What shapes Georgian national identity? The answer is complex and personal, but one key element is the Georgian national narrative. This includes the heroes and pivotal events taught in schools, the places central to the nation’s collective memory, and the language and beliefs that frame its worldview.

A national narrative goes beyond history: it is the people, events, places, and values that define how a nation understands itself. It lives in literature, film, and art, in monuments and place names, and in the calls to action used by leaders and activists.

This resource presents Georgia’s national narrative in a concise, accessible way to help outsiders, such as tourists, students, and diplomats, grasp the cultural foundations of Georgian society and better understand the Georgian nation.

Special Themes in Georgian Identity

Georgia is 87% ethnically Georgian; 80-86% of Georgians identify with the Georgian Orthodox Church.

Fatherland, language, and faith is a triad formed by Ilia Chavchavadze, who is considered the father of modern Georgia. It forms the core of how most Georgians define their identity. Defense of the sovereign Georgian state is coupled with an obligation to preserve Georgian culture with a focus on speaking the Georgian language and observing the Georgian Orthodox faith.

The Georgian Orthodox Church counts 80-86% of Georgians as adherents (depending on who is running the survey). Founded over 1600 years ago, the church has served as a major source of national and social cohesion and has survived hundreds of years of occupational forces that stood against it. Catholicos-Patriarch Ilia II has led the church since 1977. He is by far Georgia’s most trusted public figure, with a 90% approval rating. Churches and monasteries dot Georgians cities and into the far reaches of its isolated mountain regions. Georgians’ pride in their church has also kept the culture socially conservative.

Sakartvelo and Kartveli are the names that Georgians use to refer to their homeland and themselves, respectively. Georgians accept the exonym “Georgians,” which likely came from the Persian “Gorgistan,” meaning “land of wolves.” Invoking the endonym Sakartvelo, meaning “Land of the Kartveli” invokes a deep sense of ingroup belonging and patriotism.

The Georgian Language is part of the Kartvelian language family, which is unrelated to any other. With only 4-5 million speakers worldwide, and with the majority inside Georgia, this language family has survived thanks to the geographic isolation of much of Georgia’s territory and the extreme importance Georgian identity places on language.

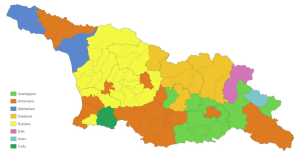

Ethnic subgroups are numerous within the Georgian identity. While Georgian is spoken by the majority of the population, many dialects and languages exist within the Kvartvelian language family. For instance, the Megrelians, Svans, and Laz have their own languages while the Gurians and Kakhetians speak their own dialects. The Adjarians are particularly unique in being traditionally Muslim in addition to speaking their own dialect. There are at least 17 such groups that all consider themselves Georgian.

European heritage is part of Georgian identity. Georgians traded with the ancient Greeks and Romans, participated in their philosophical discussions and were early converts to and defenders of Christianity. Although ruled for much of existence by empires that regarded the “West” as their antithesis, Georgians have continued to identify with Western Europe and, today, the vast majority support Georgia’s proposed integration with the EU.

Honor and hospitality are common themes in Georgian culture. These are personified in the Mother of Georgia monument in Tbilisi, who holds a sword in one hand to greet enemies, and a bowl of wine in the other to greet friends.

Georgian cuisine draws from rich local ecological diversity and equally rich Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Turkic influences. Meals are traditionally consumed slowly and meant to be community building exercises with family and/or friends, similar to Italian and French traditions. On special occasions, a supra is held, a feast that can last for hours with the main feature being a series of toasts led by a tamada, or master of ceremonies. Wine is the pride of Georgia and plays a large role in the economy and culture. Georgia may have invented it, with archeological evidence of wine production dating back to 6000 B.C.

