Kupala is an ancient Slavic holiday celebrating the summer solstice, or midsummer. Once part of a series of annual rituals, it marked and was believed to sustain agricultural cycles—essential to early human survival. Held as vitally important, these pagan traditions remained deeply rooted even after Christianization, technological change, and centuries of oppression tried to dislodge them.

Kupala is celebrated in common by Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians, though similar solstice festivals exist worldwide, reflecting a shared dependence on agricultural rhythms.

This resource combines language and cultural learning. The first section is a bilingual Russian-English text, with Russian phrases embedded in the English to build the vocabulary of Russian learners within a historical and cultural context. The second section features reflections by American students who observed Kupala celebrations held by refugees or minority groups outside their titular homelands—demonstrating how powerfully these traditions endure as expressions of national and individual identity, even far from their origins.

What is Kupala?

Slavic Gods and Spirits

Slavic mythology and paganism differs strongly in many ways from its western analogues.

The Primary Chronicle (ca. 1113) states that in Kyiv, the Grand Prince constructed giant statues to several deities in the 10th century:

|

|

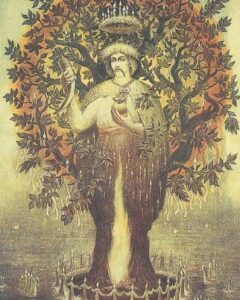

The list provided by the Chronicle is far from complete. Aside from the above, we can also find a deity called Сварожич (Svarozhich), who was считавшегося богом-кузнецом (considered a divine blacksmith) and who is mentioned in a handful of sources. And in addition, the ancient lords of Rus swore oaths not only by the name of Perun, but also by the name of Волос (Volos), бог скoта, торговли, и света (a god of livestock, commerce, and light; sometimes written as “Veles”). Ярила (Yarila; sometimes Yarilo) was a Slavic god of vegetation, fertility, and springtime.

Early Orthodox sermons make constant admonitions against worshiping Род и Роженица (Rod and Rozhenitsa). As with many Slavic gods, there is some debate as to whether these were truly gods or regarded simply as natural or supernatural forces to align oneself with. Both were associated with one’s ancestors (their names literally translate to “Kin” and “Birth-giver”). However, getting the population to disregard these entities was difficult as they were believed to have большую власть над судьбой семьи (wide-ranging powers over the fortunes of a household).

A similar debate about god vs. natural force revolves around the goddess Мокош (Mokosh), mentioned in the list from The Primary Chronicle. Some researchers believe that her name is related to мокнуть, the Russian word for “get wet.” Some of these argue that the Slavs were in fact recognizing the power of having the right amount of moisture in the soil, but not necessarily worshiping a personality. Others argue that the evolution of a personality perhaps happened only later and only in some areas.

Some folklorists call this tendency to focus on keeping in harmony with natural (and supernatural) forces “lower mythology.” Its importance has been disparaged by some, including the 20th century Russian scholar Evgeny Anichkov, who said that Russian paganism was особенно обеднела; ее боги были жалкими, ее культ и обычаи грубыми (particularly impoverished; its gods were pitiful, its cult and customs, crude).

However, it does not seem to have been so much crude as just very decentralized and complex. In Slavic paganism, capricious spirits rule the world. For example, the домовой (domovoi) was a дух дома, который мог как защитить, так и разрушить дом или семью (a house spirit that could protect as well as destroy the home or family). The rules of the domovoi were many and complex. For example, if a peasant moved to a new house and did not properly invite his domovoi along, the displaced spirit would become angry, sometimes убивая лошадей, нанося вред урожаю или создавая шум по ночам (killing horses, harming crops, or creating noise at night). One story tells of a woman whose domovoi would braid her hair at night and forbid her to undo the braid. The woman lived 35 years without washing or combing her hair. When she finally did, just before her wedding day, her mother came home to find her chocked to death. The domovoi was blamed.

Other spirits, just as demanding and capricious, were everywhere and unavoidable. They could be helpful but also потребовали соблюдения их особых правил (demanded their particular rules be followed).

These included the:

|

|

One common rule kept by the spirits was что свист был запрещен (that whistling was forbidden). The noise was said to disturb and attract spirits. To this day in Russia, свист – это табу, особенно в домах (whistling is taboo, especially in homes).

A common way to умиротворить сердитых духов (appease angry spirits) was to предложить им хлеб и соль (offer them bread and salt). Bread and salt were the two most important dietary staples for peasants and were commonly offered to guests as a show of hospitality and symbol of good will.

