Estonia’s calendar is filled with holidays that make for an excellent introduction to its history, culture, and national values.

Many, many holidays and observances mark Estonia’s struggle for independence, including the dates of key battles, declarations, and treaties. This is unsurprising for a nation that has enjoyed only a few decades of independence since the early 13th century. Other holidays celebrate Estonia’s pre-occupation heritage, which is rooted in pagan traditions. As one of the world’s least religious countries, pagan and religious elements of Estonian culture are now seen as secular expressions of national identity. Estonians celebrate a majority of their holidays by simply retreating to nature—whether hiking, staying at a suvemaja (a summer home similar to the Russian dacha), or, for big celebrations, gathering around a bonfire with food, drink, and family.

Days Off

Long Weekends and Extra Days Off by Semester for 2026

| Spring | Summer | Fall | Winter |

| April 3-5 May 1, 24 |

June 23-24 August 20 |

January 1 February 24 December 24-26 |

New Year’s Day

In Estonian: Uusaasta

January 1, 2026

(day off: January 1. December 31 is a shorter working day)

In Estonia, New Year’s stems from winter solstice celebrations. Today, Christmas is the main focus of the winter holidays, with New Year sharing much of its symbolism. The new year is enthusiastically celebrated in Estonia with many associated traditions.

Larger cities have firework displays and concerts around crowded main squares. The main celebrations in Tallinn are also typically televised for the majority of the population that celebrates at home or at country homes, eating, drinking, and socializing with friends and family. Escaping to the countryside is especially valued by many. Optimally, one can sit in the sauna and take ice plunges, an ancient tradition believed to wash away the old year and prepare you for the new.

The TV will often be on, playing in background, at such gatherings. The Estonian TV series Õnne 13 (a drama running since 1993) will have a special New Year’s episode. Alternative staples are Mr Bean reruns, the classic comedy Dinner for One, and The Old and Frail Get Their Feet Wet (Vanad ja kobedad saavad jalad alla), one of Estonia’s most popular and successful movies ever.

Traditional New Year’s meals closely mimic Christmas dishes and include items like pork, sauerkraut, lingonberry or cranberry jam, sült (meat jelly), blood sausage, and gingerbread. One additional superstition says that it is lucky to have 7, 9, or 12 dishes on the table. Each should be eaten, but none should be finished. This comes from folklore that teaches that food should be left for any visiting spirits on this day.

As in many cultures, Estonia’s new year comes with opportunities for divination. One of the most interesting is melting tin and pouring it in water in order to read the shape it makes. Small pieces of horseshoe-shaped tin are sold for this purpose. In some parts of Estonia, it is believed that if you stand at a crossroads on New Year’s, you can divine the future from the sounds you hear.

There is also much in the way of ensuring good luck for the coming year. One has to be awake, with loved ones, very full, and preferably outside when the clock strikes midnight. One’s home should be clean and any quarrels resolved. Prior to fireworks being introduced, firearms were traditionally shot into the sky at midnight to scare away evil spirits.

New Year’s Day itself is generally a day to simply relax, eat leftovers, and recover from the night before.

Anniversary of Tartu Peace Treaty

In Estonian: Tartu rahulepingu aastapäev

February 2, 2026

(Not a day off)

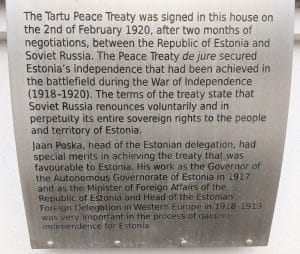

This day commemorates the 1920 Tartu Peace Treaty, in which Soviet Russia renounced all claims to Estonian territory and recognized Estonia’s right to self-determination. These terms were soon violated when the Soviet Union occupied Estonia in 1940, which was followed by a Nazi occupation and a Soviet re-occupation from 1944 to 1991.

In Tartu, the main observance is held at Vanemuine Street 35, where the treaty was signed. The Estonian flag – a central symbol of the holiday – is formally raised at sunrise and lowered at sunset during official ceremonies. Flag-related events take place at various memorials, often attended by veterans and active-duty military, honoring those who died in the fight for freedom. Schools also hold special lessons and assemblies, sometimes featuring local officials.

