Russian folklore is rich with stories of spirits, haunted places, and supernatural forces that influence daily life. These beliefs shape how certain locations, from uncivilized wilderness to abandoned homes, are viewed in the collective imagination. Unclean spirits, or нечистая сила, are believed to settle in ominous spaces like crossroads, swamps, and even ordinary houses if the proper rituals are not observed. There are also place spirits such as the домовой, a house spirit, which can be a benevolent protector or a vengeful force. Even trees and battlefields hold significance, with spirits from the past lingering in these places. From the Moscow Kremlin to the haunted village of Kukoboi, Russia’s haunted history is steeped in tales that blur the line between the natural and supernatural.

The bilingual resource below is provided to assist students in understanding the how Russian folklore envisions these things as well as how the Russian language expresses them!

Types of Haunted Places in Russian Culture

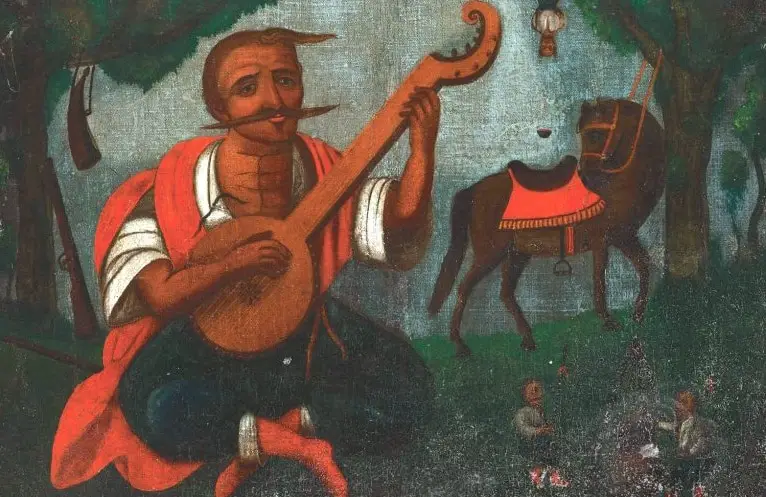

According to Russian folk beliefs, нечистая сила (unclean spirits; sometimes referred to with the shortened “нечисть”) prefer to settle in evil places or places viewed as conducive to evil.

These can be categorized in several broad categories (not all of which are listed here). One consists of uncivilized places or places not conducive to civilization. These include: дикие места (uncultivated and/or unsettled grounds), трущобы (thickets), трясина (bogs), and непроходимые болота (impassable swamps). As a large, wet, cold country with a relatively thin population, Russia has always had many of these places. Another category deals with the concept of предел (threshold) – where one area crosses to the next. These include развилки дорог (crossroads), мосты (bridges), околицы деревень (borders of villages), края полей (edges of fields), пещеры (caves), ямы (pits), and колодцы (wells).

Crossroads are traditionally considered places of evil across Europe because, in ancient times and into the Middle Ages, people who died while traveling were traditionally buried at the next crossroad. As the places became associated with death, tales of неупокоенные души, которые скитаются у развилок дорог (restless souls wandering at the crossroads) and of убийцы, которые прячутся в засадах у развилок дорог (murderers lurking at crossroads) became common.

Places that are considered опасный (dangerous) are also places that might be haunted. These include пруды (ponds) and especially водовороты (whirlpools), which are often associated with утопление (drowning), perhaps at the hands of spirits inhabiting them. Places known for their риск пожара (risk of fire) such as места за печью и под ней (places behind and under an oven) and the баня (bathhouse) are often settings for grizzly tales of evil spirits burning people alive or even flaying off their skin. Хлева (barns or cattlesheds – note the irregular plural of this word), where people are at риск обрушения (risk of trampling), are also sometimes inhabited by precocious spirits.

