Dr. Michael Denner: For a lot of Georgians, satsivi is… the essence of Georgian home cooking. It is intensely nostalgic, served as the main dish for celebrating the new year, at home, with friends and family gathered around the banquet table, the supra.

SRAS: Dr. Michael Denner is a professor at Stetson’s Program in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies (REEES). A food enthusiast, he is currently translating and adapting a cookbook called Лобио, сациви, хачапури, или Грузия со вкусом (Lobio, Satsivi, Khatchapuri, or Georgia with Taste), by Georgian author Tinatin Mzhavanadze for English-speaking audiences.

As part of this project, Dr. Denner is leading a Georgian Cooking Club at Stetson to test the recipes with Stetson’s diverse student group. He will also be sharing some of the recipes on our site in advance of publishing the book. Most pictures here are from the cooking club’s experience.

Dr. Denner will also be leading Georgian Foodways for SRAS a new, two-week study abroad course that will address topics such as climate change and state agricultural policies within the context of broader issues of food security, the place of food in social justice and ethnic identity, and the role of Georgian foodways in the current global tourism economy.

Preface

Dr. Michael Denner: My cookbook collaborator, Tinatin Mzhavanadze, exemplifies a classically nostalgic attitude to cooking in the introduction to her recipe:

| Tinatin Mzhavanadze (as translated and adapted from the Russian by Dr. Michael Denner): | Tinatin Mzhavanadze (original text): |

| If someone were to tell me that my mom’s way of making satsivi in any way departed from the sacred truth, well, I’d immediately dive behind the barricades and open fire to my last bullet… First off, my mother was a biologist, and I bring this up because she always approached everything, particularly cooking, with a scientific bent, admitting no deviation from dogma and canon. Secondly, satsivi is a Megrelian dish, and my mother lived for several years in Zugdidi. [Megrelia is a western, coastal region of Georgia with Zugdidi as its largest city and capital. Beginning in the 13th century BC, it was a Greek outpost called Colchis. The region is generally considered the culinary center of Georgia, and is well known for its spicy, distinctive dishes.] If that doesn’t mean something to you, then I’ll tell you that having lived in Zugdidi is a guarantee of authenticity when it comes to satsivi. Thirdly, well, it’s common knowledge my mom’s satsivi is the best ever.

There. I’m out of bullets. |

Если мне кто-то скажет, что мамин способ приготовления сациви в чем-то грешит против истины, то я сразу возведу защитные бастионы и буду отстреливаться до последнего патрона. Во-первых, моя мама – биолог. Это я к тому, что она ко всему на свете и более всего к приготовлению пищи подходит строго научно и не признает никаких отклонений от догм и канонов.

Во-вторых, сациви – это мегрельское блюдо, а моя мама несколько лет прожила в Зугдиди, и если это вам ни о чем не говорит, то это такая же гарантия аутентичности в отношении сациви, как рутешествия Карлоса Кастанеды по отношению к его специфической теме. Ну и в-третьих, общественное мнение единодушно признает, что такого идеального сациви, как у моей мамы, просто не существует. Патроны кончились. |

Dr. Michael Denner: OK. In writing about satsivi, I’m apparently wandering into a combat zone. I’ll proceed with all due caution… What I am about to say about the dish might not please everyone. Maybe I should put on a bullet-proof vest…

First off, what is it? Satsivi is, simply, boiled fowl served in a walnut sauce. Most often now the bird is a chicken, though traditionally it’s a turkey, especially if it’s served on New Year’s Eve. (Georgians celebrate New Year’s Eve as a major holiday, a legacy of its history in the U.S.S.R.)

Satsivi is a buffet dish, something you make to serve a crowd. It’s normally served room temperature, like almost everything on the supra table. If however it’s cooked in a k’etsi, in a traditional Georgian micaceous-clay earthenware dish, then it will remain warm (around 125*) on the buffet table for hours. Many cooks now serve it cold. I like it best at room temperature.

