This resource is intended to serve as a map for the Russian labor market both in terms of official and unofficial labor practices and with general commentary on perspectives of these labor practices as taken from both the employee and employer. We have also tried to provide, wherever possible, commentary on Russian terminology and slang about the workplace. We hope that this will be useful to those interested in doing business in Russia, in working in Russia, and in the day-to-day lives of Russians in general.

For more on the specifics of being hired as a foreigner in Russia, please see our Guide to Work in and Concerning Russia.

Part I: Types of Employment (занятость) in the Russian Federation

- Full Time (полный рабочий день)

Most positions in Russia are full time: 40 hours a week. However, since all salaries are figured monthly (not hourly), the actual number of hours worked is not always an important factor, so long as all job duties are completed (and the number of hours does not go over 40).

- Shortened Full Time (укороченный рабочий день)

Workers under 16, students under 18, the disabled, workers in hazardous conditions, pregnant women, primary caretakers of young children, and others are entitled to shortened workweeks. Often these weeks are not paid the same as full workweeks, although in some instances the worker can collect additional funds from the Russian State Social Insurance Fund (see “Taxes” in Part III of this text).

- Part Time (неполный рабочий день)

If the employee already has a primary job, the hours of their second job are restricted to 20 per week. Sometimes, in special circumstances, an employee will be hired specifically for part-time work (is pregnant, disabled, etc). Salary is still figured monthly.

- Temporary Work (временная робота)

An employee may be hired for a term not to exceed five years to fulfil a special duty such as: a handyman hired to remodel an apartment, a marketing rep hired to work abroad, a creative sphere employee hired to develop a new company logo, etc.

Commentary: Temp agencies are growing in popularity in Russia. Much as in America, companies can lease employees for a definite or indefinite period of time. Companies sometimes prefer this arrangement because it makes hiring a temporary employee for, for example, seasonal work easier and makes “firing” the employee much easier. Since the employee is officially employed by the temp agency, there is no official hiring or firing when bring in or moving out a temp employee. Many companies once hired nearly all their employees, even long-term employees, from temp agencies to take advantage of this. This is becoming less common, however, as state regulations and enforcement have been tightened.

II. Equal Opportunity (Равные возможности)

- Equal Opportunity in Sex and Age (равные возможности по полу и возрасту)

While Russian courts will treat any employee as equal, employers can establish almost any criteria they wish for positions. For example, it is very common to see ads for secretarial positions advertising specifically for a “woman, age 18-24” or for a construction worker advertising for a “man, age 18-34,” etc. Women are, in fact, still legally barred from some professions under a Soviet-era law and an assumption that the jobs (such as ship captain) are too physically taxing for women.

Commentary: Although Russia may seem behind the times when it comes to women in the workplace, polls have shown that Russians are, in fact, some of Europe’s most open-minded when it comes to thinking that women can perform just as well as men in the workplace. Russia also ranks first in Europe for the number of women in upper management positions.

- Equal Opportunity in Race and Nationality (равные возможности по национальным признакам и расовой принадлежности)

It is legally forbidden to discriminate on the basis of race and nationality in Russia, a country that contains hundreds of such differentiations and a great number of large cities. One never sees job advertisements for “Russians only.” However, informally this type of discrimination is still fairly commonly practiced.

Commentary: The phrase “Равные возможности” worked its way into the Russian language around 1990, as the economy was being revamped along western lines and hence the phrase’s close similarity to the English. Below are a handful of other phrases using the phrase and concept:

- наниматель, предоставляющий равные возможности (Equal Opportunity Employer)

- равные возможности между лицами разного пола

- равные возможности между мужчиной и женщиной

- равные возможности в труде

One may also use the word “Равенство:” (Equalty)

- равенство в труде

- равенство на работе

- равенство при трудоустройстве

III. Looking for a job? (Ищете новую работу?)

Where to look for a job (где искать работу)

Where to look for a job (где искать работу)

Most Russians now use websites to search for professional job placements. Professional placement “headhunting” agencies are also commonly used by both employers and job seekers. The most effective means to find a job, of course, is through personal contacts. In Russian there are phrases for this including: “пошарить по своим каналам,” “пошарить по своим знакомым,” “пошарить по старым каналам,” and “продавить по своим каналам.” All of these phrases mean “to pull strings.” For specific websites, placement agencies, and more on finding on a job in Russia. See our Guide to Working in Russia.

