Navruz is a spring solstice celebration that marks the beginning of the New Year according to the traditional Persian calendar. It has been a beloved holiday for some 3,000 years, surviving cultural change caused by centuries of tumultuous history. It was once celebrated on the vernal equinox but is now celebrated on the set date of March 21st.

Navruz is a profound cultural and historical celebration marking the symbiotic relationship between humanity and the natural world, deeply embedded in the rhythms of the earth.

The holiday has long been celebrated over a wide geographic area including primarily the mostly-Muslim countries of Western Asia, Central Asia, the Caspian Sea region, and the Balkans. Navruz is an official holiday in Afghanistan, Albania, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iraqi Kurdistan, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia’s Bayan-Ölgii province, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. In Russia and the United States, Navruz celebrations are growing in popularity in large part because of the Iranian and Tajik diasporas there.

Traditions surrounding this holiday vary across the diverse cultures that celebrate it. This article will focus on the history and celebration of Navruz in Central Asia. It will also look most specifically at the traditions of Tajikistan, a Persian-speaking country, and Uzbekistan, a Turkic-speaking country.

Because Navruz has been long celebrated by diverse populations speaking very different languages, Navruz is known by many different names. Further, because it is transliterated to English from languages that use non-Latin scripts such as Arabic and Cyrillic, there are many different spellings. However, nearly all of these are phonetically similar and mutually intelligible – such as Norooz, Nawrouz, Newroz, Novruz, Nowruz, and Nowrouz. Likewise, the celebrations are also diverse, but can also be recognized by other groups as being a Navruz celebration.

The closest in phonetic pronunciation for American English for the holiday name as used in Central Asia would actually be Navruz. In Tajiki as well as other Persian languages, нав (nav) means “new” while руз (ruz) means “day.” Thus, together, Navruz means “new day.”

In her book The Spectacular State: Culture and National Identity in Uzbekistan, author Laura L. Adams defines Navruz as “a holiday of spring that celebrates the triumph of warmth and light over cold and darkness, the renewal of nature, and the beginning of the agricultural labor cycle.” UNESCO put Navruz on their Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, noting that it “promotes values of peace and solidarity between generations and within families as well as reconciliation and neighborliness.”

Navruz, viewed through a cultural anthropological lens, is not just a celebration of the new year but a rich, multi-layered event that encapsulates themes of renewal, community, and the enduring legacy of ancient beliefs in contemporary life, showcasing the intricate dance between tradition and transformation.

Navruz originated from Zoroastrianism, an ancient monotheistic religion that predates Christianity. Zoroaster, the religion’s creator, was likely born around 628 BCE and was Persian. He was highly concerned with questions of death and rebirth and how good (equated with light and knowledge) can conquer evil (equated with ignorance and darkness). Many of the stories and much of the philosophy of Zoroastrianism’s holy book, The Avesta, have parallels in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, which all originated in the same geographic region as Zoroastrainism.

Because it is so old, the beginnings of Navruz are shrouded in folklore and mystery. The Avesta mentions Navruz as one of Zoroastrianism’s seven important celebrations. That book however, was only assembled in 1323 CE, although the texts it brought together are likely much older. The Persian national epic, The Shahnameh, states that King Jamshid started Navruz to save humanity from a long winter that threatened to kill every living thing. However, King Jamshid, most historians agree, is likely an entirely fictional character of Persian mythology.

