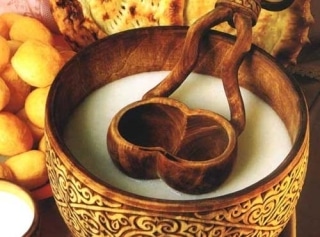

Russia and Central Asia offer what can seem to be a bewildering selection of dairy products in their transnational food cultures. An area of special note, and often one of the strangest to Westerners, is the seemingly never-ending assortment of fermented milk drinks and products in the gastronomic repertoire. To cut down on the brow-furrowing and sometimes taste-bud-curdling excursions to your local import store, we’ve produced the following short but fairly comprehensive guide to the Russian and Central Asian fermented milk market.

Prostokvasha

(Простокваша)

It is probably most instructive to begin with prostokvasha. Prostokvasha is actually not one product, but rather a blanket term for a variety of fermented milk products that, as the Russian “просто” (simple) implies, are quite simple to ferment, which is what the “кваша” portion of the name refers to: “сквашивание” (souring or fermenting).

The simplest prostokvasha is made simply by allowing milk to sour in a warm place. However, this can be dangerous, as the fermenting microbes in this case come from the atmosphere and can therefore contain any bacteria, even harmful ones. Without regulating the bacteria or the souring process, the taste of the final product is also hit-or-miss. Therefore, most milk products considered prostokvasha are made by first boiling whole or otherwise unprocessed milk and then heating it for several hours (4-8) while adding selected cultures. Sometimes these cultures come from store-bought yogurt with active cultures or can come from commercially bought bacterial cultures. Prostokvasha is mostly used for drinking, often for its healthful dietary properties: healthy bacteria can improve digestion and dairy fats provide a good source of energy.

Kefir

(Кефир)

Kefir is perhaps the best-known of Russia’s fermented milk drinks. It is consumed across Eastern and Northern Europe and has also become popular in South America, where immigrants from the former Ottoman Empire and Eastern Europe introduced it. In recent years, kefir has spread more widely in the West, driven by globalization and growing awareness of its health benefits.

The word kefir comes from the Turkish köpür, meaning “foam”—a fitting name, as fermentation makes the drink naturally carbonated. This process produces small amounts of alcohol, typically between 0.5–1%, though levels can approach 3% if the mixture ferments longer, is sealed tightly, and shaken frequently.

Kefir has the consistency of thin yogurt and a tangy, sour taste that intensifies with longer fermentation.

Traditionally, kefir is made by fermenting milk—of any type, even soy—with кефирные зерна (kefir grains). These are symbiotic clusters of yeasts and bacteria encased in fats, proteins, and sugars. The practice began with shepherds in the northern Caucasus, who noticed that milk carried in leather pouches would ferment into a frothy, yummy drink. They began isolating grains that formed at the bottom and adding them back to fresh milk, much like bakers save dough from one sourdough batch to start the next. (You can even buy кефирные зерна on Amazon.)

Over time, kefir-making moved from shepherds’ pouches to household kitchens. Today, it can be made in any loosely covered, acid-resistant container. Milk and kefir grains are combined, leaving space for expansion, and left at room temperature for about 24 hours, with occasional shaking. Once fermentation is complete, the grains are strained out, then reused to start new batches. Because kefir grains multiply during fermentation, new starters are easily shared or sold. However, creating them from scratch is nearly impossible unless you are a Caucasian shepherd.

In Russia, production often continues to a second stage: the strained kefir is added to fresh milk and left to ferment another 12-18 hours. This produces a larger, richer batch and allows the grains to be removed before adding flavorings like sugar or lemon, which can damage them.

Modern, commercial kefir no longer relies on grains. Instead, manufacturers use precisely measured cultures of bacteria and yeast to ensure consistent flavor and texture.

Whether homemade or factory-produced, kefir can be drunk plain or used in cooking—especially as a substitute for buttermilk. Some people let it sit longer to thicken and sour further, but note that unrefrigerated kefir keeps for only two to three days.

Toplenoe Moloko

(Топлёное Молоко)

Toplenoe moloko is not actually fermented, but it is sold alongside fermented dairy products and serves as the base for the fermented ryazhenka (see below). The common English translation, “baked milk,” is somewhat misleading—топлёное literally means “rendered” or “clarified.” A better term would be “clarified milk,” as the drink is made by slowly heating whole milk so that water and some milk fats evaporate, much like in the preparation of clarified butter.

