Kulebyaka (Кулебяка) is one of Russian cooking’s refined delicacies. It’s also somewhat of a mystery to many, who know of it only from the works of great Russian authors such as Chekhov and Gogol. Chekhov, in “The Siren,” makes the dish sound sensual: «Кулебяка должна быть аппетитная, бесстыдная, во всей своей наготе, чтоб соблазн был.» (“The Kulebyaka should be appetizing, shameless in its nakedness, a temptation to sin.”) Gogol, meanwhile, gives a near-ridiculous recipe that stuffs everything and anything into the dish (see below).

Closely related to the “пирог” (pirog), the kulebyaka is typically known wherever the hand-held stuffed-bread pirog is known. However, the kulebyaka is a much rarer find. The shortages of Soviet times helped to push the richer, more complex кулебяка, known as a food of the aristocracy, off the menu. Inside Russia today, however, traditional Russian cooking from the pre-Soviet era is making a comeback. Thus, the кулебяка is finding its sometimes-sensual, sometimes-near-ridiculous way back onto Russian dinner plates.

How It Earned Its Name

(Почему они носят такое название?)

Pirogi, or pies, are a staple of Russian cuisine. Tasty and filling, the pirog comes with a bready shell that is filled with just about anything – savory or sweet. The word “pirog” comes from an ancient proto-Slavic word “пир” which referred to a feast or festivity, indicating that they were once regarded as a delicacy to be savored on special occasions. Today, however, they are a staple of the Russian diet and can be found in supermarkets, restaurants and cafes, sold by street-side vendors, and are frequently made at home.

Pirogi, or pies, are a staple of Russian cuisine. Tasty and filling, the pirog comes with a bready shell that is filled with just about anything – savory or sweet. The word “pirog” comes from an ancient proto-Slavic word “пир” which referred to a feast or festivity, indicating that they were once regarded as a delicacy to be savored on special occasions. Today, however, they are a staple of the Russian diet and can be found in supermarkets, restaurants and cafes, sold by street-side vendors, and are frequently made at home.

The kulebyaka essentially puts the “пир” back in the “пирог.” Whereas the pirog is generally made to be a self-contained, hand-held unit, the kulebyaka is generally large enough to be cut and shared. Whereas the pirog is often 50% bread to 50% filling, the кулебяка is always dominated by its filling, often with a bread crust just thick enough to prevent the filling from breaking and spilling out of the shell.

The name “kulebyaka” comes from the Russian word “кулебячить,” which means “to knead” or “to sculpt; shape with the hands.” The artistry of the kulebyaka is usually immediately apparent. Whereas the pirog is generally a simple dish, with one ingredient in a simple package, the kulebyaka is complex, often with multiple, layered ingredients in a decidedly large and artful bread shell.

Incidentally, kulebyaka is often rendered in English as “coulibiac.” This is because it was, apparently, first introduced to many English speakers via the many French chefs who were brought to Russia in the 19th century and took the recipe back to France when they departed. The English word is derived from the French rather than the original Russian.

When and How to Eat Kulebyaka

(Как правильно есть кулебяку?)

Although kulebyaka is now making a comeback, it is still very much the delicacy it always has been. One is most likely to find kulebyaka on banquet menus for weddings or corporate parties. One can also find it in a chain of inexpensive Russian restaurants called Shtolle. Shtolle, which has locations across western Russia, hangs historical pictures at all locations to create a somewhat old-time environment remembering tsarist times. It specializes in Russian pies – both pirogi and kulebyaka.

Kulebyaka is nearly always a savory dish. It can be eaten as a main course (as is generally the case at Shtolle), but can also be eaten as side, or served with soup in place of bread. Kulebyaka is served as slices from a usually rectangular but sometimes round loaf.

When served as a main course, the kulebyaka will often have a dipping sauce such as béchamel to accompany. If it is served as a side dish along with soup, it does not require any sauce.

Preparing Kulebyaka

(Как правильно готовить кулебяку?)

The dish of kulebyaka can be made from nearly any savory filling and is always served hot. The most traditional fillings are fish or meat accompanied by such options as buckwheat, mushrooms, eggs, and spices. However, it can be filled with almost anything available. Traditional recipes for kulebyaka tend to make use of more expensive ingredients such as caviar and other delicacies such as those mentioned in Gogol’s description. During the Soviet era, for instance, “капуста” (cabbage) became a common base in the dish when it was still made, replacing the more expensive fish.

In a classic kulebyaka, the fillings will be layered, sometimes even going so far as to separate the layers with a thin “блин” (blin) to keep the flavors from mixing until a full bite melts together in your mouth. These layers are often layered vertically, but can also be side by side, pyramid shaped, or just about in any other arrangement, creating “pockets” of unique flavor. Simpler kulebyaka recipes will mix the filling ingredients together. A common rule is that, no matter what ingredients are used, the quantity of filling should exceed that of the shell by at least 2 to 1.

Kulebyaka often have shells decorated in designs or shaped to resemble an animal such as a fish, pig or even a crocodile.

Let’s Cook!

(Давай приготовим!)

