What shapes Kyrgyz national identity? The answer is complex and personal, but one key element is the Kyrgyz national narrative. This includes the heroes and pivotal events taught in schools, the places central to the nation’s collective memory, and the language and beliefs that frame its worldview.

A national narrative goes beyond history: it is the people, events, places, and values that define how a nation understands itself. It lives in literature, film, and art, in monuments and place names, and in the calls to action used by leaders and activists.

This resource presents Kyrgyzstan’s national narrative in a concise, accessible way to help outsiders—tourists, students, and diplomats—grasp the cultural foundations of Kyrgyz society and better understand the Kyrgyz nation.

Special Themes in Kyrgyz Identity

Kyrgyzstan is 74% Kyrgyz. More than 95% of ethnic Kyrgyz in Kyrgyzstan identify as Muslim. Various estimates place the country’s overall Muslim population at between 80-90%.

The Kyrgyz language has a complex relationship with Kyrgyz identity. Kyrgyz who live outside major cities often speak only Kyrgyz and consider it an essential marker. However, many Kyrgyz in large cities speak mostly Russian and can be embarrassed when asked to speak Kyrgyz, which they may know only haltingly. Most Kyrgyz would agree in principle that a Kyrygz person should be able to speak Kyrgyz, yet this is not always true in practice thanks to the legacy of the Soviet Union.

Religion is also complex in Kyrgyz identity. While the vast majority of Kyrgyz identify with Sunni Islam, and while the country is home to numerous new and beautiful mosques, religious observance is relatively lax. Alcohol and non-halal food are widely available and beards are not common (although hijabs are increasingly so). Further, many Kyrgyz, especially young, educated, and nationalist Kyrgyz, believe that Kyrgyzstan’s pre-Islamic Tengrist heritage is a truer expression of Kyrgyz identity – even if they also practice Islam. In fact, Islam in Kyrgyzstan is heavily influenced by the Tengrist heritage that preceded it, giving it a particularly local flavor. Holidays, whether state or religious, are celebrated largely with Kyrgyzstan’s traditional pre-Islamic dress, cuisine, and practices.

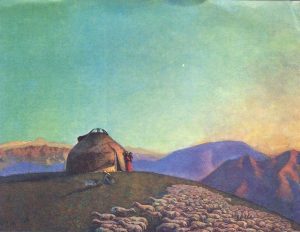

Nomadic heritage is the source of many Kyrgyz traditions and symbols. Falconry, animal husbandry, and equestrian sports, once central to obtaining food and defending their homeland, are today still practiced as treasured traditions (such as exhibited in the World Nomad Games). Kyrgyz national cuisine, reflecting a heritage based in nomadic pastoralism, is heavy on dairy, fats, and meats like mutton and horse. Kyrgyzstan’s population is 65% rural and a small percentage of Kyrgyz are still nomadic, migrating as their ancestors did between the high pasture lands in the summer and the valleys in the winter to care for livestock.

Yurts served as traditional Kyrgyz nomadic housing for centuries. Today, they are strong symbols of both family and the state. They are used by the tourism industry to create what are marketed as unique, local experiences. The centerpiece of the yurt, the tunduk, which holds the collapsible felt structure together, even features on the Kyrgyz flag.

Tribal identity lives within and alongside Kyrgyz identity. The Kyrgyz, according to legend, were formed when the legendary hero Manas united 40 tribes. These tribal affiliations still exist and continue to play both social and political roles. The tribes are both a source of unity within Kyrgyz culture and sometimes a source of rivalry, especially between those indigenous to the south (which is more rural and Turkic-influenced) and the north (which is more urban and Russian/European influenced).

Family, ancestry, and elders are to be shown absolute respect in Kyrgyz culture.

