As a child, I loved fairy tales, folklore, mythology, and anything that allowed me to escape into other worlds in which I could imagine having power and agency. I have hazy memories of the countless tales I devoured, and a still hazier understanding of how those tales may have played a role in my own identity development, how they may have equipped me to solve the existential quandaries encountered by children, how they may even have placed harmful assumptions about gender, age, class, and so forth deep within my impressionable young mind, where they may still lurk without my conscious knowledge.

Fairy Tales Under Critical Analysis

In his introduction to The Uses of Enchantment, Bruno Bettelheim commended fairy tales for enriching the lives of children, claiming that they can “help [them] to develop [their] intellect and clarify [their] emotions; be attuned to [their] anxieties and aspirations; give full recognition to [their] difficulties, while at the same time suggesting solutions to the problems which perturb [them]” (Bettelheim 5). All of this may be true, but many questions remain — to what degree can fairy tales fulfill these functions for children, and do these functions outweigh the negative influences of fairy tales that espouse antiquated and problematic values? How might we justify giving problematic material to impressionable young children, knowing that it might do lasting harm to their concept of self, particularly for young girls and women, who are typically offered narrow possibilities of being through fairy tales? Where do we draw the line that indicates which tales provide sufficient value and little enough harm that they ought to stay in rotation as children’s literature, and which ought to be retired to university libraries as fodder for scholars?

Though these questions are nigh impossible to answer, I will gather more information about them and hopefully somewhat demystify them through analyzing the Russian skazka (fairy tale) “Finist the Bright Falcon II,” as published in Baba Yaga: The Wild Witch of the East in Russian Fairy Tales. I will draw on the psychological approach of Bettelheim and the feminist approaches of Kay Stone and Marcia Lieberman to aid in my analysis.

Bettelheim’s work is oriented more toward locating aspects of fairy tales that can solve the developmental struggles encountered by children. Lieberman, meanwhile, is oriented more toward locating aspects of these tales that create developmental problems for children, whether that be damage to their sense of self, their aspirations for the future, or their ability to confidently navigate the world and adapt to setbacks. Lastly, Stone takes a more expansive approach, exploring both problem-solving and problem-creating aspects of fairy tales, going beyond the contents of the tales to consider the circumstances around their retelling, and going so far as to interview forty-four people in order to assess the breadth of what fairy tales can mean to real people in the real world. As Stone argues, it matters how tellers and compilers of fairy tales modify their contents, and how listeners and readers interpret those contents, and that cultural values influence all of these actions. Fairy tales are highly subjective and their meaning can vary greatly depending on the perspective of the reader or listener — as Stone suggests, “the true power of fairy tales was found precisely in this flexibility, that they are always and ever open to new reactions and interpretations at any stage of life” (Stone 36).

These two lenses, the psychological and the feminist, are not necessarily in competition, but can instead function in dialogue with one another. Together, they can enhance our understanding of the fairy tale’s troubled potential as a developmental tool for deeply complex and impressionable human beings continuously in the process of reconciling their own existence to a misogynistic, racist, classist, cold, unfeeling world, no matter their age.

Due to this complexity, my own writing on the topic will be non-linear and tangled: the lenses will not be cleanly divided up into sections, but will constantly interact with each other to inform my analysis. Utilizing these two approaches, the feminist and the psychological, I will locate problem-solving and problem-creating aspects of “Finist,” particularly with regards to gender identity, in an attempt to learn more about the potential developmental benefits and disadvantages of this story.

“Finist the Bright Falcon II” in Narrative Analysis

In The Uses of Enchantment, Bettelheim analyzes tales from a predominantly narrative standpoint to uncover psychologic implications. He does so with the assumption that the construction of meaning is the fundamental predicament of all human lives, and that this predicament begins in childhood. He argues that fairy tales are uniquely situated to assist presumably all children with this construction:

This is exactly the message that fairy tales get across to the child in manifold form:

that a struggle against severe difficulties in life is unavoidable, is an intrinsic part of human existence — but that if one does not shy away, but steadfastly meets unexpected and often unjust hardships, one masters all obstacles and at the end emerges victorious. (Bettelheim 8)

He also argues that fairy tales offer children a forum to practice wrangling dark existential questions before being confronted with them in real life, so they are emotionally prepared for death, loss, grief, and heartache when they inevitably surface.

