Games such as durak, pyanitsa, and loto are known to nearly everyone in Russian-speaking cultures. While these all have close analogues in many foreign cultures, participating in the games as a foreigner can be difficult as many have highly specific jargon associated with them. The language resource below will introduce you to these games, how they are played, some of the language associated with them, as well as their history and place in modern cultures.

About Games in Russian-Speaking Cultures

Many claim that games like durak, pyanitsa, preferens, and loto are пустые и бесполезные траты времени (empty and useless wastes of time). Some claim that они даже вредны (they are even harmful). There are two major reasons for this bad reputation. The first is that the games are sometimes associated with those with too much free time. While having ample free time can be normal in some cases, it is also true of the ленивый и бездеятельный (lazy and idle), of criminals, and other unsavory types.

The second major reason is that these games can be used as азартные игры (gambling). Gambling itself is associated with зависимость и моральное разложение (addiction and moral corruption). However, most players не играют на деньги (do not play for money); they play simply to play – as a way to spend time and socialize.

Many in educated Russian-speaking societies will enter into games with an acknowledgement that it is not something a cultured person generally does. In this way, it is very much like eating sunflower seeds, a process often referred to in Russian as “щелкать семечки” (to crack seeds) or even “плевать семечки” (to spit seeds), which holds similar associations with the idle, lazy, and undesirable. However, again, the practice of eating sunflower seeds in Russia is widespread.

These games are deeply embedded in Russian-speaking cultures and nearly all adults in these cultures know how to play them. They are excellent ways to убить время (kill time) when вам нечего делать (you have nothing to do). These games are often associated with детство (childhood), with spending quiet holidays at the dacha, and with the long train rides for which Russia is famous. In the case of train rides especially, these games can be a way of bringing strangers together, creating community, and времяпровождения (passing time) in a relatively constructive way.

Because these games are so widely known, they often have “свои правила” (house rules) and variations on how they are played. Many also have similar versions in other countries that are known by different names.

These games are also не совсем “русские игры” (not really “Russian games”). Although большинство из них можно считать “русскими версиями” (most can be considered “Russian versions”) of these games, all came from other cultures originally and all are popular throughout Russian speaking countries. The fact that these games are so widespread is an indication that they are an excellent example of the universal human need to socialize.

Popular Card Games in Russian-Speaking Cultures

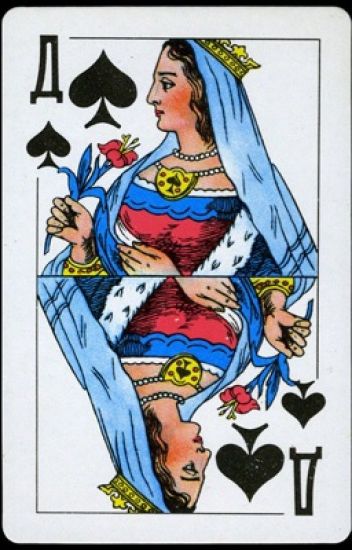

Nearly all card games begin when раздающий тасует колоду (the dealer shuffles the deck). Interestingly, the Russian word for “deck,” колоду, can also mean “block,” “log,” or “water trough.”

Cutting the deck can be referred to in Russian as “снимает шапку,” which literally means “to take off the hat.” Then, карты раздаются игрокам (the cards are dealt to the players).

Cards can be dealt лицом вверх или лицом вниз (face up or face down). “Face down” in Russian is sometimes referred to as “рубашкой вверх” – literally “shirt up” – as “shirt” is the term for the back of the card. English uses the word “jacket” for the same thing.

In many games, старшие карты играют против младших (higher cards are played against lower cards). Oftentimes, cards must be played within a certain масти (suit). Many games will also have козырные карты (trump cards).

Дурак (Durak) is one of самые популярные игры (the most popular games) in most Russian-speaking countries. The name translates as “fool” in English. In English-speaking countries, the most popular version of the game is known as “President” (or by a slew of other, often more vulgar terms). The game likely came to Russia from France after the War of 1812 – but may have also come from Japan. It was already very widespread by the time it was popularized in Russia.

В игре Дурак могут принимать участие от двух до шести игроков. (Durak can be played by two to six players.) It is typically played with колода из тридцати шести карт (a thirty-six-card deck), including лицевые карты (face cards), тузы (aces), and cards 6-10 of each suit. Durak is a trick-taking game where players take turns attacking and defending against a series of attacks. The defending player must побить атакующие карты более высокими по рангу картами той же масти или с помощью козыря (beat the attacking cards with higher-ranked cards of the same suit or by using a trump card). If the player cannot defend successfully, that player must забрать все карты, сыгранные в этот ход (pick up all the cards played in that turn). Цель игры – первым избавиться от всех своих карт. (The goal of the game is to be the first player to get rid of all their cards.) You can find a short video introduction in Russian here.