The kalpak is a tall men’s felt hat, most often black and white and sometimes featuring gold embroidery. Part of Kyrgyz traditional dress for centuries, it fell out of fashion under Soviet rule. Symbolizing important parts of Kyrgyz identity, it is making a massive comeback today. Its four sides represent the four elements and four cardinal directions central to the Tengrist nature-focused belief system. The florid embroidery represents a family tree with the tassels on top paying homage to ancestors. Any celebration today features a sea of kalpaks. They are sometimes worn as everyday dress and reflect pride in being Kyrgyz.

Manaschi are reciters of Manas, the national epic that describes the legendary origin of the Kyrgyz people. Often trained from very young ages, manaschi know thousands of lines of the poem and compete in national events. They are highly regarded for their dedication to Krygyz culture and for carrying on an ancient national tradition.

The komuz is a three-stringed instrument whose shape resembles a horse head, and many of the songs played on it evoke the rhythm of riding a horse. The instrument often accompanies a manaschi’s song and is played as an opening to many national events.

Geography in Kyrgyz Culture

Kyrgyzstan’s nature occupies a central place in the national imagination, particularly as it relates to its Tengrist heritage. Tengrism, the pre-Islamic, nomadic belief system, holds that a common life force pervades all things and that many natural formations such as waterfalls, high mountains, and the sky are sacred.

Mountains, namely the Tian Shan and Pamir mountain ranges, cover 94% of Kyrgyzstan. This has influenced the country’s cultural development in numerous ways, particularly in that intensive, wide-scale agriculture is difficult, meaning that the Kyrgyz have relied on pastoral nomadism for the production of food. This, in turn, means that their diet is meat- and dairy-heavy, that equestrian skills are valued, and that the yurt, a form of transportable housing, is the national symbol of home.

A north-south divide has been created in Kyrgyzstan because its mountain ranges run east-west. This effectively creates a series of walls between the two sides, hindering transport and communication between them. That these two sides took slightly different historical and cultural development paths is not surprising. The north is more influenced by Russian and European traditions and language and the south is more Turkic. The division has also created a cultural and political rivalry that persists to this day.

Issyk Kul is a giant saltwater lake that covers most of what is not covered by mountains in Kyrgyzstan. Its name translates to “warm lake” because its salt content prevents it from freezing in the area’s very cold winters. The word “Issyk” also derives from an older Turkic word meaning “holy;” Issyk Kul is considered sacred to Tengrists and many legends surround it. The most famous tells of a girl so distraught in her desire to resist the khan’s advances that she formed the salty lake with her tears. Today the lake is associated with summer vacations for both locals and foreigners arriving to its shores for hiking, swimming, horseback riding, and relaxing on the beach at one of the many resorts or yurt camps.

Biodiverse nature abounds in the tiny country of Kyrgyzstan. This is driven by microclimates created by the mountains that rise to an astonishing 4.5 miles above sea level and sink rapidly to valleys as low as just one mile above sea level. It is also fed by the glaciers that cover about 30% of the country, formed at the high peaks and making Kyrgyzstan Central Asia’s most water-rich country, with a plethora of fast-moving, small water sources. This means the Kyrgyz are used to moving between mountain forests, alpine lakes, valley plains, and hard-packed red deserts, often within a few miles of each other.

Bishkek, with 1.1 million people, is Kyrgyzstan’s largest city and its political, economic, and cultural capital. Founded in 1868 as a Russian outpost in northern Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek is dominated by Soviet architecture and home to most of Kyrgyzstan’s largest businesses. Most Kyrgyz hoping to move up the socio-economic ladder dream of either moving to Bishkek or moving abroad to a still larger, usually Western city.

Osh is Kyrgyzstan’s oldest city, dating from around the 5th century BC. An early Silk Road outpost, Osh is still known as a city of commerce with large bazaars and a lively trade of Chinese goods being bought and sold further abroad. With 350,00 inhabitants, it is Kyrgyzstan’s second largest city and often functions as a rival power center in Kyrygz politics. Located on the Uzbek border in Kyrgyzstan’s south, Osh is home to a strong concentration of Kyrgyzstan’s Uzbek minority. The culture and even the Kygyz language spoken here shows much stronger Turkic influences than the more Russian-influenced Bishek.