The maiden-protagonist in “Finist” does indeed meet with severe and long-lasting difficulties, and she meets them head-on. Her sisters conspire against her courtship with the eponymous bright falcon, laying a trap that injures him, which causes him to angrily abandon her for his home in “the fiftieth kingdom, in the eightieth state” (“Finist” 23), where he becomes betrothed to a princess. After spending “many sleepless nights by the window of her bedchamber” (“Finist” 22), she resolves to leave home, telling her father, “I’m going, I don’t know where” (“Finist” 22). She orders three sets each of supplies to be forged for the journey: iron shoes, iron crutches (walking sticks), iron caps, and iron loaves of bread. A narrative technique employed in several Russian tales, these iron items indicate for readers or listeners of the fairy tale that the maiden-protagonist’s journey takes an unimaginably long time, as she must wear through all of the iron shoes, gnaw through iron loaves of bread, and so forth, before she completes her quest.

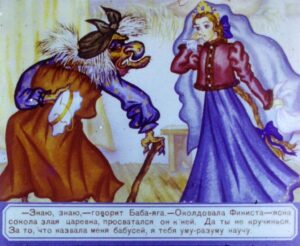

With these supplies in hand, she leaves the safety and familiarity of home to search for Finist. When each set of iron supplies runs out, she conveniently encounters a Baba Yaga in the deep dark woods. Each gives her food, advice, and some helpful items with which to win Finist back. She finally emerges from the dark forest, equipped with three items from each Baba Yaga, and uses them to bargain with the princess, Finist’s new wife, who traps the bright falcon in evil sleep charms each time the maiden-protagonist attempts to visit him. On her third bargaining attempt the maiden-protagonist is finally able to awaken Finist from the princess’s charm, and is reunited with her beloved, while the princess is executed.

While the maiden-protagonist initially wallows in heartache after the loss of Finist, her decision to take action for the sake of her own happiness is resolute and uncompromising. The three sets of iron supplies she carries on her journey through the dark forest indicate that she journeys for a long time – perhaps months, perhaps years. The forest itself could symbolize the difficult transition between childhood and adulthood, which she navigates handily with the supplies she prepares and with the mentorship of elder women she meets along the way. Her hardships are indeed unjust, as they would have been unnecessary but for the jealous conniving of her sisters, but she emerges strong and victorious, her persistence and good-naturedness allowing her to master the obstacles before her and restore her life to its proper order.

Through this genderless lens, “Finist” is nothing but a positive and motivating tale for children to identify with and learn from: it might offer an emotional framework to process perceived or real abandonment, fears of letting go of one’s parents/caregivers, or a difficult transition from one stage of life to another. I think it is well worth considering the genderless perspective, as it offers a problem-solving baseline which can then be troubled by the introduction of gender. While some children may experience adverse effects from identifying with characters of their same gender who are offered little agency, others may experience no such gendered affinity, or may not perceive negative gender stereotypes or limiting gender roles in characters who share their gender, so it is important to consider a broad range of interpretations of this story.

“Finist the Bright Falcon II:” A Feminist Reading

Bettelheim believes that gender plays an insignificant role in children’s experience of fairy tales, arguing that

“Even when a girl is depicted as turning inward in her struggle to become herself, and a boy is aggressively dealing with the external world, these two together symbolize the two ways in which one has to gain selfhood: through learning to understand and master the inner as well as the outer world. In this sense the male and the female heroines are again projections onto two different figures of two (artificially) separated aspects of one and the same process which everybody has to undergo in growing up. While some literal-minded parents do not realize it, children know that, whatever the sex of the hero, the story pertains to their own problems” (Bettelheim 226).

Stone paraphrases another of Bettelheim’s claims, that children “react unconsciously and positively, regardless of any possible surface stereotyping of the characters” (Stone 41).