The Agricultural Cycle in Slavic Mythology and Kupala

This cautious mentality is not at all surprising. Especially in the northern lands of the Slavs, the growing season is very short and any derivation in the crop cycle can result in голод (hunger) or even смерть от голода (starvation). Much of early Slavic history was also marked by almost constant warfare; meaning that dealing with вторгшиеся войска (invading troops) and even competing сборщики налогов (tax collectors) was also a relatively frequent problem.

Thus, elaborate rituals were also conducted regularly to обеспечить обильный урожай (ensure bountiful harvests). In most Slavic cultures, holidays were held to mark, for example:

|

|

Solstices and equinoxes were particularly powerful as they heralded coming changes in the weather and непрерывность сельскохозяйственного цикла (the continuity of the agricultural cycle). Thus, the coming spring was celebrated before it even arrived, with Maslenitsa. This holiday, originally connected with the spring equinox, is still celebrated with surprising intensity throughout Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Round pancakes are feasted on in honor of the sun. Games, festivals, family visits, and more are held throughout a full week of celebration.

The summer solstice was also important to many pagan cultures, as it marks the day when summer is at its height and the days will now begin to shorten and descend into winter. Holidays still mark many Eurasian cultures, such as Wianki for the Poles, and, in Latvia, the summer celebration of Ligo is still the year’s major celebration and an expression of national pride. For the Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarussians, the celebrations were known as “Купала” (“Kupala”) or “Купалo” (“Kupalo”).

Some have argued that Kupala was a god of vegetation. Others argue that the name simply refers to the event. Both may be correct. In Russian, купаться means “to bathe” and ritual bathing is a major part of the holiday observances. On this day, it was believed, the sun imbues the water with special, health-giving powers. Some myths explained this by saying that, on this day, once a year, солнце купается в океане (the sun bathed itself in the ocean). Some scholars suggest the Купала was the Slavic version of Cupid and that the names Cupid and Купала are actually related. Others state that Ivan Kupala is a holiday celebrating Yarila, a more powerful Slavic god of vegetation, fertility, and springtime.

To celebrate the day, соломенные чучела были построены (straw effigies were constructed). These effigies would then приносились в жертву (be sacrificed). The pagans расчленяли и сжигали чучело, а пепел либо закапывали, либо топили (would dismember, burn, and either bury or drown the ashes). This was believed to be effective in ensuring that the upcoming harvest would be successful. Fire also marked a божественный аспект (divining aspect) of the holiday: couples would jump over bonfires and if they remained holding hands when they landed, they would soon marry. Single people would jump alone hoping for the flames to grant them luck in finding a partner.

One of the most famous Kupala traditions is поиск мифического цветка папоротника (the search for the mythical fern flower), said to bloom only on the night of the summer solstice. In Slavic folklore, it grants fortune, wisdom, and much more, even the ability to speak with animals. Legends claimed it охраняют духи (was guarded by spirits) and could only be found by те, кто прошел испытание храбростью или чистотой (those who passed a test of courage or purity). In reality, папоротники не цветут (ferns do not flower)—something widely known—making the tradition a symbolic pretext. Young people would venture into the forest together “searching” for the fern flower, and those who returned as male-female pairs считались предназначенными для брака (were seen as destined for marriage). On a night богатую символикой плодородия, (rich with fertility symbolism), the fern flower served as a socially accepted ruse for courtship and romantic pairing.

Another lasting tradition is женщины плетут венки из цветов (women weaving flower crowns), which are worn and later released into water or offered to the bonfire. Fire and water—both seen as очищающими и дающими жизнь (purifying and life-giving)—were central to the celebration. Men might also make crowns – although usually leaves from hardwood trees such as oak were used.

People feasted on seasonal foods and не спали до рассвета (stayed awake until dawn) to greet the rising sun, honoring its strength before the return of shorter, colder days. Надежда на окончательный триумф солнца (The hope for the sun’s eventual triumph) at the spring equinox was a key part of the ritual’s symbolism.

Kupala as a Mix of Christian and Pagan Belief

Particularly in Ukraine and Russia, когда в пришло христианство, эти языческие взгляды не исчезли (when Christianity came to Russia, these pagan beliefs did not disappear). This was despite the constant reprimands of the Church but also in part due to the Church’s own actions. For example, the church attempted to replace Kupala with a holiday that honored John the Baptist. This only strengthened the народное прозвище (folk nickname) that the peasants had already given John – Иван Купало (Ivan Kupalo) or, translated loosely, “John the Bather.” The straw man used in the pagan ritual is to this day known as “Ivan Kupalo.”

