Fruit leather is simple, ancient food. Like bread and roasted meat, it likely independently evolved in several places. At its most basic, it is simply mashed fruit smeared to a sheet and left to dry in the sun. The result is a flavor-intensive food that travels well and can keep for months. The oldest known fruit leather traditions hail from the Middle East and may have entered the Caucasus through Armenia, where the food was first recorded in writing in 1227 AD. Today, it is considered to be a fully integrated national dish of Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, where it is known as tklapi (ტყლაპი), pastegh (պաստեղ), and lavashak, respectively.

Why Are They Called Tklapi, Pastegh, and Lavashak?

The word “tklapi” comes from the Georgian verb “tklapva” (ტკლაპვა), which means “to flatten” or “to spread.” This etymology is fitting, as making tklapi involves spreading the fruit puree into a thin layer before drying.

Many other names stem from the Latin word “pastillus,” which is what the Romans called fruit leather. “Pastillus” is often translated as “small bread.” However, the construction of “pastillus,” the root of which also gives us “pasta” and “paste,” actually refers to “a thing made of paste or dough,” which precisely describes fruit leather. Names that can be traced directly back to the Latin include “pastilos” in Greek, “pastegh” in Armenian, and “bastik” in Turkish.

Other names are also often associated with bread – namely lavash, a type of thin flat bread enjoyed throughout the Middle East, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and beyond. Fruit leather is, much like lavash, soft, thin, and pliable – making the name memorable and practical. In Iran and Azerbaijan, it is known as “lavashak” (little lavash). In addition to the Latin-originated pastegh, the Armenians also use the more localized, “sour lavash” (Տուտ լավաշ) and “fruit lavash” (մրգային լավաշ), depending on if the treat is tart or sweet, respectively.

One of these bread names – lavash or pastillus – may have been taken as a translation of the other. Indeed, Rome and Persia had extensive contact over several centuries. However, it is also possible that the food and names evolved independently in multiple places (fruit leather was also eaten by Native American tribes who must have also independently developed it) – and might be as old as the technology of using hot, flat rocks to cook with.

Another interesting naming trope comes from Syria, whose apricot-based fruit leather is sometimes called amardeen (after the apricot it is usually made from) and sometimes Qamar al-Din, which translates literally as “Moon of the Faith.” This name could derive from the fact that the food is heavily associated with the Muslim holy month of Ramada there – and helps to explain why it is common, especially in Muslim-majority Azerbaijan, to sell fruit leather as perfectly round, translucent disks.

How to Properly Eat Tklapi, Pastegh, and Lavashak?

Tklapi, pastegh, and lavashak are all long-lasting, highly portable, and energy-intensive foods. Thus, they are a sustenance of choice for travelers and hikers in the Caucasus. They can also make for a good souvenir to take home.

These fruit leathers are also highly versatile. They are often sold as large, folded sheets. Tourists usually bite directly in, but locals will often roll them and cut them, creating “tapes” for easier eating. In restaurants and homes, they are often served cut into strips and served with wine or tea. They can be used to dress various desserts for presentation and added zest. They can also be made into more elaborate desserts such as by wrapping the leather around nuts or other fillings and/or providing sauces for them such as pomegranate syrup or honey.

Tklapi, pastegh, and lavashak are also soluble. They can be used to flavor tea or, as in Syria, to make a drink like Qamar al-Din, which shares a name with the local fruit leather. Popular during Ramadan, this drink is made by placing the dehydrated fruit in warm water until fully dissolved. The result is a fast delivery system of hydration, sugars, and electrolytes and is invaluable after a full day of fasting.

Solubility also means that they can be added to soups like Armenia’s t’ghit, made by boiling sour plum pastegh and mixing it with fried onions. Some Georgians similarly add that sour plum tklapi to their famous kharacho stew. People in Azerbaijan use strips of sour lavashak, mixed with walnuts and onions, as a traditional stuffing for chicken or fish.

Lastly, tklapi, pastegh, and lavashak can be used for medicinal purposes. Many of the fruits used to make them, such as plum and apricot naturally reduce triglyceride levels, improving liver function. They are also high in vitamin C and, combined with the ability to suck on strips over an extended period, can make them highly effective ways to treat sore throats. Some, such as figs, have natural antibacterial properties and enzymes that promote healing. Fruit leather made of figs can be eaten, of course, but has also been used to help treat wounds.

How to Properly Cook Tklapi, Pastegh, and Lavashak?

Making fruit leather is quite simple. Once the fruit has been chosen, it is boiled to remove some of the water and intensify the flavor. Then, it is blended to a purée and spread on a flat, non-stick surface. Some will use a cellophane or cloth-covered board, or one can use a cookie sheet with a non-stick inlay or even a little taste-neutral cooking spray. Give the bottom of the board or sheet a few solid taps on the table to give the fruit paste a nice, even spread. Most traditional is to then lay this out to dry in the sun, which usually takes a couple of days at least. An alternative is drying it in the oven on low heat for a few hours, or in a dehydrator for up to eight hours.