- How to apply for a job (как подавать заявление о приеме на работу)

- The application (форма заявления)

Applications are not particularly common in Russia, save for in some international companies. Often, when an application is used, it is “short and sweet,” not the monsters one often encounters in America. We have included here an example application from McDonald’s (as a zipped pdf file).

- The resume (резюме)

The resume is considered the primary document with which one applies for a job. They look much like they do in English, although often a photo is included, as one is usually kept with employee records anyway. For an example of a resume in Russian, click here.

C. The job interview (собеседование при приеме на работу)

The interview usually begins with a short telephone interview (собеседование по телефону), to determine the candidate’s basic qualifications including, for example, availability for the job/workday, education, past work history, friendliness, and any specific that job might require such as certifications and/or knowledge of a foreign language. This interview is often conducted by the human resources manager.

If the telephone interview goes well, the candidate is called in for a face-to-face interview (личное собеседование). This interview is often conducted with several people, including the company director, the head of the department and sometimes even a company psychologist. Part of this interview may be conducted in a foreign language, if that is a requirement for the job. English is the most important foreign language in Russia but depending on the nationality of the company or clientele, German, Chinese, Swedish, etc. may also be the make-or-break issue to getting hired.

IV. Getting Hired (найм на работу)

- The Job Contract (трудовой договор; контракт)

ALL employment in Russia must be by contract. Employment by verbal agreement only, common in America, is illegal in Russia. The contract must stipulate what the employee’s job description and compensation will be. Generally, the job description is very broadly defined, since an employer may not ask an employee to perform a duty not defined in the job contract without providing extra compensation. This job contract may stipulate any requirement or condition, but may not impinge upon a worker’s rights as set forth by the Labor Code of the Russian Federation (Трудовой Кодекс Российской Федерации).

- Documentation (документация)

- Passport (паспорт)

A copy of the employee’s passport is made for company records. National passports are the major means of ID in Russia and must be carried by all persons over the age of 14. Russian police may stop any person at any time without cause and if that person does not have proper identification, they can be subject to fines and detention. Separate international passports are used for foreign travel.

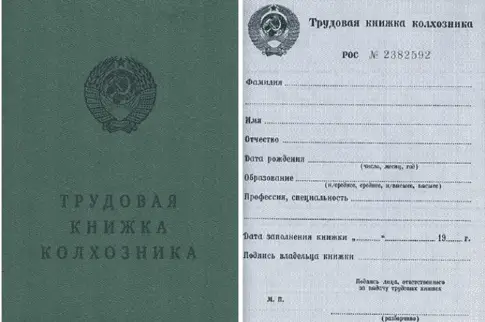

- The “Work Book” (трудовая книжка)

Roughly equivalent to the American Social Security Card, this passport-sized document provides proof of where, when, and how long an employee worked in a given position and location. No remark is made to the exact duties performed or performance quality. The work book is required to claim retirement funds from the state. The employer must keep the book for the duration of employment and return it, updated, signed, and stamped, on the last day of employment.

- Photographs (фотографии)

A work book from the USSR (collective farm edition)

Most employers will also collect several passport-sized photographs of their employees. These are standard in company records and are often needed to make a special pass (пропуск) for the employee. Russia is awash with security guards, a holdover from the Soviet era, and most employees must show a пропуск as special identification to access their work places.

- D. Other information (другая информация)

Employers have the right to collect other personal identification as required by company policy and/or the law, with certain restrictions (information about religious and political beliefs, for example, is forbidden).

