“Kluski śląskie” (KLOO-skee SHLOWN-skee) are soft, circular-shaped, flattened dumplings made from mashed potatoes and potato flour that typically have an indent in the center. This indent is their distinctive physical characteristic, and acts like a sauce-holder. They are traditionally served with goose, pork roast, gravy, or stew, or with caramelized onions and/or bacon cracklings. They are also a great vegetarian option too, however, when accompanied by mushroom gravy.

They are unlike any other dumplings in Poland due to their appearance and texture. They look mushy and bouncy, are gummy in texture, and are surprisingly addictive. They are also, despite the deceptively short list of ingredients, a bit of challenge to cook.

Why Is It Called Kluski?

(Dlaczego “kluski śląskie” jest tak nazywany?)

“Kluski” (singular: klusek or kluska) means “pasta,” while “śląskie” is the adjectival form of Silesia (Polish: Śląsk), a southwestern region in Poland that includes the major city of Wroclaw. Silesia has centuries of historical ties with nearby Germany, the Czech Republic, and Austria. The culture there is a distinct mix of German, Polish, and Moravian, the Moravians being a West Slavic ethnographic group now located in the Czech Republic.

Silesia thus has its own traditions, folk customs, dialects, art, and cuisine, with “Kluski śląskie” its most famous dish.

There are, in fact, several types of kluski in this region. “Kluski czarne” (black dumplings), also known as “kluski żelazne” (iron dumplings) or “kluski szare” (gray dumplings), are popular in Upper Silesia. These are different from “kluski śląskie” because grated potatoes are added, which gives them a distinct, dark color.

When Do Poles Eat Kluski?

(Kiedy Polacy jedzą kluski śląskie?)

Both black and Silesian kluski are served at weddings and other traditional feasts in the Silesia region, but kluski śląskie are popular across all of Poland. Only in Silesia do they have a recommended time to be eaten — at Sunday dinner.

They should be served in odd numbers, as odd numbers are considered positive in Polish culture. Odd numbers, it is believed, represent the possibility of increase.

Kluski have long been part of Polish culture and even appear in medieval legends and historical records. For instance, in one legend a peasant man named Konrad, who lived in the village Zielony Dąb (now the Dąbie settlement in Wroclaw), faced starvation after his wife Agnieszka died from the plague. Agenieszka had been famous for making the best kluski śląskie in Silesia. One day, Agnieszka appeared in a dream, informing him that she would leave a magic cauldron filled with fresh kluski every night. The only catch was that he had to leave at least one dumpling in the bottom of the cauldron for it to be refilled again the next night. Upon waking up, Konrad saw a cauldron full of kluski, but could not control himself and tried to eat the last dumpling. However, the last dumpling refused to be eaten and ran away. Konrad was chased by the ghost of Agnieszka and turned into a stone at the top of Kluskowa Gate, an archway that connects the 13th century St. Giles Church in Wroclaw with a sixteenth-century Gothic style chapel. The cauldron never filled again.

How Do You Properly Cook Kluski?

(Jak odpowiednio ugotować Kluski śląskie?)

First, be sure to use the right type of potato. You need older and smaller yellow potatoes; if you use potatoes that are too fresh, the dough will not work out. They should be a little soft, but not to the point of being spoiled. Boil the aged potatoes and mash them very well.

The proportion of flour to mashed potatoes is critical. Local chefs will measure this by, in bowl, dividing the mashed potatoes into quarters, removing one quarter, and refilling the hole with the flour. Adding the removed mashed potatoes back in and mixing should give you about the texture you need.

The egg is optional. Some cooks use it, others don’t. I recommend it, though, as it really helps make forming the dough easier.

The dough should be like modelling clay. If it’s too dry, the dumplings will dissolve in the water. If this happens, add a teaspoon of water at a time to moisten it to the right texture. The dough must also not be too moist or the end consistency will be soggy. If they stick to your fingers at all, continue adding potato flour, pinch by pinch to firm it to the right texture.

Texture is most important with kluski. When I made them in Warsaw, we had to add water to moisten them, and then add more potato flour several times until it was the right texture.

When you boil them, use lightly salted water and add them one-by-one to the water until they are all in. You can boil them together, but if you drop them all in at once, they are likely to stick together. They will drop to the bottom of the pot of boiling water initially, but then quickly resurface, and this is when timing is pertinent. They should be boiled for approximately three minutes after resurfacing.

Let’s Cook!

(Gotujmy!)

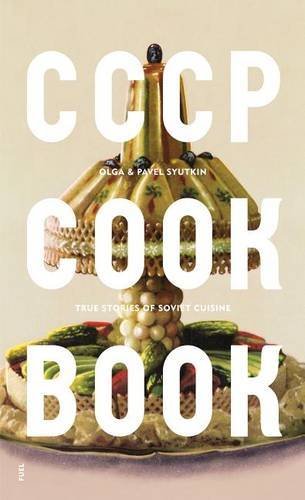

See below for a free recipe for kluski. See also the free videos online. If you are interested in cooking from Russia, Poland, Ukraine, Georgia, and other places in Eurasia, make sure to see our full, free Eurasian Cookbook online! You might also be interested in the following specialized cookbooks we’ve enjoyed:

|

|

|

|

| Kluski Śląskie | Silesian Dumplings |

Składniki:

Przygotowanie:

|

Ingredients

Preparation

|

Our Favorite Kluski Śląskie Videos

This video, in slow, clear Polish, shows how to make kluski step-by-step, including a good example of how to form them and put them in the water.

You Might Also Like

Polish holidays are heavily steeped in Catholic tradtion. They all have a distinctly Polish flair to them, however, in their foods, colors, and celebrations. Note that in Poland nearly everything closes for public holidays! Everyone will be celebrating! Find out more about Polish holidays, their history, cultural significance, and related days off below. Days Off […] What shapes Polish national identity? The answer is complex and personal, but one key element is the Polish national narrative. This includes the heroes and pivotal events taught in schools, the places central to the nation’s collective memory, and the language and beliefs that frame its worldview. A national narrative goes beyond history: it is […] Catholic Mass in Poland is not only a religious ritual but also a reflection of the nation’s history, culture, and identity, shaped by centuries in which Catholicism anchored Polish society through partitions, war, and communism. Today, around one-third of Poles attend Mass weekly and 71% identify as Catholic, making Poland one of Europe’s most religious […] The Talking Phrasebook Series presents useful phrases and words in side-by-side translation and with audio files specifically geared to help students work on listening skills and pronunciation. Each entry below, divided by category, features an English word or phrase in the left column and its Polish translation in the right. In the center column for […] Polish food is hearty, flavorful, and deeply rooted in tradition. It is also experiencing a revival, re-inventing itself in major Polish cities as the country celebrates its heritage and embraces the latest trends and inspirations from world cuisines. Today, while dishes like pierogi, kielbasa, and bigos (hunter’s stew) are one you must try while visiting […]

Polish Holidays 2026: A Complete Guide

Poland’s Story of Identity: Heroes, Memory, and Meaning

Attending Catholic Mass in Poland as an American

The Talking Polish Phrasebook

Dictionary of Polish Food