What shapes Polish national identity? The answer is complex and personal, but one key element is the Polish national narrative. This includes the heroes and pivotal events taught in schools, the places central to the nation’s collective memory, and the language and beliefs that frame its worldview.

A national narrative goes beyond history: it is the people, events, places, and values that define how a nation understands itself. It lives in literature, film, and art, in monuments and place names, and in the calls to action used by leaders and activists.

This resource presents Poland’s national narrative in a concise, accessible way to help outsiders, such as tourists, students, and diplomats, grasp the cultural foundations of Polish society and better understand the Polish nation.

Special Themes in Polish Identity

98% of Poland’s population identifies as ethnically Polish, making it one of the most ethnically homogeneous countries in Europe. 71% of Poles identify as Catholic, making it one of the most religious countries in the EU.

Polish language is generally regarded as more important than genetic ancestry for determining “Polishness” for many Poles. Over centuries of foreign occupation, preserving the Polish language and culture became an act of resistance, preserving Poles as a nation, and it remains deeply embedded in the national consciousness. Poland promotes Polish internationally through the state-funded Polish Institutes and Adam Mickiewicz Institute. Among the diaspora, preserving the Polish language, particularly in children raised outside of Poland, is seen as an important yet often challenging task.

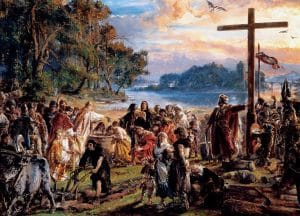

Catholicism is historically and culturally central to Polish identity. The 966 baptism of Polish ruler Mieszko I is seen as the symbolic founding of the Polish state. Poland’s Golden Age began when Lithuania’s grand duke converted to Catholicism to marry the Polish queen, uniting their lands into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which then established itself as Europe’s defender of Christianity against Islamic Ottoman and pagan Mongol threats. Catholicism later distinguished and united Poles under various occupiers under the Partitions of Poland, the Nazi invasions, and Communism, with the Church playing a major role in the eventual recovery of independence. As of 2021, 71% of Poles identified as Catholic, down from 84% a decade before, with most of the drop occurring among Polish youth and liberals as the Catholic Church in Poland has aligned itself with the Polish conservative party. Catholic traditions have deep historical and social roots and dominate the modern holiday calendar, both in Poland and among the diaspora.

Golden Liberty emerged in the 16th century as a system that granted equal rights to all nobles, regardless of ethnicity or religion, and made the king subject to elections and recall by the nobility. Though limited to nobles, Golden Liberty helped usher in a Golden Age for the Commonwealth. Today it is widely seen as the foundation for Poland’s civil rights, individual freedoms, and democratic traditions as reflected in Poland’s early adoption of constitutional government (in 1791, just after the US, and making Poland the second country worldwide to do so) to its early adoptions of equal rights for women, first given in 1918, before the US.

The “Christ of Nations” mythos emerged in the 19th century, when Romantic writers like Adam Mickiewicz likened Poland’s suffering under the partitions to Christ’s crucifixion, with eventual resurrection promised. This vision also cast Poland’s struggles with foreign rule, uprisings, and wars as a moral sacrifice made for Europe’s freedom. The metaphor still shapes culture and even foreign policy, as Poles often view their role as defending not only their own liberty but that of others. It also informs Poland’s stoic fortitude and dry, self-deprecating humor, serving as a cultural lens emphasizing tragedy, irony, and endurance in Poland’s national character.

Polish cuisine is central to national identity, seen as reflective of both Polish history and culture. This is especially true in the diaspora, where food and language are often primary ties to heritage. Iconic staples like pierogi, kielbasa, and stuffed cabbage remain sacred, yet Polish cooking has always adapted with its turbulent history, absorbing new flavors and techniques. Today, Warsaw’s dining scene offers playful pierogi varieties, Polish-Asian fusion, and vegan takes on classics, alongside the traditional dishes that evoke grandmothers and childhood.

Polish literature became a vital vehicle of national identity during the Romantic era, when Poland was erased from the map. Great works from this time urged Poles to remember their Poland as a strong country, celebrate their language and culture, and to remain united. Some works are even credited with inspiring uprisings against occupying powers. Poles remain deeply interested in Polish prose and poetry, including sung poetry, which played a role in Polish resistance to communism.

The Polonaise is a quintessential Polish national dance, traditionally opening balls and still performed today at solemn occasions such as proms and major cultural events. It is marked by graceful, dignified movements, set to a two-part song in ¾ meter with a slow tempo. Having originated from folk dances with hop-like steps in the 17th century, then spread to noble courts.