Kyrgyz Historical Heroes

The following people have played pivotal roles in Kyrgyzstan’s history and can be thought of as “founding fathers.” You may see monuments to them and places named for them.

Barsbek Kagan ruled the Yenisei Kyrgyz at the turn of the 8th century. Considered by some as the first great Kyrgyz leader who sought an independent Kyrgyz nation, he had to contend with the Mongols, Chinese, and Turkic Khanate to maintain his state. He eventually died in battle and the Yenisei spent most of their history as vassals or subjects of more powerful states. Barsbek has been honored with a statue in Osh, streets named in his honor in several cities, and a commemorative coin. His name, associated with greatness, is still a common given name among Kygyz.

Manas is a legendary historical figure who united the forty tribes of Kyrgyzstan into a single nation sometime around the 10th century. His story, recorded in The Epic of Manas, is a thousand-year-old epic poem nearly a half million lines long. Manaschi, performers who can recite the poem from memory for hours on end, have passed it down for countless generations. First written down in the 18th century, the epic is taught in Kyrgyz schools as a literary masterpiece, a loose historical text, and an important source of moral lessons and recorded traditions.

Kurmanjan Datka initially helped lead the resistance to Russia’s invasion, and later negotiated surrender when it became clear that the Kyrgyz faced inevitable defeat. For both actions, she is regarded as a hero who helped preserve Kyrgyz culture and save Kyrgyz lives. Not a traditional female for her time, she fled an arranged marriage and instead married a man of her choosing, Asylbek Datka, the leader of the southern Kyrgyz tribes. She gained respect and eventually took over after her husband’s death, taking the title of “datka,” or “general.” She is honored on the Kyrgyz 50 som banknote, by many statues throughout the country, and was recently the subject of a major state-financed biopic.

Kasym Tynystanov was a Kyrgyz linguist and author in the early twentieth century. He initially worked to reform the Arabic-based Kyrgyz alphabet and later oversaw the transition to a Latin-based script in 1928, (the Cyrillic alphabet was later adopted in 1940). He wrote the first Kyrgyz grammar textbooks as well as original plays and poems in Kyrgyz and translations into Kyrgyz. Killed in Stalin’s Great Purge of 1938, he remains a national hero for his efforts to promote Kyrgyz literacy and as a founder of Kyrgyz written literature.

Semyon Chuikov is considered the father of modern Kyrgyz painting. Born in 1902 to an extremely poor family, Chuikov spent much of his time outdoors exploring and sketching natural landscapes and people before being tapped to study art in Moscow. Known for his purposeful use of light to illuminate humble people against vivid landscapes, he was awarded a prestigious Stalin Prize in addition to high honors at international exhibitions such as the 1958 Brussels World Fair.

Chingiz Aitmatov wrote novels about life in Kyrgyzstan starting in the 1950s. The most decorated Soviet writer ever, he has been translated into over 100 languages and is known for showing the Kyrgyz experience to the rest of the USSR and the world. In politics, he served as advisor to President Gorbachev, as a Soviet and then Kyrgyz ambassador to European countries, and as a member of the Kyrgyz Parliament. Today, he is celebrated as a writer who navigated Soviet censorship while pushing for greater rights for Kyrgyzstan and respect for Kyrgyz culture. Today, his former home is a museum dedicated to his life and works.

Other Names of Note

Roza Otunbaeva was the first and only female president among the five Central Asian republics. After serving as an interim acting president, she was also the only national leader in Kyrgyzstan’s history to hand over power peacefully and democratically.

Iskhak Razzakov is best known for attracting Soviet investment to the Kyrgyz SSR, overseeing the construction of factories, roads, schools, and the Orto Tokoy Reservoir. He was also a strong force in establishing Kyrgyz State University.

