Russian has many ways of expressing affection and describing the various phases of falling in love and establishing a relationship. This bilingual resource is meant to build your vocabulary by providing Russian phrases within English text. It covers everything from meeting to dating and marriage and in multiple styles from slang to classical literary prose.

Dating – Свидание

If a man likes a woman, he can ask of her “давай встретимся” (“let’s meet”) or, if he is more bashful, he could say “Я хотел бы с тобой встретиться” (“I would like to meet with you”), and she will understand that he is asking her on a date. This is the perfective form of the verb and involves a single meeting. However, especially if the two already somewhat know each other, the offer might be presented with the imperfective, which immediately presupposes multiple meetings over time. “Давай встречаться” (“let’s date”) or “Я хотел бы с тобой встречаться” (“I would like to date you”), which would imply that the man is looking for more of a relationship.

If she agrees to пойти на свидание (to go on a date), the date might consist of, as is common in America, ужин и кино (dinner and a movie). However, in Russian-speaking cultures, the couple is just as likely пойти на свидание на концерт или в театр (to go on a date to a concert or to the theater). If the couple does go somewhere that costs something, it will always be expected that за все платит мужчина (the man will pay for everything).

Most commonly, however, couples will simply гуляют и разговаривают друг с другом (go for a walk and talk to each other). It is sometimes said of young couples in Moscow that если они могут пройти все Садовое кольцо за одно свидание, то, скорее всего, они влюблены друг в друга (if they can walk the entire Garden Ring in a single date, they are likely in love with each other). The Garden Ring is a series of mostly leafy streets that run about 9.5 miles around the center of Moscow.

On a date, and especially on a first date, men will typically подарить букет цветов/цветок (give a bouquet of flowers/a flower).

Expressing Love – Выражение любви

When they meet, the boy might pay the girl compliments by saying “Ты очаровательна” (“You are charming/enchanting”) or, if he wanted to seem more “hip” and modern, he could say “Ты классная” (“You are first-class/cool”). If, over time, he develops stronger feelings, he might tell her that “Ты мне очень сильно нравишься” (“I like you very much”) or, if he wanted to use another common but less direct phrase, he might say that “Мне с тобой хорошо” (“It is pleasant to be with you”). Of course, if he wants to get right to the point, he would say “Я в тебя влюбился” (“I have fallen in love with you”).

To describe his feelings to his friends using slang, he might say “Я влюбился с первого взгляда” (“I fell in love at first sight”), “Это любовь” (“It’s love”), or he might use the older and more colorful “Я по уши влюбился” (“I’ve fallen in love up to my ears”).

If the woman likes him as well, she might begin “строить глазки” (“to make eyes”), “флиртовать” (“to flirt”) and say “Я скучаю по тебе” (“I miss you”) when he calls her. He might respond and say “Я думаю о тебе” (“I am thinking about you”) or even “Я тебя обожаю” (“I adore/worship you”).

Russian lovers don’t call each other “honey” and often think it amusing when English speakers do. They most often use the adjectives дорогой or дорогая (“dear”), and милый or милая (“sweetie”). Sometimes they will call each other by animal names such as зая (зайчик, зайка) (slang from the word “hare (little hare)”) “котик/котёнок” (“little cat”), or even “рыбка” (“little fish”). In the most modern slang, young people have taken to calling each other “краш” – from the English “crush.”

The most timeless names are tied to long-standing values and symbols in Russian culture. Sometimes lovers will call each other “sun,” a symbol with strong positive connotations in Russian folklore: “солнце” (“sun”) or “солнышко” (“little sun”). A particularly interesting name is “родная” (“my own”), which comes from the same stem as “родина” (“homeland”) and “родственник” (“relative”), two of the highest valued elements in traditional Russian culture. “Родная” can perhaps best be thought of as “soulmate” in English – indicating a very strong and very close bond between two people.

Love in Literature – Любовь в литературе

Probably no one is more famous for sweet nothings in Russian than A.C. Pushkin. His best-known diatribe on love starts as follows: “Я помню чудное мгновение: / Передо мной явилась ты, / Как мимолетное видение, / Как гений чистой красоты.” (“I remember the many miracles / as you appeared before me / Like a fleeting vision, / Like a marvel of pure splendor”). Many of Pushkin’s poems juxtapose love and sorrow. Take, for example, “Унынья моего / Ничто не мучит, не тревожит, / И сердце вновь горит и любит – оттого, / Что не любить оно не может” (“My despondence / Knows no grief nor even sorrow / For again my heart burns and loves, as / The heart cannot not love”).

Dostoevsky, especially later in his career, tended to strongly equate love and suffering. For instance, in The Brothers Karamazov, he writes that “Ад – это страдание от неспособности любить” (“Hell is the suffering of being unable to love”) and in Notes from the Underground, he is even darker, writing that “Любить – это страдать, иначе не может быть любви.” (To love is to suffer and there can be no love without). However, he is also credited with the much more peaceful “Любить человека — значит, видеть его таким, каким его замыслил Бог” (To love a person is to see them as God conceived them).

Along a similar line, Leo Tolstoy writes in War and Peace that “Не красота заставляет нас любить, а любовь заставляет видеть красоту.” (“It is not beauty that makes us love, but that love makes us see beauty.”)

