Holidays are fascinating in how they balance the traditions of the past with the reality of the present. Remembrance and memorial days are different from most holidays in mood, but similarly balance the past and present with the hope of preserving memories for future generations.

This article looks specifically at the Deportation Remembrance Day of the Chechens and Ingush (marked on February 23rd) and covers the background history and current practices of this solemn day of remembrance and mourning.

Soviet Deportations

Even prior to the Soviet Union, Imperial Russia had long deported dissidents and criminals to Siberia. However, what would happen during the Soviet era was of a whole different scale, part of what became collectively known as the “Stalinist Terror.”

Beginning in 1937 with the Soviet Koreans of the Far East, the Soviet government instituted a practice of designating entire ethnic groups as “traitor nations” and deporting them from their homelands to other locations in the USSR – often to Central Asia. Central Asia was used as a land that was considered secure, underpopulated, and marked by the authorities for development.

These ethnic groups, which often resided in or were indigenous to border regions, were accused of plotting against the Soviet government and, as punishment, were collectively rounded up and deported. The deportees were allowed to bring very few personal belongings and were most often transported in crowded cattle cars to what was supposed to become their new home.

Needless to say, the manner in which they were transported, coupled with their arrival to an entirely new environment that was often under-equipped to support them, meant that many perished along the way or soon after arrival from disease, hunger, or exposure to the elements.

The peak of these ethnically-based deportations occurred during the Second World War (specifically between 1943-1944) when the Soviet Union used concern over German collaborators to deport almost 2 million people total from several ethnic groups including the Crimean Tatars, Chechens, Ingush, Balkars, Karachay, Kalmyks, Meskhetian Turks, and Volga Germans. In addition to these groups, Soviet authorities pursued a policy of deporting natives from land that they took over including Finns, Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, and Romanians.

While the Soviet authorities justify their actions on the basis of national security concerns, many historians today argue that the deportations were meant to displace or even liquidate what Stalin considered to be dangerous national identities and to speed the creation of a new, homogenous Soviet identity.

While these deportations were many, with each carrying its own tragic story, this article will focus particularly on the case of the Chechens/Ingush.

Deportation and Life in Exile for the Chechens and Ingush

Prior to their deportation in 1944, the Chechen and Ingush were grouped together in the Checheno-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR). While being two separate and distinctive ethnic groups, the Chechen and Ingush were considered one people by the early Soviets and labeled as vainakh (вайнах) or nakh (нах), meaning “our people,” in both Chechen and Ingush.

Throughout the entirety of Russian rule over the North Caucasus, the Chechens have had a history of uprisings against the Russian authorities. This continued into the Soviet era, with Soviet authorities struggling to implement collectivization and other policies in the mountainous region where they were met with resistance both from guerrilla fighters and ordinary people. Given this opposition, the Soviet authorities came to frequently reference their “Chechen problem.” Although less famously, the Ingush were also fiercely independent as a group and resisted Russian rule from the first Russian incursions into their homeland.

The Chechens and Ingush were eventually accused of collaborating with the Germans and singled out for collective deportation. Numerous historians, however, have argued that any collaboration, if it existed at all, was likely minimal as the Germans never made real gains in the Checheno-Ingush ASSR and most Chechen and Ingush resistance had always been opposed to any outside rule, regardless of whether it was German, Soviet, or from any other entity.

Based on the accusation, in 1944, Lavrentiy Beria, then the head of the NKVD, signed the order for deportation. On February 23rd, 1944, Operation Chechevitsa, as the authorities called the deportation efforts, began, and Chechens and Ingush were systematically rounded up and brought to railroad stations.

Many facts surrounding the deportation are disputed depending on who is writing the history. Most admit that NKVD soldiers were under orders to shoot anyone unfit to travel, and did so with many elderly people killed. Other, more dramatic events are more disputed. For instance, in the village of Khaibakh, many eyewitnesses recall the execution of an entire village. There, according to these eyewitnesses, some 700 villagers were locked in a barn which was then set on fire. Russia officially disputes that this incident happened.

Deportees were officially allowed to bring about 500 kilograms of personal items (~1,100 lbs) per family and were loaded into cattle cars. The trip itself would prove fatal for many people as the crowded cattle cars had little air, no heating, and food and water was given infrequently. The trip lasted almost a month with thousands of deportees dying from exposure, hunger, and disease. In total, some 300,000 Chechens and 90,000 Ingush were deported, with the majority bound for Kazakhstan (Kazakh SSR), although some were also transported to Kyrgyzstan (Kyrgyz SSR) and other Central Asian republics.

The belongings deportees left behind were confiscated, including livestock, homes, and lands. These were then given to others, often settlers of Russian or other Soviet ethnic backgrounds, brought in to repopulate the area. The Checheno-Ingush ASSR was officially dissolved, its lands divided between the neighboring regions.

Local authorities sought to destroy any remaining marks of the deported people with sites of cultural and ethnic importance, including cemeteries, taken apart. The NKVD continued to seek out Chechens and Ingush throughout the Caucasus and Russia, with all those found being immediately deported as well. Similarly, Chechen and Ingush soldiers in the Red Army were brought back from the front and deported.

For the Chechens and Ingush in Central Asia, the situation was dire. Local authorities were not prepared for the deportees and shortages of housing and food were common. These deportees were also designated as “special settlers,” meaning that while they were not in concentration camps of any sort, they were required to check in monthly with local authorities and prevented from leaving. Those who tried to escape were sent to Siberia.

Their lives in Central Asia were also heavily tainted by the designation of “traitor nation.” They were often chosen for the hardest building and labor tasks. Local authorities could not speak Chechen or Ingush, and the Chechen and Ingush cultures and languages were suppressed with an increased emphasis on Russian.