Baatyr Kaba Uula Kozhomkol is a historical figure glorified for his extreme strength. Legend has it that he stood over 7 feet tall and was strong enough to carry his horse. This feat has been captured in a statue outside the Kozhomkol Sports Palace in Bishkek.

Historical Events

These historical events were pivotal in the formation of the Kyrgyz national narrative. They are parts of the Kyrgyz story that are taught to school children and considered fundamental components of the Kyrgyz shared memory. For a full history of Kyrgyzstan, see the article at our sister site, Geohistory.

The Kyrgyz Khaganate is considered the first Kyrgyz state. Founded by the Yenisei Kyrgyz, a Turkic-speaking group from the Yenisei River Valley in Siberia, they entered a golden age after being united as a people and defeating the Uyghur Khaganate under the leadership of hero Manas. Altogether, the Khanate lasted some seven centuries, although its size, borders, and degree of sovereignty changed many times. The Khaganate developed a written language, and at various times stretched into modern-day China, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and Siberia. The Yenisei Kyrgyz are only loosely genetically related to the modern Kyrgyz in Kyrgyzstan. Culturally and politically, however, they are considered foundational to modern Kyrgyz identity.

The Introduction of Islam occurred slowly. Starting in the 8th century, the Kyrgyz were initially introduced to it via contact with Arab, Persian, and Turkic merchants, missionaries, and armies whose movement was mostly related to the Silk Road. Under the Kara-Khanids, a confederation of Turkic tribes that became a regional power in the 10th century, a version of Islam specifically adapted to nomadic life was developed and its adoption encouraged. By the 16th century, Islam was a dominant force in the south, but was only adopted among many northern tribes in the 18th century after their conquest by the Kokand Khanate. This very slow and patchy adoption was central to the religion becoming fully intertwined with existing local traditions, giving it a very local expression. Islam is today the professed religion of 95% of Kyrgyz.

Russian Rule was established in the late 19th century and lasted until the Soviet collapse in 1991. Initially, the Kyrgyz were grouped into Russian Turkestan, part of the Russian Empire. Most Kyrygz still see their surrender, as negotiated by the Kyrgyz hero Kurmanjan Datka, as a practical move that avoided bloodshed by accepting the far weaker position the Kyrgyz were in. After the 1917 Revolution, the Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic was eventually created, establishing the modern borders of Kyrgyzstan. The Soviets forced most Kyrgyz to settle, destroying nomadic lifestyles. Kyrgyz intellectuals and dissenters were arrested and/or killed, especially in the Stalinist purges of the 1930s. However, the Soviets also raised the literacy rate among Kyrgyz from single digits to above 95%, more than doubled life expectancy, and grew the economy. Kyrgyz artists and intellectuals, like actress Sabira Kumushaliyeva and writer Chinghiz Aitmatov, renegotiated traditional culture in the contemporary context of “modernism”, “socialism”, and “internationalism,” becoming national heroes in the process. Russian and Soviet heritage is today viewed as having provided benefits, albeit at considerable cost to Kyrgyz culture, lives, and sovereignty. Most Kyrgyz are still bilingual in Russian and Kyrgyz, especially in urban centers.

Urkun (Үркүн), or The Central Asian Revolt of 1916, was a Kyrgyz national tragedy. Starting as protests against land policies that favored Russian settlers, they intensified when a WWI draft of Kyrgyz men was announced and were met with extreme violence by the Tsarist state, which tried to expel the Kyrgyz from Turkestan. Driven from their homes by both verbal threats and rifle attacks, hundreds of thousands fled to China over rough mountain terrain. Tens of thousands of people perished on the frigid journey. Some survivors and their descendants remain in China to this day. Declared a genocide by a Kyrgyz public commission, many Kygyz have relatives in living memory that suffered. However, the only major commemorations of Urkun are a statue at the remote Ata-Beyit memorial site and a movie that struggled to be released. This is generally attributed to Kyrgyzstan not wanting to anger Russia, in part due to Kyrgyzstan’s dependence on remittances from Kyrgyz nationals working in Russia. “Urkun” comes from an old Turkic word meaning “to flee.”