Geography and Place

Georgia is a small but strategically important country in the South Caucasus, bordered by the Black Sea to the west and the Greater and Lesser Caucasus Mountains to the north and south. Its rugged terrain creates natural barriers that have preserved unique languages and cultures, while also complicating communication and development. Situated between Europe and Asia, Georgia has long been a channel for trade and cultural exchange, but also a battleground for competing empires seeking geopolitical advantage.

The Caucasus Mountains have shaped nearly every aspect of Georgian culture and history. Rising from the subtropical Black Sea to glacier-capped peaks 3.5 miles high, these rugged mountains create a series of microclimates supporting rich ecological and agricultural diversity. The Caucasus are also a resource-rich natural barrier, which has historically made them a strategic prize for empires seeking to dominate the region. However, their rugged terrain has also made them difficult for invaders to fully control. This has allowed Georgian culture and identity to survive centuries of occupation.

The Black Sea Coast has long been Georgia’s face toward Europe and the world beyond. Colchis, the first Georgian polity, thrived on its fertile shores, where Georgians traded with the ancient Greeks. From the 1st century BC through the 8th century AD, the area was part of the Roman empire. Pontic Greeks still reside in Batumi and Roman fortresses can be found in Adjara. The coast is also growing in geopolitical importance as its ports are a major link in the “Middle Corridor” connecting the rest of the Caucasus, the energy-rich Caspian, and even China to Europe in a route bypassing Russia. In modern times, it has become a global tourist spot dotted with resorts. Much of this activity is concentrated in Batumi, now Georgia’s second largest city. Billions are also being invested into a new deep water port in nearby Anaklia to boost capacity. About half of Georgia’s Black Sea coastline lies in Abkhazia, a region that broke away from Georgia in the early 1990s (see below).

Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital and by far its largest city, accounts for about 33% of the state’s population and 50% of its GDP. Its diverse architecture reflects its experience under Persian, Russian, Soviet, Turkic, and Georgian rulership. The 5th-century Sioni Cathedral dates from around the city’s founding while the 16th century canvasarai reflects its long history as a trading hub. The 20th-century Sameba Cathedral was built post-independence to celebrate a new era of nation building. Its history is also reflected in the synagogues and mosques, as well as its cosmopolitan population that includes Jews, Armenians, and Azerbaijanis. Home to prestigious museums, educational institutions, and a vibrant arts scene, Tbilisi represents both Georgia’s proud past and its modern economic and social opportunities.

Cave cities showcase Georgia’s ancient civilization, resilience, and Christian heritage. Painstakingly hewn into mountain rock, these settlements were built for permanence and defense. Uplistsikhe, dating from the first century, was a prominent pre-Christian political and religious center. Later a Silk Road trading post and wartime refuge, it was abandoned only after the 13th-century Mongol invasion. David Gareja Monastery, founded in the 6th century, eventually expanded to 5000 monastic cells and related infrastructure. Vardzia, begun as a fortress in the 12th century, gained a palace, monastery, well, and housing for 10,000 under Queen Tamar. It was used to stage armies and safeguard Georgian treasures. Damaged by an earthquake in 1283, it was abandoned in 1578 after successive Persian and Ottoman attacks. Today, it is a popular museum-reserve and the monastery has been reopened.

Svaneti and Tusheti are known for their unique defensive towers that doubled as homes. These regions are the homelands of Georgian ethnic subgroups known for warrior traditions.

Kakheti is an eastern region. Its arid and mid-subtropical climates produce a majority of Georgia’s economically and culturally important wine output. The annual Rtveli festival draws thousands of Georgian and foreign tourists to celebrate the autumn grape harvest. Kakheti is home to the Monastery of St. Nino at Bodbe, where the relics of St. Nino, who called the region home, are housed. The sixth-century David Gareja Monastery, one of Georgia’s oldest monasteries, is also located in Kakheti.

Kutaisi, settled in the 6th century BC, is one of the oldest continually-inhabited cities in the world. It served as the capital of both ancient Colchis and the unified Kingdom of Georgia as it entered its Golden Age. The city is home to Bagrati Cathedral and Gelati Monastery, a flagship project of David the Builder and one of the earliest academies in Europe.

