This is the second of a two-part series. Read part one here

Naryn: Work the System

Some people I talked to suggested that Naryn was the most Kyrgyz of all the provinces. Most of the country’s Uzbek population lives south of this province, and the Russians tended to keep to the northern areas. In fact, much of Naryn’s population was nomadic well into the 20th century, and for good reason. It seemed that there wasn’t a single tree in the province that wasn’t planted and irrigated. The soil is just too rocky. While the mountains around Issyk Köl were full of pine and juniper trees, many of the mountains in Naryn were just as green, just as high, but they only had grass on them.

Suggestion #7: Go with the family connections.

Again, Tynara opened up opportunities for me. Her sister teaches school in Kochkor, a town about three hours from Bishkek, just over the border from the Chui province. We stayed with her family our first night. I learned that we would need a guide and chauffer. The infrastructure in Naryn is very poor; there are some places where the roads actually disappear back into the reddish-brown earth. Whole bridges are just not there anymore. We needed not only someone who knew his way around, but also had the means to drive through small streams, if need be.

The next day I met him: Tynara’s sister’s friend’s husband. He had a Niva, which is the Soviet version of an SUV. I’ve driven in a lot of Soviet cars but this is the only kind I’ve seen that has four wheel drive. During our stay in Naryn, I became very grateful for this man. I became even more grateful for his car: we drove places where I thought only a goat could climb. We wouldn’t have been able to make the trip if it wasn’t for our guide, and we found him through the informal system of connections that almost everyone in Kyrgyzstan has. You can call a tourist agency, but finding guides, places to stay, rides, and even good conversation is easier and more efficient through this informal system. It is also less expensive: the closer the guide is to your original contact, the less you’ll have to pay.

Suggestion #8: Stay in a yurt.

While in Naryn province, we visted Son Köl, a very high mountain lake. There are yurt camps there that will give you a meal and lodging for a price. We stopped at a lone yurt to find a woman baking bread, which consisted of spreading the dough in a flat metal pan, covering the pan with a curved metal lid, and then covering the whole thing with flaming dung. Surprisingly, it could be the best bread I’ve ever eaten—served with strawberry preserves and fresh butter. When eating (or doing anything else) in a yurt, we sat on the floor. This one had a table, but in some yurts there was just a mat on the floor. We ate with our hands, just dipping the bread in the preserves or the butter (although most of the more tourist-type yurts have spoons). We didn’t pay anything for this. The owners were related to our guide.

When we visited Issyk Köl for Tynara’s father’s toi, there was not enough room in the house for all the guests. We set up the family yurt behind the house, and I and one of Tynara’s other American students lived there. Yurts aren’t private places. There were a lot of children at this gathering, and they spent most of the time in the yurt with us. The door to a yurt is a wool flap that stays rolled up during daylight hours. No one knocks. You don’t have to say anything when entering. One little girl would walk in, take off her shoes, find an empty spot on the floor, and sit down. Sometimes I talked to her, sometimes I studied, sometimes I took a nap. She would leave after about five minutes, not needing to say goodbye. She usually came back five to ten minutes later with one or eight of her cousins in tow.

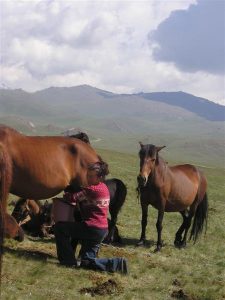

This lack of privacy gave me an opportunity to see people’s everyday lives in Naryn. The family didn’t mind that I watched them while the children did their chores, while they washed the dishes, or while they milked their mares. I have yet to meet a Kyrgyz who doesn’t like kymyz, a drink made from fermented mare’s milk. I had tried kymyz several times by this point—I could hardly avoid it (and it does taste good after the third or fourth time). At Son Köl I got to try kymyz before it becomes kymyz. They milked the mares and simply handed me the bucket. There are no tours that will do that.

