Līgo is the most important of Latvia’s national holidays. Marking the summer solstice and rooted in pre-Christian pagan traditions, it began as an ancient ritual to secure a good harvest and help communities endure the long, harsh Lativan winter. Despite centuries of foreign occupation and efforts by both Catholic and Soviet authorities to suppress it, the holiday has endured.

Today, Līgo is a secular celebration that still honors its pagan origins. Latvians still gather for traditional foods, bonfires, and games. More than just a festive day, it is a celebration of Latvian identity and a connection to ancestral traditions.

With a long and complicated history and central place in Latvian culture, Līgo is also the source of national debate. Even its name is contested—some prefer “Jāņi” or even “Herb Day” (Zāļu diena) as more “authentically Latvian.” In modern use, however, Līgo is most commonly used to refer to the eve and Jāņi to the day after.

Regardless of the name, members of the Latvian diaspora often return home just to take part in this important cultural celebration – or they will organize celebrations abroad. One cannot understand Latvia without understanding Līgo.

The History and Traditions of Līgo

History by Nicole Cooper and Josh Wilson

Līgo has a long, varied, and often traumatic history. Yet it has remained a staple of Latvian culture and a steadfast expression of Latvian identity.

The Dainas: An Ancient Oral History of Līgo

Latvia’s Midsummer celebration honors Jāņi, an ancient figure associated with transition, change, and fertility—possibly a god or a symbolic personification of natural forces. Often depicted with two faces looking in opposite directions, Jāņi is linked to thresholds such as doorways, bridges, seasonal shifts, and celestial changes. Midsummer marked a critical threshold: the longest day of the year and the sun’s peak before its decline. The months that followed this transition would determine the success of the harvest and the community’s survival through winter.

To ensure that Jāņi’s transformative power worked in their favor, Latvians performed various rituals. Among the most important were dainas, which are short folk songs with memorable rhymes and melodies. These songs passed down cultural wisdom across generations, touching on themes such as history, morality, practical knowledge, and how to honor Jāņi for fertile fields.

The celebration’s most common name, Līgo, comes from the dainas, many of which include forms of the word līgojati (“to sway”). Swaying is central to many pagan traditions. Plants, when ripe with fruit or grain, will sway under their weight in a breeze. The cyclical back-and-forth motion can also symbolize a faith that even as warmth, wealth, and even life may ebb away, so too shall they ascend in a new season.

Midsummer rituals evolved over time with Latvian history, shaped both by natural change and external influences such as the arrival of foreign conquerors and Christianity. As these pressures began before the spread of literacy in Latvia, the dainas—though often poetic and enigmatic—serve as remarkably consistent oral histories. Alongside sources like travelers’ accounts, they offer invaluable insight into pre-literate Latvian culture, revealing a worldview rooted in reverence for the natural world.

While there are many of these songs, the one presented below is fairly representative. Others reference beer, cheese, renewal of the sun, flaming tar barrels, clean clothes, and other traditions.

| Par gadskārtu Jānīts nāca, Līgo, Līgo!

Savus bērnus apraudzīt! Līgo! Līgo! Vai tie ēda, vai tie dzēra, Līgo, Līgo! Vai Jānīti, daudzināja? Līgo, Līgo! |

For the annual season, Jāņi came, Līgo, Līgo!

To see his children! Līgo! Līgo! Did they eat, did they drink, Līgo, Līgo! Did Jāņi, sing? Līgo, Līgo! |

The Traditions of Līgo

While most of Līgo’s rituals originated in pagan belief, many live on today with a more secular or symbolic understanding. They are most often performed simply as fun or practical traditions that mark this important holiday.

Medicinal plants like clover and chamomile, thought to be most potent at Midsummer, were traditionally gathered on that day and dried for use throughout the year. In fact, another name for Midsummer is Herb Day (Zāļu diena), and herb markets still appear across Latvia on Midsummer. In a now-less-common but related tradition, girls wash their faces with morning dew, believed to carry the sun’s power and bestow beauty on this day.

Swaying, a common symbol in pagan rituals, is embodied in the wooden swings built for the holiday. The swings sought to harness the power of this motion with the belief that the more and higher you swung, the better the harvest and year ahead would be. Such swings can still be found as attractions at modern Līgo celebrations.