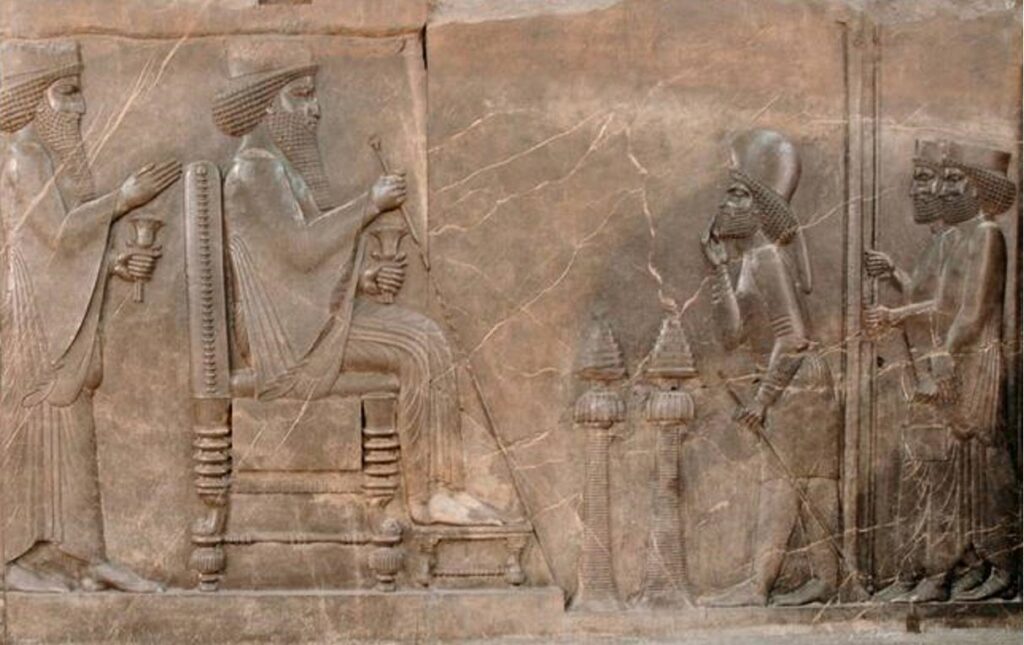

We do know that in the Achaemenid Empire, around the fifth century BCE, that Navruz was celebrated and was likely the most important holiday of the year. We know as well that it had a similar status under the Sassanids from about the 3rd to 7th centuries CE. We also know that as Zoroastrianism spread across Iran and Central Asia, it brought Navruz along with it. We know that it persisted after the arrival of Arab invaders and Islam to the area well after the 7th century CE and that, when the Russian Empire conquered Central Asia in the 1800s, Navruz celebrations also continued.

Navruz has survived revolutions and oppressive governments that have attempted to ban or coopt the holiday in recent times. Soviet Russia, post-revolution Iran, and the Taliban government of Afghanistan, for instance, all attempted to ban the holiday at some point, feeling that the ancient Zoorastrian-rooted tradition didn’t correspond with their own ideologies. However, Navruz traditions were and are still celebrated in all these affected areas.

With the fall of the USSR, Navruz celebrations have experienced a revival across Central Asia and much of the Caucuses as the peoples of each country have looked back to their pre-soviet traditions as a basis on which to build new, distinct national and ethnic identities. For many, Navruz is a powerful part of that identity.

Today, among the cultures that celebrate it, Navruz is generally seen as a new start with a clean slate. People make amends, clean their houses, and buy or make new clothes to start the New Year. It is believed that for the New Year, everything should be as if new again.

The Haft Sin Table

Navruz is marked with what is called a “Haft Sin Table.” This relatively new tradition has only appeared in the last century and requires that the table be set with seven things that start with the same letter. In Persian, this is “sin,” which is voiced as “s.” In Tajik many of the words used for the table in other Persian cultures are pronounced with a “ш” at the start. Ш is known as “shin” and voiced as “sh” in Tajik. The name of the tradition, most known internationally as “Haft Sin” and in Tajikistan as “Haft Shin” translates to “Seven ‘S’s” or “Seven ‘Sh’s.”

The items are placed on the table, often in a stylized manner, to bring good luck in the coming year. There is considerable flexibility as to what items are used, so long as their name begins with the appropriate sound in the appropriate language. In at least one Tajik celebration, the seven items used were шир (milk), шона (sprouts), шарбат (juice), шамъ (candle), шакар (sugar), шароб (wine) and ширинӣ (sweets).