Osh: Places Don’t Talk, People Do

The southern city of Osh is built around a large hill called Solomon’s mountain. It’s named after King Solomon, of Qu’ranic (and Biblical) fame. According to tradition, Solomon came to this mountain and prayed. There is a small mosque on the top of the hill, built around five impressions in the rock (supposed to be the imprints of Solomon’s knees, hands, and forehead). The impressions are actually likely the remnants of a Zoroastrian shrine (Zoroastrianism used to be very strong in Kyrgyzstan). A huge museum juts right out of the mountain. I suggest you walk right past it. If you go into the museum, you’ll see some rock-art reproductions, a few interesting Islamic artifacts, and a lot of taxidermy. If you bypass the museum, you can see what makes Solomon’s mountain an important site: the people.

Suggestion #9: You learn more by talking than by looking.

A lot of Kyrgyz told me that people in southern Kyrgyzstan are more religious than people in the north. I don’t know how true that is, but there are certainly more religious sites in the south. There were all kinds of smaller shrine sites on the mountain–caves with supposed spiritual powers (very small and hard to fit into, but the rock is absolutely smooth from centuries of people crawling in), indented rocks that people (of all ages) slid down in order to be healed. There seemed to be as many different perspectives on this as there were people. Many said that the sliding-rock had healing powers. However, one very conservative man I talked to—a Tatar from Novosibirsk, Russia—said that was actually a false belief. He said Allah healed the people if they believe; the rock was just an instrument.

Talking made me wish I hadn’t wasted my time or money on the museum and instead had spent more time with the people. I saw this man accompany his children into the cave and pray with them. Later, at the top of the mountain, he invited me to join his family in prayer. I learned nothing from the museum. I learned everything from the people who came to Solomon’s Mountain, not as tourists, but as believers.

Suggestion #10: Walk (and shop) the bazaar.

Bazaars sell fruit and eggs and laundry detergent and plumbing supplies and meat still hanging on the hook. At the livestock bazaar in Karakol (Issyk Köl province), you get to squeeze through waves of horses, sheep, yaks, cows, and humanity. They sell piglets out of the trunks of their cars.

I especially recommend the bazaar in the center of Osh. In the summer, there are literally mountains of watermelons, sold whole or by the slice. I tasted absolutely fresh figs for the first time in my life. You can hunt for nuts and spices and hear the traders call out to compete for your business (in Kyrgyz, Uzbek, Russian, and sometimes even in English). It might be a little easier, comfortable, or even more sanitary to shop in the Turkish chain-stores in Bishkek but, in my opinion, cashews and raisins taste better when you bargain for the price and then pick them out of the sack yourself.

Jalal-Abad: Be Kind to Strangers.

While traveling through the southern provinces, our car broke down on the way to a mazaar (“holy site”). The car overheated, and our driver went down to a nearby farm to ask for water for the radiator. We could hear talking and laughing, and a few minutes later he came back. We couldn’t see his water canister. When we asked him where it was, he said, “It’s down there. We’re staying here tonight.” We walked to the farmhouse as he drove the car down a small path into the nearby fields. Six men came from the house, greeted us, opened the hood of the car, and began a very animated conversation about what was wrong and who could fix it.

We went to the farm. The family sat us down, fed us (we had to stop them from killing a chicken—we weren’t that hungry), told us where the spring was so we could wash, laid out bedding in the yard next to the donkey and chickens, hung our belongings in a tree, and wished us well when we left the next morning. They didn’t ask our names, didn’t ask where we came from, and didn’t ask for payment. And they fixed our car.

This is normal for rural Kyrgyzstan. Traditionally, you don’t need to knock at a yurt when you approach it. As I walked around the farm yard at sunset, I could see mountains in the distance that looked three distinct shades of blue. I’m not even sure what color the sunset was. All I could hear were a few animals, children completing their chores, and the adults laughing in the house as they finished their day. I think it was one of the more beautiful things I’ve ever seen in my life.

I couldn’t have planned that if I tried.