What shapes Armenian national identity? The answer is complex and personal, but one key element is the Armenian national narrative. This includes the heroes and pivotal events taught in schools, the places central to the nation’s collective memory, and the language and beliefs that frame its worldview.

A national narrative goes beyond history: it is the people, events, places, and values that define how a nation understands itself. It lives in literature, film, and art, in monuments and place names, and in the calls to action used by leaders and activists.

This resource presents Armenia’s national narrative in a concise, accessible way to help outsiders—tourists, students, and diplomats—grasp the cultural foundations of Armenian society and better understand the Armenian nation.

Religion, Language, and Ethnicity in Armenia

Armenia is over 90% ethnically Armenian. Additionally, 90% of the population identify as members of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

Resistance and honor are major themes in Armenian culture. Despite spending much of their history under foreign domination, including domination by Muslim empires and Russian-, Persian-, and Turkic-speaking empires, the Armenians have managed to keep both their unique language and Christian religion. Many of their most celebrated historical moments were moments of crisis when they preserved these elements of their identity despite extreme pressure.

To be Armenian, many Armenians have historically assumed that one should speak Armenian and follow the teachings of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Being Armenian is thus conflated both with genetic heritage but also equated with culture. This is not uncommon in Eurasia.

Catholicos Karekin II, the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church, is by far Armenia’s most highly respected and trusted public figure. The Catholicos is considered a spiritual leader and a symbol of unity for the Armenian people. According to a public opinion poll conducted by the International Republican Institute (IRI) in Armenia in 2020, Karekin II had a 58% approval rating, more than double that of any Armenian politician. Many major church services are nationally televised. Karekin II is often consulted on matters of national importance and has played a role in promoting dialogue and reconciliation between different groups in Armenia.

The Armenian Diaspora has been historically large, due in part to a long history of oppression of the Armenian people under foreign dominance, but also due to the entrepreneurial spirit of the Armenians. Today, around twice as many Armenians live outside of Armenia as inside it. Historically, this diaspora has retained its culture and language and retained links not only to its homeland but also to diasporas in other lands, building commercial networks and social support systems. Armenians tend to be commercially and politically active in their adopted lands and have often been effective lobbyists for improved foreign policy towards their homeland.

Assisting Armenians in foreign lands, particularly those facing oppression, is a strong Armenian value and matter of national pride.

Maintaining an independent Armenian state is also seen as policy imperative, as such a state has rarely existed in history and, when it has, has almost always faced intense foreign pressure within its region.

Geography in Armenian Culture

Certain places have extreme importance in Armenian culture, including some that are not inside Armenia.

Mount Ararat dominates the skyline of Yerevan. Part of the Armenian homeland for centuries, it is now located in Turkey. In Armenian mythology, Mount Ararat is believed to be the place where the gods descended from the heavens and created the world on the slopes of the mountain. Another myth holds that the first Armenian, Hayk, founded the first Armenian village and thus the Armenian nation itself, at the base of those same slopes. The mountain has been incorporated into modern Christian identity as the location that Noah’s ark came to rest after the Great Flood. Mount Ararat is foundational to Armenian culture and references to it can be seen everywhere in that culture.

Artsakh is the Armenian name for Nagorno-Karabakh. Artsakh was the name the area had when it was a province within the Armenian Empire (331 BC to 428 AD), a Golden Age for Armenians. It was the site of the Battle of Avarayr in 451, one of several battles Armenia has fought to preserve its culture and Christian faith against outside forces. Artsakh is home to numerous Armenian monasteries, churches, and cultural landmarks, many of which date back to the Middle Ages. During the early 1990s, this Armenian-majority region won defacto independence from Azerbaijan in a civil war. In this, they were heavily supported by Armenia. Although Azerbaijan also has historical ties to the land, many Armenians see this as an extension of Armenians helping each other to preserve their culture, faith, and livelihoods from outside dominance. Many Armenians feel a very strong emotional connection to the region, and the losses of the 2022 war with Azerbaijan caused a political and social crisis in Armenia. The current humanitarian crisis caused by the blockade of Artsakh is one that many Armenians are deeply pained by. The complete loss of the region to Azerbaijan would be a significant blow to Armenia’s sense of identity.

Yerevan holds 40% of the population of Armenia. The capital also accounts for some 60% of GDP and about 45% of industrial production. Armenia’s next major city is only about a tenth of Yerevan’s size. Thus, while the country has many prized natural and historic sites, Yerevan is by far the administrative, economic, and cultural capital of the country and has long been the singular destination for rural youth seeking more economic opportunity inside Armenia.