Geography in Polish Culture

Poland is a large Central European state on the North European Plain, bordered by the Baltic Sea to the north and mountains to the south. Its flat terrain and major rivers, including the Vistula and Oder, have long facilitated trade and cultural exchange. The same openness, however, has left Poland vulnerable to repeated invasions and shifting borders throughout its history.

Warsaw has been the capital of Poland since 1596, when King Sigismund III Vasa moved his court from Krakow. The new location along the Vistula River was chosen as a new capital for the Commonwealth because of its central location between the two older capitals of Vilnius and Krakow. A center for Polish resistance in WWII, it was the site of daring uprisings. Today, it is known as a resurrected city, nearly completely destroyed in WWII and painstakingly rebuilt from its own ruins. Roughly 1.86 million, or 10% of all Polish citizens, live here and 15% of Poland’s GDP is generated in Warsaw. The seat of nearly all major political institutions, it is Poland’s political center and major economic engine.

The Vistula River, Poland’s longest, has shaped its history, economy, and culture. Linking both Warsaw and Kraków to the Baltic Sea, it was central to the Amber Road and later grain exports, connecting eastern Poland to Europe and the world. Long celebrated in paintings and songs as a symbol of beauty and unity, it also served under communism for hydropower, industry, and irrigation. Today, pollution, damming, and proposed infrastructure projects are a focus for Polish environmental movements seeking to preserve the Vistula’s image and ecology.

Tricity consists of three cities along the Gulf of Gdansk. Gdańsk, historically important since the 900s, is a major seaport at the mouth of the Martwa Wisła, a branch of the Vistula River. Once the largest city of the Hanseatic League, Gdańsk—also known as Danzig under its periods of German rule—reflects its contested history in German-influenced architecture. The city was the first target attacked by the Nazis, marking the start of WWII. Later, under communism, it was the center of decisive worker protests that eventually led to the foundation of the Solidarity movement. Sopot, a vacation town with beautiful beaches, and Gdynia, a modern port which grew from a small fishing village in the 20th century, round out the tricity. The area is thus renowned as a popular vacation destination, while its shipyards remain vital for commerce and defense.

Kraków, one of Poland’s oldest and largest cities, was the powerful political, cultural, educational, and economic capital of the Kingdom of Poland and early seat of the Jagiellonian dynasty. Unlike most major Polish cities, it largely survived both World Wars, preserving its original architectural heritage. In 1978, its medieval Old Town became one of the earliest named UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Jagiellonian University, based in Krakow, is one of the world’s oldest and remains prestigious. Kraków has several colleges and universities with a combined 200,000+ students, fostering a vibrant youth culture that fuels nightlife as well as numerous annual festivals and concerts.

The Bieszczady Mountains in Poland’s remote southeast symbolize freedom and solitude. Ancient folklore about them tells of giants, demons, and spirits that roam their wooded nature. They were once the homeland of the Boykos, who were exiled by the Communists after WWII, and the land was left to return entirely to nature. In the 1980s they inspired tales of the “Free Republic of Bieszczady,” a haven for wanderers and artists to escape the Communist authorities. Today, as part of the UNESCO East Carpathian Biosphere Reserve, managed jointly with Slovakia and Ukraine, they protect rare species like bison, wolves, and lynx. These mountains are perhaps the most prominent examples of mysterious, wild, and free natural places, often located at Poland’s peripheries, that are celebrated in art, poetry, and song. Others include the ancient Białowieża Forest, the Tatra Mountains, and more.

National Heroes of Poland

The following people have played pivotal roles in Polish history. Many of the below have monuments to them and places named for them in Poland. They generally appear as heroes in textbook histories of Poland in Polish schools.

Casimir III is the only Polish king known as “The Great.” Rebuilding the country in the 14th century after years of war, Casimir reformed the judiciary, codified laws, and granted privileges to towns and Jews, stimulating economic, cultural, and population growth. He reformed the army and more than doubled Poland’s territory, expanding eastward into what is now Ukraine. His vast construction programs included fortifying cities and founding the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, a major and early center of learning. He is held up today as a model of a wise, just, and highly effective ruler. His transformation of Poland is still recalled in the well-known rhyme that he “found Poland made of wood and left it made of brick.”