The legacy of Soviet occupation remains vivid in Estonian memory, and independence from Russia is a deep source of national pride. However, when Estonia regained independence in 1991, its borders did not revert to those defined by the Tartu Treaty, and some territory was ceded to Russia. A new border treaty has never been ratified, partly because Russia objected to references to the Tartu Treaty in the proposed treaty. As a result, Estonia remains the only EU country bordering Russia without a ratified border agreement.

Independence Day

In Estonian: Iseseisvuspäev, Eesti Vabariigi aaastapäev

February 24, 2026

(day off: February 24)

Estonia declared its independence from the Russian Empire on February 24, 1918. The significance of this day is considered even more relevant since the invasion of Ukraine, which happened to fall on February 24, 2022.

Estonia has numerous holidays that specifically celebrate its independence. However, this holiday is considered Estonia’s main national holiday and celebrated most energetically.

The flag and the military are the main symbols of the celebration. Flags are seen everywhere on this day and the military is the main focus. A parade staffed by the Estonian military and its NATO allies travels along Tallinn’s avenue from its national opera to Freedom Square. A significant number of NATO troops are stationed inside Estonia, as a deterrent to a potential Russian invasion. A showcase of defense equipment is held on Freedom Square, where children can climb up on transport vehicles and tourists can snap selfies with tanks. The atmosphere nowadays is both celebratory and solemn, and the day is treated with a matter-of-fact reverence typical of Estonian national pride. In other cities, small military bands and Estonian troop contingents will march through the city square and military equipment will also be on display.

The most traditional food to eat on Independence Day is classic Estonian comfort food: potato salad and a sprat sandwich. The sandwich consists of an open-face stack of hard-boiled egg, sprats, and mayonnaise on top of a slice of dark Estonian rye bread. You can find special ice cream dyed in Estonia’s national blue-black-and-white colors (flavored blueberry, chocolate, and vanilla). In pubs, similarly colored layered shots are enjoyed, poured from blue Curacao liqueur, black coffee, and whipped cream.

Mother Tongue Day

In Estonian: Emakeelpäev

March 14, 2026

(Not a day off)

Mother Tongue Day is the birthday of Kristjan Jaak Peterson, an Estonian poet from the early 19th century and considered the father of Estonian-language poetry. Prior to Peterson, most literature in Estonia was published in German or Latin. Estonians are very proud of their language’s resilience through centuries of various occupations. Cultural institutions such as libraries, schools, or universities will typically have special programs on this date, although most people don’t go out of their way to celebrate the holiday.

Good Friday, Holy Saturday, and Easter

In Estonian: Suur reede, suur laupäev ja ülestõusmispühade

April 3 2026 -April 5 2026

(days off: April 3-5 2026)

Estonia is one of Europe’s least religious countries. Although Good Friday and Easter are official holidays, most Estonians use the long weekend to relax, visit friends, or head to the countryside if the weather allows. Public institutions and some businesses close on Good Friday; nearly everything shuts down on Easter. Estonia’s small practicing Christian minority may attend services on both days, and church bells can be heard throughout the weekend.

Like in many pre-Christian cultures, Estonia had rituals for spring, fertility, and the return of longer days. Many of these became associated with Holy Week and Easter after the arrival of Christianity. Many of these remembered today are shared in common with other Eastern European cultures.

Easter eggs are dyed using natural ingredients such as onion skins or beetroot juice. Traditionally, girls would give eggs to boys as thanks for building the village swing, an important symbol of the season. The swing would typically be built on the highest hill and youth would swing as high as they could to ensure the coming harvest would be bountiful. Swinging as a fertility rite is part of many East European cultures. Today, it’s still common to eat a large lunch on Easter Sunday which features egg-centric dishes. Egg knocking contests with family members – tapping your egg against your opponent’s to see whose cracks – are widespread. The southeastern region of Setomaa hosts a special egg-rolling contest on sand ramps. Easter egg hunts typically occur on Easter Sunday, especially among families with young children.

Estonia also counts paskha, a shaped curd cheese dish made with dried fruits and nuts, as a tradition shared with Slavic cultures and Finland, for instance.

The week before Easter often involved spring cleaning, and folklore suggests its weather predicts the summer ahead; rain promised more rain while fog forecast heat.

These and other traditions exist and are generally still remembered but are irregularly practiced, particularly for those without young children.