I think this aspect of Bettelheim’s approach is fundamentally flawed, and severely underestimates how perceptive and impressionable young children are. They might not know what it means to be a boy or a girl, but they know which of those signifier words adults have assigned to them, and that helps them attach themselves to story characters who share that word with them.

Children notice patterns. If girl characters are consistently made passive and powerless, children will notice, and that will likely have some influence on their movement through the world, conscious or unconscious. As Stone writes, “females continue to react to [the different kinds of idealized behavior provided by fairy tale heroines] even when they consciously feel that the problem was left behind in childhood” (Stone 53). Surface level details can become embedded on deeper, unconscious levels, and stay with children throughout their development into adults.

This enculturation of limiting and even damaging gender norms early in life troubles Bettelheim’s entirely positive approach, and is one of the main concerns of Stone and Lieberman’s feminist critiques. The feminist approach is not without nuance, though, and ultimately acknowledges that some readers will locate empowerment in fairy tales, while other readers will locate oppression, and that the fairy tale is expansive enough to hold all of those meanings and still have some broader cultural coding we can all point out and agree upon.

Though Bettelheim’s psychological approach downplays the importance of gender in fairy tales, it can still be used productively in partnership with Lieberman’s gender-centric feminist approach to continue the hunt for problem-solving with regards to female sexual identity. Finist, as a man who can transform into a falcon, falls under the category of animal grooms, and both Lieberman and Bettelheim write about this topic. Lieberman’s argument about the role of animal grooms in fairy tales is particularly pointed in a footnote to her article “‘Some Day My Prince Will Come’: Female Acculturation through the Fairy Tale:” “In these stories, the girl who marries a beast must agree to accept and love a beast as a husband; the girl must give herself to a beast in order to get a man. When she is willing to do this, he can shed his frightening, rough appearance and show his gentler form, demonstrating the softening agency of women” (Lieberman 387). In other words, in other animal groom tales such as “Beauty and the Beast,” the role of female sexuality within a heterosexual context is to accept beastly men and transform them through love. In modern terms, this takes form in the “I can fix him” mindset, where women are socialized to be nurturing and emotionally mature, and are attracted to “bad boys” (whether in media or real life) who they believe they can reform into emotionally available and reciprocal partners.

The role of female sexuality in “Finist” poses a healthy alternative to the heteronormative model of female sexuality that sets women up to do all of the emotional labor in their relationships with men. In “Finist,” the maiden-protagonist knows Finist as a man and as a bird simultaneously, before ever becoming betrothed to him, so there is no process of reformation that occurs over the course of their relationship. In fact, the very first thing we learn about Finist is that he is “so good and affectionate” (“Finist” 20) to the maiden-protagonist.

Meanwhile, of animal groom tales similar to “Beauty and the Beast,” Bettelheim wrote that “One must assume that the inventors of these tales believed that to achieve a happy union, it is the female who has to overcome her view of sex as loathsome and animal-like” (Bettelheim 285). This further sets “Finist” apart as a tale that challenges the age-old expectation that women lower their standards and accept animalistic men, pointing out that if men are not loathsome and animal-like in the first place, women will not have to overcome any such impression of men.

Indeed, the maiden-protagonist is never repulsed or threatened by Finist during their initial courtship, and happily invites him into her bedroom night after night, where they talk until dawn. She is never called upon to accept a partner who is less than she deserves, emotionally or socially, or to reform that partner through her acceptance. This is a healthy relationship model for any child to observe, but I think it could play a special problem-solving role for young girls who are subject to less healthy enculturing forces from television, stories, and broad cultural messaging, who are in need of alternative narratives and characters to identify with. Such a tale might encourage young girls to have higher standards for their eventual partners, and therefore evaluate their own worth more highly, than they might otherwise have.