Mtskheta is the historical center of the Georgian Orthodox Church. The capital of the Kingdom of Iberia from the second to the fifth century AD, it houses such important structures as the Samtavro Convent, the Jvari Monastery, and the sacred Svetitskhoveli Cathedral, known as the birthplace of the Church and final resting place for many Georgian monarchs.

Historical Heroes

The following people have played pivotal roles in Georgian history. Many of the below have monuments to them and places named for them in Georgia. They generally appear as heroes in textbook histories of Georgia in Georgian schools.

King Pharnavaz I created the first Georgian state by unifying the Georgian tribes in the 3rd century BC. He is also often credited with creating the Georgian alphabet.

Saint Nino converted the Georgian queen and king in the early 4th century, making Georgia one of the world’s earliest Christian states. Her hagiography tells us that she began preaching and performing miracles after a vision of the Virgin Mary told her to do so. Mary is said to have given Nino the inspiration for her trademark cross, made of grapevines bound with Nino’s own hair. Having heard of Nino’s gifts, Queen Nana, severely ill, sent for her. After a miraculous recovery, she converted and pressured her husband, King Mirian III, to do the same. Mirian, likely after seeing a total eclipse (which scientists have dated to May 6th, 319 AD), also converted. The three are known as the apostles of Georgia, and Saint Nino’s grapevine cross is an ever-present symbol of Georgian Christianity.

King Vakhtang I Gorgasali was a fifth century warrior king who founded Tbilisi. Although the Persian Empire conquered Georgia during his reign, his battles against them are legendary examples of the Georgian will to fight for homeland and faith no matter the adversary’s strength.

King David IV “the Builder” kicked off the Georgian Golden Age in the late 11th century. He expelled the Seljuks in the Battle of Didgori, still considered Georgia’s greatest military victory. This restored Georgia’s independence and began a period of Georgian military expansion. David strengthened his empire with civil, economic, and religious reforms, fostering Georgian identity by founding schools, monasteries, and churches. His most enduring landmark, Gelati Monastery, near the former capital of Kutaisi, became a renowned center for both religious and scientific learning and remains standing today as a prime example of medieval Georgian architecture. David was declared a saint by the Georgian Orthodox Church and remains one of the most respected rulers in Georgian history.

Queen Tamar “the Great” led Georgia to the height of its Golden Age started a century before by her great-grandfather, King David IV. Named co-ruler by her father, she was able to sidestep the unwritten rule that the throne be passed only to a male heir. After successfully defending her position against detractors, she greatly expanded Georgian territory. She fought and won the Battle of Basian, crushing the Seljuk Sultanate of Rüm and solidifying Georgia’s regional dominance. She built alliances with Byzanitum and Europe, positioning Georgia as a bulwark against Muslim conquests and an ally in the Crusades. Queen Tamar was also a prolific patron of the arts and today is one of the most beloved Georgian monarchs.

Shota Rustaveli wrote The Knight in the Panther Skin, Georgia’s national epic poem, while a member of Queen Tamar’s court in the early 13th century.

Ilia Chavchavadze is the father of modern Georgia. A 19th-century writer, journalist, financier, and activist, he used his family wealth to promote Georgian literacy, publications, property ownership, and independence while under Russian imperial domination. His coined triad “Fatherland, Language, and Faith” is regarded as largely definitive of what it means to be Georgian. He is remembered as a literary genius and visionary leader whose writings, ideas, and actions inspired a national awakening, laying the groundwork for the Georgian Democratic Republic of 1917-1920 and the current Georgian state. Chavchavadze was assassinated in 1907 and, while his assailants were found and hanged, it is unclear if the assassination was ordered and, if so, by whom. He was declared a saint by the Georgian Church in 1987.