The Jagiellonian Dynasty ruled Poland from 1386–1572, marking Poland’s golden age that saw territorial expansion, economic prosperity, and progressive political reforms. Kings like Władysław II Jagiełło, victor at Grunwald in 1410, and Casimir IV, who expanded Poland’s territory, are central to national pride. Sigismund I the Old fostered Renaissance culture. Sigismund II Augustus joined Polish and Lithuanian lands to form what would become the Commonwealth. Meanwhile Queen Jadwiga, canonized in 1997, symbolizes piety and charity. Their legacy is celebrated most in Kraków’s Wawel Castle, where many are buried, and in the prestigious Jagiellonian University, which they founded in 1400.

Nicolaus Copernicus was born in Royal Prussia, then part of the Polish Crown. His 16th-century heliocentric model of the solar system challenged centuries of accepted belief, making him a figure of intellectual courage and innovation. He also made advances in economics. Today, he is celebrated in monuments, museums, and Poland’s currency.

John III Sobieski, Poland’s elected king from 1674–1696, led the 1683 Battle of Vienna, credited with stopping the Ottoman advance into Europe. His image today embodies courage, military genius, and the defense of Christian and European civilization. His love letters to his wife, Queen Marie Casimire, have also added to his image as both warrior and humanist.

Adam Mickiewicz is one of the greatest Polish-language poets and was a leading figure of 19th-century Polish Romanticism. His works, including his most famous, Pan Tadeusz, fueled national identity and inspired several uprisings against foreign rule. He also supported several intellectual movements advancing Polish nationalism, for which he was eventually exiled to central Russia. He continued writing and advocating for Polish nationalism even from exile. Born in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, he is a shared literary figure in Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus. Today, the Polish government funds the Adam Mickiewicz Institute to promote Polish culture and language internationally.

Fryderyk Chopin is celebrated worldwide for his Romantic-era piano works. Born near Warsaw in 1810, he was composing by age seven and performing in aristocratic homes despite little formal training. His work combined classical and Polish folk influences, helping him to earn the status of a Polish national composer. His legacy is today honored through events like the International Chopin Piano Competition.

Marie Curie, born Maria Skłodowska in Warsaw, was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and is the only person to have ever won the award in two sciences. Her groundbreaking work in chemistry and physics came when Poland was still partitioned, making her achievements additionally important as a source of national pride and unity.

Józef Piłsudski was a revolutionary, soldier, and statesman who became the chief architect of Polish independence after more than a century of partition. In World War I he formed the Polish Legions and later assumed command of national forces, establishing a government in 1918. As head of state, he secured victory in the Polish-Soviet War of 1919–1921, earning renown for the “Miracle on the Vistula.” He stepped down in 1922, but after seeing Poland struggle to form effective democratic and economic policies, he staged a coup in 1926. He then launched reforms, including agrarian land redistribution, that stabilized the state and grew the economy until his death in 1935. Revered as the father of modern Poland, his legacy rests on restoring sovereignty and securing its survival. Today, Piłsudski Square is Warsaw’s largest open square and is dominated by a statue of Piłsudski.

Pope John Paul II was born Karol Józef Wojtyła in Poland. He devoted his life to the Catholic Church, despite Communist oppression of religion in Poland at that time. His heroism was one reason he was elected Pope in 1978. Despite resistance from Communist officials who downplayed his election, much of Poland was shocked and elated by the choice. Poles rallied for his permission to re-enter Poland in 1979, over many official objections. Conducting pilgrimages to Gdansk, Sopot, and Gdynia, the Pope electrified audiences. John Paul II campaigned for religious and political freedom in Poland, and was instrumental to the Solidarity Movement’s success. He then actively campaigned for Poland’s European Union membership. He is today Poland’s greatest modern national hero.

Lech Wałęsa was a leader of the Solidarity movement, the first independent trade union in the Soviet bloc. It played a decisive role in ending communism in Poland. He organized strikes, boycotts, and protests to support workers’ rights, actions that cost him his job as an electrician at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk. Arrested multiple times, Wałęsa nevertheless remained the symbolic face of peaceful resistance. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983 and later became Poland’s first democratically elected president, serving from 1990–95, overseeing Poland’s transition to a market economy and its reintegration into the West.

Historical Events

The following events have shaped Polish cultural identity and continue to resonate in Polish life today. Rather than simple historical milestones, these moments represent turning points in how Poles understand themselves and their place in the world. Read a full history from our sister site at GeoHistory here.

