The history of the Russian language and its alphabet is long and fascinating. Here are a few anecdotes from the Russian language’s history.

The following is based on an article from Russian7.ru. It was translated to English and adapted for greater clarity for an English-speaking audience by SRAS and SRAS intern Sophia Rehm.

The Unprinted Letter

It is widely believed that the letter “ё” (which replaced the old letter combination “iо” and is pronounced “yo”) entered the Russian language from French solely through the efforts of writer Nikolay Karamzin. Indeed, in 1797 he rewrote the word “sliozy” (meaning “tears”) in one of his poems and declared in a footnote: “The letter with two dots replaces ‘io.’”

However, in fact, the letter was brought into use by Princess Vorontsova-Dashkova (a highly educated woman, who was president of the Academy of Sciences) in 1783. In one of the Academy’s first sessions, she asked the academics why the first sound in the word “iолка” (the old spelling for “fir-tree”) was depicted by two letters. None of the great minds there, including the notable writers Gavrila Derzhavin and Denis Fonvizin, dared to point out to the Princess that there were two sounds: “y” and “o.” So, Dashkova proposed the use of a new letter, “for the expression and pronunciation of words beginning with this sound, like “матiорый, iолка, iож, iол” (the old spellings for “full-grown,” “fir-tree,” “hedgehog,” and “ate”].”

The popularity of the letter “ё” peaked during the Stalin years: throughout the decade it was given a place of honor in textbooks, newspapers, and new editions of the classics. Today, that popularity is waning, perhaps because the letter is in a very uncomfortable position on the Russian keyboard (top right corner) and thus is falling out of favor in printed texts. It is now replaced by a simple “e,” which creates a whole new phonetic conundrum of the reader needing to remember where “e” is pronounced as “e” and where it should be pronounced as “io.”

Perhaps Russian would have been better off keeping the two-letter combination, but, for better or worse, today “ё” is more often seen in the form of stone monuments to the letter (of which there are several in Russia), than in a book or newspaper.

A Bully to Schoolboys

The letter “yat” (ѣ) was a peculiar marking that set apart “native” Slavic words from other Russian words. It was the subject of heated debate between “Westernizers” and “Slavophiles” in debates over Russian orthographic reform. It was a true torment for schoolboys, because it represented the same sound as the letter “е,” and words spelled with “yat” simply had to be memorized.

However, resourceful young minds composed a rhyme comprised only of words with “yat” in order to remember them. The rhyme read:

The white, pale, poor demon

ran hungry into the forest.

He ran through the woods like a squirrel,

and lunched on radish with horseradish.

And thanks to the bitter lunch,

he made a promise to do harm.

In the old Russian, it looked like this:

Бѣлый, блѣдный, бѣдный бѣсъ;

Убѣжалъ голодный въ лѣсъ.

Лѣшимъ по лѣсу онъ бѣгалъ;

Рѣдькой съ хрѣномъ пообѣдалъ

И за горький тотъ обѣдъ

Далъ обѣтъ надѣлать бѣдъ.

(see the full poem here)

The writer and translator Dmitry Yazykov was the first in his time to call for the abolishment of the letter “yat,” declaring: “The letter ‘yat’…resembles an ancient stone lying out of place, over which everyone stumbles but which no one moves aside, only because it is ancient and was once used for building.” In the Soviet era, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, known for his conservatism, fought unsuccessfully to bring back the “yat” in Russian grammar, along with the vowel “ъ” (“yer”). This vowel was used in Old Church Slavonic and could be read as “a” or “o” depending on its place in the word.

A Letter Worth Its Weight in Gold

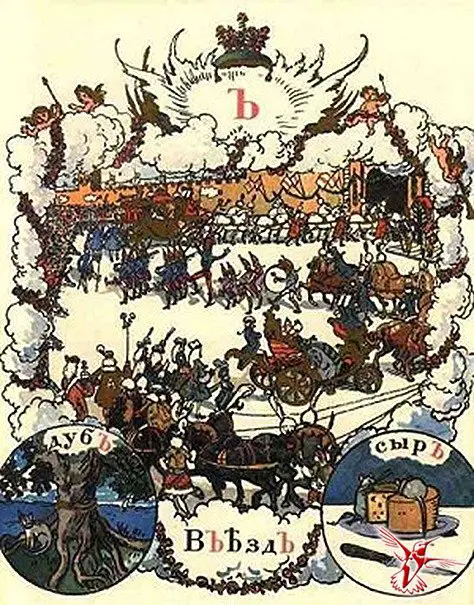

The symbol that been used for “yer” was later appropriated for a “silent” letter, one which did not denote a sound but instead served as a “hard sign.” It was traditionally written at the end of words after hard consonants until the orthographic reform of 1918. However, the letter took up more than 8% of printing industry’s time and paper, and cost Russia more than 400,000 rubles annually. Thus, it was dropped from the language in an effort to save money.