День Ивана Купала (Ivan Kupala Day) or Иванов день is today primarily celebrated in Ukraine and, to a lesser degree, Belarus and Russia. The holiday no longer falls on the marked on the summer solstice because the Orthodox Church linked it to праздник Рождества Иоанна Крестителя (St. John’s Day), which falls on June 24. In Russia, where the Orthodox Church still marks time by the old Julian calendar, this now corresponds to July 7 by the modern Gregorian calendar. The Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU) switched to the revised Julian calendar in 2023, moving fixed religious holidays 13 days earlier. Thus, Ukrainians now generally mark the holiday on June on the evening from June 23-24, the same day as celebrations in Latvia and Poland.

Whatever the actual origin, Ivan Kupala is an example of a сочетание язычества и христианства (mixing of paganism and Christianity), which is often referred to as двоеверие, a term that loosely translates to “double faith.”

Kupala in Modern Culture

Examples of pagan culture and symbols arising in modern culture are common. In Russia in recent years, языческие традиции в России возвращают себе популярность (pagan traditions are making a comeback) with the help of regional governments that have used festivals like Kupala to encourage tourism. In Ukraine, the tradition of Kupala is particularly pronounced as an expression of Ukrainian identity.

Kupala has found expression in commercial culture:

- In 2002, Herbal Essences shampoos released a Hочь Ивана Купала (Night of Ivan Kupala) shampoo that was marketed in Ukraine and Russia.

- In 2004, a Russian travel agency advertised a package for romantic travel asserting that “праздник по праву считается самым веселым и сексуальным в году” (“the holiday is truly counted as the merriest and sexiest of the year”) and offered a two-day, one night package of travel to the countryside for the holiday.

- Several movies have been made focusing on the holiday: В ночь на Ивана Купала (2020) and Вечір на Івана Купала (1968) being two.

- The 1968 Ukrainian film was based on “Вечер накануне Ивана Купала” (The Night of the Eve of Ivan Kupala; often rendered in English as “St. John’s Eve”), a short story by Nikolai Gogol.

- A Russian folk band performs under the name Иван Купала.

The holiday also still exists, of course, as a celebrated day with ancient traditions. Take, for instance, this 2020 news broadcast from Ukraine showing the holiday being celebrated:

or this video blog showing Kupala celebrated in Russia in 2023:

Ivan Kupala as Celebrated in Warsaw in 2024

This section was contributed by Alexander Neuman, a third-year Ukrainian student spending the Summer of 2024 with SRAS in Warsaw, Poland. His studies were supported by the U.S. Department of State Program for Research and Training on Eastern Europe and Eurasia (Title VIII). Alexander is pursuing a Master of Arts in International Security at George Mason University.

In 2024, Warsaw’s Ukrainian community arranged a celebration of Ivan Kupala Night, an Eastern Slavic midsummer festival that dates back to pagan times but still remains part of many Slavic cultures. The holiday was arranged primarily for Ukrainians displaced from Ukraine by the war. However, all who were interested were welcomed to the celebration including local Poles and SRAS students studying on SRAS study abroad programs in Warsaw at the time.

Attending this event was eye-opening for many reasons. This was a first-hand experience of authentic Ukrainian culture, as practiced by Ukrainians. It was also a reminder, however, that despite even the trauma of war and displacement, culture lives on. The festival’s bonfire, traditional dances, and floating wreaths celebrated heritage, unity, and resilience.

Cultural Continuity in Exile: The Ukrainian and Belarusian Communities in Poland

I remembered the long jump in middle school P.E. class as I leaped over the flames and skidded to a halt on the sandy Poniatowka Beach of the Vistula River. The Ukrainian attendees cheered for me, even though I nearly fell backward into the fire pit. The occasion was Ivan Kupala Night, an eastern Slavic holiday with pagan roots that celebrates Midsummer.

What made this celebration special was that it was organized by the Ukrainian expatriate community in Warsaw, Poland. Fortunately, I learned about Ivan Kupala the previous week from an assigned reading in my B1/B2 Ukrainian class held by SRAS and the Slowianka Language School.

Ukrainians, Belarusians, Russians, and certain regions of Poland itself celebrate Ivan Kupala despite all of these countries now being resolutely Christian. Indeed, the following Saturday, I attended an all-night Ivan Kupala festival organized by Warsaw’s Belarusian community called Varushniak. The holiday serves as a venue for multiple generations to have fun and celebrate their culture, with all four languages heard at both events.

