of Kvemo Kartli, just an hour or so from Tbilisi. They detailed a discovery of epic proportions: large, egg-shaped terracotta vessels with archeological evidence of winemaking that is at least 8,000 years old, making Georgia the oldest wine-making country in the world, a title often tugged over with its southern neighbor, Armenia.

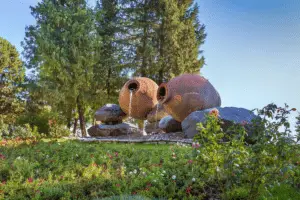

The large amphora-like earthenware mentioned above are known as qvevri (ქვევრი) and remain are a signature of Georgian winemaking to this day. They are recognizable symbols of Georgia and you’ll also notice them plastered on postcards, half-buried in yards as lawn ornaments, and made into tiny figurines for refrigerator magnets and keychain souvenirs.

The uniqueness of qvevri has recently earned UNESCO status as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity; in their designation, UNESCO cites that “wine cellars are still considered the holiest place in the family home” and that qvevri wine making in particular, “defines the lifestyle of local communities and forms an inseparable part of their cultural heritage.”

Made since tools consisted of stone and bone, qvevri production remains a time-honored skill, passed down through generations. For example, in the village of Shrosha, the Bozhadze family still crafts the gigantic clay vessels by hand, shaping them carefully for months before firing them. Qvevri can be commonly found in rural Georgian households, who also devote at least some land to cultivating a private stock of grapes.

Qvevri can be large enough for a grown man to get inside to clean and wax it between each usage. Children are often assigned to smaller qvevri. Shaped like an egg with a pointed bottom and an opening at the top, these enormous clay vessels are filled to their necks with pressed grapes — often including skins, stems, pips, and all. This tendency to use unfiltered grape mash gives many of Georgia’s most beloved wines a deeper, more tannic taste that sets them apart from most other wines you’d find at your local store.

Georgian Wine in Georgian Community and Tradition

Enter many Georgian restaurants you may see a horn or two on the wall. These are khantsi drinking horns. Often embellished with intricate carvings and metal or wood overlays, these are traditionally crafted from ram or goat horns. While the rather unwieldy drinking vessels are rarely used today, what they symbolize is still widely known. In ancient practice, drinking wine from them was thought to confer virility and abundance. The horns are also still recognized as symbols of feasting, hospitality, celebration, and, most important of all, toasting.

Significant life events, holidays, and other important occasions are often marked in Georgia with a supra. Supras (სუპრა) are large, formal dinners with an array of foods and, of course, wine. What really sets the supra apart is the presence of a tamada, or toastmaster. The tamada guides the festivities with a series of toasts, injecting wisdom and humor at regular intervals, drawing everyone’s attention back to reason they are gathered, and drawing the smaller groups of chatting dinner guests back to a single group for a moment, to raise a glass together in celebration.

The tamada is a revered position in Georgian culture – so much so that you will find a handful of statues celebrating the craft scattered around the country. These are almost always carved in a primitive style, reflecting how ancient the tradition is and how deeply it is ingrained in local tradition. Also of note is the khantsi drinking horn the tamada is nearly always shown holding. The khantsi in Georgia is almost always filled with wine.

Recent History: A Wine Variety Revival

Georgians have fought long and hard to preserve their cultural heritage. They have spent most of their long history living under various empires that threatened most, if not all aspects of Georgian identity. Viticulture came under focused attack by the Soviets, who ushered in a period of rapid, forced industrialization across the country that took a serious toll on rural agriculture and village life.

During these efforts — much of which were spearheaded by Stalin’s notorious five-year plan for industrialization and collectivization in the late 20s — most qvevri were dug up and replaced with steel vats. Meanwhile, quaint family wineries were absorbed into sprawling kolkhoz, collective farms which delegated which types of grapes could be cultivated. Many rare indigenous varieties were lost in favor of better-known grapes that grew more efficiently and could be more effectively marketed across the USSR and beyond.

Despite these losses, today Georgia boasts more than 500 varieties of indigenous grapes — around 15% of the world’s total grape varieties in a country smaller than West Virginia — with many winemakers dedicated to reviving rare and endemic grapes.

Quintessentially Georgian Wines

The world of Georgian wine is a big one, and determining where to start when it comes to sipping a glass of your own can be quite the task. Here are two (of many) that embody the essence of Georgian wine.

Saperavi: Saperavi is a Georgian red on max volume — midnight-purple, full-bodied, bold yet crisp, and firm on the tannins. In Georgian, the word Saperavi (საფერავი) means to dye; it also falls in the category of wines sometimes referred to as shavi (შავი), the Georgian word for black due to its deep purple color. Sometimes made by qvevri, sometimes not, it’s always best to order the qvevri option for an even fuller flavor. Enjoy with charred mtsvadi (მწვადი), aka Georgian kabobs, or a hearty stew like chashushuli or kharcho.

Kindzmarauli: Another crowd pleaser is Kindzmarauli (ქინძმარაული). This semi-sweet dark ruby wine comes from the Kindzmarauli microzone of the Kakheti region and is also crafted from the Saperavi grape. Its fermentation process is stopped early to retain more of its natural sugars, giving it a distinctly sweet edge beneath its tannins. With tastes of dark berries with subtle spice and chocolate notes, Kindzmarauli pairs exceptionally well with grilled or roasted red meats, hard and semi-hard cheeses, and fruit-based desserts.