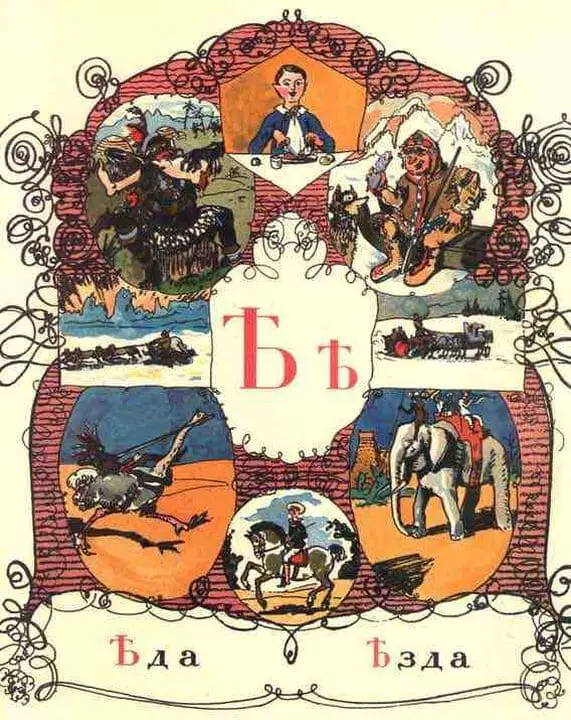

Note: the pictures for “yat” and “yer” are taken from Alphabet in Pictures by Alexander Benua, 1904. See more of his work here.

What Happens When You Lose An i

Another torment for schoolchildren was caused by the letters “и” and “i” (both usually rendered as “i” in English). When philologist reformers came to discuss which of the two letters to remove from the Russian alphabet, the matter was decided with a vote! The arguments in defense of each of them were truly arbitrary. The problem was that, in the Greek alphabet, “и” and “i” denoted two different sounds. But in Russian, by the time of Peter the Great, they were already impossible to distinguish and it was decided to simply replace “i,” when used alone, with “и.”

While this was supposed to be a simplification, making Russian spelling more phonetic, it did cause some confusion, for example, with the words “мiр” (“mir,” meaning “world”) and “мир” (“mir,” meaning “peace”). Dropping “i,” meant that the words were now written the same as well as pronounced the same, meaning that one couldn’t tell if you were demanding peace or the globe…

How a Letter Became an Insult

In Cyrillic, the letter “ф” (“f”) used to bear the fanciful name “fert.” The phrase “to stand like a fert” appeared, meaning “to stand with hands on hips.” This eventually led to “fert” being used as a name for someone in that position and then to refer to someone who habitually stood in that position. This last iteration carried the meaning of “fop” or “dandy” and was also used in the diminutive “fertik.”

Over time, the word “fert” became a pejorative, referring to a man who was unduly concerned with fashion and who, at the time, tended to pose when he stood in a position resembling a “ф.” Chekhov wrote: “There’s a fop who comes to see us with a violin, stroking away.” (“Тут к нам ездит один ферт со скрипкой, пиликает”). Pushkin wrote: “At the wall stands a young fop, like a picture in a magazine” (“У стенки фертик молодой стоит картинкою журнальной”).

Another interesting fact about the fert is that it used to have a twin. The Slavic alphabet had two letters that were most often pronounced “f” – “fert” (ф) and “fita” (ѳ; pronounced “theta” in Greek). The ѳ was used only for foreign words, particularly Greek, where the original had a “th” sound. Russian has never had the “th” sound and thus the two letters, borrowed from Greek, were pronounced the same in Russian. So, this attempt to preserve the provenance of words led to confusion. The name “Philip” was written with “fert,” while “Fyodor” was written with “fita.” Peter the Great apparently decided that this was silly and threw “fita” out of the alphabet as part of his orthographic reforms to simplify Russian.

Eh! – The Foreign Letter in the Russian Alphabet

The letter “э” was formally adopted into the Russian alphabet only in the 18th century, when Russians began seriously debating how to pronounce adopted words with the “eh” sound, as often the letter could be “eh” or “ye,” for instance. So, should it be Yevripid or Evripid (Euripedes), Yevklid or Evklid (Euclid)? The new letter was meant to resolve these conflicts, but was received with hostility. Scientist and poet Mikhail Lomonosov even wrote that “if foreign pronunciation leads to the invention of new letters, then our alphabet will end up being Chinese.”