- The “Work Order” (приказ о назначении на должность)

By Russian law, the employer must issue an executive order saying that the employee has been hired no less than three days after the contract takes effect. This order must be counter-signed by the employee. Similar orders (приказы) document any change in the employee’s status with the company (raises, vacations, promotions, disciplinary actions, etc.)

– After these steps, the employee is legally hired.

For more on the specifics of being hired as a foreigner in Russia, please see our Guide to Work in and Concerning Russia.

V. Probation Period (Испытателчый срок)

The job contract may stipulate a probationary period for up to three months. During this time, the employee may be terminated with only three days written notice (приказ об увольнении). The notice must state the reasons for dismissal and those reasons must be among those grounds for dismissal already approved in the labor code or job contract. During this time an employee may quit with three days’ notice without giving reason.

- Probation For Managers (Испытательный срок для руководителей)

Employees hired for top-level management positions may be subjected to a six-month probation period so as better judge the employee’s work performance and moral.

- Probationary pay (Зарплата на испытательный срок)

Pay during the probationary period is generally less, sometimes by as much as half.

Commentary: While the practice is illegal, it sometimes happens that employers will keep probationary employees on staff and simply release them at the end of the probationary period for not meeting standards. This allows employers to save on salaries and, since many workers do not know their rights or how to have their rights enforced, the system is relatively safe.

Commentary: It is not at all uncommon (although illegal) for workers to agree to a one month probationary period without a contract. Payment for this period is made under the table. Employees sometimes prefer this as they do not want a one- or two-week employment period to appear in their work books as they fear this questionable blemish may hinder their ability to find future employment.

VI. Working (рабочий день)

- Regular Work Hours (нормативный рабочий день)

Unless their contract states otherwise, most employees may be required to work up to 40 hours a week for the standard pay stipulated in the job contract.

- Overtime (работать сверхурочно; оплата за сверхурочную работу)

Overtime is possible only with the employee’s written consent. The first two hours of overtime require time-and-half pay (полуторной оплаты трудочаса). Double-time (двойная зарплата; двойной оплаты труда) must be paid thereafter.

- Holiday Pay (плата за работу в выходной день)

There are 12 official holidays in the Russian Federation. Time worked on these holidays must be paid double (in most instances). The employee’s willingness to work those must be confirmed in writing.

- “Moonlighting” (“халтурить” – slang)

In Russia, earning extra money by doing extra jobs or work is an incredibly common practice and entails an incredibly rich volume of jargon and slang.

- “Work on the side” (работа по совместительству – standard Russian)

When an employee performs tasks or works hours outside of those indicated in their contracts as a temporary event, this should be legally documented by an executive order from management (like that issued when the employee was hired). The money earned from such an arrangement is referred to in Russian slang as “шабашка,” a word related to “башлать” (this word in not commonly used – again, just replace with something that makes sense – something that give more information about related Russian words – or, simply delete.), which is slang for “to pay.” The act of working on the side is also often referred to with the phrase: “совмещать две специальности” more specific cases can be referred to with the following example construction: “программист и по совместительству переводчик” (where the employee is primarily a programmer, but has been asked to perform translations). While this is a fairly common legal construct in Russia, it is foreign to American thought. Where most employment is done via verbal agreement, most employees can be asked to do nearly anything the company needs or wants.

- Working a second job (подработать; подработатьна стороне – standard Russian)

Earlier, while it was of course possible to work two official jobs, secondary employment for most Russians was kept under the table. This arrangement once provided an incredible number of taxi drivers (who drove unmarked cabs), but has since abated considerably with improved regulation of the market. In recent years, some advances were made – an official entry about a sideline job can be made in a workbook which is kept at the first job. There are still many Russians, though, who work as tutors and handymen, for instance, for under-the-table extra cash.