Also traditional to include in a table setting are a Koran, eggs, mirrors, poetry, goldfish, and clocks. These do not necessarily fall under the Haft Sin grouping, but they do have symbolic meaning that harkens back to Zoroastrian traditions of celebrating rebirth, life, light, and knowledge.

Above: Sumalak is made for Navruz. This video shows you each step of the long and labor-intensive process.

Sprouts (шона) are particularly popular across cultures on the Haft Sin table in part because they symbolize new life and in part because they are the main ingredient in the celebration’s most popular food: Sumalak.

The sprouts must be carefully, hydroponically grown indoors with enough moisture and warmth to sprout but not rot. They must also be grown to just the right length (under 5cm), to give the sumalak its traditional sweet taste. If the sprouts get too long before it is time to cook them, the dish will be bitter.

To create sumalak, the sprouts are first ground and strained with water to create a whitish liquid. The liquid is boiled with oil and flour for hours with constant stirring. The dish is so labor intensive that it is usually done in large batches with several women helping who then share the end product. The event is often treated as a party, gathering neighbors, family members, and classmates who sing and talk together as they continually stir for hours. If done properly, the sumalak will be strikingly sweet. It can be eaten on bread or just by itself.

Other food traditions will differ from culture to culture, often with local influences affecting the traditions.

Halim is particularly well-known in Uzbekistan, for instance. Like sumalak, it is highly labor intensive, typically cooked in large batches by groups, but is traditionally cooked by men. Halim is of Arabic origin and is known as a food that was often cooked for Muslim holidays in which food was distributed to the poor. Because halim is so difficult to make, it was believed that only the most pious would make this food to give away.

Halim starts with meat seared in oil. Water is then added, as is wheat, and the whole mixture is cooked with constant, vigorous stirring until it becomes one homogenous mass with a hearty flavor and a consistency similar to melted cheese.

Above: Halim is made for Navruz in Uzbekistan. This video shows you each step of the long and labor-intensive process. It is captioned in Russian and voiced mostly in Uzbek, but also very clearly shows what is happening.

Both halim and sumalak are believed to have exceptional health-giving powers and both are believed to help rejuvenate the body after winter.

Plov, a regional favorite, is also often served. This is a simpler dish rice and meat. Tajiks will often prepare their signature oshi plov, which has chick peas added and is served with hardboiled eggs and lemon. Oshi plov is believed to create peace and community among those that eat it together.

Other traditional dishes, such as samsa, a fried pastry, and chuchvara, a dumpling, usually meat filled, are often made with vegetable filling in a nod to spring and the new availability of greens.

In many cultures that celebrate Navruz, wrestling and equestrian sports are particularly popular. As Navruz celebrates life and strength, it makes sense that sports are a big part of the festival.

Most of the cultures have a specific type of wrestling that they consider a source of national pride. For instance, the Tajiks wrestle in a style called “gushtigiri” and will tell of its connections to their ancestors, Sogdians and Bactrians. The Uzbek style is called “kurash” and has links to the national hero Tamerlane, who used the sport to train his troops.

Equestrian sports are dominated in Central Asia by a game in which one must carry a whole goat carcass while on horseback and deposit it into a goal. In Tajikistan, where the sport is known as “buzkashi,” and Uzbekistan, where it is known as “kupkari,” it is particularly chaotic, often with dozens of players all playing against each other and with almost no rules except one against knocking another player off his horse – which could result in death in such conditions. The sport takes considerable strength, a well-trained horse of great endurance, and equestrian skill. It also has historically military ties, as Central Asia’s greatest armies were equestrian.

Social hierarchy can also be seen in these games. The day often begins with boys on the field, and ends with older men. The matches are instigated by a village elder or other resected person. Older men are given the best seats from which to watch. Lastly, it is only men who participate. Women do not compete and often do not attend these matches.