Today there are numerous estimates of how many Chechens and Ingush died during this period, but most agree that about 100,000 Chechens (~30% of the total population) and 20-30,000 Ingush died (~20% of the total population).

After the death of Stalin in 1953, Nikita Khruschev eventually condemned the deportations and allowed the Chechens and Ingush to return in 1957. The Chechens and Ingush would be among the lucky ones as some, notably the Crimean Tatars, were prevented from returning to their homeland for many more years. The Checheno-Ingush ASSR was also reconstituted at this time.

The problems for these two ethnic groups were far from over, however. While they were allowed to return to their homelands, their actual homes were now occupied by others. Ethnic conflicts erupted between the returning Chechen and Ingush and the new occupants. With Soviet law siding against them in these disputes, the returning deportees were forced to start completely anew yet again, often on marginal lands or taking new jobs in cities.

Commemorating the Chechen and Ingush Deportation

The Chechens and Ingush mark their Day of Grief and Remembrance on February 23rd, the day the deportation began for both groups. This date causes some discomfort for both Russian and local authorities as February 23rd is also Russia’s Day of the Defender of the Fatherland (День защитника Отечества), a Soviet era celebration that marks the creation of the Soviet armed forces (which were involved in enforcing the deportation orders) and celebrates Soviet and Russian soldiers.

In Chechnya, for eight years, between 2012 and 2020, the commemoration date was moved from February 23rd to May 10th to coincide with the day Akhmad Kadyrov, former leader of Chechnya and the father of the current leader Ramzan Kadyrov, was buried. The move, however, was never particularly popular. The remembrance date has since returned to February 23rd and, in fact, many Chechens kept marking that day even during the time that the official celebrations were moved.

Both Chechens and Ingush gather on their commemoration day to pray in mosques, visit cemeteries and, following Islamic tradition, give money and meat in charity. Some Chechens will also leave the gates to their homes open, which is commonly done by Chechen families in mourning.

Official celebrations on this date balance recognizing the Russian and Soviet forces and commemorating the victims of the Soviet deportation. The deportation ceremonies in both republics revolve around monuments dedicated to the victims.

In the Ingush city of Nazran, a large memorial complex known as “Nine Towers” (ing. Ийс гӏала, rus. Девять Башен) was opened on the anniversary of the deportation in 1997. The nine towers represent the nine major Ingush clans or teip (ing. тайпа, rus. тайп/тейп) and each is done in a different style, representing the different eras of Ingush history. The monument is bound by barbed wire and chains to represent the suffering of the Ingush. This memorial complex also contains a museum which has exhibitions illustrating the deportation as well as, interestingly, markers for prominent Ingush and local police forces who died in the line of service.

At the base of the Nine Towers monument is a collection of headstones. After the deportation of the Ingush, their cemeteries were destroyed and the headstones were taken from graves and used in construction. After the Ingush returned, as it was no longer possible to tell from what graves the stones were taken, but they found and gathered up many of these headstones and created both formal and informal memorials to the deportation using them.

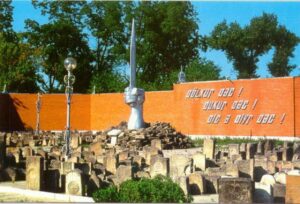

Chechnya’s Memorial to the Victims of the 1944 Deportation (che. 1944 шарахь дIабохийначеран хIоллам, rus. Мемориал жертвам депортации 1944 года) was opened in Grozny in 1992. It also prominently used headstones that were taken from cemeteries and later reclaimed. Rising above them was an arm holding a dagger. The wall behind the arm and stones was inscribed with “Dölxur dats! Duxur dats! Dits a diyr dats,” which, in Chechen, means: “We will not cry! We will not forget! We will not forgive!” However, the monument was dismantled in 2008 with prominent headstones moved to the memorial for the late Akhmad Kadyrov.

Conclusion

Operating within a complex social and political present, the Chechens and Ingush have both worked towards preserving the memories of their ancestors who perished or suffered in the Soviet deportations.

You Might Also Like

Armenian Holidays 2026: A Complete Guide

Through these holidays, you will find Armenia is filled with a rich history revolving around nationhood, family, and religious tradition. Many holidays are particularly associated with specific monuments emphasizing the importance of place in Armenian culture. Some are ancient holidays steeped in pagan symbolism, officially repressed under the Soviets, but now newly embraced by the […]

Georgian Holidays 2026: A Complete Guide

Georgian holidays strongly reflect the country’s unique traditions and its demographics. First, as more than 80% of Georgians identify with the Georgian Orthodox Church, the strong influence of the church can be felt in the preponderance of Orthodox holidays. Georgia also has several holidays celebrating its statehood and independence, which have been hard-won. We can […]

The SRAS Guide to Fermented Milk

Russia and Central Asia offer what can seem to be a bewildering selection of dairy products in their transnational food cultures. An area of special note, and often one of the strangest to Westerners, is the seemingly never-ending assortment of fermented milk drinks and products in the gastronomic repertoire. To cut down on the brow-furrowing […]

Georgia’s Story of Identity: Heroes, Memory, and Meaning

What shapes Georgian national identity? The answer is complex and personal, but one key element is the Georgian national narrative. This includes the heroes and pivotal events taught in schools, the places central to the nation’s collective memory, and the language and beliefs that frame its worldview. A national narrative goes beyond history: it is […]

Armenian Talking Phrasebook

The Talking Phrasebook Series presents useful phrases and words in side-by-side translation and with audio files specifically geared to help students work on listening skills and pronunciation. Below, you will find several useful phrases and words. To the left is the English and to the above right is an English transliteration of the Armenian translation. […]