The bonfire is the center point of the celebration, symbolizing the burning away of the previous season. It is also serves as an obstacle which young couples, who could be a literal or figurative ‘bride and groom’ pairs, hold hands and jump over for good luck. However, individuals constantly leaped over it as well, just for fun. In between the constant stream of jumpers, the community formed circles around the fire, holding hands and dancing to traditional Ukrainian and Cossack songs over the speakers.

A second component of Ivan Kupala is the vinok. Unmarried girls will each create one of these wreath-style headbands out of straw and flowers, symbolizing maidenhood. They would then fix a small lit candle to them and release them into the Vistula, with the lights of downtown Warsaw and the riverside promenade of Powisle shining from the opposite bank. Knowing how to properly construct these is important as a sinking wreath symbolizes bad luck, a floating one – a good marriage in the works. I didn’t see any sink.

The holiday celebration was organized by Euromaidan Warsaw, one of several Ukrainian non-governmental organizations in Poland, and featured a cookout, Ukrainian music, and an open microphone for Ukrainians to share their singing talents. A small flea market sold Ukrainian souvenirs, paintings, blue-and-yellow wristbands, and traditional embroidery like vyshyvanka shirts and rushnik traditional towels, as well as other handmade crafts, with all proceeds directed to the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Language, Identity, and Solidarity in a Time of Crisis

Even in such a merry summer atmosphere, the war next door was in the air. It hung over the majority of my conversations when I asked Ukrainians how long they’ve been in Poland: “two years.” Nothing more needs to be said. One of the consequences of the full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022 was a surge of interest in learning the Ukrainian language and culture around the world, starting with Duolingo for me. The same cloud of displacement hung over the Belarusian celebration: many of the Varushniak attendees I spoke with arrived in 2020, when the Belarusian government cracked down on massive protests against electoral fraud, and which represses the Belarusian language as a sign of disloyalty to the regime.

This event was one of my many observations that reinforced how SRAS described Warsaw as a “destination for the millions of Ukrainians who have sought refuge in Poland, boosting the amount of Ukrainian to be heard in that city.” After just two weeks of formal language study with SRAS, Ivan Kupala was the first time I practiced speaking Ukrainian in public. The result was unlike anything I ever experienced on previous travel abroad.

For the first of many times this summer, my Ukrainian interlocutors thanked me and shook my hand for learning their language. The depth of this response illustrated the significance of taking the time to learn the language of a nation fighting for its existence. This program is not just improving my communication skills: it is helping me demonstrate my respect for and build rapport with Ukrainians, while representing my country in a positive light to them. My objectives to learn their language at a rapid pace aligned perfectly with its diaspora’s mission of keeping traditions alive in a time of dislocation and uncertainty.

Ivan Kupala as Celebrated in Kazakhstan in 2023

This section contributed by McLean Brown, who spent the summer of 2023 traveling Kazakhstan, researching folklore in the Altai Mountains, and studying the intersection between language and national identity in Kazakhstan.

In July 2023, as a volunteer on an ethnographic expedition studying the folklore of Old Believers in Eastern Kazakhstan, I was invited to attend and participate in the Ivan Kupala Day celebration. The holiday is a Slavic midsummer event, and this particular celebration is organized by the Russian Ethnographic Museum in Ust-Kamenogorsk, Kazakhstan. We attended on July 6 at the beautiful Left Bank Complex on the Irtysh River.

The Multi-Culturalism of Ust-Kamenogorsk in Kazakhstan

We began our experience with a guided tour of the park, where we were told that the city has a long history of multiculturalism. In fact, the city itself has two names – Ust-Kamenogorsk and Oskemen (the Kazakh name). Both are official, and they are often used interchangeably by those who live in the area. Kazakhstan recognizes both Russian and Kazakh as official languages on equal footing. Thus, it makes sense that the names would be interchangeable. However, if you purchase tickets to go here, they will most likely say Ust-Kamenogorsk and the Russian name was the one that everyone, including locals addressing out group, used when speaking with us. Thus, for clarity, this is the name I will use in this article.

Located just around 80 miles from the Russian border, Ust-Kamenogorsk has a long history of multiculturalism. It only recently became a Kazakh-majority city and Russians still make up about 45% of the population. The city is dotted with both mosques and Orthodox churches.