In the past, homes were decorated symbolically, especially around windows and doors, which were closely linked to Jāņi as thresholds of the home. Oak boughs—symbols of strength and longevity—were used. Those from trees struck by lightning were especially valued, believed to hold sky-born power. Birch branches, and sometimes whole saplings, were brought indoors because, as one of the first trees to revive after winter, birch was thought to promote healing and ward off evil. These decorations also filled homes with a fresh, earthy scent and festive leafy look. Ribbons were added as symbols of long life. Although this is more rarely done, trees remain important symbols of the holiday.

Head wreaths are still an important tradition, typically made by women. Oak leaf wreaths are given to men as wishes for strength and endurance. Unmarried women craft wreaths from fresh flowers, as symbols of beauty and fertility, often adding ribbons or beads for luck and prosperity. In the past, married women wore ornamental caps instead, although today the flower wreaths are typically worn regardless of marital status.

Wearing one’s best clothes was once an important part of the holiday. Today, many will dress in folk costumes for the occasion. Men, women, and children wear tunic-like linen shirts. Women also wear ankle-length skirts and a coat called a villaine, while men add trousers and sometimes long coats or vests. In the past, leather shoes and brooches were worn by those who could afford them, with brooches serving especially as markers of wealth.

Beer and cheese remain the most iconic Midsummer foods. Roasted meats, usually from a sheep or pig slaughtered for the occasion, are common. Traditionally, men brewed the beer while women made Jāņi cheese by combining quark, butter, eggs, and caraway seeds, then letting the mixture dry outside. Smooth, rich, round, and golden, the cheese symbolized the sun and was eaten only during Jāņi. It was even believed by some to have magical powers, with one legend saying that a girl could bewitch a young man by placing a piece under her arm before offering it to him.

Bonfires are the central element of Līgo and many other Latvian celebrations. Known for its healing and cleansing effects, the fire is most traditionally lit on a hill or other high point. Usually of wood, the fire can also come from a pole lit in a barrel of resin or tar. People sing and dance around the fire, which, in the past, was believed to promote the fertility of the sown fields. Livestock were sometimes herded around it to ensure their health and fertility as well. Handkerchiefs and old shirts could be thrown into the fire to get rid of illness and bad luck. Handfuls of ash from the fire were gathered and spread in fields and gardens.

Fortune-telling, especially about love, remains another major feature of the night. Lovers jump over fires hand-in-hand—if they land still holding hands, they are destined for happiness; if not, the relationship is doomed. In the past, unmarried girls floated their wreaths on water: if it didn’t sink, marriage would come soon. Today, floating the wreaths matters less about marital status and its staying afloat is more a general sign of good luck. Staying awake all night remains as a good omen; falling asleep before sunrise foretells a troubled year ahead.

One of the holiday’s most iconic legends is the fern flower, said to bloom only on Midsummer’s Eve. This mythical flower promises wealth, luck, and even magical powers. Boys and girls still search for it in the woods—and those who returned in pairs are thought to be destined for marriage. Of course, ferns don’t bloom, and the search is often just a playful excuse for romantic encounters.

How The Germans Helped Make Līgo Latvian

Many forces have shaped the celebration and meaning of Līgo over time. Different Latvian regions, home to distinct tribes in ancient times, still have varying traditions and cultural interaction today. Celebrations have also differed between rural areas and cities.

Christianity arrived in the 12th and 13th centuries with German merchants, missionaries, and later by force with the Teutonic Knights. Church authorities shifted the date for Līgo from the true solstice (June 20 or 21) to June 23 to align with St. John’s Eve, but otherwise had limited influence on the holiday.

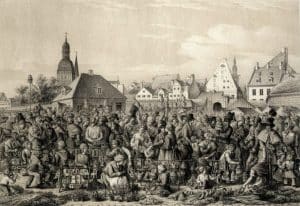

By the early 18th century, the German-speaking elite and Latvian-speaking peasantry often celebrated Līgo together. German manor lords sometimes hosted the festivities and provided the more expensive foods like meat. In Riga—then predominantly German-speaking—Līgo celebrations were shared by both Germans and Latvians. The Baltic Germans, descendants of the original conquerors, had largely assimilated into the tradition.