Other common customs include fires. Some cultures will make smaller fires and jump over them. This tradition was once held by many cultures and is believed to give health or grant wishes. Today, the fires are more often used a space to enjoy the night with family reciting poetry or singing traditional songs.

Particularly in major cities, one can find major concerts held and other large-scale festivities. In Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, for instance, there is a parade that features the Navruz Princess, typically a young girl, as well as dancers from different regions of Tajikistan, floats showing Tajik national food, and more. In fact, in Tajikistan, Navruz is a weeklong holiday to fit in all the festivities.

In Uzbekistan, there are several rituals such as singing “Kelin salom” (“The Bride’s Hello”), a song traditionally sang at weddings. During Navruz, new brides or young women act out the Kelin salom while wearing traditional Uzbek dresses. In Uzbekistan, workers have three days off from work to celebrate Navruz.

The Tajiks also have a traditional poem to recite called the “Bakhor omad,” which tells how the New Year came in spring to renew the cycle of life.

Above: a performance of Kelin Salom in Uzbekistan.

Throughout the area that it is celebrated, Navruz represents a holiday of cleaning and cooking, of eating and spending time with loved ones, and of sport and taking joy in language, dance, and song. Navruz is also almost uniformly celebrated by people wearing their national dress showing that while this is a widespread and ancient tradition, it is very much a part of modern identities and national pride as well.

Special Contribution by Alexandra Koteva

I attended SRAS’ Spring Break: Navruz in Uzbekistan program in spring, 2023. The program tours Uzbekistan’s major cities and covers a wide swath of the country’s fascinating history and culture. A major highlight of the program was the opportunity to see Navruz. This ancient holiday is rooted in Zoroastrianism and is one of Central Asia’s biggest and most unique celebrations.

Navruz is a weeklong celebration with the most important day falling on the vernal equinox, which, in 2023, was March 21st. We got to experience the national dishes, family gatherings, traditional games, music and dances, sport competitions, fairs, and other festivities that accompany the holiday.

Most Uzbek families prepare for Navruz by dedicating an entire day to cooking traditional dishes and gathering with their family and neighbors. As part of our study tour, our guide Nodir invited us to his personal home in Khiva so we could experience how a family prepares for Navruz.

Sumalak is a food that is only prepared and eaten during Navruz. Sumalak is a thick wheat pudding that is famously labor intensive. It is prepared from sprouting wheat grains and seeds which are milled and then cooked in a cauldron over an open flame. By the time we arrived, Nodir’s family was in the stirring stage of this process, working with the traditional large dowel on a frequent basis while the mixture concentrates over a period of 24 hours. Consistently stirring the sumalak requires a number of people taking turns to make sure it doesn’t burn over its cooking time. Hence, we got to experience its tradition of bringing people together by joining the family in stirring the mixture. The savory sweet smell was heavenly.

Throughout the week, I also saw many people at the bazaars selling homemade jars of sumalak for Navruz – as not everyone has the time in modern Uzbekistan to devote to this process.

Nodir’s family also taught us how to prepare spinach samsa. Samsa is a baked pastry that usually features meat, but it is made with spinach on Navruz because it is a holiday that celebrates the spring and its fresh vegetation. We rolled out the dough, added the spinach-parsley filling, then sealed the dough before it went in the oven to bake. Nodir’s family also made Khivan flatbreads (large, round flatbreads that are imprinted with a pointillism-like bread stamp to create circular patterns) and plov with beef, chickpeas, raisins, and flavorful spices. Other foods served alongside the main dishes included nuts (peanuts and walnuts), fresh and dried fruits (in particular: apples, oranges, and mulberries), tomato and cucumber salad, meat soups, pelmeni (dumplings), and khvorost (sweet crisps made by deep frying a batter from eggs, flour, and water). I learned that it is also traditional to place wheatgrass, the same as is used to make sumalak, on the table during Navruz to symbolize renewal.