Пьяница (Pyanitsa) is similar to Durak, but highly simplified and emphasizes быстрый темп игры (fast-paced play). The name translates to “drunkard” in English. In English-speaking countries, the most popular version of this game is known as “War.”

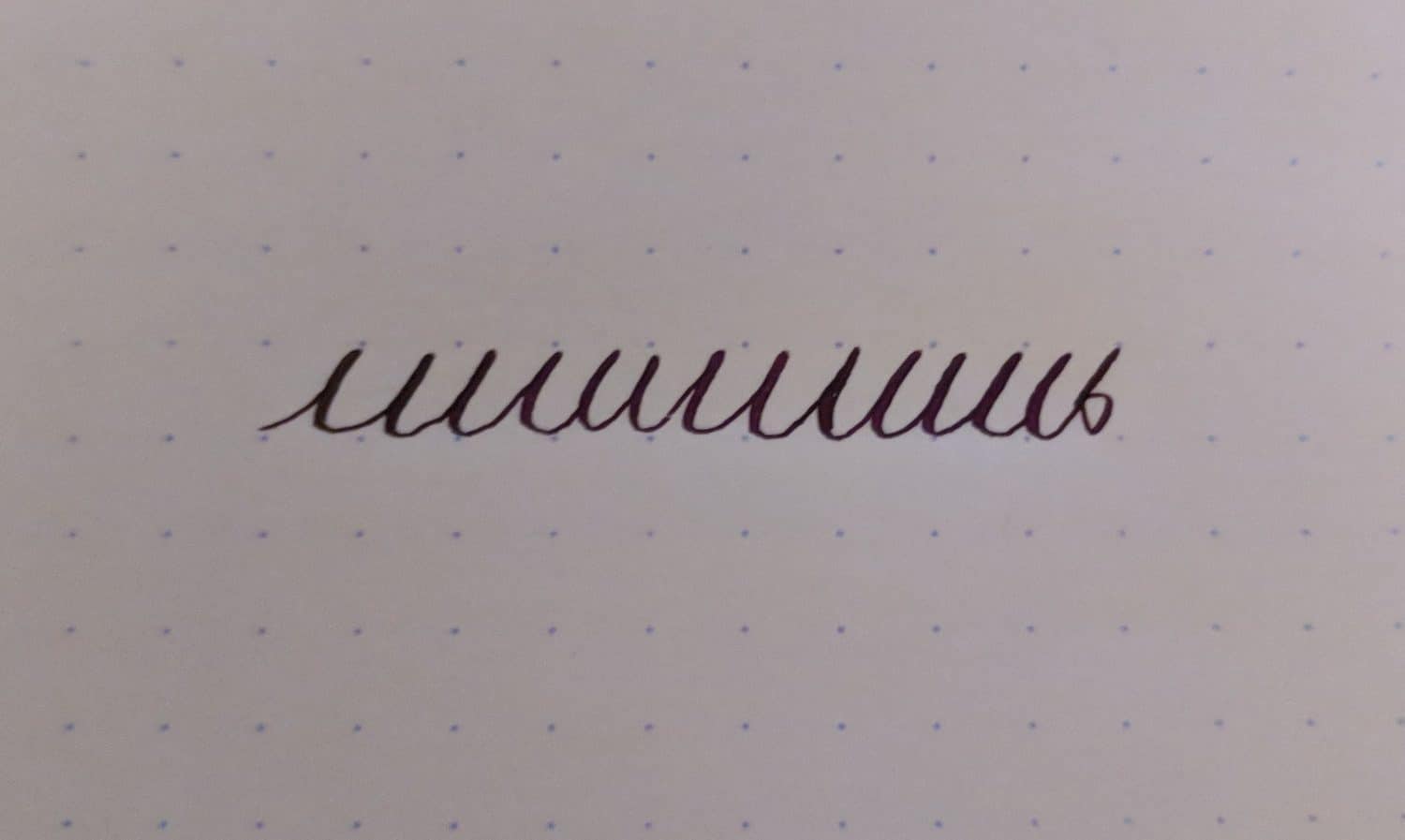

Pyanitsa is typically played by 2 players using a 36-card deck. Колода делится поровну (The deck is divided evenly) between the two players. Игроки ходят по очереди (Players take turns) revealing the top card of their stacks, and if the two cards match in rank, первый игрок, который шлепнет по стопке и крикнет “Пьяница”, выигрывает обе стопки (the first player to slap the pile and shout “Pyanitsa” wins both stacks). The goal of the game is to be первый игрок, у которого на руках все карты (the first player to hold all the cards).