This began to change with the rise of the German Enlightenment and its interest in ethnography. German scholars started documenting Līgo, giving us some of the earliest extensive written sources on how it was celebrated. Yet, these accounts often included major inaccuracies—such as the claim that “Līgo” was a deity of love and friendship. In reality, Līgo is a verb or interjection in Latvian, not a noun or proper name.

“Līgo,” despite the grammatical inaccuracy, became widely applied to the holiday, with its usage traced to at least the turn of the 19th century. The term “Līgosvētki,” or “Līgo’s Eve” was further popularized by famed Latvian ethnographer Emilis Melngailis when he used it in a published work in 1900. He later felt that this had been a mistake as he said that it further displaced what he thought was the more ancient and correct name, “Jāņi.”

The academic German texts also had a tendency to describe the celebrations as primitive or offensive to Christianity. Due to this, the Baltic Germans began to distance themselves from the holiday. They still participated, but increasingly saw themselves as observers, outsiders, and commentators. At the same time, they began to judge what they saw by what they read, which also gave them preconceived expectations for the celebrations. Some Germans, worried about a loss of heritage, tried to “correct” certain traditions among the peasantry, to match the written descriptions of academics, rather than the living traditions now in place.

Thus, Līgo gradually stopped being part of a shared Latvian – Baltic German tradition. Instead, Ligo became viewed as a truly Latvian holiday.

Līgo under the Russians, Latvians, and Soviets

From 1700-1860, the Russian empire slowly took over all of Latvia, leaving the German elite in place. Russian ethnographers did not show the same interest in Latvian peasant traditions. Latvian ethnographers, however, were increasingly interested in researching and promoting their own culture and began publishing their own texts, at first mostly in German and then moving to Latvian as Latvian literacy spread and pride in the language and culture grew.

By the time the Russian conquest was complete in the 1860s, the Latvian National Awakening was already formed. Under the awakening, the Latvians began to see themselves not as a hereditary peasant class in their own homeland, but, for the first time, as a united, distinct culture equal to any other European culture.

Latvian scholars began collecting regional traditions to form a cohesive national culture out of various regional traditions. The founding of the University of Latvia during the country’s first period of independence accelerated the academic study of Līgo and helped reshape how it was celebrated. Like earlier German ethnographers, Latvian academics now sought the “correct” and most “authentic” way to celebrate.

Following Latvian independence in 1918, regional and local governments supported Līgo celebrations as a means of cultural development. Though state-supported, festivities remained decentralized and largely shaped by popular participation. In the late 1930s, under the dictatorship of Kārlis Ulmanis, the state began standardizing Līgo celebrations. The Latvian Propaganda Department became heavily involved, and from 1934 to 1939, significant resources were devoted to promoting Līgo across the country with the goal to make it “truly Latvian.”

For many Latvians, this was simply an expansion of a beloved tradition. But it also served a nationalist agenda to introduce Līgo to ethnic minorities such as Russians, Poles, and Jews to encourage cultural integration and promote Latvia as a single nation that was culturally Latvian but diverse in terms of ethnic origin.

After the Soviet occupation, early policies allowed Līgo to continue under a pan-Soviet identity, linking it to similar traditions like Russia’s Ivan Kupala. In 1941, it was even recognized as a public holiday in the Latvian SSR, with official celebrations organized by the state.

Many Latvians criticized changes made by the Soviets, arguing that they stripped the holiday of its national character. Soviet influence reshaped the celebration: vodka replaced beer, traditional songs gave way to Soviet pop and patriotic music, shashlyk became a staple food, fortune-telling was discouraged, and Soviet awards ceremonies, such as for exceptionally productive workers, were held on this day. Līgo was again used as a tool of cultural integration—this time, to absorb Latvians into Soviet identity.

As suspicion of Latvian nationalism grew, the Soviets began to repress Latvian culture. In 1941, the Soviets deported over 40,000 Latvians to Siberia and Central Asia. Līgo was removed from the official calendar that same year. Soviet propaganda labeled the holiday as both religious—due to its falling on St. John’s Day—and a distraction from labor and productivity. Celebrations were banned, but many Latvians continued to observe the holiday in secret, despite patrols and surveillance held on the day to report those who defied the ban.

The political thaw that came after Stalin’s death in 1953 allowed more open celebrations. Līgo briefly returned as an official holiday until 1959, when Latvian Communist Party leader Arvīds Pelše again denounced it as “incorrect and useless” and Līgo returned to private, almost secret celebrations.