Niko Pirosmani was a self-taught painter known for his depictions of everyday Georgian life at the turn of the 20th century. He remained unknown in his lifetime, a former peasant and manual laborer who lived in poverty. Only after his death was his collection discovered and raised up as a national treasure for its distinctive “naive” style and depictions of Georgian daily life. His paintings hang in the national museum and are often recreated as murals to create an instantly recognizable Georgian atmosphere.

Zviad Gamsakhurdia, Georgia’s first modern president, was dissident and human rights defender who was imprisoned and exiled several times during the Soviet era. In the 1980s, he became an iconic leader of the Georgian liberation movement. He is remembered by the vast majority of Georgians as an intellectual and patriotic leader. He was overthrown in a coup just seven months into his term, which further destabilized Georgia and was followed by a civil war and armed conflicts with the Ossetians and Abkhazians. Debate surrounding him focuses mostly on if he could have done more to prevent the economic and political problems that followed his short term in office. He is buried in the prestigious Mtatsminda National Pantheon in Tbilisi.

Historical Events

The following events have shaped Georgian cultural identity and continue to resonate in Georgian life today. Rather than simple historical milestones, these moments represent turning points in how Georgians understand themselves and their place in the world. Read a full history from our sister site at GeoHistory here.

The Christianization of Georgia supplanted numerous earlier religious traditions like Georgian polytheism, Zoroastrianism, Hellenistic cults, and Roman Mithraism. King Mirian III’s conversion in 326 by young St. Nino made Georgia one of the first Christian states. Georgia became an important contributor to the early intellectual and artistic Christian world. Georgia was also opened to Byzantine influence, which would play an important role in early Georgian state and culture formation. Georgian Orthodoxy set Georgians apart from their later Islamic and Soviet-atheist imperial occupiers, helping to protect Georgian identity from assimilation. It remains central to Georgian identity today.

The Georgian Golden Age lasted from the late 11th century through the mid 13th century. In 1089, King David the Builder came to power, expelled the occupying Turks, and established Georgia as an independent state. His various reforms and development of prosperous trade routes led to a flourishing of civil life and education, art, and culture. At its height under Queen Tamar, the kingdom and its vassals stretched across the South Caucasus, from the Caspian Sea and encircling much of the Black Sea. Internationally, Georgia was recognized as a strong European Christian ally when Islam loomed large at Georgia’s and Europe’s doorstep. The Golden Age ended with what are often seen by Georgians as inescapable forces: decades of Mongol invasions and waves of bubonic plague followed by renewed encroachment by the Persians and Ottomans.

The Democratic Republic of Georgia, founded in 1918, is widely regarded as the precursor to modern Georgia. In the late 19th century, the Georgian national movement, through authors such as Ilia Chavchavadze and Akaki Tsereteli, advocated for autonomy from the Russian Empire. After that empire collapsed in 1917, the Democratic Republic of Georgia was founded by Georgian Mensheviks, who emphasized progressive ideals of democracy through education and equal rights. The republic ended following the Bolshevik invasion of 1921. However, when Georgia regained independence in 1991, continuity with the Republic’s ideals was emphasized, implying that Georgia was not a new state, but rather one reconstituted after a period of occupation. The republic’s flag and coat of arms were initially reinstated although later revised in 2004. This encouraged patriotism for the new state by feeding into a major element of the national narrative: that Georgia is fundamentally sovereign and, if under occupation, need only maintain its culture and wait for the next inevitable manifestation of independence.

Soviet Georgia plays contradictory roles in Georgian identity. Although the Democratic Republic was taken by force, not all Georgians opposed the move. While most agree to the fact that Stalin’s purges were horrific, some still regard Stalin with respect and affection, particularly in his hometown of Gori, where a museum, supported by the Georgian state, presents a positive picture of him. Many Georgians fought for independence, including those who gave their lives and are now honored with a national holiday. However, only in 2024 did a majority of Georgians agree that the dissolution of the USSR was good. Even today, many argue that life was economically better under the USSR, when industry and tourism were heavily patronized and subsidized by the state. With the Soviet collapse, that support collapsed, taking much of the economy with it. Georgia has since struggled to unify politically and, to this day, struggles to fully recover economically. Thus, while many find reason to rejoice in independence, others find reason to mourn the loss of political stability and relative prosperity.