“Finist” has the potential to offer problem-solving not only for female sexual identity, but for male sexual identity as well. As the maiden-protagonist challenges the typical role of women in animal groom stories, Finist challenges the animal groom archetype, particularly as outlined by Bettelheim. Bettelheim suggests that as far as fairy tales are concerned, “only the male aspects of sex are beastly” (Bettelheim 285), as animal grooms usually take repulsive or dangerous forms such as bears and frogs, while animal brides are practically always lovely, often taking the forms of birds. Finist, however, has the graceful and typically feminine animal form of the falcon, and not any ordinary falcon, but one with “jeweled feathers” (“Finist” 20).

With such a radiant form, Finist offers an alternative perspective on male sexuality, not as a beastly counterpart to female sexuality but as something beautiful in its own right. It is not unreasonable to suppose that it could be damaging for young boys to form their “psycho-sexual self-concepts” (Lieberman 385), as Lieberman puts it, while inundated by messaging that their sexuality is monstrous and can only be redeemed through finding a woman who will accept them in spite of their monstrosity. Though Lieberman is interested only in female acculturation, at least in the article referenced here, acculturation impacts boys and girls alike, and patriarchal values are harmful and limiting to everyone impacted by them, not only girls. With that in mind, “Finist” offers an alternative model of heteronormative sexuality to both girls and boys, one that challenges the typical roles and limitations demarcated for each group and offers appealing figures to look up to and identify with.

All talk of problem-solving and sexual identity aside, in the majority of fairy tales, female characters are limited to being pretty, dutiful, and passive, allowing events to happen to them rather than taking action on their own behalf. Despite their oft-passive role, though, fairy tales are quantitatively dominated by female characters, and “Finist” is no different — there are a total of eight female characters of varying importance to the plot, and only three male characters. From a quantitative standpoint, female characters usually occupy a privileged position, which some scholars view as an argument for fairy tales as literature of female empowerment; however, in her book Some Day Your Witch Will Come, Kay Stone recognizes that “…the so-called “privileged position” emphasized by [Max] Lüthi is really a very restricted one” (Stone 39). Simply containing female protagonists and an overwhelming population of female characters is not enough; stories must actually give female characters power.

“Finist” offers mixed results: the maiden-protagonist is described as “such a beauty that it can’t be told in a tale or written down by pen” (“Finist” 19), but she is hardly passive, choosing to set off from home on her own in search of Finist. Lieberman makes a broad critique of the role of female protagonists in fairy tales, arguing that “Girls win the prize if they are the fairest of them all; boys win if they are bold, active, and lucky” (Lieberman 385). So far, it seems that the maiden-protagonist straddles the norm for both female and male protagonists: she is beautiful, bold, active, and lucky.

Though marriage is often the end result of fairy tales, at least in the Western canon, it is typically a bonus for male protagonists while it is typically the end goal for female protagonists, Lieberman writes. This generalization does not necessarily apply to the body of Russian fairy tales, but is interesting to consider when situating “Finist” within a more global canon of tales that influence the social and psychological development of children. Lieberman’s analysis of this pattern contends that “[in] effect, these stories focus upon courtship, which is magnified into the most important and exciting part of a girl’s life, brief though courtship is, because it is the part of her life in which she most counts as a person herself” (Lieberman 394).

In “Finist,” the maiden-protagonist’s courtship with Finist begins when her father fetches the asked-for “little scarlet flower” (“Finist” 19); from this point forward Finist flies to her bedroom every night and spends the night with her in human form. Their courtship is cut short when Finist is injured by the older sisters, causing him to abandon the maiden-protagonist, which in turn causes her to set off from home into “a deep, dark forest” (“Finist” 23) to search for him. The maiden-protagonist’s entire being is oriented toward her lover, and then toward the quest to win him back; though she plays an active role in determining her own fate, all her actions are toward the end goal of marriage to Finist, and her character is not developed outside of her quest.

However, the orientation toward marriage is not automatically a source of disempowerment. In the case of Cinderella, Stone argues that “…her marriage signified that she has managed to reject her subservient position and to take action in getting herself to the outside world, and that she has demonstrated her acceptance of maturity by entering into marriage” (Stone 45).

