Russian has many sayings and expressions that revolve around Moscow and places within or near Moscow. The most famous for foreigners is probably “Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears,” but there are many others such as “to yell to the whole of Ivanovskaya” and examples that might not seem to refer to a specific place such as “to put something into a long time box.” However, all these refer to real places and have real history behind them.

Let’s explore a few of these Russian sayings to understand their meaning and origin.

Орать во всю ивановскую

To yell to the whole of Ivanovskaya

This saying is well-known and widely used. Its history lies with the Moscow Kremlin. Near the Belltower of Ivan the Great, there used to lay a square called Ivanovskaya Square. It was a crowded marketplace. Like most marketplaces of the time, it was used to make purchases but also to socialize, learn news, and pass gossip. In fact, the government would place official news sources (known as “town criers” or “heralds”) in the square to call out the official news. In many European cities, this was the most common form of news broadcast and was useful when many people were illiterate and there were no newspapers or other forms of mass media.

In Moscow, and soon throughout Russia, the heralds of Ivanovksaya gave birth to a saying meaning to yell loudly for everyone to hear or to spread information indiscriminately.

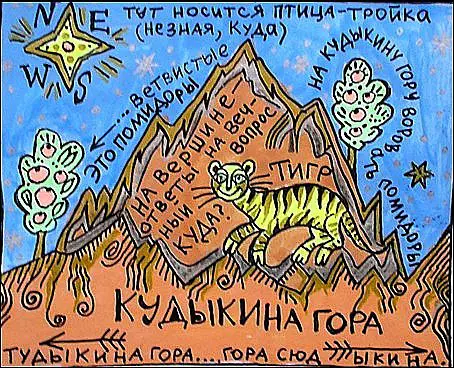

На Кудыкину гору

To Kudikino Hill

Many Russians from early childhood have answered the question “Where are you going?” with the playful “To Kudikino Hill.” This is play on words in Russian, where “kuda” means “where.”

Modern Russian uses the phrase to refer to someplace faraway and possibly imaginary. Thus, it is similar, perhaps, to the place “Timbuktu” has taken in English.

Sometimes English speakers are surprised to find out that Timbuktu is a real place. Many Russians are also surprised to find out that “Kudikino Hill” is a real location (and not that far away for many!).

The villages of Kudikino and Gora (“gora” means “mountain” or “hill” in Russian) lie in the Orekhovo-Zuevo District of the Moscow Region. Once, these were an important regional center. Nearly everyone who passed through the region and nearly everyone from the area who left on a longer trip was usually heading there. So, if someone, obviously on or preparing for long trip were asked “where are you going” the response was nearly always “Kudikino-Gora.” Eventually the phrase spread far outside the borders of the Kudikino Region and lost its connection to the actual location.

Some Russians will increase the silliness factor of the expression with “На кудыкины горы воровать (собирать) помидоры” (to Kudykino Hill to steal (pick) tomatoes) which adds an element of rhyme and whimsy.

Филькина грамота

Little Phillip’s Paper

“Филькина грамота” refers to a document which carries no legal weight. A more modern usage can also refer to an unintelligent, incompetently created document or paper. Supposedly, this expression has royal origins. Moscow Metropolitan Philip Kolychev did not approve of the Oprichnina introduced by Ivan the Terrible. Oprichnina raids of boyars’ homes, mass executions, and the terror inflicted on the people compelled the Metropolitan to protest, writing repeatedly to the Tsar and admonishing him to “come to his senses” and “return to God.” It is unknown how many letters were sent, but, according to historic chronicles, all Philip’s letters were destroyed by the Tsar and the Metropolitan himself fell into disgrace and was deposed by the Tsar.

“Filka” in Russian is a diminutive form of the name “Philip” and can be translated as “little Philip.” Such diminutives are often used to show affection for those close to you. However, when used towards a person of respect, they can have insulting connotations.

Москва слезам не верит

Moscow does not believe in tears

“Москва слезам не верит” actually became popular hundreds of years prior to the famous Russian film of the same name. (You can watch the full film for free on YouTube.)

One version of the expression’s history says that it was born in the time of the Grand Duchy of Moscow when Moscow was the official collector of tribute for the Mongols for all Russian cities. Moscow long retained this position in part because Moscow’s rulers were strict in their collections. In some cases, cities who petitioned Moscow citing unfair treatment in their tribute collection would be punished by Moscow so as to prevent others from making similar petitions.

Another, related version of the history says that the saying comes specifically from Novgorod. Novgorod was once the most powerful Russian city outside of Moscow’s direct control. Moscow annexed the city and its extensive lands in the 15th century, in a protracted, destructive, and bloody series of conflicts. The people of Novgorod are credited with coining the phrases “Москва бьет с носка” (Moscow knocks you off your feet) and “Москва слезам не потакает” (Moscow does not indulge tears).

Oткладывать в долгий ящик

To place something in the long time box.

To refer to a problem that will be put off and put off possibly forever, Russians will often say that they are “putting it in the long time box.”

The long time box really did once exist. In the 17th century, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, resolved to fight the corruption and bureaucracy of his time, installed a длинный ящик (long box) in which anyone could deposit a written complaint or petition outside his Kolomenskoye palace.

However, this didn’t last long. The Tsar got tired of reading the numerous complaints and stopped having them even removed from the box. The box itself was removed after it came to overflow. Thus, the длинный ящик (long box) became the долгий ящик (long time box): a special place to put your problems where they would never be solved.

Делу время, а потехе час

There is a time for work and an hour for play.

This phrase is not the stuff of legend, but an actual quote.

Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich was passionate about his hobby: falconry hunting. In fact, he founded Sokolniki Park (which means “Falconers Park”) as a specific place to practice the art. However, he also knew where to draw the line. A Code of Conduct written for falcon hunters, which praised, above all other activity, the pursuit of falconry hunting, the Tzar picked up a pen and added: “…правды же и суда и милостивыя любве и ратного строя николиже позабывайте: делу время, а потехе час” (“…truth and judgment, merciful love, and military service must not be forgotten: there is a time for work and an hour for fun.”