Wars Post-Independence have created national trauma that now heavily influences identity as well as modern social and political life. From 1991-1993, Georgia endured civil and secessionist wars. It was left divided politically and fragmented geographically, with two breakaway republics closing their borders to the rest of Georgia. Many were killed or displaced and families were broken apart. In 2008, the separatist conflict again flared up with Russia again backing the South Ossetian separatists. This sparked the Russo-Georgian War, which resulted in a crushing defeat for the Georgian army. Nearly every Georgian family was deeply and personally impacted by these wars and today, reintegrating the lost territories is the most pressing social and political issue according to Georgians. Improving the economy, which has also been negatively impacted by these divisions, ranks as number two.

Diversity

Of course, not everyone in Georgia is Georgian. The stories and experiences of a country’s ethnic minorities are also part of the lived experience that defines it as a state. Georgia’s last census was taken in 2014, so many of the numbers here may be somewhat outdated. The Georgian ethnicity consists of several sub-ethnic groups that are not included here.

South Caucasian ethnicities (ie Azerbaijanis, Armenians, and Georgians) have historically lived together. Continual movement and mixing was alternately forced by war or encouraged by peacetime economic opportunities. When Russia took over in 1801, for instance, Tbilisi’s ruling class was Georgian, but the population was majority Armenian and the city had more mosques than churches after centuries under Islamic rule. Only under Russian and Soviet control did nationalities consolidate within fixed borders.

Azerbaijanis are Georgia’s largest minority, at approximately 6% of the population. They are mostly concentrated in Georgia’s east, which borders Azerbaijan. There is a particular concentration in the lightly populated Kvemo Kartli Region, where they make up 42% of the population. Azerbaijanis in Georgia have historically had difficulty integrating as most do not speak Georgian, are Muslim, and keep within insular communities. The Kvemo Kartli Region is economically poor and many Georgians blame the government for not investing more in the region’s economy and educational opportunities to encourage greater integration.

Armenians account for about 4% of Georgia’s population. They have largely concentrated in urban areas where they have traditionally been merchants and craftsmen. The Armenian heritage of Tbilisi can be seen around the city, including the house of the merchant Melik-Azaryants on Rustaveli Avenue and the many Armenian churches in the historically Armenian Avlabari District. Notable Armenians in Georgia have included the novelist Raffi, the poet Hovhaness Tumanyan, and the Soviet filmmaker Sergei Pajaranov, among many others. The Samtskhe-Javakheti Region, which borders Armenia, is approximately 50% Armenian.

Georgian Jews likely first arrived in Georgia in the 6th century B.C. after Nebuchadnezzar’s conquest of Jerusalem in 586 B.C. Georgian Jews historically have spoken Qivruli, a Kartvelian language heavily influenced by Hebrew. Today, there are only about 1500 Georgian Jews in Georgia and Qivruli is increasingly endangered. Most Georgian Jews emigrated to Israel or western countries under the USSR or just after it fell.

Russians gained a noticeable presence in Georgia after conquering it in the 19th century, eventually making up about 10% of the population under the USSR. After 1991, the Russian population fell to a bit less than 1%. However, when Russia’s military mobilization began in 2022, over 110,000 Russians surged into Georgia, largely to avoid conscription. That would represent a boost to Georgia’s population of nearly 3%. Since then, more Russians have arrived but many have moved on or returned to Russia. Estimates of how many Russians may be in Georgia today range from 30,000 to 200,000. Georgia has played a large role in Russian culture, with many Russian authors such as Alexander Pushkin, Leo Tolstoy, Boris Pasternak, Mikhail Lermontov, and Vladimir Mayakovsky having lived or had their careers impacted by experiences in Georgia. Russians in Georgia are concentrated in major urban centers such as Tbilisi and Batumi, which also remain popular destinations for Russian tourists.