The Baptism of Poland in 966, when Duke Mieszko I converted to Christianity, is seen as the symbolic birth of the Polish state. Politically, it secured Poland’s place in Christian Europe, strengthened ties with the Papacy, and helped avoid domination by the Holy Roman Empire. Conversion of the population continued into the 13th century, and pre-Christian folk customs have endured within Catholic tradition to the present day. At the same time, a lasting bond formed between Polish identity and Catholicism. Poznań Cathedral, where Mieszko is buried, stands as a national treasure. In 1966, millennial celebrations were held under communist Poland that lasted a full year and began with a gathering of 250,000 believers at the Jasna Góra Sanctuary.

The Battle of Grunwald in 1410, where Polish and Lithuanian forces under King Władysław II Jagiełło and Grand Duke Vytautas defeated the Teutonic Order, was one of medieval Europe’s largest battles and a turning point in regional power. Politically, it halted Teutonic expansion, strengthened the Polish-Lithuanian alliance, and elevated Poland’s Jagiellonian Dynasty as a major European force. In Polish memory, Grunwald symbolizes unity and resilience, celebrated through art in pieces such as Jan Matejko’s monumental 1878 painting Battle of Grunwald, Henryk Sienkiewicz’s novel The Knights of the Cross (and its 1960 film adaptation), as well as major monuments in Kraków and Warsaw. The battlefield itself hosts a museum and annual reenactments, while countless streets and squares named “Grunwald” embed the victory into daily life, making it a lasting emblem of Polish strength and independence.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was established in 1569 through the Union of Lublin under the Jagiellonian Dynasty. It united Poland and Lithuania into one political entity, creating one of Europe’s largest, most populous, and most influential states. Also known as the First Polish Republic, the Commonwealth is celebrated as a period of “Golden Liberty” which fostered political innovation, the development of democratic freedoms, cultural flourishing, and relative religious tolerance. The Castle of Wawel symbolises the power of that period as does the memory of the Winged Hussars, an elite heavy cavalry force that were instrumental in halting Ottoman expansion into Europe under King John III Sobieski. This Golden Age of Polish statehood also gives it a shared history and heritage with areas of Lithuania, Ukraine, and Belarus that it once ruled.

The Deluge, known in Polish as the “Potop,” refers to the mid-17th-century devastation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, particularly the Swedish invasion of 1655–1660, which followed the brutal Cossack Khmelnytsky Uprising and concurrent wars with Russia and the Ottoman Empire. Though the invaders were repelled and uprisings quelled, the Commonwealth was left economically, demographically, and politically weakened. It sparked a long decline that culminated in the 18th-century partitions. The era also saw heroic resistance, especially from the Catholic Church and peasant communities, as immortalized in Henryk Sienkiewicz’s 1886 novel The Deluge and continues to be referenced in political rhetoric and modern culture as a cautionary tale of the price of disunity.

The Partitions of Poland (which was then known as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) happened in three stages, with land divided among Russia, Austria, and Prussia. The first two, in 1772 and 1792, followed wars with Russia. After a failed Polish rebellion, a final partition in 1795 wiped Poland and Lithuania both from the map for 123 years. Despite this, Polish identity and resistance remained strong. Language, culture, and Catholicism served as unifying forces, especially under non-Catholic rulers. Poland was eventually reestablished after World War I through international agreements, influenced by Western leaders, Polish exiles, and immigrants, with the aim of weakening Germany and Russia. The partitions serve as a powerful lesson: Poland endures through its culture and alliances, an idea that continues to influence the Polish national identity today. This episode also lives on in the term “Fourth Partition,” often used by Polish historians to describe nearly any modern loss of land to foreign invaders.

The Second Polish Republic, founded in 1918 after 123 years of partition, restored Polish sovereignty through both diplomacy and military victories, including the “Miracle on the Vistula” led by Józef Piłsudski. In national memory, it is celebrated as a resurrection of the nation akin to Christ’s and a triumph of cultural survival against overwhelming odds. However, stitching together the three partitioned pieces, which had developed their own political, legal, and social traditions, proved immensely challenging. The republic navigated severe social and economic crises and experienced both often-deadlocked democracy and authoritarian rule under Piłsudski. Despite its instability and flaws, it served as a vital school of statehood, preparing Poles for survival and eventual rebuilding after WWII. Its destruction in 1939, at the start of WWII, is considered a national tragedy.