Rkatsiteli: Often vinified in qvevri, Rkatsiteli (რქაწითელი) is known and loved for its amber color and rich flavor, both brought on by its fermentation in the ubiquitous clay vessels buried deep underground. Think apricots, walnuts, and just a teeny bit of spice; that’s the average Rkatsiteli. Enjoy it with a classic Imeruli khachapuri or any of Georgia’s infinite walnut-based dishes, like badrijani nigvzit (ბადრიჯანი ნიგვზით), eggplants smothered in a garlicky walnut paste, or satsivi (საცივი), a cold chicken soup stewed in a delicious walnut sauce.

Speaking of walnuts — don’t forget to try other wine-adjacent delights like churchkhela, a traditional Georgian treat made from a string of nuts smothered in a paste made from grape juice and flour. For the still more adventurous, try pairing a dark Georgian wine with dambal’khatcho, a strong, aged, molded Georgian goats-milk cheese. For something even stronger and wine-adjacent, down a shot of chacha (if you dare), a stout local spirit made from the leftover pulp of winemaking.

Seeking Out Georgian Wine in Georgia

For those looking to taste Georgian wine around Tbilisi, the capital is loaded with places for degustation such as 8,000 Vintages, Vino Underground (Tbilisi’s first natural wine bar), and G.Vino. That said, the most ideal way to experience Georgian wine is to get out of the city and visit a winery firsthand.

Head east for Kakheti — Georgia’s prime winemaking region, or in other words, the wine country within the wine country — to experience delicious wine, creative plates, and warm company at Togonidze’s, sample sacred wines at Alaverdi Monastery where the clergy are helping restore monastic winemaking, or embark on a tour or tasting at any of the countless wineries that dot the countryside. Kakheti is certainly the most popular wine destination, though other popular regions for wine tourism include Imereti and Racha.

For a truly immersive and informative experience, set off with Daria Kholodilina, founder of Trails and Wines, an expert on Georgian wine, and well-known both inside and outside the country. Trails and Wines combines the very best of rural Georgian life — stunning scenery and slow, traditional winemaking. No ordinary tour guide, Daria has made it her mission to preserve and promote traditional winemaking in Georgia and has been widely hailed for her contributions to the industry.

Autumn brings with it Rtveli (რთველი), a festival that surrounds the harvest season. Taking place usually around late September or early October, depending on the region, Rtveli is a prime time to explore the countryside and participate in the many harvest festivities you’ll find there — stomp grapes, sing songs, and feast properly.

Also, know that Georgia’s wine traditions extend deep – you’ll also find very good, often young wines, sold at roadside stalls by families sharing their home traditions and by many local restaurants that ferment them onsite and serve them as house wines. These are also part of Georgia’s extensive wine culture and deserve to be tried.

Georgia cannot be understood without understanding its food culture. Its unique dishes and flavor palates, its boisterous traditions of hospitality and feasting, and its ancient traditions of preparing food and drink are strong strands of the Georgian identity. Wine runs a foundational thread through all of these.

You Might Also Like

Nadugi: Never Too Much (Georgian) Cheese

Dr. Michael Denner: You can tell a lot about a cuisine and culture by the way they eat their milk… That’s the point I tried to make in our latest Georgian Cooking Club meeting, waving about a gallon of milk, sheathed in its translucent plastic carapace. My students were confused at first… Georgian Milk Milk. […]

Berikaoba: Georgia’s Spring Festival Rises Again

Berikaoba is defined by its monstrous-looking masks, good-natured pranking, games and performances of strength, freely shared food and wine, and general festive atmosphere. Although the festival was nearly lost to the passage of time, locals, foreigners, and Georgians from other corners of the country now flock to the Kakhetian villages of Didi Chailuri and Patara […]

Podcast: What Makes Georgian Food Georgian?

What makes Georgian food Georgian? How does the development of Georgian cuisine reflect historical events, geography, and politics? Where do you find the best food in Georgia? In this podcast, Dr. Michael Denner, professor of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies at Stetson University, discusses traditional Georgian foodways, answering these questions and more. Dr. Denner […]

Lobio with Vinegar (Georgian Red Bean Salad)

The following is an excerpt from “Лобио, сациви, хачапури, или Грузия со вкусом“ (Lobio, Satsivi, Khatchapuri, or Georgia with Taste) by Tinatin Mzhavanadze, a best-selling cookbook author in Georgia. It has been translated and adapted by Dr. Michael Denner of Stetson University in Florida. History and Preparation of Lobio Dr. Michael Denner: Lobio (ლობიო, лобио) means […]

Tarkhun: An Incredible, Natural Soda from Georgia

Tarkhun (тархун) is a carbonated soft drink made from tarragon leaves. The drink is known for its typically distinctive green color and is especially popular in Russia and the Caucasus. Tarkhun was first concocted, like most western sodas, by a pharmacist. Mitrofan Lagidze, a Georgian, first mixed carbonated water with his original tarragon syrup in […]