Olga here turns her attention to the modern Russian circus, describing what it is like to attend a contemporary performance, from the atmosphere inside the circus building to the acts that still draw enthusiastic audiences today. Written in simplified, modern Russian, her account offers a firsthand glimpse into how a traditional cultural institution continues to adapt and thrive in everyday Russian life.

This resource is part of a series of free Russian lessons sponsored by SRAS called Olga’s Blog, a series of intermediate Russian lessons focused on culture. The blog documents – in simplified, modern Russian – Olga’s experience finishing high school, starting college, and living life in Moscow in 2006-2007. The text (including the prices given), links, and format of this resource were last updated in 2025.

Briefly on Circus Traditions and History in Russia

Russia has always had strong performing arts traditions. While its achievements in theater, ballet, opera, and concert performance are well-known, Russia also excels in lesser-known performative traditions such as puppet theatre and circus.

In medieval times, itinerant performers such as skomorokhi entertained crowds in with acrobatics, juggling, and comic routines that sometimes involved trained animals. Under Peter the Great, early modern circuses from France and Italy were invited to perform in Russia with equestrian acts, acrobats, and other attractions. The Ciniselli Circus in Saint Petersburg opened in 1877 as Russia’s first permanent brick-and-mortar circus, and other permanent tents and arenas followed across the empire.

After the revolution, theater in all forms became a major venue for communist propaganda and education. Lenin nationalized all circuses in 1919 by decree and the art form was used to promote the “The Soviet Man,” who would be stronger, more disciplined, and capable of astonishing feats due to the effects of Communism. The state invested in training and infrastructure, establishing professional schools such as the Moscow State College for Circus and Variety Arts. In 1936, circuses were placed under the centralized control of SoyuzGosTsirk. After 1991, the centralized circus system evolved into the Russian State Circus Company (Rosgoscirk), which continues to oversee most circus enterprises in the Russian Federation.

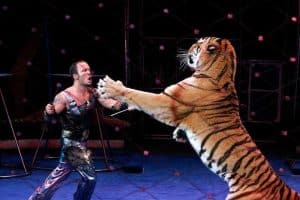

In the modern era, debates have risen about the treatment of trained animals. Many European governments have banned trained animal shows, but they remain common in Russia. Proponents insist that the animals are treated humanely, although some well-published exposes have shown at least individual cases where abuse has occurred. Russia passed the Law on Responsible Treatment of Animals in 2018, which outlawed petting zoos, animal-themed cafes, and placed new regulations on circuses. In 2019, the town of Magas in the Republic of Ingushetia became the first jurisdiction in Russia to ban circuses featuring animals.

Circus performances of all kinds, however, remain a popular form of entertainment in Russia. This is particularly true around school holidays and the long New Year break, when circuses often host special holiday-themed performances and events. The experience Olga describes below can still be experienced across Russia.

Attending a Russian Circus: Simplified Russian Text from Olga’s Blog

This is a lesson from Olga’s Blog, a series of intermediate Russian lessons.

Note that:

- All of the bold words and phrases have annotation below.

- Red words and phrases indicate the subject of this blog entry’s grammar lesson.

- *Asterisks indicate slang.

Привет всем! Наступили долгожданные каникулы. Чем заняться, куда пойти? Конечно же в московский цирк! Здесь можно весело провести время – посмеяться, посмотреть удивительные номера, поесть мороженого и сахарной ваты, сфотографироваться с клоунами и животными в вестибюле перед началом представления! Все вместе это создает особенное, ни с чем не сравнимое удовольствие. Я со своими друзьями часто бываю в цирке.

Здание самого большого в мире цирка находится через дорогу от студенческого городка Московского государственного университета. Большой Московский Государственный цирк на проспекте Вернадского открылся в тысяча девятьсот семьдесят первом году, и он может вместить в своем огромном здании под бетонным куполом три тысячи четыреста человек.

Этот цирк имеет уникальные технические возможности. В нем на глубине 18 метров находятся пять сменных манежей: конный, иллюзионный (который имеет оборудование для фокусов), ледовый, водный и световой (со специальным осветительным оборудованием для шоу). Манежи сменяются за несколько минут.

Есть в цирке и шестой, отдельный манеж – репетиционный. Здесь идет подготовка новых номеров. В репетиционном манеже есть специальные ковры и маты, чтобы защитить артистов от травм.

Но самый известный цирк в Москве – это Московский цирк Никулина на Цветном бульваре. Ему больше ста лет. Это источник веселья и хорошего настроения.