While industrial production of toplenoe moloko involves pasteurization and constant stirring, it is quite simple to make at home. The result is a creamy, caramel-flavored, beige-colored drink that has been enjoyed in Slavic countries for centuries. Traditionally, it was made in a “Russian” oven, which provided the even, sustained heat ideal for the process.

To make toplenoe moloko, first bring whole milk to a boil. Then, maintain strong, steady heat—hot enough to promote slow caramelization but not boiling—for several hours. This can be done in two ways: pour the boiled milk into a preheated thermos and let it sit for 4–6 hours; or heat the milk in a covered dish in the oven for at least 1½ hours.

Each method has potential pitfalls: the thermos must retain heat well, or the milk won’t clarify properly, while uneven oven heating can cause excessive evaporation or protein breakdown.

The drink’s distinctive flavor and beige hue come from the chemical reactions between milk sugars and amino acids during prolonged heating. These reactions create melanoidins—brown, heavy molecules that give toplenoe moloko its rich color and creamy texture. Thanks to these reactions, it also keeps remarkably well, lasting up to five days at room temperature—much longer than fresh or boiled milk.

Although it is most often consumed as a drink, toplenoe moloko is also used in baking пироги (pies or turnovers), as well as in creams and sauces. It can also be fermented to make another Russian treat – ryazhenka.

Ryazhenka

(Ряженка)

Ryazhenka is fermented toplenoe moloko, and in taste and texture is very much like unsweetened yogurt. Its origins are likely in the lands that now comprise Ukraine, where it has long been a staple of the very old civilizations that arose there. Originally made by heating milk and cream in special earthenware pots called “глечик” (glechik), the liquid was done when it lost the beige color characteristic of toplenoe moloko. Then a bit of sour cream is added and the mix ferments for 3-6 hours.

This process differs a bit from industrially made ryazhenka, in which fermentation is induced through the addition of thermophilic streptococci bacteria and cultures of lactobacillus bulgaricus, a bacteria widely used in making yogurt. By the end of fermentation, ryazhenka gains a brownish-yellow color and a sharp, sour taste.

Snezhok

(Снежок)

Source: www.100best.ru

Snezhok is essentially very sweet prostokvasha, created by heating sterilized milk with the addition of the same bacteria used to make ryazhenka and sour cream. To complete snezhok, however, generous amounts of sugar and/or berry-flavored fruit syrups are then added. As such, this is one of the more popular fermented milk products among children, and often consumed for breakfast. This may also help explain its rather cute name; “snezhok” means “snowball,” and is so named because the end product, so long as only white sugar is added, is as white as snow.

Tan

(Тан)

Tan is originally an Armenian drink but is common across Russia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia today. Made with either cow or goat milk, mixed both with the same bacteria as used in sour cream and ryazhenka as well as lactose-fermenting yeast. Lastly, a bit of salt or salt water is added to sharpen the taste, making it nearly the polar opposite of snezhok!

The popularity of tan over its wide geographic area is only increased by the fact that the drink has a unique combination of health benefits due to the nutrients provided by the salt addition and their interactions with the very biochemically active fermenting agents. It is widely used as a cure of an upset stomach and is a popular hangover cure.

Kumys

(Кумыс)

Kumys is Central Asian in origin and a delicacy consumed widely among those peoples descended from the great nomadic tribes of the steppes. In fact, its importance to Kyrgyz history can be seen in the legend that Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, is named for the spoon used to churn kumys as it ferments. The word kumys itself likely derives from the Kumyks, a Turkic people of modern-day Dagestan and Northern Ossetia. The drink itself is ancient, mentioned as early as the 5th century BC by the Greek historian Herodotus in The Histories.

Kumys is fermented mare’s milk. Nomads traditionally carried it in leather bags fastened to their saddles, where the warmth of the horse and the constant motion aided fermentation, creating its distinctive flavor and texture. Another common method was to hang partially filled skins on doorframes, where passersby, knowing what these skins signaled, would give them a good punch to ensure continued successful fermentation.