Assyrians first arrived in the 6th century as Christians seeking refuge in Georgia’s Christian state. The most prominent were the Thirteen Assyrian Fathers, who founded numerous monasteries including David Gareja. Today, the Assyrian community is small but known, and the Georgian Orthodox Church has aided in preserving their native Aramaic language. Official support has been extended to Father Seraphim Bit-karibi, for instance, who is known internationally for his Aramaic chanting.

Breakaway Regions

Georgia has two breakaway regions which account for 18% of the country’s internationally recognized territory. Both regions fought secessionist wars against Tbilisi in the early 1990s. Both were historically part of Georgia and its national psyche. Georgians largely see these traumatic conflicts as having been engineered and perpetuated by Russia. Both territories are recognized by the international community at large as part of Georgia notwithstanding the presence of de facto local authorities, the Russian military occupying both regions, and the majority of both regions’ populations being Russian citizens. Nearly all Georgians consider reintegrating these territories a critical national priority – with many prioritizing it even above improving the economy. Because this issue is complex and so important to understanding modern Georgia, we consider it in this separate section.

Visitors to Georgia should keep in mind that discussing these conflicts with locals, particularly ethnic Georgians, can be extremely sensitive as passions run very high on these issues.

Abkhazia

Abkhazia—Apsny in Abkhaz, apkhazeti in Georgian—is located along the Greater Caucasus and the Black Sea. The Abkhaz speak a Northwestern Caucasian language. Their unification with the Kingdom of Georgia in 989 is historically seen as a bedrock in the consolidation of Georgia’s political traditions, eventually allowing it to declare independence from the Seljuk Sultanate and rise to its Golden Age. Many Christianized Abkhaz entered the Georgian nobility, many adopted Orthodox Christianity (while retaining pagan traditions), and intermarried widely with Mingrelians. After the 19th-century Russian conquest of Georgia, Abkhazia’s remaining Muslims and pagans, who had hitherto constituted the region’s majority, were largely expelled to the Ottoman Empire and, over time, replaced with mostly Christians from a range of ethnicities.

The Soviets declared Abkhazia an Autonomous Republic within Georgia in 1931. Political purges curtailed Abkhaz autonomy. Mingrelians were favored for key administrative roles. Soviet Abkhazia was actively developed, becoming an agricultural hub producing tea, tobacco, citrus, and other cash crops, and a premier resort area for party elites and tourists—Stalin himself kept five dachas there. Although cultural policies initially favored Georgianization, Russification, particularly in language, was favored after Stalin’s death. Russian became the lingua franca, drawing Georgian protests.

By the late Soviet period, the Abkhaz accounted for less than a fifth of Abkhazia’s population. Perestroika-era debates on the cultural, linguistic, and political rights of the Abkhaz eventually devolved to ethnic conflict. Supported by Russia, Abkhazia became de facto independent after the 1992–1993 civil war. Georgians and Abkhaz, who had coexisted for centuries, were largely displaced to their separate sides of the borders. Georgian refugees were so numerous they overwhelmed many areas of Georgia that they relocated to. Many still live in squalid conditions.

Today, out of about 240,000 residents in Abkhazia, the Abkhaz form a narrow official majority, bolstered by returning decedents of groups formerly expelled to the Ottoman Empire. Georgian language use is heavily restricted. Less than 1000 Abkhaz now live in Tbilisi-controlled areas, mostly concentrated in Batumi and Tbilisi. Russia has heavily supported the region with development funds, including revitalizing some Soviet-era resorts, offering expedited citizenship to most Abkhaz residents, and maintaining a large military presence. Basing some of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in Abkhaz ports is currently under consideration.

Abkhazia is recognized internationally as part of Georgia.

South Ossetia

South Ossetia is a breakaway region in northern Georgia, known in Georgian as Samachablo or the Tskhinvali District. The Ossetians refer to the region as Ossetia or Alania. Ossetians speak an Eastern Iranic language related to that of the ancient Scythians and Alans.