After learning about the history of the park and city, our guide took us to where the celebration would soon begin. Claiming our spots in the grass, I noticed that the crowd around us was a vibrant mix of people of all ages and backgrounds. Most of the group, the performers, and the organizers were Russian, but there were still many Kazakhs in the crowd. When speaking with them, many of them said they enjoyed attending the celebration every year. Despite the Slavic roots of Ivan Kupala Day, some Kazakhs are incorporating it into their culture in Ust-Kamenogorsk. Similar incorporations can be seen with the celebration of Maslenitsa in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, for example, and even with New Year Celebration, which was first brought to Central Asia in the 1800s by Russians and today stands as one of the largest and most important celebrations of the year.

Dances, Games and Crafts for Ivan Kupala in Kazakhstan

The festivities began with the arrival of groups wearing traditional Slavic sarafans performing conventional Slavic folk songs. Since these singers were local women from nearby villages who had learned these songs from their parents and grandparents, many themes came from Cossack folklore. The Cossacks came from southern Russian and Ukrainian peasants that sometimes served as mercenaries and garrison units for the Russian Empire. Thus, the lyrics these women beautifully sang often dealt with returning from war to find your family gone, spending many days on horseback, and living a life on the road. Even without understanding every word, the way these women sang took my breath away, and I could genuinely feel the emotion behind the song.

After the women had performed a few songs, the event organizers returned, announcing that the first set of dances would begin in a few moments. Once the music started playing, everyone stood up from their seats in the grass. The master of ceremonies instructed us to join hands with the people around us and form a circle. We then began to move in rhythm with the music and lyrics. For the next half hour, everyone participated in various circle dances, all intended to represent the movement of time and the seasons. According to the organizers, these rituals and dances were believed necessary for time to continue moving, as the sun would refuse to move into the next season if the dances did not occur. This circular year and the corresponding passage of time is still a crucial part of the folklore surrounding Ivan Kupala and other folklore today.

Once the dances were over, the folklore ensemble began singing. At the same time, the announcer instructed the children how to play traditional Slavic games, including ones explicitly meant for Ivan Kupala Day with circular movements and rhythmic chants. I made my way to the area where several people were selling handmade crafts, walking past a food cart selling corn, cotton candy, ice cream, and various sodas on my way. Interestingly, there was no other food available at the event itself, which was fairly long. Hard boiled eggs are often traditionally eaten for Ivan Kupala, as are dumplings (both symbolizing fertility). However, neither were available at the event.

The craft vendors were happy to tell you about their jewelry, dolls, crocheted items, wood-carved whistles, and souvenirs. After studying my options, I bought a crocheted Cheburashka, a famous Russian cartoon character, to bring back home for 900 tenge ($1.99).

Wreathmaking Competition

Now that the folklore ensemble had finished singing, it was time for the wreath-making competition to begin. The announcer invited any women who wanted to participate to head off into the outer reaches of the meadows and pick their flowers. Several dozen participants accepted the challenge, the younger ones racing after each other to get the most colorful flowers. After she had collected enough, each woman began to weave her wreath, placing it upon her head after completion. According to the tales people told at the festival, these wreaths hold one’s ancestors inside them. Before the conclusion of the Ivan Kupala Day festivities, each woman must throw their wreath into the river, or else forest nymphs will jump on their head, causing them to suffer from incredible headaches for the following year. This tradition, like many others, comes from the Slavic belief that Ivan Kupala Day is a threshold day, when the world is passing from time to another, and spirits are thus more active than usual, causing the connections between the living and the dead to become stronger. Midsummer is celebrated in many cultures as a threshold day – a concept that permeates nearly all cultures.

Once everyone had completed their wreaths, the women lined up before the crowd. Each introduced themselves while showing off the wreath that they had made. From tiny, neat wreaths to huge, flashy ones, various styles of wreaths stood on display. After all the participants had introduced themselves, the crowd chose a winner with their applause, and everyone celebrated together, taking pictures of the gorgeous wreaths.

Conclusion of Ivan Kupala: Fire and Water

After another round of circle dances, the sun began to slip behind the mountains. Everyone slowly started making their way toward the bonfire that had been prepared, eagerly anticipating the burning of the effigy. While the master of ceremonies explained that it symbolized the year’s harvest and must be burned for there to be a good harvest the following year, the effigy of straw was carried in and placed against the firewood. The effigy itself was dressed like a traditional Cossack man, including the strong mustache that they have often been associated with. People were allowed to come up and touch the effigy, with many also taking the chance to get a picture with it.