World War II and Communist rule are both remembered as national tragedies. WWII began in 1939, with the coordinated invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and the USSR under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. By 1941, however, the Nazis controlled all of Poland. They made it the Holocaust’s epicenter, constructing five extermination camps and murdering over 5.6 million Polish citizens, including nearly all of Poland’s Jews. The Polish Home Army, one of Europe’s largest resistance forces, led the 1944 Warsaw Uprising, and eventually eventually pushed the Nazis out. The Soviets, withholding their promised supporting advance, allowed the Nazis to destroy the Home Army as the Nazis retreated. The Soviets then claimed the city and installed a communist regime, the People’s Republic of Poland, which is today remembered primarily for censorship, shortages, state violence, and political imprisonment. WWII is seen as both a tragedy and a testament to Polish courage, reflected in art, film, and monuments. Communist rule, like the earlier Partitions, is remembered as a time when national identity, faith, and resistance sustained the spirit of independence that eventually fueled Poland’s return to democracy. Both also raise sensitive debates about guilt and collaboration.

Solidarity, or Solidarność, is a trade union founded in 1980 that played a major role in bringing down the Communist state. After decades of violent crackdowns on worker protests against social and economic conditions, the Party was finally forced to negotiate during the 1980 nationwide strike. Among other concessions, workers won the right to legally establish Solidarity, a new, self-governing trade union outside of Communist control. It evolved into a nonviolent liberation movement, disseminating information and mobilized public opinion through vigils, hunger strikes, and other means. The union came to unite diverse swaths of society and grow to 10 million members, making it the largest social movement ever. Fearing its effectiveness, martial law was declared in late 1981 in an attempt to suppress its democratic movement. However, Solidarity persisted with both grassroots and international support from figures like John Paul II. Martial law ended in mid-1983, and, by 1989, the Communist state was compelled to hold semi-free legislative elections. The Solidarity Citizens’ Committee, led by Lech Wałęsa, organized the opposition and swept all freely contested legislative seats, setting the stage for new legislation and constitutional amendments that would banish one-party rule and establish a free, independent, and democratic Polish republic. While many Poles disagree with the perceived leniency provided to former Communist officials as Poland entered this new era, the movement and its leaders are generally revered as the founding fathers of the reborn nation, who not only restored Polish freedom, but set in motion the fall of communism throughout Central and Eastern Europe.

The 2010 Smolensk plane crash killed President Lech Kaczyński and nearly 100 senior politicians and officials including religious and high military. They had been en route to the Katyn Forest in Russia to observe the anniversary of the WWII Soviet massacre of Polish army officers that had happened there. Polish and Russian investigations officially ruled that pilot error in dense fog caused the accident. However, conspiracy theories spread, fueled in part by Russia’s refusal to return the wreckage of the plane. After regaining power in 2015, the conservative PiS party formed a new commission alleging Russian involvement and a cover-up by former Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s government. Thus, the crash caused a national tragedy, a major international incident, an abrupt turnover and loss of national leadership, and a deepening of political and social divides in Poland.

Diversity in Poland

Poland has extraordinarily low numbers of minorities among its citizens. However, it does have historically important groups, a large population of Ukrainian refugees (a majority of whom are legal residents, but not counted in the census), and culturally important indigenous groups.

Jews were granted special privileges under the Magdeburg rights in the 10th century—later expanded by Casimir the Great in the 14th, making Poland a refuge as conditions worsened for Jews across Europe. The country, whose name coincidentally resembles the Hebrew phrase “lodge here,” became a new “Promised Land” for ten to Israel or the U.S. Today Jews make up less than 1% of Poland’s population. About 80% of North American Jews—and a majority worldwide—trace their ancestry to former Polish lands, meaning that Poland still plays a large role in many family histories. Karkow’s historic Jewish quarter attracts thousands for the Jewish Culture Festival, held there annually. For more about modern Judaism in Poland, see out Guide to Jewish Warsaw.

Ukrainians have long lived in Poland; the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth once ruled much of today’s Eastern and Central Ukraine. After communism fell, Poland developed close ties with Ukraine, and many Ukrainians arrived as migrant workers. Most present in the country today, however, came in 2022, when Polish families and the Polish state helped host millions of Ukrainians seeking refuge from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Today, an estimated 1–1.5 million Ukrainians live in Poland—about 3% of the population, up from roughly half that share before the war. Concentrated in urban areas, nearly one million hold protected refugee status, though many others remain without legal documentation. Poland’s simplified temporary protection regime has granted those with status legal residency, work rights, child allowances, and access to education, healthcare, and registration. Despite these efforts, infrastructure has struggled to keep pace, with school integration, housing shortages, and rising rents among the persistent challenges.

Belarussians were once part of the Polish-Lithuanian empire and have long been present in Poland. After communism fell, and especially after Poland ascended to the EU, many Belarussians immigrated to Poland as migrant workers or political refugees. Today, they are estimated to number between 250,000-350,000, or less than 1% of the population. Some have legal status, and some do not.