VII. Compensation (компенсация)

- Forms of Compensation (Формы возмещения понесенных расходов; Виды компенсации)

As a rule, Russia does not use checks, personal or business. All employees are required to have a bank account to accept direct deposit payments (прямое зачисление в депозит по платежной ведомости). To facilitate this, employers will often open an account for the employee at the same bank the employer uses for company funds. This is often done even when the employee has another account at a different bank already. A small and federally regulated part of an employee’s salary may be paid in kind (таким же образом; подобным образом). This sometimes includes cell phone usage, food, housing, or transportation.

- Minimum Wage (минимальный размер оплаты труда)

Minimum wage is set at a low 11,163 RU per month in 2018 (US $168.6). However, virtually nobody pays minimum wage. An unofficial standard minimum for undocumented (illegal) blue-collar employees seems to be around 800-900 RU per day in Moscow. The Moscow government has established an official “living wage” (прожиточный минимум) for Moscow at 15,800 RU per month for the 1st quarter of 2018.

Commentary: Like the minimum wage, most agree that the living wage is also set below what is actually needed to eat healthily, pay rent, and purchase other necessities.

- Unofficial and Official Income (Легальные и нелегальные доходы)

To save on taxes, many companies will insert one figure into the work contract but have verbal, unofficial agreements with their employees for a higher sum (sometimes 50-100% more). This arrangement is illegal, but common and can only be enforced on an honor system. In slang, these incomes are referred to as “Белый доход и черный доход.” Although the situation has improved greatly since the 90s, today 25% of all Russians receive all or some part of their income “under the table.”

- Average Income (средний доход)

Officially, as of July, 2018, the average official wage for all of Russia was 42,413 RU per month gross (640 US), with 36,900 net amount after income tax deduction. The average unofficial wage has been quoted, however, at lower amounts, including such as 18,000 RU. Moscow is estimated to now have an average income of 80,999 RU (1223,08 USD). There is a big spread in incomes across the regions of Russia, with the highest average income in Moscow – 80,999 RU and St. Petersburg – 59,604 RU, high incomes in Kamchatka, Magadan, Sakhalin, and Chukotka – 65,000 – 98,000 RU, and the lowest average incomes in the southern regions, the Volga area and North Caucasus, with averages coming in at 26,000 – 32,000 RU.

- Currency and Timing Restrictions(валютные и временные ограничения)

All salaries earned in Russia must be paid in rubles and paid in twice-a-month installments. These installments are not always equal. Because many businesses charge for their services by the month, this is not always a convenient arrangement for the employer. To compensate for this, some employers will pay a small sum (called an “аванс“) in the middle of the month and a larger sum (referred to as simply “зарплата“) at the end.

Commentary: In many contracts, salary was once stated in dollars or euros and a conversion applied each pay period using the current exchange rate (курс). There is no binding law for requiring all salaries to be listed in rubles, but Russia’s Federal Employment Service has been strongly advising salaries to be listed in rubles for some time. To avoid conflicts with the authorities, for some high-value employees, companies changed the contracts, but then signed an additional agreement allowing for the sum to be adjusted based on exchange rates. Thus, the paperwork was reversed but the situation stayed largely the same. Paying salaries in “hard currency” helps protect employees from inflation (which is still about four times greater in Russia than it is the US) and, for foreign employees, can be essential to maintaining the viability of the employment (as foreigners often have expenses in their own currencies. It can place businesses at risk, however, if the value of the ruble suddenly goes down compared to the foreign currency. This is especially true if most of the business’s income is earned locally in rubles, rather than from international companies paying in dollars or euros. All this is perfectly legal, so long as the actual salary is paid in rubles.

VIII. Taxes (налогы)

- Personal Income Tax (Налог на доходы физических лиц – НДФЛ)

Russians pay a flat rate on their salaries of 13%. Individuals who work in Russia but who do not live there for more than 180 days per year (referred to in the tax code as “нерезиденты” or “non-residents”) pay 30% tax.