The event organizers then began to lead the crowd in a chant used during the lighting of the fire. As the crowd swayed back and forth, a man entered the circle with a torch. Despite initially struggling to start, the fire soon roared to life, bringing cheers and shouts from the crowd. Three men began to roll an axle with a large wooden wheel attached to it around the fire. The wheel, yet another representation of the circular year, caught flame itself, and the men continued to roll it until too much of it had burned away for it to continue moving.

As the fire enveloped the effigy, it burned away the previous season’s spirit and harvest, inviting the world to transition into the next season. Even with the various backgrounds and languages of everyone in attendance, everyone was united in this moment of awe as we took part in a tradition with roots that trace back over a thousand years.

Slowly, the fire began to tip over and fall, inviting yet another roar from the crowd. One by one, and sometimes two by two, people began to run at the fire and jump over the flames. According to traditional beliefs, individuals who jump over the fire are rewarded with strength and fertility, and couples who do so without letting go of each other’s hands are said to go on to have a long and joyful relationship. Each time someone would run up and jump, the crowd would cheer them on and congratulate them for their bravery. The fire eventually died out, and everyone went home after the women had thrown their wreaths into the river. Still, that night’s energy and good spirits lived on for several days for everyone there.

Recommended Further Reading

See articles on this site about Ligo and Wianki, other midsummer celebrations in Eurasia.

See our resource on spring equinox celebrations.

Also see the following recommended books below:

You’ll Also Love

Draniki, Latkes, Kartupeļu Pankūkas: The Simple Deliciousness of Potato Pancakes

Potato pancakes dominate coffee shop menus in Riga, Latvia—and for good reason! Meticulously prepared using grated potatoes, eggs, and flour, these pancakes are crisped to a brilliant golden hue, reaching a level of perfection that rivals the shining sun itself. The mouthwatering allure of this delightful dish is recognized worldwide. Following their inception in Eastern […]

Olivier and Rasols Salads: Holiday Traditions With Fascinating Histories

Russia’s Olivier Salad (Салат «Оливье») and Latvia’s rasols are well-known staples of their respective cuisines and common additions to holiday tables. Today, the recipes for both are quite similar, with chopped vegetables, egg, and meat dressed with mayonnaise. Olivier is now eaten throughout the former USSR and has even become common as “Russian Salad” in […]

Heavenly Hundred Mourners In Kyiv

Hundreds of people came to Kyiv’s Independence Square, or, in Ukrainian, Maidan Nazeleznosti for the third anniversary of the day snipers killed 100 protesters during the EuroMaidan Revolution, on February 18, 2017. The deceased are commonly known as the “Heavenly Hundred.” The date of thier death is now marked every year by mourners returning to […]

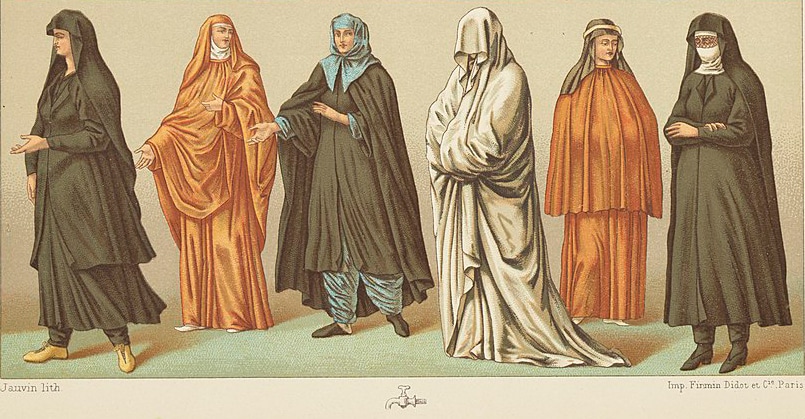

The Habits of Nuns in Catholic and Orthodox Traditions

Despite their cloistered livelihood, nuns have found their way into many veins of popular theater and movies. However, their usual depiction, wearing black habits with a veil and carrying a rosary, is not accurate for all nuns. It is true that the symbolic meaning of the habit is consistent across both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox […]

Kulich, Paska, Nazuki: The Easter Breads of Eastern Christianity

Easter breads such as kulich, paska, choreg, and nazuki are delicious Easter traditions. Easter is by far the most important religious holiday for those practicing Eastern Christianity. In addition to church services and egg dying, the holiday is also marked across the cultures by ritual bread baking. Despite the wide geographic area covered by Eastern […]