Christianity reached the Ossetians in the Middle Ages, but never became deeply rooted. The largest Ossetian migration to Georgia from their former homelands in the North Caucasus occurred in the 17th century, when most became peasants working for Georgian noble families such as the Machabelis (Samachablo means “land of the Machabelis” in Georgian). During the period of Georgia’s independence in 1918-1920, conflict brewed between the Bolshevik-leaning Ossetians and the Menshevik-leaning Georgians that led Georgia’s government at the time. It eventually erupted into violence and mass atrocities on both sides.

After the 1921 Bolshevik invasion of Georgia, Moscow created the South Ossetia Autonomous Oblast within the Georgian SSR. The region had an Ossetian majority but no prior Ossetian political structures. Ossetians gradually consolidated their presence there, particularly in urban areas like Tskhinvali, which had historically been a culturally Georgian city. Under Stalin, policies tried to assimilate the Ossetians with the Georgians. After Stalin, Russification policies became dominant, although the promotion of Russian as a lingua-franca was not as effective as in other regions.

As Soviet rule in Georgia weakened and fell, Georgians increasingly questioned the oblast’s Soviet-established autonomy. This conflict erupted in a civil war in the early 1990s. With Russian support, South Ossetia won de facto independence but almost no international recognition. Russia supported the region with aid and offered expedited Russian citizenship for Ossetians. This frozen conflict erupted in war again in August 2008, with Russia supporting the Ossetians again, who again maintained their independence and were then recognized by Russia and a handful of small countries as independent.

Before the wars, about 164,000 South Ossetians lived in Georgia. Today, the region’s population is now officially around 56,000, although its likely closer to 35,000 in reality. According to a recent census, some 15,000 Ossetians still live in Tbilisi-controlled territory, although many do not openly identify as Ossetians to avoid discrimination. Many Ossetians migrated to Russia due to the conflict.

South Ossetia is recognized internationally as part of Georgia.

You’ll Also Love

The Monastery of Saint Nino at Bodbe in Georgia

During my first week in Georgia, my classmates and I took a trip out to Sighnaghi, which is roughly a two-hour drive from Tbilisi, the Georgian capital. In Sighnaghi, we visited the Monastery of Saint Nino at Bodbe, which was built in the 9th century and renovated extensively in the 17th century. Saint Nino, who […]

Chichilaki and Alilo: Georgia’s Unique Celebrations of Christmas

Georgia’s Christmas traditions of chichilaki and alilo reflect the deeprooted importance of tradition, sustainability, and religious expression in Georgian culture. Chichilaki are a unique, eco-friendly alternative to the Christmas tree that have been present in Georgian culture since ancient times. Meanwhile, alilo is a caroling tradition when costumed Georgian take to streets to sing religious […]

Georgian Nutrition: A Tasty Way to Good Health

As a nutritionist, food is often the driving factor of my travels. I love exploring the local and traditional cuisines which help shape the identity of a country. Georgian culture is strongly influenced by, and perhaps best known for, its unique and vibrant cuisine. Georgian cuisine in Georgia is packed with fresh and organic produce […]

Podcast: What Makes Georgian Food Georgian?

What makes Georgian food Georgian? How does the development of Georgian cuisine reflect historical events, geography, and politics? Where do you find the best food in Georgia? In this podcast, Dr. Michael Denner, professor of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies at Stetson University, discusses traditional Georgian foodways, answering these questions and more. Dr. Denner […]

Berikaoba: Georgia’s Spring Festival Rises Again

Berikaoba is defined by its monstrous-looking masks, good-natured pranking, games and performances of strength, freely shared food and wine, and general festive atmosphere. Although the festival was nearly lost to the passage of time, locals, foreigners, and Georgians from other corners of the country now flock to the Kakhetian villages of Didi Chailuri and Patara […]