The maiden-protagonist of “Finist” seems to have a mediocre relationship with her parents; when she asks her father to buy her a little scarlet flower at the market, he laughs at her, saying, “And what, silly little thing, do you need a little scarlet flower for? A great lot of good it would do you. I’d do better to buy you fancy clothes” (“Finist” 19). He further infantilizes her later on, when he informs her of the condition upon which he was able to obtain the flower: that he marry her off to Finist.

The maiden-protagonist knows Finist already and is loved by him, so it seems she knew exactly what she was doing when she asked her father to fetch the flower that would signify her betrothal to Finist; however, her father’s response to this revelation is “Go to your room, my dear daughter! It’s already bedtime. Morning’s wiser than the evening. We’ll make sense of it all later” (“Finist” 20).

For the maiden-protagonist, marriage may represent an escape from an overbearing and demeaning family situation. Her quest to retrieve her betrothed may represent her rejection of her subservient position as the youngest daughter in the household, and her arduous transition into independent adulthood. Looking back at the “three pairs of iron shoes forged for her and three iron crutches, three iron caps, and three iron loaves” (“Finist” 23), all of which she wears through before reaching Finist’s home (and which signify for the reader that her journey takes an unimaginably long time), we can see that if marriage does indeed represent adulthood and freedom, then her orientation toward it and long journey to get to it could be a source of empowerment rather than disempowerment.

On her journey through the dark forest, the maiden-protagonist encounters three Baba Yagas who offer her respite and guidance. In Russian fairy tales, interactions with Baba Yagas follow gendered patterns: men typically address her rudely, demand food and drink, and receive advice or magical items, while women typically address her as a respected elder and stay with her for a period of time, serving her, before they receive advice or magical items from her. The maiden-protagonist again straddles this gendered division, treating each Baba Yaga with respect and demanding nothing from her, while also receiving food, drink, shelter, and helpful items from each Baba Yaga without having to go through a period of servitude. Her actions toward each Baba Yaga are in line with other female protagonists, but the three Baba Yagas treat her as they would treat a male protagonist, helping her as they can and sending her onward to the next Baba Yaga for further assistance. Though children reading or hearing this story likely wouldn’t be aware of this context, they may still perceive the egalitarian interactions between the young woman and older women, which are mutually respectful regardless of age.

For that matter, the maiden-protagonist’s interactions with the Baba Yagas are the only supportive relationships between women in this story. Her mother doesn’t play any role in the story, only included in the family unit as an afterthought. Her sisters act in opposition to her happiness; as soon as they realize Finist visits the maiden-protagonist in her bedroom at night, they plot to “hide knives on the window of their sister’s chamber in the evening so that Finist the bright falcon would cut his jeweled wings” (“Finist” 21). The princess who becomes Finist’s first wife competes with the maiden-protagonist, a competition that ultimately ends in the princess being “hanged on the gates and shot” (“Finist” 27) at Finist’s command. While the Baba Yagas act as supportive and helpful elders, they are not human women but supernatural entities who take female forms; according to Lieberman’s framework Baba Yagas “have gender only in a technical sense” (Lieberman 391), and therefore do not necessarily present positive examples of supportive relationships between women, depending on the reader or listener’s perception of the Baba Yaga archetype.

For these reasons, the sense of communal identity amongst women is shaky at best in “Finist;” the tale offers either few, or zero, positive models of interaction among women, and could serve to teach girls that the default way to interact with other girls is to fight with them over boys, rather than to form communal bonds that don’t revolve around boys at all (but perhaps include boys as allies and friends).

Conclusion: An Enigmatic and Fascinating Tale

“Finist the Bright Falcon II,” as translated and published in Baba Yaga: The Wild Witch of the East in Russian Fairy Tales, stands out because it is so incredibly nuanced and difficult to categorically determine to be empowering or disempowering. The treatment of gender in this tale could be considered progressive, even radical, or limiting and harmful, depending on the life experiences of the reader and the context in which they are situated. Of course, this is true for just about any fairy tale, and yet “Finist” is particularly nuanced, particularly subjective, and particularly hard to categorize because of the degree to which its maiden-protagonist blurs the lines between typical male and female roles. For these reasons, the feminist approach to this tale is very strong: it illuminates potential problems created by the maiden-protagonist’s orientation toward marriage, particularly for young girls being socialized in a heteronormative society, while also acknowledging that there can in fact be agency in the orientation toward marriage.