- Unified Social Tax (Единый социальный налог – ЕСН)

The Unified Social Tax is a regressive tax paid by employers on salaries (actually it was cancelled in 2010, but there are still some taxes which can be referred to as the Unified Social Tax — please change to use the official new terms). It ranges from 30-15% but the regression away from 30% only begins for monthly salaries of 300,000 rubles, which is more than most Russians could ever dream of receiving, meaning that 30% is the rate applied to nearly all salaries. The tax consists of three: contributions to the Pension Fund, to the Social Insurance Fund and to the Mandatory Medical Insurance Fund. Most social programs are funded by this tax and among them, the Russian State Social Insurance Fund (Фонд социального страхования Российской Федерации), roughly similar to America’s Social Security Program.

Commentary: Avoiding the Unified Social Tax, which is fairly high, is probably the main reason that some employers do not document their employees. This situation has improved since Russia lowered the tax and simplified its structure, but the situation is still problematic.

For more on the specifics of being hired as a foreigner in Russia, please see our Guide to Work in and Concerning Russia.

IX. Vacation and Leave (отпуск)

- Paid Vacation (оплачиваемый отпуск) (100% of regular pay)

All Russian employees are entitled to 28 paid vacation days per year (in addition to the public holidays already discussed). These days must be requested in advance and approved by the employer by an official order. They need not be taken consecutively. If an employee holds two jobs, the secondary job must grant paid vacation time concurrent with that granted by the primary job. The pay an employee receives for this vacation is referred to as “отпускные” and is the employer’s responsibility to pay.

- Sick leave (отпуск по болезни, больничный)(60-100% of regular pay)

Sick leave is paid by the Russian State Social Insurance Fund. Employees are required to bring proof of illness (a note from the doctor) to their employers, but only after they are well enough to return to work. An employee is not required to inform their employer that they require sick leave until this time. An employee may not be fired during sick leave.

- Maternity Leave (декретный отпуск, отпуск по беременности и родам)(60-100% of

Mother and child regular pay)

Maternity leave is paid as a percentage of regular wages by the Russian State Social Insurance Fund. Maternity leave begins 70 days before the due date and extends to 70 days after the delivery date but can be extended in the event of complications with the pregnancy.

- Child-care leave (отпуск по уходу за ребёнком) (Sometimes paid)

A new mother or primary caregiver may request partially paid child-care leave (it is paid until the child is one year and a half). This is paid by the state (as above) but must be honored by the employer. A mother has the right to unpaid leave and to reclaim her job until her child is three years old. Fathers can take such a leave as well if the mother does not, but in reality, such cases are extremely rare in Russia. To claim child-care leave, documentation must be supplied by the other parent’s place of employment confirming that that parent is not claiming the leave.

Commentary: If a woman has a second child during the three years of leave she is entitled to, she is entitled to renew the leave for the second child. Leave related to child-bearing is obviously not an advantageous arrangement for the employer, as it can make a female a near permanent and non-present employee.

X. Disciplinary action (дисциплинарное взыскание)

Disciplinary action may occur only under set circumstances strictly defined in the Labor Code (such as drunkenness on the job, failure to complete duties, etc.) and must be documented by an order signed by a council of at least three employees. The employer may apply following disciplinary actions: oral or written rebuke, issue a reprimand, fire an employee (устное или письменное замечание, объявить выговор, уволить работника)

XI. To Fire and to Quit (увольнять; уволиться с работы)

- Quitting (Увольнение по собственному желанию)

Quitting employees must give two weeks written notice.

- Firing (Увольнение по инициативе работодателя)

To fire an employee for misconduct or poor work performance, the employer must provide proof of disciplinary action (sometimes proof of several instances, depending on the infraction – see above). There are still greater restrictions on firing certain groups such as minors and union members; women in particular are almost impossible to fire under legal auspices. Plus, in order to officially fire an employee, the employee must be given advance notice in writing and the final termination must be documented and co-signed by the employee.