Silesians were among the early Slavic tribes that united under Mieszko I to form Poland in the 10th century. Their name comes from the Ślężanie tribe, who settled around Mount Ślęża near modern Wrocław in the 6th century. Over the centuries, Silesia passed under the rule of Bohemia, Austria-Hungary, Prussia, and Germany. Most of Upper Silesia, now associated with mining and heavy industry, was restored to Poland after World War II, though parts remain in today’s Czech Republic and Germany. This history of division has helped preserve a distinct Silesian identity, marked by a dialect rich in German and Czech loanwords and unique pronunciation, as well as a distinct cuisine and ethno-regional history. Poland does not officially recognize Silesians as an ethnicity, and many see the Silesian identity as a subgroup of Polish. In the 2021 census, about 250,000 people (~0.5% of the population) declared Silesian nationality, though the true number may be higher since it required a write-in response.

Kashubians are a West Slavic people native to northwestern Poland, closely related to Poles but with their own distinct language and traditions. Their language, Kashubian, is the only surviving remnant of the Pomeranian branch of Slavic languages, sharing many features with Polish but with loanwords, grammar, and pronunciation influenced by centuries of contact with German. It has several mutually intelligible dialects, but no standard version. Kashubians most often identify as a subcategory of Poles, but also see themselves as a distinct community with their own history, folk traditions, embroidery, music, as well as sailing and fishing traditions tied to the Baltic coast. The Polish state officially recognizes Kashubians as an ethnic minority and Kashubian as a regional language, which can be taught in schools and used in local administration. Today, there are about 200,000 officially recognized Kashubians in Poland.

Lemkos, a Carpathian highland and traditionally Eastern Orthodox people are closely related to Rusyns and Ukrainians. Their origin is debated, but they settled their homeland between the 14th and 16th centuries. After World War I, they briefly established the Lemko Republic, which sought union first with Russia and then Czechoslovakia, but was ultimately dissolved and became part of Poland. Following World War II, Poland’s communist authorities accused the Lemkos of supporting the Ukrainian insurgency and, under Operation Vistula in 1947, deported many to Soviet Ukraine and dispersed the rest across Poland. Though uprooted and deprived of territorial continuity, the Lemkos preserved their identity. Today, about 10,000 live in Poland, with numbers growing as some have returned since the fall of communism. Their homeland is now split between Poland, Ukraine, and Slovakia. While some identify as a distinct nationality and others as a subgroup of the Ukrainian people, Poland now recognizes Lemkos as a separate minority. While statements of condemnation or guilt have been issued by members of the Polish government, the wartime displacement is still subject of controversy.

You’ll Also Love

Medovukha: The King of Slavic Honey Drinks

Medovukha (медовуха) is a Slavic honey-based alcoholic beverage. It is one of the most recent and perhaps the best known iteration of a long evolutionary tree of Russian honey-based beverages that can be traced all the way back to the Old Slavs. In Russia today, some argue that a return to these honey drinks, which […]

Warsaw’s Jewish Cemeteries

Warsaw, a city deeply entwined with Jewish history, hosts two large Jewish cemeteries. Although one is currently still active, both are in states of severe disrepair. The largest of these is the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery, one of the largest Jewish burial grounds in Europe. Spanning approximately 33 hectares (about 63 American football fields), it […]

Syrniki: Not Your Average Cheese Cake

Syrniki (Сырники) are cottage cheese griddle cakes, sometimes called “cheese fritters” in English. They are generally fried in vegetable oil to create crispy-on-the-outside, soft-on-the-inside medallions of warm, creamy goodness. Drizzled with sour cream, condensed milk, and/or jam, and served for breakfast or dessert, syrniki are particularly beloved in Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, and the Baltics. […]

Polish Independence Day: Student Observations

Independence Day is celebrated in Poland on November 11th. Polish Independence Day commemorates the re-establishment of the state of Poland at the end of World War I in 1918. The holiday was abolished by the communists, but was instituted in 1989, after the fall of communism. Celebrations across the country include firework displays, concerts, and […]

Zupa Ogorkowa: Traditional Polish Pickle Soup

Polish pickle soup is similar to pickle-based soups that can be found across the Slavic world. In Russia, for instance, soups like solyanka and rassolnik are popular. Solyanka, however, prides itself on stuffing as much and as many kinds of meat into the soup as possible. Rassolnik is much more similar to Polish pickle soup […]