Basmachi refers to the various rebellions against Soviet power in Turkestan. Although some Kyrgyz saw the Bolsheviks as saviors who overthrew an oppressive tsar, many soon chafed at oppression under the Soviets, whose policies disrupted nomadic lifestyles, suppressed Islamic practices, sought to collectivize agriculture, and imposed new political structures. Basmachi rebels fought against this. However, the sporadic, relatively small-scale rebellions did not succeed in seriously threatening Soviet power in the region. The movement is remembered today with a mix of reverence and ambivalence. On one hand, it is seen as a heroic effort to defend Kyrgyz culture and sovereignty against external domination. On the other hand, Soviet historiography painted the Basmachi as bandits and reactionaries, and these narratives influenced perceptions of the movement.

Independence was gained on August 31, 1991. Askar Akayev, a former member of the USSR Congress of People’s Deputies, was declared the first President of the Kyrgyz Republic. He oversaw the transition to a market economy, privatization, new international political and economic partnerships, and a reclamation of Kyrgyz national identity. The capital city Frunze (named after Russian general Mikhail Frunze) was renamed Bishkek and Kyrgyz was enshrined as the state language in the Constitution (Russian continues to hold official status). A renewed interest in religion (especially Islam) sprouted as Soviet pillars of identity dissolved and foreign investment from countries like Turkey surged.

The 2005, 2010, and 2020 Revolutions together have deposed more Kyrgyz heads of state than have elections since independence. Each revolution was driven by allegations of corruption and economic mismanagement. The rapid development and relatively frequent deployment of these revolutions can be seen as indicative of a sense of active collectivism strongly developed in nomadic tradition. Loyalties are expressed not only in words, but deeds. The rapid mobilization this collectivism can support can be seen, for instance, in the historical ability to quickly gather family over great distances to observe traditional funeral practices. Traditional governance also sometimes required a rapid gathering of tribal leaders to make decisions – especially in cases where a common enemy would need to be faced. Stories of quickly gathered forces can be seen in the histories of many Central Asian figures like Manas, Tamerlane, the Basmachi, and Genghis Khan.

Diversity in Kyrgyzstan

Of course, not everyone in Kyrgyzstan is Kyrgyz. The stories and experiences of a country’s ethnic minorities are also part of the lived experience that defines it as a state.

Uzbeks are Kyrgyzstan’s largest ethnic minority at 15% of the population. Uzbeks are concentrated in the south of the country, especially along the Uzbek-Kyrgyz border. They are considered indigenous, having lived in the area for centuries. Almost half of the residents of Kyrgyzstan’s second-largest city, Osh, are Uzbek, and many people there speak a dialect of Kyrgyz that is heavily influenced by Uzbek grammar and vocabulary. Uzbeks and Kyrgyz have often been rivalrous. While in recent years relations have been mostly calm, they have flared into violence at times.

Russians are the second largest ethnic minority at about 3.5% of the population. Most arrived as, or are descended from, Soviet workers sent to help build factories, schools, hospitals, farms, and other infrastructure. This population has fallen since 1991, with many migrating back to Russia. However, Russia’s 2022 war mobilization sparked a new sharp influx of about 65,000 mostly young, educated, urban Russians, which added about 1% to Kyrgyzstan’s population almost overnight. They have typically moved into jobs in IT, arts, and media in Bishkek. The Kyrgyz government responded by launching a “digital nomad status,” which removes some of the bureaucratic barriers immigrants typically face, such as registering a place of residency and obtaining a work permit. This is technically available to anyone, but has been most immediately useful to these young Russians. It is not yet clear how many will remain in Kyrgyzstan long-term. Today, most Russians are concentrated in Bishkek.