Satsivi is delicious, I think, served on a bed of gh’omi (Georgian corn porridge): A gritty white mound of steaming gh’omi, a few pieces of chicken or turkey pushed to the side of the plate, a creamy pool of walnut sauce fills the plate to its rim. With some crunchy Georgian fermented red cabbage on the side.

Here’s Tinatin’s recipe, adapted for the American kitchen by me. Tina starts with a whole chicken or turkey, but I prefer chicken thighs, which are cheap and nearly impossible to overcook.

The proportions are important: Equal parts meat and onion, and half the weight of walnuts. So, if you start with a ten pound turkey, use roughly ten pounds of onion (a lot, I know!) and five pounds of walnuts.

Please send all criticism to my publisher.

Tinatin Mzhavanadze: Satsivi (English)

(as translated and adapted from the Russian by Dr. Michael Denner)

Ingredients:

For 10 servings

- 2 pounds skinless chicken thighs

- 4 cups chicken stock

- 1 large bunch of fresh cilantro (around 3 ounces), the stems separated from the leaves

- 1-2 bay leaves

- 1 pound walnuts (halves and pieces, it doesn’t matter)

- 1 tablespoon ground marigold (or substitute 1 teaspoon turmeric)

- 1 tablespoon mild, dry, ground red pepper (like ancho or Aleppo)

- 1 tablespoon of finely-ground fresh black pepper

- 1 heaping teaspoon of ground coriander seeds

- Ground cinnamon, cloves (a few pinches of each)

- 1 clove of garlic, finely minced or pounded in a mortar and pestle

- 2 pounds onions, finely chopped

- 1 teaspoon brown sugar

- 1 tablespoon white wine vinegar

Preparation:

Place the chicken thighs in a large stock pot and add the stock. If the stock doesn’t cover the chicken, add some water to cover. Add some salt and a bay leaf, and the stems of the cilantro. Over high heat, bring the pot to a boil. Simmer over low heat for ten minutes, then remove the pot from the heat. Set it aside to cool.

Chop the cilantro leaves coarsely and place them in the middle of a 5-inch square piece of cheesecloth. Twist the cheesecloth closed over the cilantro, like a beggar’s pouch, and squeeze the package over a small glass bowl. You’ll be surprised by the amount cilantro juice you produce! Set it aside.

Make the walnut sauce. In a food processor, reduce the walnuts to a fine powder. Add the marigold or turmeric, the black pepper, a substantial pinch of ground coriander seeds, a little ground cloves, and a little cinnamon. And finally, add the cilantro juice and garlic. Process the mixture with two or three pulses of the processor. (This new-school version with the food processor is simple and really easy, though traditional Georgian cooks would scoff and only use a hand-turned meat grinder, or, the ne plus ultra of the Georgian kitchen, an old mortar and pestle.)

When the stock is cool, skim off as much of the fat that has risen to the top as possible, and set it aside. With tongs, remove the chicken thighs and put them in a large bowl, with some of the stock to keep them moist. Cover and refrigerate the chicken. Strain the stock through a fine-mesh strainer or cheesecloth, and set it aside.

In a large skillet, mix the reserved chicken fat (from the stock), the onions, and the brown sugar. If you collected less than two tablespoons of chicken fat from the stock, add a tablespoon or two of butter. Slowly saute the onions over medium-low heat until they are caramelized, deep gold and just turning brown. It’s okay if some of the onions are more done than others, so long as all the onions are cooked until soft and coloring and none of them are burned. The slower you cook the onions, the easier it will be, and the better the results. (This is generally true in life.)

Bring six cups of the reserved stock to a boil over medium-high heat in the large stock pot. (You may have stock left over.) After the stock has reached a boil, turn the burner down as low as possible, wait until the stock is simmering, and add the walnut mix by the cupful to the stock, stirring thoroughly between each addition. Take your time here: Don’t allow the stock to return to a boil, and mix very thoroughly. The sauce should have the consistency of buttermilk or thick cream–in other words, not very thick. Thin the sauce, if needed, with the leftover stock.

