Uzbekistan’s ancient pottery and ceramics offer a window into the deep history and vibrant cultural evolution of Central Asia, connecting the ingenuity of early Silk Road societies to modern-day artistic traditions. The remarkable discoveries unearthed by archaeologists, from Hellenistic-era pottery fragments at the Uzundara Fortress to the intricately glazed ceramics of Rishton and Afrasiyab, reveal a continuity of craftsmanship shaped by cultural exchanges and historical transitions. These artifacts not only document the development of pottery techniques and artistic styles across millennia but also highlight the resilience of Uzbek traditions through periods of conquest, globalization, and modernization. Today, the revival of these time-honored crafts underscores their enduring relevance, as both a source of national pride and a draw for international tourism, particularly to Uzbekistan’s major cities, breathing new life into the legacy of the Silk Road.

Archeological Discoveries in Uzbek Ceramics

Through pottery fragments, archeologists have been able to piece together remarkable discoveries about the economy, politics, and daily lives of the societies that made up the Silk Road.

Uzundara Fortress digs have offered the oldest fragments, remarkably preserved by Uzbekistan’s dry climate and dating back to the 3rd century BCE. The fortress, near the Uzbek-Afghan border, served as a military base during the Hellenistic period of Central Asia, soon after Alexander the Great expanded his empire into Central Asia. Storage jars, bowls, flasks and cups found here indicate that people were already using pottery wheels at that time. What the surface design of the pottery might have been is unknown, however, due to the lack of glaze, which would have protected any paint.

Rishton is one of the oldest centers of glazed pottery, which began to be produced around the 8th century. Located in the Ferghana Valley, it was perfectly situated to benefit from both the Silk Road trade flows and the valley’s rich clay deposits, which are of such high quality that they do not need refinement. The clay is also ideal for ceramics because of its iron content, which makes it easy to work with when it is wet and more durable once it has been fired. Further, the richness of local plant life and mineral wealth allowed Rishton ceramics to become known as unique in their use of endemic natural materials for paints and glazes. Most importantly, a glaze called “ishkor” was developed by burning a local desert plant of the same name and mixing its ashes with locally-sourced crushed quartz. Ishkor is an incredibly durable glaze with a subtle blue-green lustre and, unlike some ceramics that were historically made in Tashkent and Samarkand, does not use lead.

Afrasiyab was another hub for ancient Uzbek ceramics. It began to flourish in the 9th century CE, right around the dawn of Islam’s spread into Central Asia. Many of the ceramics archeologists have found at this site, which now lies in ruins outside of Samarkand, are figurines of deities and mythical creatures from pre-Islamic folklore in addition to practical items such as kitchenware.

Throughout Uzbekistan, the style of ceramics was influenced by each historical era, and we can see influences from the introduction of Islam, the Mongol invasion, and the Timurid dynasty. Political fracturing in the 17th century led to three distinct khanates being formed, each of which began to develop its own signature style. After Russian control was established, local ceramic production experienced a decline due to the import of commercial goods from the Russian Empire. It was later revived during the Soviet Union when art collectives were formed. In recent years, traditional ceramic making has boomed thanks to a rapidly increasing number of tourists seeking out these beautiful and unique crafts in gift shops throughout the country.

While cremanics has been a craft traditionally passed down from father to son, today, some artisan families are involving their mothers and daughters as well.

Historical Development of Design Motifs in Uzbek Ceramics

While the painted design of Uzbek ceramics varies greatly across time and place, plenty of specific themes can be identified and studied. Designs can be generally sorted into four categories: pre-Islamic religious motifs, inscriptions, geometric patterns, and plants.

At Afrasiyab, many pieces exhibited an intriguing mix of designs with both non-Islamic motifs such as solar symbols, the swastika, and a four-pointed star interwoven with Arabic calligraphy. This suggests people at that time viewed Islam not as antithetical, but complementary to, their traditional religion, whether that be Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, or Manichaeism. Arabic inscriptions subsequently belonged to two types: barakah (well-wishes) and proverbs regarding morality and wisdom.

The pottery of Khorezm is characterized by its geometric patterns such as the “girih.” Geometric patterns gained popularity in part due to an interpretation of Islam which prohibits the drawing of animate beings. Plant designs, called “Islimiy,” are often incorporated into geometrical patterns as plants are inanimate.

Certain plants additionally serve as symbols, such as:

- Pomegranates – fertility, abundance, wealth

- Chili peppers – protection from evil spirits

- Tulip – the coming of spring

When Chinese goods became abundant in the 14th and 15th century, porcelain inspired the development of a new material-base for pottery called “kashin.” Made of sand and less dense than clay, these ceramics were lighter and more delicate. Additionally, the blue/white duochrome palette and the common imagery characteristic of Chinese porcelain, such as lotuses, clouds, phoenixes and storks, began to appear on Uzbek pottery as well.

Each region had a trademark color scheme. Samarkand pottery typically featured brown or red Arabic inscriptions on a white background. In Gijduvan, a dark green or brown glaze serves as a foundation for simple yellow, green, blue, and maroon patterns.

Glazes were also regional. Samarkand, Tashkent, and Bukhara applied a lead-based glaze that brought out shades of maroon, while in the Ferghana Valley and Khorezm, the ishkor glaze resulted in cool turquoise tones.

How Uzbek Ceramics are Made: Then and Now

At the Rishton Traditional Pottery Center and Gijduvan Ceramics Museum, one can see the entire process of producing pottery – from raw materials to finished product. Both institutions are home to multi-generational family ceramics workshops and preserve pre-industrial production practices.

Preparation of the clay:

- Clay is collected from a depth of 0.5 – 2.3 meters (~1.5 to 7.5 feet) to ensure the best purity, consistency, and moisture content.

