The following bilingual Russian MiniLesson is meant to build your vocabulary by providing Russian phrases within English text. Hover over the bold Russian to reveal its English translation.

has always played an important part in Russian culture.

Since ancient times, Russians have said that . The баня was also thought in previous times to be highly medicinal for nearly ailments. Russians once said that . While today it is not usually recommended for sick people, the баня is still regarded as a powerful way to maintain one’s health and keep one’s spirits up.

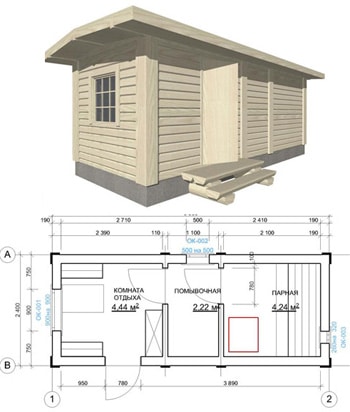

A traditional баня, whether private or public, will consist of several parts. The предбанник, which literally translates to “before the banya” is a dressing room for stripping down before entering the chamber. There is also a washing room or space called or sometimes even just . Sometimes the предбанник and помывочная are in a single room with the , where one takes breaks from the high heat and humidity, socializes over drinks and snacks. Sometimes all three rooms are separate compartments.

The main part of the баня is, of course, the heat chamber which is called the “парная” or “парилка”. Both derive their names from the Russian word .

Most frequently, the level of is manually regulated by pouring water on stones which are traditionally . The Russian баня is known as one of the most extreme of the world’s heat baths, with temperatures that range from 150-200F and humidity often approaching 80%. Most saunas in America, for instance, very rarely exceed 150F and 25% humidity. Russians by pouring water on the stones often and in small amounts, which allows this even, high steam to coat the room. They call this . Just be careful while pouring, as the stones are heated to well over 1300F!

In Russian баня culture, it is customary to say “с легким паром!” to those who have just returned from the баня. This literally translates to “with soft steam!” and means, loosely, “I hope you enjoyed the banya!” The phrase is perhaps best known as the subtitle of the classic Russian film , about a man who gets drunk at his traditional new year баня celebration and ends up going home to the wrong apartment in the wrong city.

To allow the body to sweat freely, the баня is typically used in the nude. While there are sometimes male and female compartments (or sessions), the баня is often coed. Modest people can cover up with a and in fact, most commercial баня facilities recommend that you wear a простыня for sanitary reasons. Other common supplies to take to the banya include , , to hold the веники, which are bunches of small, leafy birch or oak branches tied together.

The process begins by simply sitting in the баня and . After about seven minutes, one should exit to the комната отдыха, rest, and preferably drink water. On the second , the truly Russian tradition of begins, but to be truly effective, the sweating process should be well underway. This “massage” helps lift impurities from the skin and adds a pleasant fragrance to the person and room.

can be numerous and a visit to the can often last several hours. Заходы are interspersed with sessions of or or even Russians believe that these sudden shifts in temperature improve circulation and cause the body to release endorphins that improve the functioning of nearly all organs.

Russians are known for making their experience extreme, with long followed by snacking on pickles, vodka, and beer in the sessions of . However, all of these products are dehydrating and ill-advised. If you ever feel light headed or ill in the баня, excuse yourself and leave, explaining if needed that .

While a visit to the баня can leave one feeling refreshed and invigorated, there are obviously health risks as well. Such sudden shifts in temperature can be , as can prolonged exposure to high temperatures. Заходы should be kept to under 15-20 minutes. should last at least 15-20 minutes. is prohibited before entering the for the first заход, as a wet head can heat too quickly, causing stress to the brain.

One should not earlier than 1-2 hours after having meal but also not an empty stomach. Drink often and stick to water or at least juice and . Soda and strong tea are also not preferable in the баня. For food, stick to sausage, cheese, and bread and avoid the salt.

A баня session is usually ended with . There is a tradition of The head should be washed in one washbasin, the body in another, and a third is used for . However, many modern Russians will just shower or take one last plunge in the cold water.

Also, one should not after leaving the парная. Stroll around for several minutes first to allow your circulation to come back down to equilibrium.

Given these health issues, and given that the баня is usually a small wooden structure where a fire is kept and alcohol often consumed, it is not surprising that the баня figures in some of Russia’s most horrific mythology.

While Russians believed in the , and generally associated it health with purity, it was also inhabited by the who was perhaps the most fickle and easily offended of all the spirits that Russians once believed in.

To gain the favor of the банник, Russians would sacrifice a black hen to it after constructing the баня and before using it the first time. The hen was suffocated and buried under the entrance. While Russians typically wear crosses, many would remove them before entering the баня as it was thought that the holy object would upset the evil spirit. Water intended for the баня should not be drunk. Loud, sudden noises should be avoided and cursing is not allowed in the баня, as is thought that any damnation pronounced in the баня will come true and often come true sooner rather than later.

Guests were also supposed to be treated with great respect at the баня. The guest should enter first, be given plenty of food and drink, and offered a bed and rest after the session. Not abiding by rules of hospitality would offend not only the guest – but possibly the банник as well. Those who upset the банник were often maimed or killed by this powerful spirit.

While safety should be remembered at all times when using the баня, it can be an invigorating, healthy experience and a great taste of Russian culture. If you’ll be in Moscow, treat yourself to a trip to the Sanduni Banya, an 18th century palace of a banya complex that catered to (and still caters to) Moscow’s business elite. They also have pictures on the wall of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, John Travolta, and Scotty Pippen using their facilities. However, they have facilities within the price range of even students if you go as a group. Of course, many will tell you that you should go to a “real banya” – one in the country with a river or pond to jump into outside – there are also commercial opportunities to do this, but again, it’s best to go as a group, and best to have a Russian guide you. So ask around, make some friends in Russia, and go do it!