The Mother Cathedral of Holy Etchmiadzin, also known as the Etchmiadzin Cathedral is the center of Armenia’s Apostolic Church. Built in 303 AD by St. Gregory the Illuminator and St. Trdat the Great in AD 303, it is considered the oldest standing cathedral in the world and is testament to the deep and proud Christian roots of the Armenian people. It has served as the residence of the Armenian Apostolic Church’s Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos for centuries and is where many of the religion’s most important religious ceremonies take place. The Cathedral is located in the city of Vagharshapat, Armenia’s fourth largest city, which lies at the outskirts of Yerevan. The Cathedral’s architecture reflects the unique Armenian style, with intricate stone carvings and beautiful frescoes that depict important religious and historical events.

The Caucasus Mountains have helped protect Armenians for thousands of years. Their soaring peaks create microclimates that give the area the diverse range of crops and wild herbs, spices, fruits, and vegetables that has all formed the basis of Armenia’s beloved cuisine. The Caucasus Mountains also surround the people with majestic beauty every day and have been a source of inspiration for Armenian artists, writers, and musicians.

Armenian Historical Heroes

The following people have played pivotal roles in Armenia’s history and can be thought of as “founding fathers.” You may see monuments to them and places named for them.

Hayk Nahapet, according to legend, is the founder and patriarch of the Armenian nation, and the first king of Armenia. The story goes that Hayk led a group of Armenians in a rebellion against the Babylonian tyrant Bel, who had enslaved and oppressed the Armenian people. In a battle near Lake Van, Hayk challenged and killed Bel in a one-on-one fight, freeing the Armenians. Hayk is revered as a symbol of Armenian resistance and independence, themes that would come up over and over again in Armenian history as they were subjugated first by one empire and then another. The Armenians to this day call themselves “Hayq” and their country “Hayastan” after this national hero (“Armenia” comes from what the Greeks used to call them).

Saint Gregory the Illuminator converted King Tiridates III to Christianity, making Armenia the first country to adopt Christianity as its state religion. According to legend, the king was suffering from a mental illness (some stories say he had been turned into a pig by God for his sinful behavior), and that Gregory healed the pagan king, despite having been persecuted and tortured by him for refusing to worship pagan gods. Gregory founded and was the first head of the Armenian Apostolic Church and led the construction of The Mother Cathedral of Holy Etchmiadzin, now considered the world’s oldest cathedral. He also founded many schools to provide a christian education to children. Today, he is venerated as a saint in the Armenian Apostolic Church.

Mesrop Mashtots created Armenia’s unique alphabet in about 405 AD, shortly after Armenia lost its independence and was divided between the Byzantine and Persians. According to legend, he started the project after having a vision of Jesus telling him to do so. Prior to this, Armenians used other writing systems such as Greek, Syriac, and Persian. Mashtots also founded a number of schools to teach the alphabet and other subjects, spreading education. His alphabet is credited with helping Armenians remain in communication across the empires they were often divided between and helping them to retain their distinct identity. It is something that Armenians fought to keep under various empires. Today, Mashtots is revered as a saint by the Armenian Church and nearly every town and city in Armenia has a street named after him.

Movses Khorenatsi was a 5th-century Armenian historian, theologian, and philosopher. He is considered the father of Armenian historiography and is best known for his work, The History of Armenia. It covers the legendary origins of the Armenian people, the rise of the Armenian kingdoms, and the conversion of Armenia to Christianity in the 4th century. The work also includes descriptions of Armenian customs, traditions, and mythology. It helped to establish a sense of national identity among the Armenian people. Movses identified himself as a young disciple of Mesrop Mashtots and is also credited with having helped form the early direction of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Today, his image appears on the Armenian 100 dram banknote, and many streets, schools, and cultural institutions in Armenia are named after him. The History of Armenia is still studied and revered by Armenians around the world.

Mkhitar Gosh was a 12 century Armenian monk who helped shape many aspects of Armenian society. He lived and worked when Armenia was ruled by the Muslim Seljuk Empire. To make sure that Armenian Christian courts could function under the empire, he formulated the first code of laws in Armenian. He also wrote about how and why the Armenians should be ruled by an independent state. Highly concerned with morality, he also penned a volume of fables which is also considered to be the first prose work written in Armenian. Mkhitar Gosh contributed greatly to Armenian literature, philosophy, statecraft, and law as well as helped establish a strong argument for an independent Armenian state.

Tigran the Great ruled the Kingdom of Armenia from 95-55 BC, expanding Armenia’s borders from the Mediterranean Sea to the Caspian Sea, their greatest historical extent. He presided over a booming economy and funded a golden age for the Armenian arts and sciences. He built a number of impressive cities and monuments, many of which are now outside of Armenia’s current borders. Today, he is recognized as one Armenia’s greatest historical rulers.

