I’m an anthropologist. Actually, I’m still a year of fieldwork and a dissertation away from getting my Ph.D., so that makes me an anthropologist-in-training. In September 2007, I will move to Central Asia to study the ways people think about things like their ethnic group and their religion, and how that affects their participation in their country’s life. To prepare for that, I visited Kyrgyzstan this summer. The main reason for that trip was to learn some Kyrgyz—I’ll be asking people about their lives, and I want to be able to do that in their language. However, this trip also gave me the chance to observe, firsthand, some everyday situations that will also be part of my study.

Researchers in my field tend to privilege a certain kind of method called “participant observation.” The idea is that you can learn a lot by watching and talking to people, but you can learn even more by watching and talking to them while actually doing what they’re doing. For example, you can look at the yurts that dot the Tien Shan mountains and you can ask the people about the yurts, but in actually building a yurt, you learn things that you would be less likely to learn otherwise, like the relationship between family size and housing which runs something like the following: Many Kyrgyz families have ten or more children. Setting up a yurt involves a delicate balancing act, and it helps to have that many hands to keep it from falling in on you while you’re building it.

I learned more in a few months of participant observation than I did from the dozens of articles and books I’ve read while preparing for my fieldwork. I’ve designed this article as a sort of advice column for someone who wants to get involved in people’s lives and see more of a country than just the restaurants and universities. I’ve organized it into a few sections of general advice I derived from my visits to five of Kyrgyzstan’s seven provinces. I’ve divided those sections into specific suggestions, illustrated by some stories from my own experience.

Bishkek: Plan your Participant Observation

I rented an apartment in Bishkek (in Chui province). This served as a base of operations for studying Kyrgyz and doing my more academic learning about Kyrgyz identity, nationality, and culture. If you’re not Kyrgyz, doing the kinds of things Kyrgyz do takes planning. You have to decide a lot of logistical questions: Where you want to go? What you want to do? Who’s going to take you there? How much will it cost? You don’t want these to surprise you. Also, if you’re withdrawing money from a foreign bank account, you need a trustworthy bank or ATM. Both of those things are rare outside of Bishkek. I’m sure it’s a terrible feeling to be out in the provinces and realize that you don’t have enough money to get home. However, because I set up a home base and planned before I left it, I never experienced that feeling personally.

Suggestion #1: Find a guide.

You can (as an article on Kyrgyzstan in the New York Times recently suggested) go to companies like Community-Based Tourism or Kyrgyz Concept and set up an excursion to a specific part of the country. I advise against it. Those kinds of tours tend to be heavy on the observation, but light on the participation. You can set up an itinerary yourself. You just need a guide. My main guide was my Kyrgyz language teacher, Tynara Ryskulova.* Tynara is a professor of Kyrgyz Studies at the American University – Central Asia. She possesses the two characteristics of a good participant-observation guide: she is nice and she knows people. Tynara was able to introduce me to her family and friends who were doing interesting things, which allowed me to do those things as well. Find someone you can trust. That’s even more important than finding someone you can easily communicate with. AUCA seems like a good source for trustworthy guides: the faculty and students are friendly, usually know English, and are often very willing to take a trip with you.

Suggestion #2: Learn the local language.

I already know Russian fairly well, but the further I got from Bishkek the less that mattered. I had to study Kyrgyz. It would be naïve to think you could spend a few months learning a language and know enough to get along all by yourself. That’s beside the point. Once, I was sitting in a circle of men eating sheep (a much more common occurrence than you would think). I received a dish of broth from the person to my right and held it for the older man to my left to dip his meat in it. He said “chong gishi bol” (may you be a big person.) That’s a compliment older people give to younger people when the younger people do something helpful, and I understood that and said “rakhmat” (thank you.) The fact that I understood just that small bit of Kyrgyz garnered approving looks from the men in the circle. You gain confidence working with people when you know even a little of their language. In turn, they are often more willingly let you participate in their lives. You may need an interpreter the rest of the time, but those few times you don’t will really count.

Suggestion #3: Don’t worry about seeing everything.