Boris Pasternak also wrote of loving someone unconditionally and dispite (and perhaps even because of) their faults in Dr. Zhivago. The passage reads: “Я думаю, я не любил бы тебя так сильно, если бы тебе не на что было жаловаться и не о чем сожалеть. Я не люблю правых, не падавших, не оступавшихся. Их добродетель мертва и малоценна. Красота жизни не открывалась им.” (“I don’t think I could love you so much if you had nothing to complain of and nothing to regret. I don’t like people who have never fallen or stumbled. Their virtue is lifeless and of little value. Life hasn’t revealed its beauty to them.”)

And if you ever meet someone who doubts in love, Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Magarita offers some very dark advice: “Кто сказал тебе, что нет на свете настоящей, верной, вечной любви? Да отрежут лгуну его гнусный язык!” (“Who told you that this world holds no true, faithful, and eternal love? Cut out that liar’s vile tongue!”)

Marriage – Брак

The man might decide one day to tell the woman “Жить без тебя не могу” (“I can’t live without you”) or “Я люблю тебя больше всего на свете” (“I love you more than anything in the world”). He might simply say “Ты мне нужна” (“I need you”) and she will understand that he feels that he needs her in his life always.

At this time, the man might decide that it is time to “сделать предложение” (“to propose”). He might say, usually after describing his feelings, “Выходи за меня замуж” (“marry me”) or he might use “Будь моей женой” (“be my wife”), which is more common and pithier.

For a bit more on Russian weddings, click here!

Later on, if their family is happy, people can say about them “Они живут душа в душу” (“they live soul-in-soul”), meaning that they live in perfect harmony, that they are soul mates. People may also say simply “У них счастливая семья” (“they have a happy family”). He might call her by more mature terms of endearment such as “моя половинка” (“my (other) half”) or “родная” (“soul mate”). She can call him “моя опора” (“my support, my rock”) and feel protected, “как за каменной стеной” (“like behind a stone wall”). meaning that she can rely on him for anything.

There is also the very interesting and commonly used proverb “Муж и жена – одна сатана” (“the husband and wife are the same Devil”). This means that the two often share and know each other’s thoughts and plans without even communicating them first because they know each other so well and are so similar.

Although some Russians are beginning to see gender roles as a thing of the past, most Russians believe that the ideal home is one in which the wife “обеспечивает хороший тыл” (“provides a solid home front”), to which the man will be the “кормилец и добытчик в семье” (“breadwinner”) who will always “летит домой как на крыльях” (“fly home as if on wings”).

You’ll Also Love

Kupala: Ancient Slavic Midsummer Mythology and its Modern Celebration

Kupala is an ancient Slavic holiday celebrating the summer solstice, or midsummer. Once part of a series of annual rituals, it marked and was believed to sustain agricultural cycles—essential to early human survival. Held as vitally important, these pagan traditions remained deeply rooted even after Christianization, technological change, and centuries of oppression tried to dislodge […]

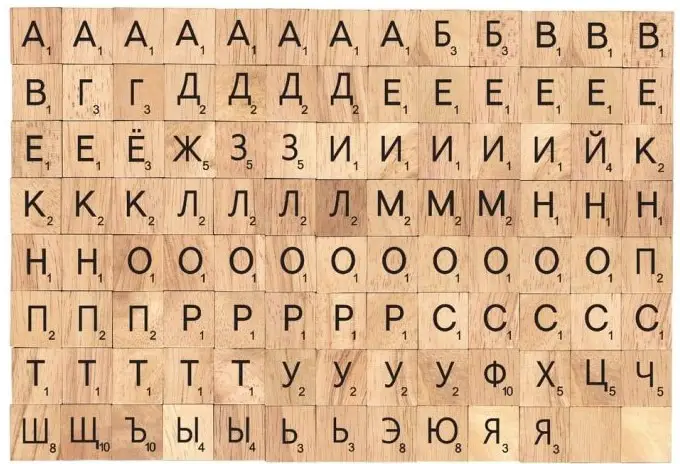

Resources for Students of Russian

This extensive list of web resources to assist students learning the Russian language was developed by SRAS and is now hosted on Folkways, part of the SRAS Family of Sites! Disclosure: Some of the links below are affiliate links. This means that, at zero cost to you, we will earn an affiliate commission if you […]

Haircuts and Hairstyles in Russian – A Vocabulary Lesson

Living abroad brings new challenges to even the simplest tasks, from buying a belt to getting a haircut. When we are presented with a language barrier, an extra layer of uncertainty is added to what would otherwise be straightforward routines. However, knowing a few key phrases and understanding basic cultural expectations can make these experiences […]

Russian Vocabulary: Haunted Places in Russia

Russian folklore is rich with stories of spirits, haunted places, and supernatural forces that influence daily life. These beliefs shape how certain locations, from uncivilized wilderness to abandoned homes, are viewed in the collective imagination. Unclean spirits, or нечистая сила, are believed to settle in ominous spaces like crossroads, swamps, and even ordinary houses if […]

Halloween as a Case Study for Cultural Understanding

Halloween is seen around the world as an American holiday. While it has gained more global popularity in recent years, it is still really only celebrated in the US, the UK, and Canada. In most other countries, including most Slavic countries, it is regarded at most as a reason to host costume parties or perhaps […]