Despite its ancient origins and wide geographic spread, recipes for all forms of fruit leather tend to emphasize that it can be made as a single ingredient dish. Many recipes will suggest that you can add a small amount of sugar or honey, or mix in other fruit purees such as apple or barberry, to add sweetness, add flavor, or alter the texture – but they most often cite these as options. Truly fancy recipes might suggest spices or even garlic – but again, most recipes from across the Caucasus prefer to keep it very simple.

The most common fruits to use for tklapi, pastegh, and lavashak are also held largely in common. Sour plum and apricot rank at the top as most traditional. Also common are peach, apple, and pear. Some, like mulberry and fig, tend to be regional. In the modern era, however, as global markets have opened to the Caucasus and as chefs have grown more adventurous, varieties such as kiwi, cherry, and feijoa can be found.

One regional difference is that Armenian recipes are most likely to include cornstarch or flour, which acts as an emulsifier, creating a softer, chewier snack.

Most Americans may find pure fruit leather a bit tough as well. Commercial fruit leather began in America at a sweets shop in Little Syria, a neighborhood in New York, that sold amardeen cut from large, thick sheets. It became popular with locals – who dubbed it “fruit leather” for its appearance and tough texture. When this eventually evolved into the Fruit Roll-Ups now populating today’s elementary school lunch boxes, it became thin, individually packaged candies that consist mostly of corn syrup and emulsifiers to ensure a very sweet and soft snack – but one quite different from the original.

Let’s Cook!

Tkemali Tklapi

Ingredients:

- 4 pounds wild plums (scale recipe as needed)

- Add ripe tkemali and a finger’s width of water and boil for about 20 minutes.

- Drain through a colander or purée the mixture in a blender until smooth.

- Wrap cellophane film on a wooden board and spread the batter evenly across the board at a thickness of ⅕ of a centimeter.

- Sun-dry the batter for 2-7 days, turning periodically.

- Roll up the dried tklapi sheets and store in a dry place.

Grape Juice Pastegh

(can substitute other juices)

Ingredients:

- 8 cups fruit juice

- 1 cup flour

- Heat two cups of the grape juice until lukewarm. Add flour to the cup of grape juice and mix well.

- Bring the rest of the grape juice to a boil. Add in flour mixture slowly, stirring constantly until the mix begins to bubble.

- Pour the mixture onto a sheet of muslin or cheesecloth, and let dry indoors for about 12 hours.

- Take muslin/cheesecloth and hang outside from a clothesline. Let dry for 24 hours.

- Lightly spray the backside of the cloth with water to release Pastegh from the cloth.

Video Tutorial

Seva Sevin gives a glowing review of both sweet and sour tklapi, showing a street-bought tkemali tklapi sheet and detailing its texture and taste. The longing gaze her dog gives the fruit leather goes to show the love this dish deserves.

You’ll Also Love

Pickling Russian Style

The process of pickling (соление) is well-known in Russia, and any traveler visiting Russia, Ukraine, or Belarus will undoubtedly come across several traditional pickled dishes that seem strange and exotic. With a relatively short growing season, preserving food has always been of special importance in Russia, where you can easily find pickled cucumbers, tomatoes, mushrooms, […]

Samsa Traditions in Bishkek

I have always admired the “one cook, one dish” tradition. To paraphrase food critic Anthony Bourdain, this is the tradition where one lone artisan, or family of artisans, makes the same wonderful dish year after year, generation after generation, and by doing so, forms a close identification with the dish that ensures it is always […]

Buryat Cooking Lesson at Ulus in Irkutsk

One of my favorite things about living in/traveling to other countries is getting to know the national cuisine. Irkutsk is located right next to the (Russian) Republic of Buryatia, and as such has a large population of ethnic Buryats (they’re closely related to Mongolians). I also love cooking, though with a minimum of skill, so […]

8,000 Years of Winemaking Lives On in Georgia

Georgia is home to one of the world’s most diverse selections of native grape varieties. Evidence suggests it’s the oldest winemaking region in the world and it retains unique and ancient winemaking technologies to this day. Over millennia, winemaking has become deeply integrated into Georgian cuisine, tradition, and identity. It is present at elaborate feasts […]

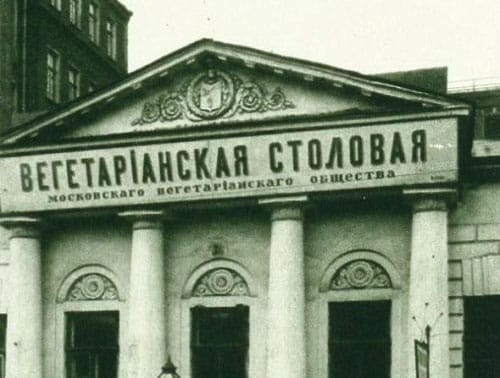

History of Vegetarianism in Russia

The following article originally appeared in Russian on Vegetarianskij.ru. It has been translated and adapted by SRAS for presentation here. History of Vegetarianism in Russia The official coming of vegetarianism to Russia was inaugurated with the opening of the first vegetarian society. This was in Saint-Petersburg in the mid-1860s. The society was humorously called “Ни […]