I never saw the supposed tomb of the mythical Kyrgyz hero Manas. I never rode a horse up to the black rock where Arstanbap prayed at dawn. I didn’t swim in Issyk Köl. You’re not going to see and do everything because you are not going to have the time or the money or the stamina. Focus on living life with people instead of seeing as many sights as possible. I spent a day making a wool rug (gis) with a family when I could have gone to see all kinds of rivers and mountains and museums and monuments. It was worth it to make the rug and meet the people.

Issyk Köl: Do Things That Make You Uncomfortable

Issyk Köl means “hot lake,” and is the name of the body of water as well as the province that houses it. The lake is salty so it never freezes over, even in the winter, and it has been a popular resort area since Soviet times. I stayed with Tynara’s family in the village of Saruu, on the southern banks of the lake. Our trip was something of a special occasion. Tynara’s father had died four years ago; he was the clan head, so his family has a memorial for him each year. The memorial (referred to as a toi, which is a general word for any special family gathering) involves the sacrifice of a sheep.

Suggestion #4: Get your hands dirty.

All the guests gathered in the yard and a few men (in this case, two of Tynara’s brothers) brought a sheep to the middle of the group. Everyone sat or squatted as the animal’s throat was cut and the blood poured into a basin. An old man in the group recited from the Qu’ran. After the recitation and the sheep’s death-throes were done, everyone stood up and went about making preparations for the meal. I was interested in the actual process of rendering the sheep. Tynarbek, one of the brothers who performed the sacrifice, was kind enough to explain why they did what they did. He also asked me to help him cut open the stomach. As I inserted the knife and had to keep myself from retching at the smell. I’ve taught about pastoralists and animal sacrifices in introductory anthropology classes. But now I know what it feels like to have my hands covered in fat. I’ve seen young sons look on as their fathers went about their work. In a few years, those fathers will give the knife to their sons and teach them the process. This experience is something you can’t learn from a book.

Suggestion #5: Sheep stomach won’t kill you.

Neither will sheep lung. Or horse intestine. I know because I ate all of these things and survived. I’m not saying the innards tasted good. In fact, the horse intestine did make me a little sick (just plain horse meat is very good, however). Your momentary discomfort is worth the rapport you build by eating with people. My hosts boiled most of the meat from the sacrifice for three or four hours before we ate it. The face and hooves, however, got cooked by blowtorch, which took the hair off while it cooked the meat. They cut this meat off the bone, fried up some of the spare fat, and passed it around to the guests as an appetizer.

I had the fortune, as it were, of being near the cooking area when this happened. The men handed me the tray. I looked at the meat, looked at the fat, and decided the meat looked better. Before I could put it in my mouth, they stopped me and said, “No, no. You have to eat it like this, or it won’t taste good,” and demonstrated picking up a piece of meat, a piece of fat, and eating both together. I grabbed what looked like one of the smaller pieces of fat, only to find it attached to three or four other chunks. I was about to shake off those stragglers, when I looked around. They were all nodding their heads approvingly. They were saying “turaa, turraa,” (yes / that’s right). Eating a little sheep fat opened up doors of trust that led to very valuable conversations and experiences later on.

Suggestion #6: The water tastes funny because it’s good for you…

I had a similar experience the second time I went to Issyk Köl. I went on a pilgrimage to Manjili, a holy site that contains a series of springs that are thought to have special powers. Manjili was a holy man who is buried at the site. The first spring we went to had a row of cups lined up next to it. I took a gulp and tasted the sulphur-rich water. The taste worried me, but there was nothing I could do about it. The other springs we went to tasted less like sulphur, and more like dirt. There were special springs for people who had back problems, leg problems, fertility problems, virility problems, and even luck problems. Tynara’s younger brother Tursbek and his wife were with us on this trip. They had empty plastic bottles to fill from various springs. (When we were told the next spring on our visit was the love spring, Tursbek’s wife turned to him and abruptly told him to hand over one of the empty bottles).

