The following bilingual Russian MiniLesson is meant to build your vocabulary by providing Russian phrases within English text. Hover over the bold Russian to reveal its English translation.

To understand a culture’s folklore is to understand its roots. Folklore gives a glimpse into how the early participants of a culture saw the world around them and how they analyzed the problems and opportunities inherent in that world. While understanding a culture’s roots does not give a full picture of what form that culture might flower into, it does give a very good idea of where the culture came from and the basic building blocks that were used in constructing its current state.

Russian mythology and paganism differs strongly in many ways from its western analogues.

The earliest known history of Russia, The Primary Chronicle (ca. 1113) states that in Kiev, the Grand Prince constructed giant statues to several deities in the 10th century:

The list provided by the Chronicle is far from complete. Aside from the above, we can also find a deity called mentioned in a handful of sources. And in addition to that, the Ancient Russian lords swore oaths not only by the name of Perun, but also by the one of .

Early Orthodox sermons make constant admonitions against worshiping . As with many Slavic gods, there is some debate whether these were truly gods or regarded simply as natural or supernatural forces to align oneself with. Both were associated with one’s ancestors (their names literally translate to “Kin” and “Birth-giver”). They had .

A similar debate about god vs. natural force revolves around the goddess Мокош, mentioned earlier. . Some of these argue that the Slavs were in fact recognizing the power of having the right amount of moisture in the soil, but not necessarily worshiping an actual personality. Some argue that the evolution of a personality perhaps happened only later and only in some areas.

Some folklorists call this tendency to focus on keeping in harmony with natural (and supernatural) forces “lower mythology.” Its importance has been disparaged by some including scholar E. Anichkov, who said that Russian paganism was “particularly impoverished; its gods were pitiful, its cult and customs crude.”

However, it does not seem to have been so much crude as just very decentralized and complex. In Russian paganism, capricious spirits rule the world. For example, the . The rules of the домовой were many and complex. For example, if a peasant moved to a new house and did not properly invite his domovoi along, the displaced spirit would become angry, sometimes . Another story tells of a woman whose domovoi would braid her hair at night and forbid her to undo the braid. The woman lived 35 years without washing or combing her hair. When she finally did, just before her wedding day, her mother came home to find her chocked to death. The domovoi was blamed.

Similar spirits were plentiful. . They were also everywhere and unavoidable:

. The noise was said to disturb and attract spirits.

.

This cautious mentality is not at all surprising. In Russia the growing season is very short and any derivation in the crop cycle can result in or even . Early Russian history was also marked by almost constant warfare; meaning that dealing with was also a relatively frequent problem.

The Slavic pagan calendar was also complex. Elaborate rituals were common and usually concerned with agriculture. Holidays were held to mark, for example:

- ,

- ,

- ,

- .

The coming spring was celebrated before it even arrived, with Maslenitsa. This holiday is still celebrated with surprizing intensity throughout most Slavic lands. Round pancakes are feasted on in honor of the sun and games, festivals, family visits, and more held throughout a full week of celebration. Read more about Maslenitsa on our site here.

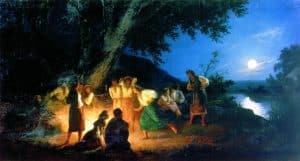

The summer solstice was also important to many pagan cultures, as it marks the day when summer is at its height and the days will now begin shorten and descend into winter. In the Slavic traditions, the celebrations were known as “” or ““.

Some have argued that Купала was a god of vegetation. Others argue that the name simply refers to the event. In Russian, купаться means “to bathe” and ritual bathing is a major part of the holiday observances. On this day, it was believed, the sun imbues the water with special, health-giving powers. Some myths explained this by saying that, on this day, .

On this day, straw effigies in order to ensure the upcoming harvest would be successful. Fire also marked a of the holiday: couples would jump over bonfires and if they remained holding hands when they landed, they would soon marry. Single people would jump hoping for luck.

. This was despite the constant reprimands of the Church but also in part due to the Church’s own actions. For example, the church attempted to replace Kupala with a holiday that honored John the Baptist. This only strengthened the that the peasants had already given John – or, translated loosely, “John the Bather.” The straw man used in the pagan ritual is to this day known as “Ivan Kupalo.” Kupala is still celebrated much as it always has been across most Slavic lands. Celebrations are almost always rural, though, and while news reports can be seen of them, the celebrations do not generally enter major cities.

This intricate interweaving of faiths is characteristic of Russian folk belief and is termed .

. For example:

- In 2002, Herbal Essences shampoos released a “” shampoo that was marketed in Ukraine and Russia.

- In 2004, a Russian travel agency advertised a package for romantic travel asserting that “” and offered a two-day, one night package of travel to the countryside for the holiday

- A Ukrainian horror film called , was produced based on a story by Gogol.

and are even enjoying the official support of regional and national governments and brand-name products. They are also, because of Russia’s isolation from such intellectual upheavals as the Renaissance and Reformation, as well as the isolation of individual villages from the central control of the church, still strikingly pure in their symbolism and society’s knowledge of where the traditions come from and what they mean.