Spring Day

In Estonian: Kevadpüha

May 1, 2026

(day off: May 1, 2026)

May 1 has a long and somewhat convoluted history. In pagan times, it was a celebration of the arrival of spring and warmer weather, but with Christianization, many of its customs became associated with Easter. In fact, its name, “Kevadpüha” which literally means “holy spring,” and is sometimes used to refer to Easter as well or to the holy week preceding Easter.

Yet Spring Day itself also remained celebrated after Christinization, often with festivals and games. During the medieval period, for instance, a large festival would be held in Tallinn where the “Count of May” would be “crowned” after proving himself at swordplay and horseback riding.

In the 19th century, St. Walpurgis Night (Volbriöö in Estonian), also celebrated on May 1, arrived in Estonia via Swedish influences. St. Walpurga was an 8th century abbess from Germanic Francia canonized for her healing powers and fight against witchcraft. According to legend, witches would gather on April 30 so bonfires were lit to drive them away. In Estonia, the tradition changed slightly and some would dress as witches to dance around the bonfires. The tradition is still observed by some in Estonia.

By the first half of the 20th century, Estonia changed May 1 to Labor Day, celebrating workers and their rights, in alignment with many other Western nations. This emphasis continued during Soviet occupation, when Communist party parades and speeches dominated the day’s festivities. After independence, Estonia reverted the name back to Spring Day, removing any association with labor or communism.

Today Spring Day has partially reverted to its roots. It is a secular holiday simply celebrating the arrival of warmer weather after a long, dark winter. On the day’s eve, bonfires are lit and plenty of food and drink consumed. Many cities will have a variety of open-air festivals, food stands, events, and fun activities scheduled for the actual day of May 1.

Europe Day/Victory Day

In Estonian: Euroopa päev

May 9, 2026

(Not a day off)

May 9 is perhaps Estonia’s most divisive holiday. As Victory Day, it marks the end of World War II. However, for many Estonians, it also symbolizes the start of the USSR’s reoccupation of Estonia. This meant the loss of their short-lived independent state and the start of decades of oppression, mass deportations, economic hardship, and executions under Stalin and his successors.

May 9 is also Europe Day, celebrating the issuance of the Schuman Declaration that would become the foundation of the EU. For many Estonians, joining the EU and NATO were two fundamental acts that advanced their prosperity and security as an independent nation after the fall of the USSR. Europe day is celebrated with a fair-like atmosphere and major cities will host concerts in the evening. EU flags dominate the scene. In Tallinn, there is a tent set up in Freedom Square which hosts tables from European embassies with information about other member states, and how to travel or even study there.

Tensions arise from the contrasting ways that most ethnic Estonians and Estonia’s Russian minority population – about 35% of Tallinn and 20% of the country – observe the day. The divide came to a head in 2007, when the Bronze Soldier, a Soviet monument to the soldiers who had pushed the Nazis from Estonia (and reclaimed it for the Soviets) was relocated from central Tallinn to the out-of-the-way Defence Forces Cemetery just a few days before May Day that year. Each year, flowers are laid at the statue on May 9 by Estonia’s Russians, to honor relatives who died in WWII. The late-night move sparked protests from local Russians and condemnation from the Russian Foreign Ministry.

Narva, a majority-Russian city on the Estonian-Russian border, is another place where modern memory politics are especially visible. Since 2022, Russia has staged Victory Day events on its side of the river so Narva residents can watch. Meanwhile, Estonia organizes Europe Day celebrations in Narva’s town square, often with concerts.

With competing narratives and heightened sensitivities, police presence increases, particularly in Tallinn and Narva. While the celebrations are kept separate and have always proceeded rather quietly, the tensions between the two populations are palpable on this day.

Flag Day

In Estonian: Eesti lipu päev

June 4, 2026

(Not a day off)

Estonians take great pride in their blue-black-white tricolor, which was banned during the Soviet occupation. Today, flags are widely displayed on homes and businesses across the country. A special ceremony marks the flag-raising at Pikk Hermann Tower in Tallinn—part of the city’s 14th-century defensive walls and located near the modern parliament in Tallinn’s historic central district. The flag was first raised there in 1918 to symbolize Estonia’s independence. While daily flag-raising and lowering ceremonies take place year-round, the Flag Day ceremony is especially elaborate.