Davit Bek rose from a probably humble background to become a soldier and then a military commander in the 18th century. He drove the invading Ottomans out of Armenia using guerrilla warfare and an intimate knowledge of his rugged homeland. Perhaps because they feared he would turn against them, the ruling Persians then made him governor of a semi-autonomous province within their empire. Bek also authored many popular songs and poems that are still performed and read today, mostly about resisting cultural domination or praising the beauty of his homeland. He has also been remembered in a litany of novels, paintings, monuments, movies, TV shows, and theatrical productions. Many streets and even a whole village are named for him in Armenia.

There are also many other leaders and military commanders who are primarily known for their resistance to domination and maintaining their moral compass. These include:

- Vartan Mamikonian was a military commander who led the Armenian forces in the Battle of Avarayr against the Sassanid Empire, defending Armenian Christianity and preserving Armenian culture and identity.

- King Pap was one of the last Armenian kings who ruled during the late 9th century and is known for his military successes against Arab and Byzantine forces.

- Ara the Handsome went to battle and later died when he refused to leave his wife for a foreign empress who desired him.

Historical Events

The Armenian Genocide (1915-1923) stands out as one of the most prominent events of modern Armenia. Approximately 1.5 million Armenians were forcibly marched into the Syrian desert by the Ottoman Empire. Nearly all died, either on the march or after being interned into camps in the desert. The Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute (AGMI) in Yerevan was established in 1995 to serve as a center for research, education, and commemoration of the genocide. The Armenian government and its diaspora have actively lobbied governments internationally to have the genocide recognized as such, but is opposed in this by Turkey, which argues that it was not a systematic extermination of the people. Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day, also known as Armenian Martyr’s Day, is observed every year on April 24th in Armenia and by Armenian communities worldwide. This day marks the first deportation of Armenian intellectuals on 24 April 1915 from Constantinople, one of the earliest events in the genocide. The day is marked by a moment of silence marked at 11:00 am, by marches of people carrying Armenian flags and pictures of the victims, religious services to mourn the victims, and other cultural events such as concerts, art exhibitions, and poetry readings. Above all, the genocide resides in the Armenian national conscious as a particularly horrific instance of oppression by an empire against an Armenian minority. This has helped re-solidify Armenian cultural values of national unity, world-wide ethnic unity, and the need for a stable, secure, and independent state for Armenians.

The First Republic of Armenia (1918-1920) lasted only for a brief period of time but remains an important part of modern Armenian history and identity. The independent state was the result of years of work by the Armenian National Movement (1860-1920), a political organization that started out seeking reforms for the Armenian minorities within Russia and the Ottoman empire. Eventually, facing stiff resistance especially from the Ottomans, the movement began to fight for an entirely independent state. When both the Ottoman and Russian Empires after WWI, Armenian political and military leaders declared an independent Armenia which was later internationally recognized by The Treaty of Sevres (1920), in which the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire agreed to the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire into several states and occupied regions. This was the first independent Armenian state since the fall of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia in the 14th century. Despite its accomplishments, the independent nation was shortly thereafter invaded and occupied by the Soviet Union. After Armenia regained its independence, it fairly quickly declared the anniversary of the founding of the First Republic a public holiday. Today, it is celebrated every year on May 28th as the Day of the First Republic. The heroes of the National Movement are celebrated as is Armenian independence in general.

Wars with Azerbaijan (1918-1920, 1988-1994, 2016, 2020, 2023) have largely defined Armenia’s recent development. At the borderlands of various empires for most of history, the peoples of the Caucasus lived fluidly and interspersed across those mountains. Under the Russians and Soviets, nationalism grew and independent homelands were sought that incorporated as much of a people’s population and historically important lands as possible. In the case of the Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the overlap in claims was enormous. Fighting first broke out in 1918, particularly over the Nagorno-Karabakh, Nakhchivan, and Zangezur regions. The war ended in 1920 when the Soviet Red Army conquered both countries. Nakhchivan remained with Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh was made an autonomous oblast within Soviet Azerbaijan, but conflict remained. In the late 1980s, Armenia demanded to unite with Nagorno-Karabakh. Clashes led to full-scale war with Azerbaijani and Armenian independence in 1991. Under a Russia-mediated ceasefire, Armenia retained Nagorno-Karabakh and adjacent regions, but the international community did not recognize the new borders. The United Nations issued several resolutions affirming Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity and calling for Armenia to withdraw. The conflict remained frozen, occasionally igniting into skirmishes, such as the Four Day War of 2016, the Second and Third Nagorno-Karabakh Wars occurred in 2020 and 2023, in which Azerbaijan took the entire territory back and the entire Armenian population of Nagorno Karabakh evacuated to Armenia. Peace talks are progressing to reset the borders back nearly to what they were under the Russian Empire and USSR. The long term effects of this prolonged and complicated conflict has been to elevate patriotism and the position of the security forces in both countries, where each has a high enlistment rate and military expenditure per capita.