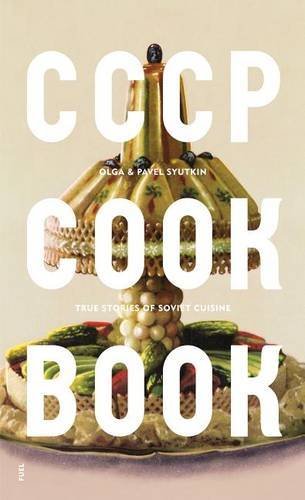

See below for a free recipe for kulebyaka. See also the free videos online. If you are interested in cooking from Russia, Ukraine, Georgia, and other places in Eurasia, make sure to see our other resources! You might also be interested in the following specialized cookbooks we’ve enjoyed:

|

|

|

|

| Кулебяка с лососем | Kulebyaka with Salmon |

| Ингредиенты

Для теста:

Для начинки:

Для грибной начинки:

Для рисовой начинки:

Для блинчиков:

Для соуса бешамель:

Для смазывания теста:

Для подачи:

Приготовление

Сборка кулебяки

|

Ingredients

For the dough:

For the filling:

For the mushroom filling:

For the rice filling:

For the pancakes:

For the béchamel sauce:

For dough glaze:

For the presentation:

Preparation

Assembling the pie

|

Excerpt From Dead Souls,

By Nikolai Gogol

Part 2: Chapter 3

| Оригинал | Translation |

| – Да кулебяку сделай на четыре угла. В один угол положи ты мне щеки осетра да вязигу, в другой запусти гречневой кашицы, да грибочков с лучком, да молок сладких, да мозгов, да ещё чего знаешь там этакого…

– Слушаю-с. Можно будет и так. – Да чтобы с одного боку она, понимаешь – зарумянилась бы, а с другого пусти ее полегче. Да исподку-то, исподку-то, понимаешь, пропеки её так, чтобы рассып’aлась, чтобы всю ее проняло, знаешь, соком, чтобы и не услышал её во рту – как снег бы растаяла. «Чёрт побери! – думал Чичиков, ворочаясь. – Просто не даст спать!» – Да сделай ты мне свиной сычуг. Положи в серёдку кусочек льду, чтобы он взбухнул хорошенько. Да чтобы к осетру обкладка, гарнир-то, гарнир-то чтобы был побогаче! Обложи его раками, да поджаренной маленькой рыбкой, да проложи фаршецом из снеточков, да подбавь мелкой сечки, хренку, да груздочков, да репушки, да морковки, да бобков, да нет ли ещё там какого коренья? |

“Start by dividing the kulebyaka into fourths. Into one of the divisions put the sturgeon’s cheeks and some viaziga (the dried spinal marrow of the sturgeon), and into another division some buckwheat porridge, young mushrooms and onions, sweet milk, calves’ brains, and anything else that you may find suitable. Also, bake it to a nice brown on one side, and but lightly on the other. Yes, and, as to the underside, bake it so that it will be all juicy and flaky, so that it shall not crumble into bits, but melt in the mouth like the softest snow that ever you heard of.” And as he said this Pietukh fairly smacked his lips.

“The devil take him!” muttered Chichikov, thrusting his head beneath the bedclothes to avoid hearing more. “The fellow won’t give one a chance to sleep.” Nevertheless he heard through the blankets: “And garnish the sturgeon with beetroot, smelts, peppered mushrooms, young radishes, carrots, beans, and anything else you like, so as to have plenty of trimmings. Yes, and put a lump of ice into the pig’s bladder, so as to swell it up.” |

Our Favorite Kulebyaka Videos

From a Russian cooking show called “Обед безбрачия” (a play on words from the Russian phrase “обет безбрачия,” which means “vow of celibacy,” with “безбрачия” meaning “without marriage.” Thus, the name of show refers to “lunch without marriage.” The host shows us how to cook a classic, three-layered fish kulebyaka. He comes across as perhaps more than a little sexist as a running assertion in the piece is that the kulebyaka is an “absolutely masculine pie” that “should never be touched by women’s hands.” However, the Russian is spoken slowly with a lot of pauses which helps with comprehension. The cooking steps are clearly shown which should make it easy to follow along at home as well.

Vegetarian kulebyaka! The filling is a single layer with cabbage as the main ingredient. The spoken Russian is fairly simple and clear, but it also has English subtitles.

Anti-vegetarian kulebyaka! A guy with a mohawk makes an extra-meaty kulebyaka. He has something of a strange accent, but is fairly easy to understand.

You Might Also Like

Olga here turns her attention to the modern Russian circus, describing what it is like to attend a contemporary performance, from the atmosphere inside the circus building to the acts that still draw enthusiastic audiences today. Written in simplified, modern Russian, her account offers a firsthand glimpse into how a traditional cultural institution continues to […] Russians have typically gotten nearly three weeks off a year just for holidays. This has changed in recent years and especially since the start of the war in Ukraine, as Russia has pushed for greater effeciency in its economy. While the long New Year holidays remain, most others are now more modest, with often with […] I originally titled this piece “Ghosts of Holidays Past,” way back in 2006. It was an early project I completed for SRAS, written after just three years with the company. Looking back nearly twenty years later, I can see the youthfulness in my writing. While the boundless optimism of that period has been tempered by […] In Russian, New Year is the major celebration of the year. Picture it as Christmas, New Year, and the Fourth of July combined. There are presents, decorated trees, a mythical bearded gift-giver, fireworks, toasts, food, and the grand New Year countdown celebrated at midnight – all associated with this one holiday. Russians are even typically […] Russia and Central Asia offer what can seem to be a bewildering selection of dairy products in their transnational food cultures. An area of special note, and often one of the strangest to Westerners, is the seemingly never-ending assortment of fermented milk drinks and products in the gastronomic repertoire. To cut down on the brow-furrowing […]

The Circus in Russia: Olga’s Blog

Russian Holidays 2026: A Complete Guide

A History of Russian Holiday Ornaments

New Year Holiday Celebrations: Vocabulary and History

The SRAS Guide to Fermented Milk