The very first Estonian flag is still preserved and on display at the Estonian National Museum in Tartu. It spent 50 years in hiding, including being buried underneath a chimney at a farm in Jõgeva County, to prevent it from destruction by Soviet officials. A double which had replaced it among Estonian representatives in 1940 was confiscated and never to be seen again – making it all the more remarkable that the original has survived!

Pentecost

In Estonian: Nelipühade

May 24, 2026

(day off: May 24, 2026)

Like Good Friday and Easter, much of the population does not religiously celebrate Pentecost and treats it rather as a day off at the start of summer – perfect for grilling, biking, and going out with friends. Pentecost was made a public holiday in Estonia in 2005 and is reflective of the county’s experience with Lutheranism and Catholicism under German rule. It is celebrated on the seventh Sunday after Easter and is supposed to mark the time that the Holy Ghost descended on the 12 apostilles. Some, but not all, businesses close and churches will hold special services.

Day of Mourning

In Estonian: Leinapäev

June 14, 2026

(Not a day off)

This day, shared with Latvia and Lithuania, is used to recognize and remember the victims of Soviet deportations. On this date in 1941, some 10,000 Estonians were deported to Siberia and Kazakhstan, most often to labor camps. Additional deportations were carried out through 1953, eventually numbering over 35,000. Flags are flown at half-mast on this day. Speeches and wreath-layings are held at monuments such as the Memorial to the Victims of Communism in Tallinn. A temporary memorial display on the history is also typically found on Tallinn’s Freedom Square.

Victory Day/Midsummer’s Eve and

St John’s Day/Midsummer Day

In Estonian: Võidupüha and jaanipäev

June 23 – June 24, 2026

(day off: June 23 – June 24)

Victory Day and Midsummer’s Eve fall on the same day and have merged in celebration. Most businesses close for the occasion.

Victory Day (not to be confused with the other one on May 9) commemorates the 1919 Battle of Cēsis (Võnnu in Estonian), where Estonian troops, fighting alongside Latvians, decisively defeated Baltic-German forces. This ended centuries of German dominance and helped secure Estonia’s first modern independence. A military parade is held in a different Estonian city each year to celebrate, accompanied by a flag-raising at parliament. Folk dancing and outdoor festivities follow, and the president lights a ceremonial bonfire. Its flames are carried to other cities and used to ignite their own fires.

This bonfire marks the transition into Midsummer’s Eve, an ancient pagan holiday that was once one of the most important markers of the agricultural cycle. Today, it remains Estonia’s most joyous holiday. Many people head to the countryside, where bonfires mark both Estonia’s independence and the year’s shortest night. The sun sets around 10:45 p.m. and rises by 4 a.m.

Traditionally, these bonfires symbolized the triumph of light over darkness and were believed to drive away evil spirits that could harm crops. Jumping over smaller fires for luck and purification is still practiced. Large wooden swings – common in fertility rites – are popular, and staying up to greet the sunrise is essential, with even children encouraged to stay awake.

Beer and grilled meats, including sausages, are staples, accompanied by cabbage, potato salad, or tomato-cucumber salad with sour cream.

Midsummer’s Eve and Day are a time to reconnect with family, especially for those living apart. Many Estonians living abroad return home for the occasion.

Known in ancient times as leedopäev (“fire day”), the holiday was renamed Jaanipäev (John’s Day) after Estonia’s Christianization, aligning it with St. John the Baptist’s saint’s day. The date also shifted slightly from the solstice (June 20–21) to June 23. However, most Estonians see little of religion in Midsummer. Rather, it is seen as a celebration as old as the Estonian people and one that celebrates their environment, national culture, and families.

National Song and Dance Festival

In Estonian: Laulu- ja tantsupidu

First weekend of July, every five years

(Next occurance in 2030; Not a day off)

The Estonian Song and Dance Festival is held every five years. Featuring traditional Estonian songs, dances, and costumes, the significance of the festival is hard to overstate.

Originating in 1869 in Tartu during the rise of Estonian nationalism, the first festival became a landmark event in the Estonian National Awakening—a movement that shaped national identity and helped lead to Estonia’s first independence. Though closely regulated by authorities, the festival was allowed to continue through the Soviet era. Its main stage, the Song Festival Grounds in Tallinn, was built in 1959 to celebrate the Estonian SSR’s 20th anniversary. The stage holds 15,000 performers with audience seating for 100,000. In 1988, the festival defied Soviet censors by singing banned patriotic songs, helping spark the Singing Revolution and paving the way for Estonia’s second independence.