Diversity in Armenia

Of course, not everyone in Armenia is Armenian. The stories and experiences of a country’s ethnic minorities are also part of the lived experience that defines it as a state.

Since Russia began what it calls its “special military operation” in Ukraine, an estimated 65,000 Russians have immigrated to Armenia, or about 2% of the overall population. Russians are probably Armenia’s single largest immigrant group now. Most are concentrated in the capital of Yerevan and thus Russian is commonly heard there and Russian cafes, music, and culture can be easily found. This was common even before 2022, as Russians were the largest tourist group in Yerevan, but it is becoming even more pronounced now. With no shared border with Russia and no current ongoing conflict with Russia, these Russians have integrated relatively well in Armenia.

Armenia’s second largest minority, the Yazidis, are believed to have migrated to the region during the 18th and 19th centuries. Today, they are less than two percent of the population. They live primarily in agricultural areas northwest of Yerevan around Mt. Aragats. The Yazidis in Armenia speak Kurmanji, a dialect of Kurdish. However, their language has been heavily influenced by Armenian and Russian.

The Yazidis are a monotheistic religious group with roots in ancient Mesopotamian religions. They believe in one God, who has delegated the management of the world to seven angels. The most important of these angels is Melek Taus (the Peacock Angel), who is often misunderstood by outsiders as the devil. The Yazidis have faced persecution from some Muslim groups who consider their religion to be heretical.

Yazidi cuisine is similar to others in the Caucasus and Central Asia with some of the most popular dishes including dolma (stuffed vegetables), kofta (meatballs), and pilaf.

The Yazidis in Armenia are recognized as an ethnic minority and have representation in the Armenian parliament. However, like other ethnic minorities in the region, they have faced challenges in terms of political representation and discrimination. The Yazidi community has been affected by the ongoing conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which has forced many to leave their homes and relocate to other areas of Armenia.

Armenia has smaller populations of Assyrianians and Ukrainians and very small populations of Jews and Greeks.

You’ll Also Love

Armenian Holidays 2026: A Complete Guide

Through these holidays, you will find Armenia is filled with a rich history revolving around nationhood, family, and religious tradition. Many holidays are particularly associated with specific monuments emphasizing the importance of place in Armenian culture. Some are ancient holidays steeped in pagan symbolism, officially repressed under the Soviets, but now newly embraced by the […]

Armenian Talking Phrasebook

The Talking Phrasebook Series presents useful phrases and words in side-by-side translation and with audio files specifically geared to help students work on listening skills and pronunciation. Below, you will find several useful phrases and words. To the left is the English and to the above right is an English transliteration of the Armenian translation. […]

Tklapi, Pastegh, Lavashak: One Ingredient Fruit Leather from the Caucasus

Fruit leather is simple, ancient food. Like bread and roasted meat, it likely independently evolved in several places. At its most basic, it is simply mashed fruit smeared to a sheet and left to dry in the sun. The result is a flavor-intensive food that travels well and can keep for months. The oldest known […]

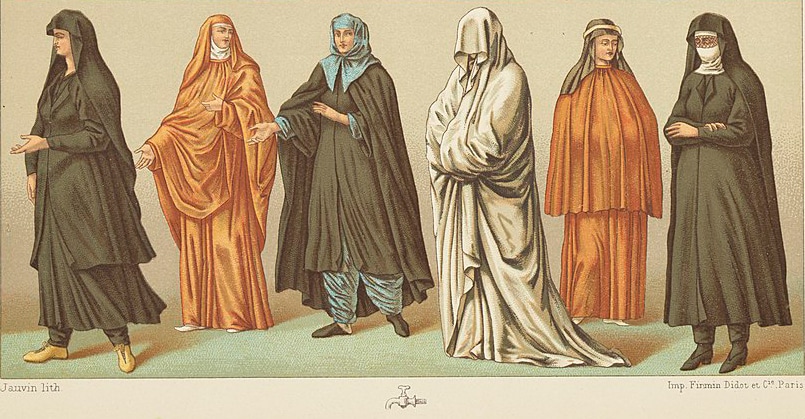

The Habits of Nuns in Catholic and Orthodox Traditions

Despite their cloistered livelihood, nuns have found their way into many veins of popular theater and movies. However, their usual depiction, wearing black habits with a veil and carrying a rosary, is not accurate for all nuns. It is true that the symbolic meaning of the habit is consistent across both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox […]

Churchkhela, Sharan, and Pelamushi: Desserts Off The Vine

Strolling through a marketplace in Georgia, you might be surprised to see the array of multicolored sausage-shaped candies hanging from the stalls. These are churchkhela, a traditional snack made by dipping strings of nuts into thickened fruit juice to create a chewy exterior. In Armenia, you’ll see “sausages” known locally as sharan that are very […]