Our guide to the springs was considered clairvoyant. At a spring where Manjili and his family supposedly slept, she sat us down, pulled out a string of beads with the 99 names of Allah on them, and proceeded to tell the future. She pulled at the beads for some time, the suddenly stopped, turned to members of our group, and told us something about our lives, or gave us instructions for fixing family problems. It seems that not only will my next trip to Kyrgyzstan be successful, but I will meet a man in a large building, my project will interest him, and he will help me accomplish it. She didn’t know beforehand who I was, what my line of work was, or why I had come to Kyrgyzstan. The people in my group were very impressed. We ended by sleeping for a few hours where Manjili slept. We walked back towards the lake as the sun was setting. I wasn’t thinking about the sulphur water. I was wondering if the luck spring really worked. And, I have to admit, I do get a little nervous now when I walk into large buildings.

Naryn: Work the System

Some people I talked to suggested that Naryn was the most Kyrgyz of all the provinces. Most of the country’s Uzbek population lives south of this province, and the Russians tended to keep to the northern areas. In fact, much of Naryn’s population was nomadic well into the 20th century, and for good reason. It seemed that there wasn’t a single tree in the province that wasn’t planted and irrigated. The soil is just too rocky. While the mountains around Issyk Köl were full of pine and juniper trees, many of the mountains in Naryn were just as green, just as high, but they only had grass on them.

Suggestion #7: Go with the family connections.

Again, Tynara opened up opportunities for me. Her sister teaches school in Kochkor, a town about three hours from Bishkek, just over the border from the Chui province. We stayed with her family our first night. I learned that we would need a guide and chauffer. The infrastructure in Naryn is very poor; there are some places where the roads actually disappear back into the reddish-brown earth. Whole bridges are just not there anymore. We needed not only someone who knew his way around, but also had the means to drive through small streams, if need be.

The next day I met him: Tynara’s sister’s friend’s husband. He had a Niva, which is the Soviet version of an SUV. I’ve driven in a lot of Soviet cars but this is the only kind I’ve seen that has four wheel drive. During our stay in Naryn, I became very grateful for this man. I became even more grateful for his car: we drove places where I thought only a goat could climb. We wouldn’t have been able to make the trip if it wasn’t for our guide, and we found him through the informal system of connections that almost everyone in Kyrgyzstan has. You can call a tourist agency, but finding guides, places to stay, rides, and even good conversation is easier and more efficient through this informal system. It is also less expensive: the closer the guide is to your original contact, the less you’ll have to pay.

Suggestion #8: Stay in a yurt.

While in Naryn province, we visited Son Köl, a very high mountain lake. There are yurt camps there that will give you a meal and lodging for a price. We stopped at a lone yurt to find a woman baking bread, which consisted of spreading the dough in a flat metal pan, covering the pan with a curved metal lid, and then covering the whole thing with flaming dung. Surprisingly, it could be the best bread I’ve ever eaten—served with strawberry preserves and fresh butter. When eating (or doing anything else) in a yurt, we sat on the floor. This one had a table, but in some yurts there was just a mat on the floor. We ate with our hands, just dipping the bread in the preserves or the butter (although most of the more tourist-type yurts have spoons). We didn’t pay anything for this. The owners were related to our guide.

When we visited Issyk Köl for Tynara’s father’s toi, there was not enough room in the house for all the guests. We set up the family yurt behind the house, and I and one of Tynara’s other American students lived there. Yurts aren’t private places. There were a lot of children at this gathering, and they spent most of the time in the yurt with us. The door to a yurt is a wool flap that stays rolled up during daylight hours. No one knocks. You don’t have to say anything when entering. One little girl would walk in, take off her shoes, find an empty spot on the floor, and sit down. Sometimes I talked to her, sometimes I studied, sometimes I took a nap. She would leave after about five minutes, not needing to say goodbye. She usually came back five to ten minutes later with one or eight of her cousins in tow.

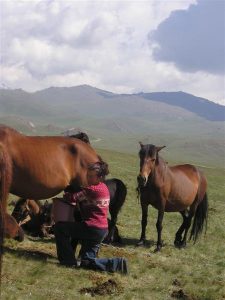

This lack of privacy gave me an opportunity to see people’s everyday lives in Naryn. The family didn’t mind that I watched them while the children did their chores, while they washed the dishes, or while they milked their mares. I have yet to meet a Kyrgyz who doesn’t like kymyz, a drink made from fermented mare’s milk. I had tried kymyz several times by this point—I could hardly avoid it (and it does taste good after the third or fourth time). At Son Köl I got to try kymyz before it becomes kymyz. They milked the mares and simply handed me the bucket. There are no tours that will do that.