Historically, kumys was both a daily staple and a ceremonial drink, consumed in great quantities during weddings and tribal gatherings. Today, mare’s milk is scarce even in regions where kumys remains popular, so commercial producers often substitute cow’s milk enriched with sugar to replicate the higher lactose levels of mare’s milk.

Kumys was a dietary staple, but was also called for in massive quantities to mark any large event such as a wedding or a gathering of the tribes. In the modern day, mare’s milk is a scarce commodity, even where kumys is popular, so industrial production of the drink often uses cow’s milk fortified with extra sugars, in order to simulate the amount of fermentation sugars produced by the higher lactose concentration in mare’s milk.

Kumys has a light yet sour flavor, sharpened by its mild alcohol content—typically 1–2.5%, the highest among traditional fermented dairy drinks. The higher alcohol level comes from the sugar-rich mare’s milk and the constant agitation of fermentation. Comparable to a regional beer, kumys is served cold in small, handleless cups called pivala and plays a central role in Kyrgyz hospitality rituals. At the end of a kumys-drinking session, guests traditionally pour their remaining dregs back into the main container both to avoid waste and to ensure that enough remains for future visitors.

Suzma

(Cузьма)

Suzma, also known as qatiq in some cultures, is a thick, tangy dairy product common throughout Central Asia, the Caucasus, and parts of Eastern Europe. Closely related to yogurt and sour cream, it is sometimes referred to in English as “yogurt cheese,” as, while it is technically yogurt, it has a consistency more resembling forms of farmer’s cheese or quark. It serves as both a standalone dish and a base for soups, sauces, drinks, and much more. The word suzma comes from the Turkic verb süzmek, meaning “to strain,” perfectly describing its method of preparation.

Suzma is made by straining yogurt through a cloth or fine sieve to remove excess whey, leaving behind a smooth, dense curd. This process concentrates the milk’s proteins and fats, resulting in a product with a creamy consistency and pleasantly tart flavor. The longer it is strained, the thicker the suzma becomes. It can range from a soft, spreadable texture like cream cheese to something more solid and crumbly like feta, depending on local preference.

Traditionally, suzma was made using goat milk. Today, cow’s is most common. The straining cloth would be hung in a cool, shaded spot, allowing gravity and time to do the work. The leftover whey was fed to animals or used in cooking, ensuring that nothing went to waste.

Suzma is eaten plain, spread on bread, or mixed with cream, salt, herbs, or vegetables. In Uzbekistan, it is made into cholop soup in the summer. When thinned with water and spiked with salt, it becomes ayran; when strained further, salted, and dried, it becomes kurut (see below). Suzma remains a staple in Kyrgyz and Kazakh cuisine, sold both fresh and packaged in markets, and used in a variety of ways.

Kurut

(Kурут)

Kurut (also known as kashk, kurt, kurtob, qurut, and other names) is a traditional dairy product common across Central Asia, the Caucasus, and parts of Eastern Europe, known for its long shelf life and distinct salty-sour taste. Among the Kyrgyz and other Turkic peoples, it is both a practical food for nomadic life and a symbol of hospitality, often offered to guests alongside tea and/or dried fruits. Some add it to tea.

Its name derives from the Turkic word “kurutmak,” meaning “to dry,” a direct reference to the fact that it is made by drying small balls of strained, salted sour milk or yogurt. Traditionally, the process begins with straining and salting suzma (see above) into a think paste and shaping it into small spheres or discs. These are left to dry in the open air under the strong Central Asian sun until they harden completely, creating a product that can last for months, even in the heat of summer.

For nomads, kurut was an ideal food: lightweight, nutritious, and durable. Travelers and herders could easily carry it on long journeys, rehydrating it in water, milk, or tea when needed. Its intense, salty flavor also made it useful as a seasoning or base for soups and sauces. It can also be eaten straight and remains a favorite street food, especially for children. In this form it is a delicacy – with an very intense flavor and saltiness and a chalk-like consistency.

Today, kurut is sold in markets and roadside stands. Modern variations may include herbs or spices, but traditionalists prefer the plain version made only from fermented milk and salt. In rural areas, kurut is still made by hand and with the sun, while commercial producers such as Arashan use dehydrators to ensure consistency.

Although its texture and saltiness can surprise first-time tasters, kurut remains a beloved staple of Central Asian cuisine.