Долгие годы Московский цирк на Цветном бульваре возглавлял Юрий Никулин, выдающийся клоун, актер, знаменитый на всю страну и необыкновенно добрый человек, участник второй мировой войны. Все в России любят его и помнят. Возле входа в цирк Вы увидите памятник этому артисту.

Праздник начинается еще до представления. У входа в цирк можно покататься на лошади, которая будет участвовать в представлении. Внутри радостными улыбками Вас встречают клоуны, у которых можно купить сладости, светящиеся игрушки и воздушные шарики, из которых они делают фигурки животных. В фойе все фотографируются со слонами, обезьянами, тиграми и даже крокодилами!

Программы тут всегда разные и очень интересные. Первым обычно выходит клоун с большим поролоновым носом малинового цвета и показывает смешные фокусы. Потом под купол цирка взлетают акробаты на качелях, ходят канатоходцы* по тонким, как паутина канатам и гимнасты показывают невероятную гибкость и ловкость. А каких только животных не встретишь в цирке! Лошади и слоны, обезьяны и собачки, даже маленькие ежики – все поражают зрителей своим умением делать что-то необычное и веселое.

В других странах цирк не так популярен, как в России, и поэтому иностранцы, впервые увидев цирк в Москве, бывают шокированы и думают, что с цирковыми животными плохо обращаются. Но директор Московского цирка Никулина на Цветном бульваре Максим Никулин говорит, что в цирке контролируют, как артисты обращаются с животными, и «если станет известно, что дрессировщик мучает своих подопечных, его просто лишат права выступать и отберут животных».

Смотришь и не веришь своим глазам – как животные могут творить такие чудеса! И это далеко не все. Когда приходишь в цирк, никогда не знаешь, чем здесь удивят тебя в этот раз.

Vocabulary and Cultural Annotations

Посмотреть удивительные номера: Watch amazing numbers. As in English, “номер” refers to a short performance.

Сахарная вата: Cotton candy.

Здание самого большого в мире цирка: The building of the largest circus in the world. It should be noted that this is the largest circus in terms of permanent seating capacity. Circus Circus in Las Vegas has a larger performance area, for example, and Cirque du Soleil is larger in terms of employees.

Студенческий городок: Campus. This is sometimes translated as “student quarter,” which in this case may actually be a better translation as “quarter” is usually used to refer to a large section of a city. The MGU campus hosts more than 47,000 students, 30 faculties, and 15 research centers, making it a fair-sized city by itself.

Пять сменных манежей: Five changeable arenas. Note that “манеж,” a word Russian borrowed from the French, can also mean “riding school” or “riding hall,” referring to an indoor facility for equestrian activities. There is also a museum in central Moscow, located just outside Red Square, called “Mанеж,” so named because cavalry horses used to be kept and trained there.

Оборудование для фокусов: Equipment for (magic) tricks.

Осветительное оборудование для шоу: Lighting equipment for shows.

Манежи сменяются за несколько минут: The arenas change out in a few minutes. Note, however, that the reflexive is used in this sentence: “сменяются” implying that the arenas change themselves. They are mechanized to do so.

Отдельный манеж – репетиционный: A separate rehearsal arena. Note the use of the hyphenated sentence structure to emphasizes that this is yet another type of arena.

Специальные ковры и маты, чтобы защитить артистов от травм: Special carpets and mats to protect the artists from injury.

Светящиеся игрушки: Light toys. These are the type of lighted, flashing bracelets and luminescent rods sold at Halloween, for mardi gras and for raves in the US.

Фойе: Foyer. Note that both the English and the Russian word are derived from the French word “foyer.” Russian seems to have kept the French pronunciation while English has preserved its spelling.

Большой поролоновый нос малинового цвета: A large, foam rubber nose the color of raspberries.

Канатоходец: Tightrope walker. Note that the word is a compound noun from “канат” (rope, cable) and “ходить” (to walk). See the grammar section of Olga’s Blog_9.1 for more information on forming names of professions.

По тонким, как паутина канатам: On cables thin like cob webs. The Russian, like the English translation we have given it, is poetically structured. While it may not be immediately understandable to a non-native speaker, a major clue to understanding the phrase can be found in noting that “тонким” and “канатам” are both in the dative case and thus are directly connected. “Как паутина” is in the nominative case, indicating that is a separate clause which, in this case, modifies the word “тонким.”

Ежик: Hedgehog. There is a popular Russian cartoon from 1979 called “Ежик в тумане” which cemented the hedgehog’s place in Russian popular culture. Episodes of this cartoon can be seen on YouTube.

Максим Никулин: Maxim Nikulin. You might notice that the last name is the same as the person for whom the circus is named after. Maxim Nikulin is Yuri Nikulin’s son.