Food isn’t the only thing that brings people together on Navruz. Music and dance are major parts of the holiday. Nodir’s neighbors played music on traditional string instruments for us, and I spent hours dancing with his young daughter, Vazira.

Uzbekistan also holds several official celebrations sponsored by the government. Major parks throughout the country, particularly in the capital of Tashkent, hold large festivities for Navruz to compliment the family gatherings. These include concerts and dances and special decorations for city parks such as lit-up fountains.

I had the opportunity to visit Magic City Park in Tashkent on Navruz on my own after the conclusion of the SRAS program. Young boys and older men performed national Uzbek music on drums and wind instruments. Large crowds gathered around them and followed them as part of a parade throughout the park. The processions paused every now and then for a performance during which locals joined in dance. Local Uzbek artists also gave free public music and dance performances on the park’s concert stage later in the evening. I later strolled to Tashkent City Park, not too far away, to enjoy more live concert music, also held for the holiday.

Lastly, while in Khiva, I was able to learn some kurash at a local sports school. The visit was through the SRAS tour. This traditional form of Uzbek wrestling/martial art is often on display for Navruz. There were only two young girls there (the rest were all boys), so they were very excited to see me and another girl from the study tour interested in participating. We began by stretching and warming up before transitioning to kurash moves that involved flipping onto the ground.

While sports and feats of strength are common at spring festivals world-wide, the connection between kurash and Navruz specifically is that both are proud expressions of Uzbekistan’s ancient culture. Both have extensive histories and associations: Navruz practices date from the 8th century BC, and kurash is one of the (if not the) oldest sports in the area and remains extremely popular.

In conclusion, my time in Uzbekistan was incredible. Engaging with a foreign culture at such a close level can be challenging, but the SRAS tour gave us opportunities to openly celebrate with friendly locals. For example, preparing sumalak with a local family and learning kurash were things I would not have been able to do on my own. I cherish many memories from this Navruz trip, most of all dancing with Nodir’s daughter all evening during the Navruz preparation. I also recommended the SRAS Navruz tour because this holiday extends beyond Uzbekistan, meaning that it gives you greater regional experience as well, and it’s a great way to widen one’s cultural awareness overall.

Special Contribution by Bowie Fritsch, The University of Texas at Austin

As a student in the SRAS program in Bishkek, I got to experience Nowruz firsthand in two different countries.

My first sight of Nowruz was in Uzbekistan, where I traveled as an optional part of my program with SRAS in Kyrgyzstan. In Uzbekistan, I first encountered sumalak, a pudding made from wheat sprouts, which is exclusively made for Nowruz. During a visit to Khiva, the hometown of our tour guide, we were invited as guests to his home. There, we joined his family before a giant cauldron in front of the house where sumalak was being prepared. It has to be stirred for 24 hours, and I remember women taking turns stirring it as its preparation takes a lot of cooperation and effort. We also got to join in for some time to stir. While the sumalak was being stirred, as is tradition, there was singing and dancing, which is said to improve the sumalak by imbibing it with spiritual and physical strength and unity. Unfortunately, the sumalak would not be ready to eat until the next day, so I would have to wait to try it.

In Uzbekistan, I was also lucky enough to see kok boru, which is a traditional game played throughout Central Asia, including in Kyrgyzstan, on Nowruz and many other major holidays. Kok boru originates from the times of nomadism when it was also beneficial to keep men physically ready to defend their people and livestock. Kok boru is played by two teams of men on horseback who score by getting the ulak, which is a goat carcass, into the other team’s kazan (a pot-shaped goal). To watch the game, we gathered on a large field with about a hundred spectators. This game was relatively small as bigger kok boru games can gather considerably more. There are few boundaries or rules to the game, so we had to move around to avoid getting stampeded by the charging horses.