Dungans are a small but interesting minority. Ethnically Chinese and traditionally Muslim, most came to Kyrgyzstan in the 1880s to escape religious persecution by the Qing Dynasty. Some still speak Dungan, which is related to Mandarin Chinese but uses the Cyrilic alphabet. They number less than one percent of the population and are concentrated in small communities outside of major cities. Travelers will sometimes seek them out for their unique cuisine and traditional east-Asian architecture.

Germans are an old but fading community in Kyrgyzstan dating back to the 16th century, when Mennonite Christians arrived, fleeing religious persecution in Germany. They were later supplemented with Germans invited by Catherine the Great to modernize agriculture throughout the Russian Empire. The last wave of ethnic Germans came during World War II, when Stalin deported them from other locations in the USSR due to suspicions of conspiracy with the Nazis. One town not far from Bishkek, Rot-Form, became an island of German culture with a German-language school and German church. Since 1991, however, the number of ethnic Germans in Kyrgyzstan has fallen from 100,000 to only 8,000. Many ended up in Moscow, as they no longer speak German and instead rely on Russian.

Jews have been present in Central Asia since the 6th century when they arrived as traders and craftsmen on the Silk Road. In Kyrgyzstan, they once numbered about 40,000, when the population spiked due an influx of refugees in the 1940s. Today, only around 500 remain, with nearly all in and around Bishkek.

South Asians are also a relatively recent but conspicuous minority, mostly concentrated in Bishkek. These are mostly students who have come to take advantage of affordable tuition and a low cost of living. Although Bishkek’s institutions of higher education have long attracted these students, the war in Ukraine made it more difficult to study in Russia and Ukraine and many students that had studied in those locations transferred to Bishkek after 2022. Today, there are an estimated 12,000 Pakistanis and more than 14,000 Indians. In May, 2024, the community faced a wake-up call about underlying racism in the city when a mob of young Kyrgyz men, apparently trying to avenge injuries sustained by Kyrgyz men who had been in a street altercation with dark-skinned foreign students, attacked dorms where South Asian students lived, trashed their spaces, stole money and injured more than 40 people.

You’ll Also Love

Sheep Guts Won’t Kill You: A Guide to Seeing the Kyrgyzstan that Most People Don’t

The Kyrgyz are a Turkic people with a rich identity that revolves around their nomadic heritage. Although they were forcibly settled by the Soviets, some have maintained or returned to nomadic traditions. Other strong elements of their culture include faith in Islam that is heavily informed by previous (or present) belief in Tengrism, Zoroastrianism, and […]

The Women Who Shaped Kyrgyzstan

In traditional Kyrgyz culture, women have been long regarded as the keepers of culture, the managers of the household, and nurturers of children. Despite this vaunted position, Kyrgyzstan remains, overall, a patriarchal society and women are also often expected to be quiet and submissive. Below are several Kyrygz women who have broken that mold. They […]

Kuurdak: How The Kyrgyz Do Meat and Potatoes

Kuurdak (куурдак) is a traditional Kyrgyz dish and one of the oldest recipes found in Central Asia. It is eaten throughout Central Asia and particularly beloved as a national dish in Kyrgyzstan. This stewed meat dish is one of the easiest and simplest recipes to make. Traditionally, the meat used is mutton (lamb), horse, and/or […]

“Succulent Dog” and the Koryo Saram in Bishkek

It is well known that there is a significant Korean population in Kyrgyzstan today because Stalin deported Koreans living in the Russian Far East during World War II to prevent them from cohorting with the Japanese. These post-Soviet ethnic Koreans call themselves the Koryo saram. Koryo refers to Korea from the years 918 AD to […]

Kyrgyz Independence Day: Student Observations

Kyrgyz Independence Day is celebrated each year on August 31. It marks the date when, in 1991, Kyrgyzstan declared itself an independent republic and left the USSR. One of my fellow classmates at my university back in America, who had studied abroad a year prior, highly recommended attending Independence Day celebrations in Kyrgyzstan, noting that, […]