Если станет известно, что дрессировщик мучает своих подопечных: If it becomes known that a trainer is maltreating his charge.

Его просто лишат права выступать и отберут животных. He is stripped of the right to perform and the animals are taken away (from him).

Grammar Focus: Figurative uses of non-prefixed verbs of motion

Like English, Russian often uses verbs of motion figuratively. For example, in this edition of Olga’s Blog, Olga uses the phrase “идет подготовка новых номеров” (new numbers are being prepared), using the verb “идти” to indicate a process in motion.

Phrases that used “идти” and “ходить” are most often standard collocations. The verbs cannot, in most cases, be interchanged. Take, for example, the often used phrase “идет снег” (it is snowing). Because snow only moves in one general direction – from the sky to the ground – the phrase “ходит снег,” sounds strange to many Russians, as it seems to imply that the snow is falling to earth, than retuning to the clouds to fall again. The phrase “ходит снег,” is sometimes encountered, though usually in poetic contexts.

Some other instances of one-directional process that usually only use “идти” are listed below:

Идет дождь/град: It is raining/hailing

Идет фильм: The movie is playing

Время/жизнь/работа идет: Time/life/work goes on.

Another, less obvious case is where “идти” is “свитер тебе идет” (the sweater suits you). However, again, this seems logical as the sweater is not likely to suit you, then not suit you, then suit you again.

“Ходить” is much the same way. If it is used figuratively, it often cannot be interchanged with “идти” and retain its figurative meaning. For example, “ходить вокруг да около” (to avoid the point; to talk in circles) describes a convoluted process and thus uses only the imperfective verb. Ходят слухи (rumors circulate) is also often convoluted. Rumors can stop and resurface and they can change in the process of their circulation.

“Ходить за больным” (to look after a sick person), describes a process that is often multifaceted and is a long enough that it can stop and start on several occasions. “Идти за больным” would imply that the sick person is actually being followed.

Some cases can be interchanged, though the meaning will change. “Ходить в джинсах” means “to wear jeans (often)” while “идти в джинсах” would mean “to wear jeans (to a specific place).” Another case is идти по пятам (to follow some one very closely; literally: to follow on some one’s heels) and “ходить по пятам” (to follow some one very closely to and fro).

Another example of a verb of motion being used figuratively is “ездить на нем” (to take advantage of him; literally: to ride him). “Бежать” and “лететь” are often used to describe very fast processes. For example, “время бежит” is equivalent to the English phrase “time flies.””Жизнь бежит” could be rendered as “life flies by” in English. “Слезы бегут” describes tears pouring down some one’s face. “Деньги летят” refers to money being spent very quickly, or that money can easily be spent very quickly.

Examples from Literature

Без дождика люди не могут жить, а дождь идет вниз на землю, а не вверх на луну. A. Chekhov.

А ночь летит тихо и плавно, как на крыльях. I. Turgenev.

Ты, как я вижу, книжный человек, и незачем тебе, одинокому, ходить в нищей одежде без пристанища. M. Bulgakov.

More Free Russian Lessons From Olga’s Blog

The Circus in Russia: Olga’s Blog

Olga here turns her attention to the modern Russian circus, describing what it is like to attend a contemporary performance, from the atmosphere inside the circus building to the acts that still draw enthusiastic audiences today. Written in simplified, modern Russian, her account offers a firsthand glimpse into how a traditional cultural institution continues to […]

The Language and History of Caviar: Olga’s Blog

Olga below describes the place of caviar in Russian food culture. In simplified Russian, she describes where the delicacy is harvested from, the major types of caviar, and how the types differ in cost and quality. We also provide an English primer below discussing more of the history of caviar, how it is eaten and […]

Mushrooms in Cultures and Cuisines: Olga’s Blog

Olga below continues her discussion of the deeply held place that mushrooms have in Russian culture. In part one of this discussion, she focused on how and where and find the mushrooms. In part two, below, she discusses how the mushrooms are preserved, prepared, and consumed. A staple of the regional diet for centuries, mushrooms […]

Mushroom Season Has Begun! Olga’s Blog

Olga below discusses the deeply held national tradition of mushroom gathering. An important part of Russian food tradition for many centuries, Russian children are taught in school from an early age to tell the difference between various types of native mushrooms. Many, like Olga, will go with relatives and friends to the woods to put […]

Study Abroad in America for Russians: Olga’s Blog

As part of her major program in international relations at Moscow State University, Olga applied to study abroad in the United States in 2007. As was not uncommon for students applying for study abroad in either direction, Olga hit several bureaucratic snags. What is perhaps most remarkable about the below text, however, is the description […]