Since the 1990s, the three-day Song and Dance Festivals have been held every five years, typically drawing between 70,000 to 100,000 attendees (equivalent to about 7% of Estonia’s entire population). It also draws many foreign visitors and Estonian expats living abroad.

Performers also number in the thousands, including dozens of groups from abroad. There is a strict audition process and rehearsals begin months in advance. The closer you get to a festival, the more common it is to see Estonians on the streets in national costume as they travel to their rehearsals.

Although Estonians are known as relatively unexpressive in public, the Song and Dance Festival elicits strong emotions and it’s not uncommon to see attendees shedding a tear as tens of thousands join together in songs that led them through some of the darkest moments of their history. Estonian flags are flown, and many attendees wear traditional costumes even if they’re not part of a performance troupe.

The Estonian Song and Dance Festival is perhaps Estonia’s most important holiday. Held every five years, it is a massive and beloved expression of cultural and national identity.

Day of Restoration of Independence

In Estonian: Taasiseseisvumispäev

August 20, 2026

(day off: August 20, 2026)

This day marks the restoration of Estonian independence from the Soviet Union when the members of the Supreme Soviet of the Estonian SSR voted to secede from the USSR in 1991. The chairman of the Supreme Soviet who signed the resolution for independence, Arnold Rüütel, later became Estonia’s second president in 2001.

The day is marked by flag raising ceremonies, concerts, and other festivities that mark the continuity of Estonia’s independence which began in 1918 but was interrupted by the Soviet occupation. Most Estonians spend the day off with friends or out in nature enjoying their country.

Night of Ancient Lights

In Estonian: Muinastulede öö

Last Saturday of August

(Not a day off)

This tradition is a revival of the ancient coastal bonfires once lit to guide sailors along the Baltic Sea. Reintroduced in the 1990s, it is now celebrated all along Estonia’s coast and in neighboring countries. The fires are often accompanied by traditional music, singing, storytelling, and food and drink. Some cultural groups have formalized the event with concerts and public gatherings.

Participation varies by proximity to and whether one has ties to coastal areas. In recent years, the night has also become a time to remember Estonians who fled by sea during World War II as the USSR advanced towards them.

Resistance Day

In Estonian: Vastupanuvõitluse päev

September 22, 2026

(Not a day off)

This day marks the beginning of the Soviet reoccupation in 1944, at the beginning of Estonian resistance to that occupation. In the four-day gap between the Nazi withdrawal and Soviet arrival in 1944, Estonia briefly reestablished its constitutional government to assert its independence. The Soviets dismantled this government upon arrival, but resistance continued in many forms—from preserving culture and national identity at home to partisan fighters active in Estonia’s forests for three decades.

Resistance Day is marked by flag-raising ceremonies, concerts, and spending the day with friends and family, preferably outdoors, weather permitting. Since the start of the war in Ukraine, expressions of solidarity with Ukrainians and recognition of their ongoing resistance have become a common part of the day’s official observances.

All Souls’ Day

In Estonian: Hingedepäev

November 2, 2026

(Not a day off)

All Souls’ Day is celebrated in many countries as a day to remember the dead. It has roots in the agricultural cycle, coming just after the harvest and at the onset of winter. The ancient Estonians, and many other cultures, believed that at this time the worlds of the living and the dead drew close together, so close that dead relatives could come home to visit. This would be celebrated by laying out meals for the dead and preparing the sauna for them. It was believed that by doing so, the relatives and other spirits would help protect the crops and livestock.

Nowadays it’s far more common for a family to gather to share a trip to the sauna and a meal together, and then light a candle in memory of loved ones who have passed.

Martinmas and St. Catherine’s Day

In Estonian: Mardipäev and Kadripäev

November 10 and November 25, 2026

(Not days off)

Martinmas and St. Catherine’s Day, on November 10 and 25, are paired holidays that have rituals similar to trick-or-treating.

Martinmas is the Estonian Mardigras. Boys dress up in dark costumes and masks, going door-to-door in the evening making lots of noise, singing songs, and asking riddles. They often travel in groups led by a “father,” an adult male also in costume. Their arrival blesses the crops.

This is repeated for St. Catherine’s Day, when women and girls, dressed in white costumes, and led by a costumed “mother,” do the same thing. Their arrival blesses the livestock.