The psychological approach helps to broaden one’s understanding of this tale’s developmental potential, both for the creation and solution of problems with regards to social relationships, including those relationships between women and those between women and men. It also addresses sexual relationships between women and men and the individual psycho-sexual identities of women and men. Furthermore, the two main characters show significant gender ambiguity: Finist is radiant and graceful, like animal brides often are, and is rescued from an evil princess by the maiden-protagonist, who, in turn, takes male-coded social roles and takes charge of her own fate rather than waiting for rescue. Due to these ambiguous assumptions of gender roles, nonbinary children may have an easier time seeing themselves in the maiden-protagonist and Finist, and using these characters as tools for the development of psycho-sexual concepts of self beyond the gender binary.

With all of this said and done, though, I must acknowledge that my analysis ultimately amounts to so much educated guessing as to the real-world effect of this tale on the development of children. Stone’s approach to this work — interviewing a broad swathe of individuals and collecting their personal interpretations of fairy tales — would be my ideal next step with regard to “Finist” and the questions it poses. Stone asserts that all fairy tales are subjective and their meaning is dependent upon the perspective of their reader or listener, so I think it’s fitting to end with my own interpretation: that “Finist,” like many Russian fairy tales, is far more nuanced and progressive than the majority of tales in the Western canon, and as such, I believe it has the potential for greater developmental benefit and less developmental harm than the majority of fairy tales in common circulation in the United States.

Works Cited

Bettelheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. Vintage Books, 1976.

Lieberman, Marcia R. “‘Some Day My Prince Will Come’: Female Acculturation through the Fairy Tale.” College English, vol. 34, no. 3, 1972, pp. 383–95. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/375142.

Stone, Kay F. Some Day Your Witch Will Come. Wayne State University Press, 2008.

Zipes, Jack. Baba Yaga: The Wild Witch of the East in Russian Fairy Tales. Edited by Sibelan

Forrester et al., University Press of Mississippi, 2013. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt24hv8d

You’ll Also Love

Essay: My Assessment of Russian Culture

The following was written as a mid-term essay for an SRAS program in St. Petersburg. Students were encouraged to draw upon not only the program texts, but also on the impressions and experiences gained of Russia and Russians while on-the-ground in St. Petersburg. A select few of these essays have been chosen to be published […]

Essay: My Assessment of Russian Culture

The following was written as a mid-term essay for an SRAS program in St. Petersburg. Students were encouraged to draw upon not only the program texts, but also on the impressions and experiences gained of Russia and Russians while on-the-ground in St. Petersburg. A select few of these essays have been chosen to be published […]

A Russian in Ethiopia: Mutual Understanding Between Orthodox Christians in the Nineteenth Century

Because historic travel diaries by definition capture moments of cross-cultural interaction, they often preserve important evidence of interethnic -and even inter-church- solidarity and strife. This essay hones in on one nineteenth-century, non-African diarist in Ethiopia in order to better understand how international Orthodox populations have related in the past, despite differences in culture and creed. […]

Once Upon a Time in Eastern Europe: Memoirs of a Soviet Child

To the reader: These vignettes are a collection of personal essays of my childhood experiences growing up in the former Soviet Union and my later impressions based on travels to Ukraine and to Russia as a college student. Please be aware that since most of my childhood was spent in the Ukrainian SSR while it […]

The Question of Genre in Byliny and Beowulf

While stories about Dobrynya Nikitich, Ilya Muromets, and Sadko were being sung in Kievan Rus’ – the Slavic state dominated by the city of Kiev from the ninth until the twelfth centuries – Anglo-Saxon, or Old English poetry had already extended from oral to written production in the form of Beowulf.[1] Beowulf is a Christian reworking of oral […]