When we arrived back in Bishkek, Nowruz celebrations were also in progress there. The London School, where our study abroad program is held, had a small celebration with singing and games like tug of war. Traditional dishes like plov were served. The next day, I visited Ala-Too Square, where, during Nowruz, there are many games, performances, and concerts that celebrate the Spring and Kyrgyz culture. When I got there, it was raining lightly, but there was still a crowd of people. I did not stay in the square long because I had plans with my host family, but I did hear singing from a concert and saw many yurts set up. I walked throughout the square where I saw vendors selling fried bread and samalak as far as the eye could see; I also saw a few vendors selling candies and tables set up with various carnival games like a boxing arcade.

Although there are many events and festivities on Nowruz, most of my day was spent with my host family to have an iftar and celebrate the holiday. Most of Central Asia, including Kyrgyzstan, is Muslim and Nowruz falls right in the middle of another beloved holiday, the month-long celebration of Ramadan. During Ramadan, one must fast from sun up to sun down and thus one eats hearty breakfasts and large dinners to help get one through the day. The important evening meal is known as an iftar.

There were many guests and a table set with bread, borsok, sweets, and tea. Traditional foods were served, starting with salad, then shorpo soup, and later beshbarmak. There was also sumalak, which I got to try for the first time and was delighted to find it sweet and almost chocolate-like. After the meal, prayers were said, and later traditional songs were played.

I greatly enjoyed celebrating Nowruz and am thankful I could be in Kyrgyzstan during this festive time. From the food to festivities and gatherings of friends and family, Nowruz in Kyrgyzstan is a time-honored celebration of renewal, unity, and cultural heritage that serves as a poignant reminder of the timeless values that bind families and communities together.

Special Contribution by Kale Fuller, The Ohio State University

Nauruz, the old Zoroastrian new year that ushers in spring, is one of the largest holidays in Kyrgyzstan and being here in Bishkek during Nauruz was really amazing. The traditions of Nauruz are a very special way for Kyrgyz people to celebrate their heritage and practice millennia-old traditions.

Generally, Nauruz is celebrated by eating, dancing, and creating a special dish called sumalak. Sumalak is a thick brown paste made from wheat sprouts and flour, but what makes it really special is that it is made in a massive pot that is stirred for up to twenty-four hours – so it is incredibly labor intensive.

The morning of Nauruz it was absolutely pouring, but I grabbed a rain jacket and ventured to the main square at 10am, when the festivities were supposed to begin.

Despite the rain, there were more people there than normal, but it looked like the main celebration had been postponed to a time which I missed.

All day there was still an incredibly festive mood around Bishkek, every cafe and restaurant I visited that day had some sort of celebration, typically in the form of some sort of free food. Although Nauruz was originally a Zoroastrian holiday, it is now celebrated in mostly Muslim countries. Many major Muslim celebrations come with an expectation to perform acts of charity and generosity. So, for example, in a Turkish restaurant that my roommate and I went to, they gave us a small salad of carrots and cabbage, and at a cafe that I frequent they gave me a free cup of tea.

With Nauruz being such a big holiday, preparations begin early. I visited a large bazaar two days before Nauruz itself and people were already selling bottles of homemade sumalak. I began noticing Nauruz decorations a few days before the holiday itself, although these decorations were not nearly as extensive as what we have in America during the Christmas season.

The day before Nauruz, the London School, where we study with SRAS, put on a celebration and it was incredibly fun. We celebrated with all the traditional aspects of Nauruz: food, dancing, and traditional Kyrgyz games. As with many holidays in Kyrgyzstan, the table included plov, the traditional rice dish that is cooked in a cauldron-like pot called a kazan. Also on the menu was borsok, a fried dough dish, and an array of traditional drinks. My personal favorite Kyrgyz drink is chalap, a salty dairy drink that is incredibly filling.

It really struck me how similar most of the Kyrgyz games were to schoolyard games in the United States. One game was essentially duck, duck, goose but instead of tagging each other you throw a scarf and another was tug-of-war. Yet another (and my favorite) was a red-rover type game; I was too busy feasting on plov to play, but it was so fun to watch.