Ligo in the Modern World

Despite various attempts to unify and suppress it, Ligo’s celebration remains widespread and varied. Many approach it as a serious endeavor, debating its proper name and how best to honor its ancient roots. Others treat it simply as a joyful national holiday—and the biggest party of the year.

Many Latvians celebrate privately at country homes. Some spend days preparing: cleaning, decorating, and making traditional Latvian foods like bacon rolls (speķrauši), Jāņi cheese, and homemade beer. Some simply purchase these foods from stores or caterers offering Līgo-specific goods and services. Often, one family hosts and invites guests who bring food and tents. The hosts play the roles of Jāņi’s symbolic “mother and father,” while guests become Jāņa bērni (“children of Jāņi”), whose presence is meant to bless the home.

Many stay in the cities, where there are lots of modern events leading up to Ligo and on the holiday itself such as folk dance and music concerts, wreath-making workshops, and, of course, herb markets. All of these took place in Riga in 2025, for example.

Traditional songs and folk costumes are still common, but many also wear everyday clothing and sing popular music as well. Rituals and their meanings vary widely by family and individual.

Above all, Līgo is a national holiday with ancient, pagan roots—one that preserved Latvian identity through centuries of occupation and hardship, and still holds meaning in today’s modern, secular Latvia. However it’s observed, and whatever it is called, Līgo remains one of the most important days of the Latvian year.

Līgo as Celebrated in 2024

By Eddy Summey, University of Texas

Walking the streets of Riga on Līgo, you will see locals wearing traditional striped outfits and bright wreaths in their hair. Pass by the market where families are selling their special holiday goods, and you can watch the children of Latvia dance to traditional music. Everywhere, food, drink, and joviality abound. When night falls, follow the locals out of the city and witness the dancing and festivities continue around bonfires large and small.

As an American student studying abroad in Latvia, I was excited to experience this local tradition myself. However, I made the very rude and culturally insensitive decision of falling ill for the solstice and was unable to attend on the day itself. However, I was still privy to the excitement and colorful days leading up to the celebrations. I also heard all about the celebrations from fellow students, who also contributed a few photos for this article. In the week after Līgo, I interviewed several locals who had celebrated Līgo their whole life to ask them about their traditions.

Everyone I spoke to agreed that Latvian families tend to have the same traditions for Līgo, and this universality is one aspect of the holiday that makes it so special.

Food and Dress

For food, the main staples are barbequed meat kebabs (shashlik) and a special yellow Līgo cheese, made with cumin. These are washed down with beer. Lots and lots of beer. As one Latvian explained: “You have to drink the beer all night, because you need to say goodbye to the sun, and then hello to the sun.” It is an all-day, all-night party. Children who cannot drink the beer typically enjoy kvass, a kind of non-alcoholic fermented soda.

Men and women will wear crowns woven from plants. These are rich with symbolic meaning. The boys and men wear oak leaves, representing strong character, while the girls wear fresh flowers, representing beauty and femininity. Married women or women who have children do not wear flower crowns until nightfall around 10 p.m., when every woman becomes young again and all women can crown themselves with flowers. Some girls throw their flower crowns onto trees or into rivers while making wishes, but many will save their crowns to burn at the start of next year’s Līgo.

Specific flowers for the crowns are not as important as freshness. Any flowers you can find can be used. However, rarely do people do roses – which are often featured in Latvian folktales as symbols of love and beauty – but most likely people prefer flowers that do not usually come with thorns. Occasionally people will do plastic flowers, but it is not very traditional – and of course, you can’t burn them the next year.

When asked about the traditional clothing Latvians wear (and if a non-Latvian should wear them to the celebrations), one local explained, “I don’t wear traditional clothes, because the clothes have traditional stripes that signify what region and village your family is from. Because my family is from Ukraine and elsewhere, I don’t have stripes. I prefer to wear something comfortable, because late in the night we take turns jumping over the big fire and I don’t want to wear anything that will catch fire.”

Song, Dance, and Ritual on Līgo

If leaping across the bonfire is not your thing, there are a lot of other Līgo traditions to partake in. The main event is the search for the mystical fern flower, a magic flower that, according to legend, appears only once every hundred years. Details about what the fern flower does are often general, like imparting the ability to talk to animals or to be led to a secret treasure. This custom is held in common with Ivan Kupala celebrations in most Slavic cultures as well.