While the children do not ask for treats, those who welcome them will give out kohuke (a treat made of sweetened cottage cheese), chocolate, or similar snacks.

There are extensive folk traditions and tales, especially in rural areas, associated with the two holidays, many of which revolve around what brings health and prosperity versus bad luck.

Christmas Eve, Christmas, Second Christmas

In Estonian: Jõululaupäev, esimene jõulupüha, teine jõulupüha

December 24 – December 26, 2025

(days off: December 24 – 26)

Christmas is widely celebrated in Estonia, blending pre-Christian, Christian, German, Russian, and local traditions. The Estonian word jõulud comes from the old Scandinavian jul (perhaps related to the English yule) and carries no religious meaning – it remains closely tied to the winter solstice and the year’s darkest days. Around Christmas, the sun rises near 9 a.m. and sets just after 3 p.m. Traditionally, the season was meant to help the sun regain strength for the coming agricultural cycle, with ancient celebrations lasting from late December into early January.

Modern celebrations include following themed Advent calendars, like a tradition borrowed from the German, which are widely available in stores throughout Estonia. Town centers host festive Christmas markets with ice skating rinks, food vendors, and warm drinks like glögi (mulled wine). Schools and churches put on concerts that feature everything from traditional Estonian jingles, to translated Christmas classics, to original, modern Estonian holiday compositions.

Straw is a key holiday symbol. In Christian times it was linked to Christ’s manger, but in older traditions, it was used for cleaning and purification before the winter feast. Today, it’s crafted into elaborate decorative crowns and ornaments.

Estonians celebrate Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, and Second Christmas (December 26), with Christmas Eve being the most festive. Homes are decorated with spruce or fir trees, and families gather for a large meal before welcoming Jõuluvana (“Old Christmas”), the Estonian Santa Claus for whom songs are sung or poems recited before he presents the gifts.

Holiday menus vary, but common Christmas Eve dishes include roast pork, goose, and/or duck, sauerkraut, blood sausage, lingonberry jam, pickled pumpkin, cabbage, herring, jellied meat, and potatoes. Tangerines, apples, and nuts are popular snacks, and gingerbread is the season’s signature sweet—widely sold by late November, though many families bake their own.

December 25 is for relaxing and enjoying leftovers, while the 26th is often spent with extended family. Some Estonians visit graves of loved ones, lighting candles—a tradition that gained popularity during the Soviet era when Christmas was banned.

Estonia’s ethnic Russian minority celebrates according to the Julian calendar, with Christmas typically a quiet and religious-oriented night marked by church service and perhaps a family dinner. However, Orthodox Christmas is not an official holiday in Estonia.

You’ll Also Love

Estonian Holidays 2026: A Complete Cultural Guide

Estonia’s calendar is filled with holidays that make for an excellent introduction to its history, culture, and national values. Many, many holidays and observances mark Estonia’s struggle for independence, including the dates of key battles, declarations, and treaties. This is unsurprising for a nation that has enjoyed only a few decades of independence since the […]

Latvia’s Story of Identity: Paganism, Heroes, and Song

What shapes Latvian national identity? The answer is complex and personal, but one key element is the Latvian national narrative. This includes the heroes and pivotal events taught in schools, the places central to the nation’s collective memory, and the language and beliefs that frame its worldview. A national narrative goes beyond history: it is […]

Latvian Rye Bread Desserts: Rupjmaizes Kārtojums and Rupjmaizes Zupa

Rye has been grown in Latvia for more than 1200 years and rye bread (rudzu maize or rupjmaize) has been a staple of Latvian cuisine for nearly as long. The reason why is simple: rye grows well in moist soil and can be planted in spring and fall and is thus exceptionally well adapted to […]

Jewish Latvia: A Brief History and Guide

This guide offers advice to Jewish students considering study abroad programs in Latvia. Here, you’ll read about the local Jewish history, Latvia’s active synagogues, staying kosher, and about some of Riga’s major Jewish cultural organizations, museums, and memorials. Most importantly, we’ll get you on your way to engaging with the local Jewish community and comfortably […]

The Talking Latvian Phrasebook

The Talking Phrasebook Series presents useful phrases and words in side-by-side translation and with audio files specifically geared to help students work on listening skills and pronunciation. Below, you will find several useful phrases and words. To the left is the English and to the far right is the Latvian translation. In the center column […]