During the beginning of the celebration a woman in traditional garb burned evergreen wood and spread it throughout the air. This is a very old Kyrgyz tradition that is meant to get rid of negative spirits and cleanse the air, similar to the burning of sage in certain Native American traditions.

One of the most interesting aspects of the holiday to me, was the way in which it facilitates people to be proud of their Kyrgyz backgrounds. Around the time of Nauruz, and especially on the day itself, I noticed that significantly more people were wearing the traditional headwear, the distinctive Kyrgyz kalpak. The kalpak is an incredibly identifiable symbol for Kyrgyz culture and as such, is a symbol of their cultural pride.

Even now that Nauruz itself is over, there are some lingering festivities a few days after. For example, I went to a bazaar the Saturday after Nauruz and everywhere there were people buying and selling sumalak. From talking with local people and observing Bishkek the past few days, I have gathered that people really do view Nauruz as the beginning of spring and many things that come with warmer weather. For example, the sale of traditional drinks on the side of the road begins just after Nauruz.

Although incredibly few people in Kyrgyzstan would identify themselves as Zoroastrian, this holiday is really alive and well here. Not only that, but as Kyrgyzstan, like many post-soviet countries, continues to build its own national identity, Nauruz offers an amazing opportunity to celebrate in a uniquely Central Asian way.

Special Contribution by Olivia Route, The University of Pennsylvania

As soon as I knew I’d be spending time in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, I asked Google about the national holidays that would happen during my stay. Google gave me a neat little list of holidays that were mostly familiar — except for one: March 21, Nooruz.

In 2009, Nooruz was added to the UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity and is recognized as a holy day across a number of religions (including Sunni Islam and the Bahá’í Faith). In Bishkek, kids get the day off from school, most people get the day off of work, and a couple of roads are closed to make the main square (Ala-Too) a gigantic festival center.

My Bishkek Nooruz experience actually began on March 20, the Thursday before the holiday weekend. The London School (SRAS’s partner school for study abroad in Bishkek) was all decorated with balloons and banners, wishing everyone “Happy Nooruz!” The cafeteria had a free, celebratory plov (a Central Asian rice dish, usually made with lamb – ohhh so delicious) lunch in the cafeteria. I was stoked because, cool, free food – and then I found out it was better than just free food. Normally, you just whip up your plov on a typical stovetop and you’ve got a great meal, but for the holiday, the school cooks decided it would be best to prepare the plov in the traditional fashion – over a fire in a казань, a huge, shallow metal bowl, which gave the rice and lamb a hint of a smoky flavor. I could eat that plov for days. It was served with a carrot salad (shredded on top) and little pillow-like fried dough puffs called борсоки. This was just a taste of the food to come.

On March 21, I arrived at Ala-Too Square around noon to find the celebration already in full-swing. Banners hanging in store windows and in government buildings wished the crowd of people a Happy Nooruz. Parents and children held tight to balloons shaped like horses, smiley faces, and cartoon characters. Vendors circulated with tall cotton candy trees and even more balloons. Tables, overturned boxes, and car trunks were set up to sell sumolok, a traditional wheat dish prepared only for Nooruz.

A stage had been set up in the center of the square, in front of the big Kyrgyz flag there. Hundreds of people crowded around to watch children in national dress perform dances to traditional and contemporary music. So many people were in attendance that in order to see, some people stepped up onto park benches, trashcans, and the still-dry fountains that have not been turned on yet for the summer. Because Nooruz is associated with fire and light, large ribbon structures each reminiscent of a “костер” (Russian for “campfire”) flanked either side of the stage – next to four full-sized yurts.

One of my favorite performances was a group of musicians playing Kyl kyyak (a Kyrgyz wooden stringed instrument) I was impressed when the male soloist flipped his instrument, clapped, and continued playing upside down without missing a beat. I was even more impressed when the rest of the (maybe 20 person) ensemble followed suit and they played a verse or two together – upside down.