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Encyclopedic Dictionary of F. Pavlenkov, recommended that the average intelligent person write “кэнгуру” (“kangaroo”), “кэксъ” (“cake”) and “пенснэ” (the name of the type of glasses Chekhov and Theodore Roosevelt wore).

In general, “э” still feels like a foreign letter in Russian. Perhaps this is the reason why modern Russian does not heed Pavlenkov’s advice and instead writes “кенгуру,” “кексъ,” and “пенсне.”

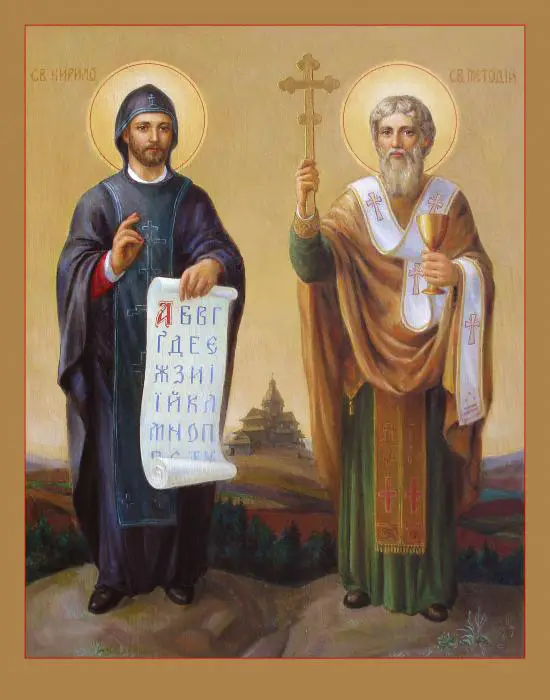

Epistle to the Slavs: A Secret Code in the Alphabet

Long ago, the Russian Orthodox Church worked out a mnemonic device in which each letter of the Cyrillic alphabet became a word, and reading these words in alphabetical order produced a text. This device works in Church Slavonic, which is only partially intelligible to modern Russian speakers.

In the original, this mnemonic device would look like this: “Азъ буки веде. Глаголъ добро есте. Живите зело, земля, и, иже како люди, мыслите нашъ онъ покои. Рцы слово твердо – укъ фърътъ херъ. Цы, черве, шта ъра юсъ яти”. Translated to modern Russian, it would look like this: “Я знаю буквы: письмо это достояние. Трудитесь усердно, земляне, как подобает разумным людям – постигайте мироздание! Несите слово убеждённо: знание – дар Божий! Дерзайте, вникайте, чтобы сущего свет постичь!”

In English, this can be translated as: “I know letters: writing is treasure. Work earnestly, people of earth, as befits rational people – comprehend the universe! Carry the word with conviction: knowledge is a divine gift! Venture forth and gain insights to comprehend the light of existence!”

Additional Resources for Understanding Russian

For a deeper learning experience, see these online and study abroad experiences from SRAS!

The Circus in Russia: Olga’s Blog

Olga here turns her attention to the modern Russian circus, describing what it is like to attend a contemporary performance, from the atmosphere inside the circus building to the acts that still draw enthusiastic audiences today. Written in simplified, modern Russian, her account offers a firsthand glimpse into how a traditional cultural institution continues to […]

The Language and History of Caviar: Olga’s Blog

Olga below describes the place of caviar in Russian food culture. In simplified Russian, she describes where the delicacy is harvested from, the major types of caviar, and how the types differ in cost and quality. We also provide an English primer below discussing more of the history of caviar, how it is eaten and […]

Mushrooms in Cultures and Cuisines: Olga’s Blog

Olga below continues her discussion of the deeply held place that mushrooms have in Russian culture. In part one of this discussion, she focused on how and where and find the mushrooms. In part two, below, she discusses how the mushrooms are preserved, prepared, and consumed. A staple of the regional diet for centuries, mushrooms […]

Mushroom Season Has Begun! Olga’s Blog

Olga below discusses the deeply held national tradition of mushroom gathering. An important part of Russian food tradition for many centuries, Russian children are taught in school from an early age to tell the difference between various types of native mushrooms. Many, like Olga, will go with relatives and friends to the woods to put […]

Study Abroad in America for Russians: Olga’s Blog

As part of her major program in international relations at Moscow State University, Olga applied to study abroad in the United States in 2007. As was not uncommon for students applying for study abroad in either direction, Olga hit several bureaucratic snags. What is perhaps most remarkable about the below text, however, is the description […]