Tucked away on a side street in central Warsaw, the heart of the city’s old Jewish center still beats within the walls of the Nożyk Synagogue. The Nożyk Synagogue was the only synagogue in Warsaw to survive the devastation of WWII. Today, it serves as the primary place of worship for the Jewish community in Warsaw. The synagogue hosts regular prayer services, including Sabbath and holiday services, and it also occasionally holds special events such as concerts.

Immediately upon learning of the existence of the Nożyk Synagogue, I knew that it was a necessary visit not only from just a historical standpoint, but also because part of my personal goals for my study abroad in Warsaw is to explore my own Jewish heritage that stems partly from Poland’s once large Jewish population.

History of the Nożyk Synagogue

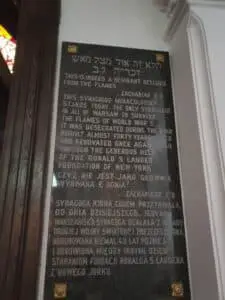

This is Indeed a Remnant Rescued From the Flames (Zachariah 3:2)

I’ve often heard Warsaw described as the “newest old city” in Europe. Due to the horrors of World War II, the beautiful city that I have come to know and love was almost completely destroyed. From the literal and metaphorical ashes, however, a new city arose stronger than ever. Warsaw’s center is a testament to the rebirth of the city — much of its old town was rebuilt literally brick by brick from the rubble left by the war and yet the larger city center is also a model of modern architectural feats.

The Nożyk Synagogue was built between 1898 and 1902 by Zalman and Rywka Nożyk, who were wealthy Jewish philanthropists who built the building as a gift to their Jewish community. Designed by well-known architect Leandro Marconi in Neo-Romanesque style, it was a relatively small synagogue in Warsaw, seating just 350. At the time, Warsaw had more than 400 synagogues, with the largest, The Great Synagogue in Warsaw, ranking as the largest in the world when it was built in 1878, with a seating capacity of more than 2000.

During the German occupation, the Nożyk Synagogue initially acted as a stable and feed warehouse for those forces. Though this gross misuse is deplorable, it spared the synagogue from the initial wave of demolishment that claimed many others. After the Nożyk Synagogue was incorporated into the “small ghetto” area, it was allowed to reopen and serve the residents of that area. It was cleaned, repaired, and reopened in 1941.

During the Warsaw Uprising, a Jewish-led rebellion, the Nożyk Synagogue was severely damaged. After the rebellion was violently put down, still more synagogues, including the Great Synagogue, which had survived until that time, were demolished by the Germans in retribution. Nożyk, however, relatively small and badly damaged, was left, almost miraculously, standing as the city’s last synagogue. It was able to be reopened yet again with provisional repairs immediately after the war and it became the new center of worship for the city’s small, remaining Jewish community.

In 1968, the synagogue was closed yet again, this time by the Communist authorities. This was part of a wave of anti-Semitism that shook the Polish Communist Party in that decade. After several student protests against censorship and Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War, Poland’s communist party leader Władysław Gomułka gave what became known as the “Zionist” speech. This speech, which marked the start of a new dark era for Poland’s Jews now plays on a loop at the POLIN museum as an important turning point in history. Jews were “dezionized” from their workplaces, and many were even stripped of their citizenship and told to exit the country for good. In addition, the Nożyk Synagogue, then still the center of Jewish life in the city, was forced closed. Services continued, but in a single room in a nearby building.

By 1977 a thaw had taken place and the Synagogue was allowed to begin extensive renovations. It was restored to its former glory and reopened again in 1983. Funded by the Ronald S. Lauder Foundation of New York, this renovation also added an office annex to the building to support the Warsaw Jewish Community Center. The center continues to provide various services to the Jewish community, including social and welfare programs, educational initiatives, and cultural activities. It serves as a hub for preserving and promoting Jewish heritage, fostering community engagement, and educating future generations about Jewish traditions and history.

Today, the Nożyk Synagogue is both open to the public and serves as a beloved place of worship yet again. It is the center of Jewish life, which can once again live and celebrate openly in the city. It is a remarkable testament to an extraordinarily resilient Jewish community in Warsaw.