- Severence (Выходное пособие)

An employee who is fired job is entitled to receive a severance payment from the employer equal to two months’ wages, according to Russian law.

Commentary: The labor code is generally weighted in favor of the employee in this instance and employers who wish to operate “by the book” often complain that it is almost impossible to fire an employee once hired.

XII. Unemployment (безработица)

- How to Apply for Unemployment (Как оформлять получение пособия по безработице)

If the employee had worked 26 fulltime weeks before being discharged on honorable grounds or quitting “with good reason,” he/she may register with their local Employment Service (биржа труда) and apply for unemployment benefits (пособие по безработице). For the first three months of unemployment, the unemployed receive 75% of their former wages, then 60% for another four, and 45% for another five months. For an additional year, if the applicant does not find a job within 18 months, the unemployed may receive benefits in the sum of the official minimum wage multiplied by the regional factor (районный коэффициент), such as 15 percent in the Ural region or 100 percent in the Far North of Russia. The minimum amount of unemployment benefits is 890 RU, the maximum amount – 4,900 RU. In Moscow, 850 rubles are added to the amount, that is, the minimum unemployment benefit in Moscow is 1,700 RU.

- Funding and Administration (финансирование и администрация)

The Ministry of Health Services and Social Development (Министерство здравоохранения и социального развития) provides general supervision, control, and partial financing for the program. Regional employment services are charged with administering and financing the program.

Commentary: 5.2 percent of working-age Russians were officially unemployed as of 2018. However, only about 1% of working-age Russians had registered with the unemployment office and were receiving benefits. Low registration is due, in part, to the fact that benefits are very low, particularly for those who have been unemployed for more than a year. Also, benefits are calculated by the employee’s official wages, which may be much lower than an employee’s actual wages. (See section III).

Commentary: The official minimum subsistence level varies across Russia. In Moscow, it is calculated at 16,463 RU per month and in Irkutsk, at 10,452 RU per month. In Moscow, a forty-five percent payment would thus be equal about $112 US.

XIII. Retirement (отставка; выход на пенсии)

Standard retirement age in Russia is 65 for men and 60 for women (from January, 1 2019). Those who have worked in certain dangerous conditions can retire early and teachers, nurses and doctors may retire after a set number of years (25-30). Retirement age for government workers is six months longer than the standard.

- State Pension (Пенсионный Фонд Российской Федерации – ПФР)

Russia’s state pension consists of two parts. The first part is calculated depending on one’s work experience (not less than 9 years) and the total amount of the contributions to the Pension Fund (see section VII). The second part is not obligatory and depends whether or not a person applied for it. It is calculated based on the personal savings in the Pension Fund (and the size of the first part will be decreased). Actually, the system is quite complicated and Russians themselves do not fully understand how it works. If a worker chooses to remain in the labor, he/she can’t receive a pension and earns a bonus multiplier, which leads to the increase of their future pension. Theoretically, pensions are to be indexed for inflation each year, although the government in crises years has withheld this index and crises years have, unfortunately, not been few. The average pension is currently 14,100 RU (212 US) which is about 30 percent of the average salary.

Commentary: Again, the presence of official and unofficial pay poses a problem, because the pension is figured based on official pay. (See section III)

Commentary: One thing that President Putin is credited with is reform of the pension system. Most pensioners who own their apartments now claim that they have enough to feed and clothe themselves (which is a major improvement from the nineties). Medications are still a heavy burden.

- Private Pension Funds (негосударственные пенсионныефонды)

A handful of large, highly successful companies have retirement programs for their workers, but these are very rare. There are some private investment firms that are now helping private individuals create personal retirement funds. The Russian state is also trying to attract more funds from individual retirement investments and has launched several programs to do so. Such programs have not generally be successful. One such program was a pension co-funding scheme – until 2014, the state would match voluntary donations of 2,000 to 12,000 RU to state pension accounts.