Преферанс (Preferans) is a game that was very popular with the Russian aristocracy. It was adopted from the French, from whom the name was directly taken. It translates to “preference” in English and has no other meaning in Russian other than the name of the card game. In English speaking countries, the most popular version of is known as “Bridge.”

Preferans differs from Pyanitsa and Durak in that это игра, основанная скорее на мастерстве и стратегии, чем на случайности (it is a game based more on skill and strategy rather than chance). Perhaps for this reason, it is known today as a more intellectual game and one that is played by connoisseurs rather than the general public.

Preferans is played by 3 players using a 32-card deck. If more players are present, их необходимо чередовать, (they must be rotated in), as each player is initially dealt 10 cards. The remaining two cards могут быть вытянуты, если две карты сброшены (may be drawn if two cards are discarded). Players then go through a process of “contracting” and “declaration” while trying to defend their own contracts and block those of their opponents. Some versions of the game also allow for collaboration between players. The game uses a complex point system and the winner is the player набравший наибольшее количество очков (who has earned the most points) at the end of the game. You can find a whole series of lessons on the game in Russian here.

Note the differing sizes of the card decks. While Americans are used to decks with 52 cards, this is not a global standard. Most Russian games are played with 36. The 32-card deck was adopted from France.

Other Games

Лото (Loto) is another very popular game. It was first developed in Italy in the 16th century and became popular in Russia in the 18th. Loto is similar to bingo or keno.

The game is very simple. Each player is given one or more cards. Each card has three rows of five numbers each. Ведущий берет тканевый мешочек, в котором находится девяносто маленьких пронумерованных бочонков, и, не глядя, вытягивает их по одному. (The game presenter takes a cloth bag containing ninety small numbered barrels and draws them out one at a time without looking.) The presenter reads the number and the person with the corresponding number on one of their card cards берет ствол и закрывает им номер (takes the barrel and covers the number with it).

In short games, побеждает тот, кто первым завершит ряд (the person to first complete a row wins). In longer games, заполняется полная карточка (a full card should be completed) – or even a set of cards.

Камень, ножницы, бумага (Rock, Scissors, Paper) is another popular game known to most people in Russian speaking cultures. It is identical to Rock, Paper, Scissors as played in America and is popular with both kids and adults for making quick decisions.

Games have a rich tradition and are an integral part of Russian-speaking cultures. None are actually native to Russia, although many are versions of games that are now strongly associated with that culture. While gaming in general might not always have the best reputation, the rules of the game are known by nearly all, allowing the games to be ways for Russian speakers to commune and connect with one another.

More Free Russian Lessons

Russian MiniLessons: Aging

The following bilingual Russian MiniLesson is meant to build your vocabulary by providing Russian phrases within English text. Hover over the bold Russian to reveal its English translation. Most Russians feel uneasy talking about aging. There are many Russians proverbs that express a negative attitude towards old age, such as , or , or . […]

Halloween as a Case Study for Cultural Understanding

Halloween is seen around the world as an American holiday. While it has gained more global popularity in recent years, it is still really only celebrated in the US, the UK, and Canada. In most other countries, including most Slavic countries, it is regarded at most as a reason to host costume parties or perhaps […]

Russian Vocabulary: Haunted Places in Russia

Russian folklore is rich with stories of spirits, haunted places, and supernatural forces that influence daily life. These beliefs shape how certain locations, from uncivilized wilderness to abandoned homes, are viewed in the collective imagination. Unclean spirits, or нечистая сила, are believed to settle in ominous spaces like crossroads, swamps, and even ordinary houses if […]

Why Do Russians Shout «Горько!» (Bitter!) at Weddings?

The following information originally appeared as part of a longer article on The Village, a Russian-language lifestyle publication. It has been adapted by SRAS and translated here by SRAS intern Mae Liou. Gerda, a professional Russian wedding emcee: People often ask me about this, so for some time now I’ve been aware of several […]

Самый лучший разговорник – The Best Phrasebook Ever

The following list of phrases are meant as educational humor. Some are just silly, some are useful, some will be understood by all, and some only by those who have spent time in Russia. Some of these have been around online as jokes for some time – others were added based on common experiences that […]