Again working in batches, add the caramelized onions, stirring thoroughly between additions. In restaurants, the satsivi sauce is very fine and smooth; I prefer a little texture to the sauce. If you wish, though, you can use an immersion blender to make a veloute-consistency sauce.

Leaving the sauce to simmer over very low heat, tear or cut the chicken pieces into bite-sized morsels. Add the chicken pieces to the simmering sauce and allow the flavors to blend for five minutes.

Add the vinegar and stir thoroughly. Georgian cuisine is characterised by a slight tartness: The vinegar should be present, but not overwhelming. Add a little more vinegar, if you need to. Correct the salt and pepper, remembering that this dish will be served at room temperature or cold, and that cold dishes need a little more salt than those served warm.

If you plan to serve the dish in the next hour or two, just turn off the heat and serve the satsivi, warm. If you’re serving it many hours later, transfer it to a serving dish and refrigerate. You can serve it directly from the refrigerator, or (better) let it warm up on the table for an hour or two before serving.

Serve over steaming gh’omi or polenta.

Tinatin Mzhavanadze: Satsivi (Russian)

Готовится сациви долго, так что отключите телефон, факс, расслабьтесь и настройтесь на подвиг.

Канонический рецепт предполагает индейку. Обычно у несчастных индеек наступает апокалипсис к Новому году: их убивают почем зря, но такова живодерская традиция.

Не будем это обсуждать: нет индейки – берите крупную курицу. Здоровую, упитанную курицу, желательно вскормленную из хозяйских рук отборной кукурузой. Если берете мороженую – все погрешности списывайте на ее нездоровый образ жизни.

Эта кофейная чашечка сока кинзы может вызвать судороги: сначала свежую сочную зелень надо пополоть в ступке, а потом отжать через марлю. Я не смею спорить с мамой, но это у нее пунктик. Впрочем, можете обойтись и без сока кинзы.

- молодая индейка (или курица) – 2 кг

- грецкие орехи очищенные – 500-800 г

- лук репчатый – 1 кг

- молотый имеретинский шафран – 1 ст. ложка

- молотый кориандр – 1 ст. ложка

- молотый черный перец – 1 ст. ложка

- молотая корица, гвоздика, соль – по вкусу

- сок кинзы – сколько получится из большого пучка зелни

- белый винный уксус – 1 ст. ложка

- соль, чеснок – по вкусу

- лавровый лист – по желанию

Приготовление:

Птицу сварите в несоленой воде в большой эмалированной кастрюле, так чтобы она не высовывала свои неприличные голые ноги – разве что самую малость щиколотки.

Внимание: не переварите! Потом вы ее выложите на блюдо, она остынет – на случай, если все-таки переварилась, мясо успеет схватиться и принять четкую форму; потом засуньте ее в духовку для подрумянивания на час при 180 градусах и туда же поставьте мисочку с водой – для сочности мяса.

Теперь выпейте валерьянки (или водки граммов пятьдесят), сделайте вдох-выдох и приступайте к священнодействию.

Остуженный бульон процедите через марлю. Жир соберите, положите на сковородку и в нем, не торопясь, до розового цвета обжарьте 1 килограмм (да-да!) мельчайше нарезанного лука.

Это чудовищно, но искусство требует и не таких жертв.

500-800 граммов максимально светлых грецких орехов (лучше прошлогоднего урожая, в них масла больше) смолоть в пудру и в них добавить: 1 столовую ложку молотого имеретинского шафрана, 1 столовую ложку черного перца, чуть меньше столовой ложки просеянного через ситечко молотого кориандра, 1 кофейную чашечку процеженного сока кинзы.

Еще 4-6 растертых с солью в керамической ступке гвоздичек, на кончике ножа (не больше!) корицы.

Орехи со специями хорошенько перемешать (можно рукой, можно деревянной ложкой), развести в кашицу, влив половник бульона, и добавить 1 головку толченого с солью чеснока.