Visiting the Nożyk Synagogue in 2023

From the Hotel Gromada (where students are based for SRAS programs in Warsaw over summer programs in 2023), the Nożyk Synagogue is about a 15 minute stroll. Along the way, I stumbled upon Shawarma Jaffa Tel Aviv, an Israeli restaurant complete with Hebrew writing on the awning. I stopped and checked the menu, which promised a genuine Israeli gastronomic experience. To my surprise, I’ve realized since arriving to Warsaw that there are several Israeli and kosher restaurants here.

The price to enter the Nożyk Synagogue was 20 złoty (about $5; no card accepted) — a fact that was established after a short conversation in Polish with a security guard at the entrance. The fee helps them to maintain the old structure and the organizations inside.

After crossing the threshold into the synagogue, my breath was taken away. I took in every detail, from the carpet shaped like a Star of David, to the ornate stained glass, and even to the detailed pillars. The carpet was blue, which — by coincidence or not — is a color on the Israeli flag and is often associated with Judaism as it is commonly seen in the tallit (the Jewish prayer shawl worn by men).

The stained glass appeared to me to resemble a flame burning around a Star of David sheltered by a streak of blue. Given the history of the Synagogue, I interpreted the swath of red to represent the deadly flames that destroyed all other Synagogues in Warsaw. Despite this, the Star of David (the uniting symbol of the Jewish nation) stands proud, protected by the vein of blue — the color of Judaism, as mentioned. No matter what destructive measures may be taken to eliminate the Jewish soul, the Jewish people will protect our identity and history.

Of course, my eyes were also naturally drawn to the Bimah at the central front of the Synagogue. Translated as “Elevated” from Hebrew, the Bimah is the place from which the Torah is read or lectures are given. On the eastern wall of the Synagogue, the Aron HaKodesh was situated. Translated as “Holy Ark” from Hebrew, this is where the Torah is stored; it is only opened for special occasions. This area was decorated in a manner that was perfectly fitting for its sacred nature with golden lettering and a dome.

I recommend a visit to the Nożyk Synagogue to everyone, regardless of religion. It stands as a testament to not only the continued existence of the Jewish nation, but also the resilience of Warsaw. Just as the Ner tamid (Hebrew for “Holy light”, a light in a synagogue that burns perpetually) sheds its light ceaselessly and endlessly, so will the light in the hearts of Warszavians — Jewish and non-Jewish alike — continue to shine, united by their intertwined homeland and history.

You’ll Also Love

Jewish Latvia: A Brief History and Guide

This guide offers advice to Jewish students considering study abroad programs in Latvia. Here, you’ll read about the local Jewish history, Latvia’s active synagogues, staying kosher, and about some of Riga’s major Jewish cultural organizations, museums, and memorials. Most importantly, we’ll get you on your way to engaging with the local Jewish community and comfortably […]

Jewish Georgia: A Brief History and Guide

This guide to travel in Georgia is tailored for Jewish-American university students preparing to study abroad in Georgia. We navigate the historical depth and modern vibrancy of Jewish life in this culturally rich country. Discover key historical sites, engage with local Jewish communities, and find practical tips on maintaining kosher practices and observing Shabbat while […]

Jewish Warsaw: A Brief History and Guide

This guide to travel in Poland is tailored for Jewish-American university students preparing to study abroad in Warsaw. Learn about Poland’s long Jewish history and find out where to find a kosher meal while abroad. We’ll also cover some major museums, historical sites, and day trips. Most importantly, we’ll get you moving on engaging with […]

Judaism in Russia: Моя Россия Blog

In this text, Tajik blogger Roxana Burkhanova describes, in Russian, the history of Jews in the Russian Empire, the USSR, and the Russian Federation. While the resource focuses on Russia, this also includes Jews in regions which are no longer part of Russia – including Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Central and Eastern Europe. More […]

Jewish Bishkek: A Brief History and Guide

Though the concrete details of Jewish presence in the area of Kyrgyzstan itself is largely unknown before the Soviet Union, Bukharian Jews have resided there since the 4th century. In the modern day, the population of Jews in Kyrgyzstan is estimated to be approximately 500 with most located in Bishkek. For visitors and locals alike, […]