After the performances concluded, the stage was taken down and the festival continued. More food vendors appeared, and out of nowhere, photographers with big wooden “Nooruz 2014” backdrops popped up. The deal is that you pick your favorite, and take a family portrait or have your children’s picture taken in front of a big Kyrgyz flag, a mountain scene with horses, or huge bouquets of flowers (all, of course, with “Nooruz 2014” written across the top).

The crowds turned into groups of people playing games. A lawn by the main government building was covered in three different circles of people passing volleyballs. Younger teens and children played a version of Duck-Duck-Goose next to the Erkindik (Freedom) statue. The plaza in front of the National Museum turned into a battleground for the biggest, most serious Red Rover game I’ve ever seen. Groups of men timed other men hanging on pull-up bars. Another masculine event on the square was a game my host brother tells me is called “альчики,” or “асычки” which means “sheep knee-bones.” In this game, you throw big pieces of bone at smaller pieces of bones sitting on money on the ground. If you knock a small bone and the money it’s sitting on across a chalk line, you get to keep the money – kind of like a big game of marbles, but with bones and cash.

Walking around in nearby parks was equally as exciting. In addition to the games and food, music played on large speakers, people sang karaoke in a number of languages, and mini-outdoor дискотеки (dance parties) appeared in park corners. Families sat on the grass and enjoyed the food, music, and sun. I went home at around six pm and the square was still full and lively.

I’m still learning about the significance of Nooruz as a religious and international holiday, but from what I’ve read and learned so far, it’s beautiful – and has a lot of meaning beyond my fun day on the square. While writing this article here in the living room, two different sets of neighbors have come over with different foods to wish my host family a happy holiday and chat with my host mom. In his international message for the holiday this year, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called Nooruz a holiday that “celebrates diversity as a strength and as the foundation for a more peaceful and sustainable world, ” and called on all people to carry the “message of peace, unity and renewal that stands at the heart of the United Nations and at the heart of the Nowruz celebrations.” This Nooruz, I’m grateful to learn about wonderful traditions, to spend time with my host mom, and to experience Spring in Bishkek. Нооруз майрамыңыздар менен (Kyrgyz), С праздником нооруз (Russian), and Happy Nooruz to you!

You’ll Also Love

Uzbek Holidays 2026: A Complete Guide

Most of Uzbekistan’s holidays are recognizable from the old Soviet calendar, although they have been moved, refocused, and/or renamed to now celebrate Uzbekistan’s independent, post-1991 history and culture rather than that of the USSR. The major exceptions to this are two major Islamic holidays and the ancient Persian New Year celebrations that have now been […]

Halva, Halwa, Helva: A Hundred Sweets from Dozens of Cultures

Halva, the rich dessert well-loved across many cultures, is so densely filling it almost manages to feel like a meal – and not an entirely unhealthy one at that. There are more than one hundred varieties of halva, an ancient dish whose base can be flour, ground seeds or nuts, or fruit, depending on where […]

Knots of Culture: Central Asia’s Carpet Weaving Heritage

Central Asia’s rich tradition of carpet weaving reflects the region’s history, culture, and identity. From the ancient nomads of the Pazyryk Valley to the artisans of Kyrgyz yurts and the urban weavers of Samarkand, carpets have long served both practical and symbolic functions. Their materials, techniques, and motifs reflect centuries of interaction between nomadic and […]

The Talking Uzbek Phrasebook

The Talking Phrasebook Series presents useful phrases and words in side-by-side translation and with audio files specifically geared to help students work on listening skills and pronunciation. Below, you will find several useful phrases and words. To the left is the English and to the far right is the Uzbek translation. Uzbek is currently transitioning […]

Uzbekistan’s Story of Identity: Heroes, Memory, and Meaning

What shapes Uzbek national identity? The answer is complex and personal, but one key element is the Uzbek national narrative. This includes the heroes and pivotal events taught in schools, the places central to the nation’s collective memory, and the language and beliefs that frame its worldview. A national narrative goes beyond history: it is […]