The Domovoy: House Spirits and Haunted Homes

One difference between haunted houses in Russian culture and western culture is that sometimes, in Russian culture, houses are haunted not because of a зловещее убийство (grizzly murder) or other ужасное событие (terrible event) connected with it, but simply because all homes naturally have spirits individually called the “домовой” (house spirit). Cats can see the домовой, though humans usually can’t. Some Russians believe that when a cat plays, it is playing with the домовой.

While generally positive or neutral spirits, домовой can become evil if not treated well. When moving to a new house, the домовой should also be invited. If not invited, the home becomes haunted by the slighted домовой, who can be extremely dangerous. Anyone attempting to reside or sleep in an заброшенный дом (abandoned house), risks смерть (death), ранение (injury), or безумие (madness) at the hands of the спровоцированного домового (provoked house-spirit).

Famous Haunted Places in Russia

Some places are посещается (haunted) by духи умерших (spirits of the deceased). The Moscow Kremlin is among one of them – where the ghosts of old Russian czars like Alexander II and Ivan the Terrible have been seen. An official working late one night in 1994 in the room under Lenin’s former office обеспокоили (was disturbed by) by звуки шагов над ним (sounds of pacing above him). Sure that this was Lenin’s ghost, the official stopped staying late at the office for fear of disturbing the spirit.

The village of Kukoboi is perhaps the place with the greatest concentration of haunted places in Russia. This village, in the Yaroslavsky Oblast (some 200 miles from Moscow), is considered the home of Баба-яга (Baba Yaga), an old witch immortalized in Russian fairy tales who, among other things, похищает (kidnaps) and sometimes eats children. However, she is also sometimes helpful (or tricked into being helpful) to travelers who treat her well. Kukoboi has several haunted houses, spots, and even a haunted library.

Former World War II battlefields are also known as места скопления духов (gathering places for ghosts). Here, many people were killed and often not buried properly, leaving their ghosts to remain on earth.

Differences Between Russian and Western Hauntings

In most cases, the spirits who inhabit haunted places in Russian culture are not necessarily evil. Often, if treated with respect and reasoned with, they can even turn into allies of those who encounter them. Perhaps for this reason, horror and especially slasher films have typically done poorly at the Russian box office. Those that do relatively well usually harken to the psychological horror of classic Russian literature or at least to its tradition of showing the supernatural as a force that can be reckoned with and that very often reflects our own faults and shortcomings.

You’ll Also Love

Fitness and Health in the Russian Language

In recent years, gym and fitness options have proliferated across Eurasia. Travelers interested in maintaining their fitness regimen while abroad – whether they are visiting Latvia, Georgia, or even Kyrgyzstan, should have no problem doing so. It does help to know a bit about these gyms and it pays to know some of the Russian […]

Russian and Ukrainian: Differences and Similarities

Sharing common roots, Russian and Ukrainian, at first glance, look very similar. This is not so. In reality Russian and Ukrainian have more differences than similarities. The following is an article that originally appeared on Russian7.ru (Русская Семерка). The original can be read here. The following translation to English has been provided by Lindsey Greytak, […]

Why Do Russians Shout «Горько!» (Bitter!) at Weddings?

The following information originally appeared as part of a longer article on The Village, a Russian-language lifestyle publication. It has been adapted by SRAS and translated here by SRAS intern Mae Liou. Gerda, a professional Russian wedding emcee: People often ask me about this, so for some time now I’ve been aware of several […]

Самый лучший разговорник – The Best Phrasebook Ever

The following list of phrases are meant as educational humor. Some are just silly, some are useful, some will be understood by all, and some only by those who have spent time in Russia. Some of these have been around online as jokes for some time – others were added based on common experiences that […]

Kupala: Ancient Slavic Midsummer Mythology and its Modern Celebration

Kupala is an ancient Slavic holiday celebrating the summer solstice, or midsummer. Once part of a series of annual rituals, it marked and was believed to sustain agricultural cycles—essential to early human survival. Held as vitally important, these pagan traditions remained deeply rooted even after Christianization, technological change, and centuries of oppression tried to dislodge […]