Most commonly, this simply a way to have a bit of an adventure in the woods at night, similar to a “snipe hunt.” It is also said to be a way for young couples to escape to the woods to spend time together in honor of the fertility god. Couples who entered the woods separately but returned together were said to be destined to marry soon.

One Latvian I spoke to was very eager to explain the summer solstice market and dance performances in Riga, the tradition that takes place in the heart of Old Town:

We love dancing, even in our anthem we say, “We People Are Dancing And Singing.” This is the Latvian culture, it is in our blood. We dance and we sing songs. When our children are young, we send them to dance classes. Especially if you are fully Latvian, you will send your kids to dance classes. For most types of dance, of course you pay, but for traditional Latvian dance classes it is incredibly cheap. Sometimes, you just pay for the dresses. On all our holidays, we have people who perform songs and dances. Every four years we will also have a song and dance competition which goes seven days.

Continuing to discuss the markets, my source told me that:

It is all families who hand make things. It is a holiday market, for selling your holiday wares. You can make beer, food, dresses, honey, and meat.” She explained that certain vendors will even become family staples: “My family knows somebody with a farm and he does different types of meat. You can only buy it at the holiday market or the central market, but it is special meat, just for the people who know to ask for it.

Līgo as a Bond Between Latvians

Līgo is a time of food, song, dance, sharing, and celebrating. Above all, however, Līgo is a time of community. Every Latvian I asked to describe the most important part about Līgo said something similar to this person’s quote:

Usually we are cold people, we are not super friendly when you see us, we don’t smile or say ‘Hi! How are you?’ at all, but during Līgo, everyone is friendly. You can say ‘hi’ to everyone, you can give them beers and laugh. That is the most special part.

Or, for example:

Meeting friends and family is the most important part. We meet with all our relatives, and everyone in the community. You shouldn’t just celebrate with your small circle, you need to celebrate with everyone and say hello to the neighbors you won’t speak to next week.

Or a quote about putting aside differences and just being neighbors:

Russian-Latvians celebrate New Year’s Day more than Christmas. Latvians celebrate Christmas more than New Year. But on Līgo, everyone celebrates. Everyone loves Līgo. There is no politics, we just go outside, eat, and enjoy the night. This is very important, we don’t care about politics or religion on this day.

People and community are simply the most important part of Līgo. That is what makes Līgo so special for Latvians, and makes participating in the celebrations such a treat to experience while in the country.

You’ll Also Love

Pierogi, Pīrāgi, Varenyky: A Tour of Pastries and Dumplings

The dumplings and pastries of Europe’s northeastern flank have a story to tell. Their recipes, etymologies, and related traditions are intertwined in a complex historical knot. There are so many ancient connections that it is almost impossible to say which influenced the next. And yet, each dish is held up as a unique and integral […]

Latvia’s Story of Identity: Paganism, Heroes, and Song

What shapes Latvian national identity? The answer is complex and personal, but one key element is the Latvian national narrative. This includes the heroes and pivotal events taught in schools, the places central to the nation’s collective memory, and the language and beliefs that frame its worldview. A national narrative goes beyond history: it is […]

The Talking Latvian Phrasebook

The Talking Phrasebook Series presents useful phrases and words in side-by-side translation and with audio files specifically geared to help students work on listening skills and pronunciation. Below, you will find several useful phrases and words. To the left is the English and to the far right is the Latvian translation. In the center column […]

Jewish Latvia: A Brief History and Guide

This guide offers advice to Jewish students considering study abroad programs in Latvia. Here, you’ll read about the local Jewish history, Latvia’s active synagogues, staying kosher, and about some of Riga’s major Jewish cultural organizations, museums, and memorials. Most importantly, we’ll get you on your way to engaging with the local Jewish community and comfortably […]

Latvia’s Līgo: A Midsummer Tradition That Outlived Empires

Līgo is the most important of Latvia’s national holidays. Marking the summer solstice and rooted in pre-Christian pagan traditions, it began as an ancient ritual to secure a good harvest and help communities endure the long, harsh Lativan winter. Despite centuries of foreign occupation and efforts by both Catholic and Soviet authorities to suppress it, […]