Osh: Places Don’t Talk, People Do

The southern city of Osh is built around a large hill called Solomon’s mountain. It’s named after King Solomon, of Qu’ranic (and Biblical) fame. According to tradition, Solomon came to this mountain and prayed. There is a small mosque on the top of the hill, built around five impressions in the rock (supposed to be the imprints of Solomon’s knees, hands, and forehead). The impressions are actually likely the remnants of a Zoroastrian shrine (Zoroastrianism used to be very strong in Kyrgyzstan). A huge museum juts right out of the mountain. I suggest you walk right past it. If you go into the museum, you’ll see some rock-art reproductions, a few interesting Islamic artifacts, and a lot of taxidermy. If you bypass the museum, you can see what makes Solomon’s mountain an important site: the people.

Suggestion #9: You learn more by talking than by looking.

A lot of Kyrgyz told me that people in southern Kyrgyzstan are more religious than people in the north. I don’t know how true that is, but there are certainly more religious sites in the south. There were all kinds of smaller shrine sites on the mountain–caves with supposed spiritual powers (very small and hard to fit into, but the rock is absolutely smooth from centuries of people crawling in), indented rocks that people (of all ages) slid down in order to be healed. There seemed to be as many different perspectives on this as there were people. Many said that the sliding-rock had healing powers. However, one very conservative man I talked to—a Tatar from Novosibirsk, Russia—said that was actually a false belief. He said Allah healed the people if they believe; the rock was just an instrument.

Talking made me wish I hadn’t wasted my time or money on the museum and instead had spent more time with the people. I saw this man accompany his children into the cave and pray with them. Later, at the top of the mountain, he invited me to join his family in prayer. I learned nothing from the museum. I learned everything from the people who came to Solomon’s Mountain, not as tourists, but as believers.

Suggestion #10: Walk (and shop) the bazaar.

Bazaars sell fruit and eggs and laundry detergent and plumbing supplies and meat still hanging on the hook. At the livestock bazaar in Karakol (Issyk Köl province), you get to squeeze through waves of horses, sheep, yaks, cows, and humanity. They sell piglets out of the trunks of their cars.

I especially recommend the bazaar in the center of Osh. In the summer, there are literally mountains of watermelons, sold whole or by the slice. I tasted absolutely fresh figs for the first time in my life. You can hunt for nuts and spices and hear the traders call out to compete for your business (in Kyrgyz, Uzbek, Russian, and sometimes even in English). It might be a little easier, comfortable, or even more sanitary to shop in the Turkish chain-stores in Bishkek but, in my opinion, cashews and raisins taste better when you bargain for the price and then pick them out of the sack yourself.

Jalal-Abad: Be Kind to Strangers.

While traveling through the southern provinces, our car broke down on the way to a mazaar (“holy site”). The car overheated, and our driver went down to a nearby farm to ask for water for the radiator. We could hear talking and laughing, and a few minutes later he came back. We couldn’t see his water canister. When we asked him where it was, he said, “It’s down there. We’re staying here tonight.” We walked to the farmhouse as he drove the car down a small path into the nearby fields. Six men came from the house, greeted us, opened the hood of the car, and began a very animated conversation about what was wrong and who could fix it.

We went to the farm. The family sat us down, fed us (we had to stop them from killing a chicken—we weren’t that hungry), told us where the spring was so we could wash, laid out bedding in the yard next to the donkey and chickens, hung our belongings in a tree, and wished us well when we left the next morning. They didn’t ask our names, didn’t ask where we came from, and didn’t ask for payment. And they fixed our car.

This is normal for rural Kyrgyzstan. Traditionally, you don’t need to knock at a yurt when you approach it. As I walked around the farm yard at sunset, I could see mountains in the distance that looked three distinct shades of blue. I’m not even sure what color the sunset was. All I could hear were a few animals, children completing their chores, and the adults laughing in the house as they finished their day. I think it was one of the more beautiful things I’ve ever seen in my life.

I couldn’t have planned that if I tried.

This is the first of a two-part series. Read part two here

*Note: Tynara Ryskulova works with SRAS students studying Kyrgyz language and culture.