Еще вариант, когда добавляется еще столовая ложка белой кукурузной муки тонкого помола, но это для густоты и чтобы оттенить вкус специй.

Теперь завершающий этап, когда все наши труды сойдутся воедино и сотворят чудо.

Прочитайте молитву и приступайте.

Бульон – весь не бухните, смотрите, жидко будет, стаканов примерно 6-8, – поставить на огонь, довести до кипения, огонь убавить до микроскопического.

Смесь добавлять в бульон понемногу, перемешивая деревянной ложкой, чтобы не пригорело, не свернулось, не перекипело!

Затем туда же – лук! И помешивайте, помешивайте, медленно, но верно!

Затем туда же – нарезанную примерно равными по размеру кусками птицу.

Когда все это хорошенько закипит, влейте 1 столовую ложку белого винного уксуса.

Можно положить пару лавровых листиков.

Еще пять минут равномерного бульканья на несильном огне.

Проверьте соль-перец и выключайте.

Если вы все еще живы, поздравляю: вы сделали настоящее сациви!

Our Favorite Satsivi Videos

This is a clear, English-language recipe from an amateur cook.

Here, a professional Georgian cook takes you through his recipe in clear, slow Russian (and he introduces it in Georgian).

You Might Also Like

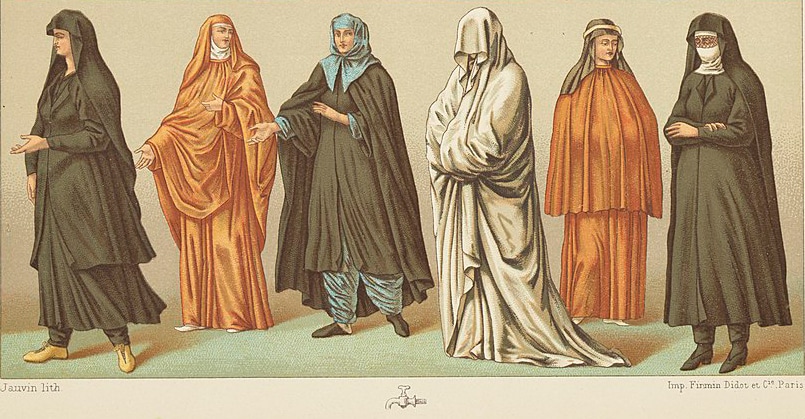

The Talking Phrasebook Series presents useful phrases and words in side-by-side translation and with audio files specifically geared to help students work on listening skills and pronunciation. Each entry below, divided by category, features an English word or phrase in the left column and its Georgian translation in the right. The Georgian is presented in […] Georgian holidays strongly reflect the country’s unique traditions and its demographics. First, as more than 80% of Georgians identify with the Georgian Orthodox Church, the strong influence of the church can be felt in the preponderance of Orthodox holidays. Georgia also has several holidays celebrating its statehood and independence, which have been hard-won. We can […] Fruit leather is simple, ancient food. Like bread and roasted meat, it likely independently evolved in several places. At its most basic, it is simply mashed fruit smeared to a sheet and left to dry in the sun. The result is a flavor-intensive food that travels well and can keep for months. The oldest known […] This guide to travel in Georgia is tailored for Jewish-American university students preparing to study abroad in Georgia. We navigate the historical depth and modern vibrancy of Jewish life in this culturally rich country. Discover key historical sites, engage with local Jewish communities, and find practical tips on maintaining kosher practices and observing Shabbat while […] Despite their cloistered livelihood, nuns have found their way into many veins of popular theater and movies. However, their usual depiction, wearing black habits with a veil and carrying a rosary, is not accurate for all nuns. It is true that the symbolic meaning of the habit is consistent across both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox […]

The Talking Georgian Phrasebook

Georgian Holidays 2025: A Complete Guide

Tklapi, Pastegh, Lavashak: One Ingredient Fruit Leather from the Caucasus

Jewish Georgia: A Brief History and Guide

The Habits of Nuns in Catholic and Orthodox Traditions