- The clay is kneaded by pounding and/or stepping on it repeatedly to remove any air bubbles.

- Once the correct texture and moisture level is achieved, the clay is taken to the wheel. In traditional workshops, the wheel is powered by swinging one’s leg back and forth to kick a platform connected to a vertical axle holding the wheel surface. This allows the artisan to easily control the speed.

- When the shape of the bowl, jug or plate has been achieved, the craftsman adds engravings or imprints with a stick, his/her fingers, or other implement.

- The ceramic object sits for one day to dry.

Preparation of paints and glaze:

- Endless types of paints and glazes are available in the modern era, but traditionally, paint dyes were created using plant sources such as onion peels and pomegranate skins.

- Colored powders are traditionally produced by grinding materials between layers of stone. This was often done on a large scale using donkey-powered mills.

Decorating the ceramic piece:

- A thin coat of underglaze is applied to the outside surface of the object as a base coat to create a white background.

- The clay undergoes the first round of baking, called “khompsaz.”

- After baking and cooling, designs are painted onto the surface of the object and then glazed over.

- The object is placed in a kiln to bake again, finishing the paints and glaze.

Clay and Ceramics in Architecture in Uzbekistan

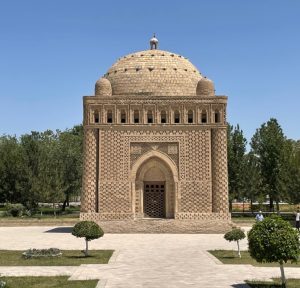

As early as the 6th century, raw clay was used as a building material in Uzbekistan. By the 10th century, the first structures made entirely out of fired clay terracotta bricks were constructed. Baking the clay greatly enhanced its durability, as is evidenced by the Samanid Mausoleum, which stands in practically brand-new condition today more than 1,000 years after it was built. By the 11th century, carved Arabic inscriptions, floral and geometric ornamentations were applied to minarets, mosques and mausoleums. Soon after, newly-developed blue, white and red glazed tiles were used as architectural ornaments.

In the 14th century, a new silica-based material called faience, which had originated in ancient Egypt, became common in architectural facades. The construction boom of the Timurid Dynasty brought carved stone, faience, and glazed clay ceramics together in grand architectural complexes such as the Bibi Khanoum Mosque and Ulugbek Madrasah.

The next few centuries were comparatively unglamorous. The states that succeeded the Timurids were not as strong or wealthy and many buildings suffered damage from earthquakes, looting, and weathering. In the early Soviet period significant restoration work began and, under independent Uzbekistan, restoration work has flourished. Today, these centuries-old magnificent mosques, madrasas, and mausoleums are the country’s biggest tourist attractions.

Production of ceramic tiles:

- A large hole is dug among clay deposits into which water is poured to wash salt from the soil so that salt residue does not tarnish the ceramics and glaze during baking.

- The mound of clean clay is left to freeze over the winter. Doing so leaves the clay looser and easier to work with once thawed.

- Straw and horsehair, which help prevent cracking, are added to the clay.

- The clay is pounded and beaten to remove any trapped air.

- The clay is left to dry out before it is placed in the oven to bake.

- After the first round of baking, the clay is polished, glazed, and then baked once more.

- The finished ceramic is applied either directly to a building wall or to a precut panel which is adhered to the building along with other panels.

Uzbekistan’s pottery and ceramics serve as a vivid reminder of the country’s rich history, reflecting centuries of cultural exchange, artistic innovation, and skilled craftsmanship. From the ancient pottery wheels of the Hellenistic era to the vibrant ishkor glazes of Rishton, these artifacts illustrate how deeply rooted ceramics are in the region’s identity. Today, the revival of these traditional crafts is not only preserving a vital piece of cultural heritage but also fueling Uzbekistan’s growing tourism industry. As visitors flock to the Silk Road’s historic sites and artisan workshops, they help sustain this timeless trade, ensuring that the story of Uzbek ceramics continues to inspire future generations.

You’ll Also Love

Halva, Halwa, Helva: A Hundred Sweets from Dozens of Cultures

Halva, the rich dessert well-loved across many cultures, is so densely filling it almost manages to feel like a meal – and not an entirely unhealthy one at that. There are more than one hundred varieties of halva, an ancient dish whose base can be flour, ground seeds or nuts, or fruit, depending on where […]

Uzbek Holidays 2026: A Complete Guide

Most of Uzbekistan’s holidays are recognizable from the old Soviet calendar, although they have been moved, refocused, and/or renamed to now celebrate Uzbekistan’s independent, post-1991 history and culture rather than that of the USSR. The major exceptions to this are two major Islamic holidays and the ancient Persian New Year celebrations that have now been […]

Baursak: The Donut of Hospitality

Throughout much of Central Asia, one type of bread stands out from all the rest – baursak (баурсак). These small pieces of fried dough are known throughout Central Asia among many of the Turkic and Mongolian-speaking peoples there. In Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan especially, they are served as everyday fare accompanied by tea and are staple […]

Victory Day in Russia and Other Countries: Vocabulary and History

Victory Day is a holiday of significance in many Eurasian cultures, but particularly stands out in Russia. People pay homage to veterans and remember the sacrifices that were made for the sake of victory in WWII. While Victory Day is deeply ingrained in Russia’s national identity, its observance across Eurasia reveals nuanced changes or adaptations […]

Chuchvara, Chuchpara, Tushpara: The Daintier Dumping of Central Asia

Chuchvara is a dumping staple dish in Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the Middle East. Originally introduced there under the Persian Empire, they are today most associated in Central Asia with Uzbek tradition. However, they are also considered a local national dish throughout the countries of the region. Chuchvara contrast with manti, the other […]