Tvorog

(творог)

Tvorog is the only entry here that is not commonly drunk or used to create drinks. However, it is created in much the same way the other entries and is an absolute staple of Russian, Ukrainian, and other Eastern European cuisines and has been for centuries.

Tvorog is made by fermenting milk with the same bacteria found in yogurt until the milk curdles naturally, then heating it gently to separate the curds from the whey. The curds are collected and strained through cheesecloth, producing a soft, crumbly mass with a clean, slightly sour taste. Its texture can vary depending on how long it was heated and how long it is drained—ranging from moist and spreadable to firm and dry. Tvorog has typically been made from cow’s milk and is today widely produced commercially throughout Eastern Europe.

Rich in protein and calcium yet low in fat, tvorog is highly nutritious. It is eaten plain, mixed with cream, sour cream, honey, preserves, and/or fresh or dried fruit for breakfast, or used as a filling for classic Slavic dishes such as syrniki (fried curd pancakes), vareniki (filled dumplings), and pascha (an Easter dessert made with tvorog, butter, and sugar).

Fermentation for Preservation and Taste!

Clearly, fermented milk is a big deal in Eurasia… a really big deal! While there is no definitive answer as to exactly why this is, a key to the puzzle most likely lies in the fact that fermentation, like pickling or salting, is just another means of preservation. In times before commercial refrigeration, when most were living at a subsistence level, one had to keep produce as long as one could to reap its benefits to the fullest. The fermentation of milk can add a few days to the shelf life of milk by at least controlling the fermentation process that will naturally occur. Milk and dairy products, as sustainable sources of protein and other nutrients, have traditionally made up a great deal of the diets of the Eurasian people. In Kyrgyzstan, they still account for nearly half of all calories consumed.

Slightly spoiled ryazhenka or kefir can also still be used to make baked products like “пироги” (stuffed pies) and “блины” (bliny). Some say these slightly spoiled products, in fact, make the best versions of these traditional dishes, as the carbonation can make for a very light and fluffy dough while the baking process kills all bacteria present.

For many Westerners, most fermented milk products will be an acquired taste to say the least. For starters, though, maybe go with some toplenoe moloko, which, as you now know, is not actually fermented and has a rich, caramel taste. If you like that, why not dip both feet in and try some snezhok, which is nice and sweet and probably the mildest introduction? Keep building up your tolerance and branching out, and soon you may join the ranks the Russians, Central Asians, and the great peoples of the Caucasus as a lover of fermented milk!

Our Favorite Fermented Milk Videos

Video about the industrial production and health benefits of kumys.

A recipe for oladushki (a kind of fried pancake) made from snizhok.

Making bliny with kefir!

You Might Also Like

SRAS has developed the test below to help you gauge your Russian language skills! Anyone interested in gaining more knowledge should check out the the resources under “language” on our main menu including especially our Resources for Students of Russian and the Russian Talking Phrasebook. You can also sign up to study Russian online or […] The following TORFL reading comprehension practice test has been developed by SRAS based on the official TORFL test to help you gauge your knowledge of the Russian language! Anyone interested in gaining more knowledge should check out the the resources under “language” on our main menu including especially our Resources for Students of Russian and […] The following TORFL grammar and vocabulary practice test has been developed by SRAS based on the official TORFL test to help you gauge your knowledge of the Russian language! Anyone interested in gaining more knowledge should check out the the resources under “language” on our main menu including especially our Resources for Students of Russian […] The below test has been developed by SRAS to help you gauge your knowledge of the Russian language! Anyone interested in gaining more knowledge should check out the the resources under “language” on our main menu including especially our Resources for Students of Russian and the Russian Talking Phrasebook. You can also sign up to […] Olga here turns her attention to the modern Russian circus, describing what it is like to attend a contemporary performance, from the atmosphere inside the circus building to the acts that still draw enthusiastic audiences today. Written in simplified, modern Russian, her account offers a firsthand glimpse into how a traditional cultural institution continues to […]

Advanced Russian Language Test

Free Online TORFL Practice Test: Reading Comprehension

Free Online TORFL Practice Test: Grammar and Vocabulary

Basic Russian Language Test

The Circus in Russia: Olga’s Blog